In this seminal piece, John W. Ellis explores the practice of Christian informal education, and contrasts it with formal approaches.

contents: introduction · traditional models · Jesus as an informal educator · youth clubs and youth work · informal and formal education · blending the two · conclusion · return to main contents

Introduction

[page 89] ‘Can you imagine St Paul being involved with anything like this?’ This question came from an ardent Christian as she surveyed our Youth Centre in full swing one evening. To be honest I had to admit I could not. I had a brief mental picture of the great Apostle gathering up his robes the better to line up the cue ball for a shot. But then I could not imagine St Paul climbing into his Ford Escort or dropping in at the local chip shop. It is simply not possible to make that sort of transfer across the centuries. The question had been put in a silly way. The questioner thought that it would highlight the inappropriateness, in Christian terms, of what she saw. Her question, however, had the unfortunate effect of deflecting any serious discussion of the issues involved. Nevertheless these issues need to be addressed.

In the first place there is an assumption that the churches’ primary task is educational. Christians are in the business of passing on to others the content of their faith. This assumption is accepted, while at the same time it is recognized that there are Christians who do not see the churches’ primary task in these terms.

In the second place there is a question. In what way, if at all, does a youth centre contribute to this primary task? It was her inability to see anything ‘educational’ happening that led to my friend’s rather odd question. She went on to ask whether we had an epilogue — a part of the proceedings when members were given a talk on some aspect of the Christian faith. When I confessed that we did not, I felt myself consigned to the ranks of well intentioned but misguided.

It is this question that we must now explore in some detail. My friend can be forgiven her unease about the whole operation; many who do not share her Christian presuppositions would have equal difficulty in seeing a youth centre’s work in educational terms. [page 90] Youth centres are usually seen by the public at large as a means of containment or social control; it ‘keeps them off the streets’. Youth workers loathe this phrase — it devalues what they are doing. But, to be fair, they are not entirely without blame for this popular misconception. They have been less than clear about what they mean when they talk about the educational value of youth work. Practitioners frequently discuss their aims in such all-embracing, grandiose terms that it is possible to justify almost any activity within their scope. This is the kind of self-delusion which does not inspire confidence.

Having said this, it has to be recognized that even if the work of the youth centre could be demonstrated to have educational value in terms of social development, this still would not satisfy my friend. She would, indeed, have seen this as cause for further unease. Not only was the primary task of the church not being tackled but scarce resources were being drawn into a secondary one. For Christians committed to informal education this is the crux of the problem. They find themselves under threat from two directions. On the one hand they suffer with their secular colleagues from the misconceptions of the public at large. On the other hand they come under attack from other Christians who see them as avoiding and even detracting from the churches’ primary task. It is this double-edged pressure which has led to the withering away of much Christian informal education. Secular youth workers find it difficult enough to justify their approach in terms of measurable effect. It has to be admitted that Christian informal education has apparently been singularly ineffective in carrying out the churches’ primary task.

Traditional models

The model of the Christian educator has long been that of the up—front preacher/evangelist who lays it on the line. Right across the board in the modern Christian community it is assumed that education means formal education. Anything else is viewed with misgiving and frequently rejected by ‘the person in the pew’ as a waste of scarce resources — to the chagrin of those within the church whose vision of education is wider. Christian formal education has moved on from the days of ‘chalk and talk’. It is often imaginative, makes use of the latest educational approaches and can be extremely effective in producing a well-informed committed Christian community. This very sophistication further threatens the informal, particularly at a time when resources — finance and personnel — are becoming increasingly scarce. There was a great blossoming of informal education in the form of Christian youth clubs in the 1960s. This is fast withering away. Most Christian youth centres are born [page 91] and die in an atmosphere of hostility and suspicion. They survive in spite of, rather than because of, the local Christian community.

Secular colleagues need to take warning. In the present climate they too could find themselves under threat from more thought-out educational approaches. Unless we are all prepared to produce a well-argued justification for informal education we will not survive. Above all, this justification needs to point to measurable results. All-embracing vagueness will simply no longer do. If this is difficult for the secular educator, it is infinitely more complex for Christians. For not only must Christian workers have clear educational aims to meet the requirements of a secular society where resources are dwindling but they must also be able to demonstrate that informal education is an appropriate vehicle for communicating the Christian message. If the first task is difficult the second appears to be beyond the reach of our present thinking.

Jesus as an informal educator

Oddly enough the starting point for this revolution lies in the work of Jesus himself as portrayed in the gospels. It could be argued that he was an early practitioner of informal education. There is a danger in this sort of approach. The life of Jesus is so potent and pregnant with meaning that groups as diverse as Marxists and right-wing fundamentalists have been happy to claim him for themselves. Having said this the fact remains that Jesus used the principles now enshrined in informal education to great effect. He gathered around him a large informal group of men and women ranging from the famous twelve Apostles to a wide variety of more or less interested ‘followers’. He drew these people into a shared experience that challenged their values. His teaching was largely informal — like his fascinating use of parable. These apparently simple folk tales have defied analysis in academic terms. In them Jesus threw the responsibility for learning back into the control of his hearers: ‘Those who have ears to hear let them hear’. Even his more formal teaching had an enigmatic quality which has bewildered those seeking formal concepts and thought-out philosophies. Again, the effect of this is to leave control in the hands of the hearers, who are challenged to rethink their values systems and to begin to develop a radical alternative life style. Hardly any of Jesus’ teaching was devoted to organization; the whole movement was left flexible and informal — still a cause of anguish within the church. This had a startling and dramatic consequence which was apparently quite intentional. The marginalized people or society were drawn right into the heart of the movement. Conversely the experts, those whose formal education gave them access to institutions of religion [page 92] and state, found themselves pushed to the fringe, unable to understand.

Here we confront the central issue which the challenge of informal education sets before the Christian community. Those who find themselves denied access to power in society develop for themselves a whole informal framework in which they operate with great skill and effectiveness. They value little the much vaunted fruits of formal education because they understand instinctively that the whole system is designed to deny them access to the power structures. It is this aspect of informal education which has received scant attention. The method you use to educate determines the client group with which you work. The further you move into the realms of formal education the more ‘up market’ your client group becomes. This is inevitable and inescapable. Therefore your choice of method in education actually reveals your value system. It reveals who you believe to be a priority group. I have heard Christian workers boast of the way in which their youth work became more effective in terms of the churches’ primary task when they shut down their youth club and moved to a more formal approach. ‘We were just wasting our time — now we see results for our labours.’ This sounds all very fine until it is understood that they not only shut the youth club, but also excluded from their work most of the members. Their work became ‘more effective’ because they moved to working with a client group who could appreciate a formal educational approach.

Youth clubs, youth work and the ‘upside down kingdom’

The much maligned youth club is still the only effective method yet devised to reach the marginalized young people of our society. Every step taken down the road that leads from informal to formal leaves behind increasing numbers of these young people. That is why all the sophisticated talk in youth work today which leads away from basic grass roots informal education must be resisted. The Youth Service, for all its faults, is all some of these youngsters have. It is the only setting in which they can learn in a way which is appropriate to them.

In the Christian context we are further constrained because we claim to be disciples of Jesus. I have already suggested that his use of the informal drew into the centre of his work the marginalized, powerless groups of his day. This was, I believe, no accident but a clearly thought out, premeditated strategy, an integral part of his teaching about the Kingdom of God. At the very heart of his message lay this concept of the kingdom or rule of God. He taught that one day this kingdom would supersede all other rule and all other authority. For now it was anticipated in his work and was to be [page 93] anticipated in the life of his followers. They were to live out God’s tomorrow — today! The kingdom Jesus described has been aptly described as the ‘upside-down kingdom’. In the kingdom of God the accepted value systems of this present age are turned on their head. What is highly valued in one is nonsense in the other. The people considered most important in one are considered to be of the least importance in the other. In his ministry Jesus demonstrated what it would be like when God was in charge. He deliberately chose methods of communication which empowered and gave value to those who were considered outcasts. In the closing hours of his life he was to come face to face with those who ‘really mattered’. To their utter amazement he was to remain almost totally silent in their presence. That silence was the most eloquent indictment of their whole value system.

It follows from this that those who today claim to be his followers need to live out the principles of the ‘upside-down’ kingdom. They need to prioritize time, effort and resources for those whom this society sends to the back of the queue. And because informal education appears to be the best tool we have yet devised to accomplish this, our commitment to it must not be allowed to falter.

Having said all this we must not delude ourselves. Those who advocate the use of informal education in the Christian context must be honest enough to admit that it appears to have been largely ineffective in terms of the churches’ primary task. Again, this problem is paralleled in the secular field. Secular informal educators have the greatest difficulty in describing, in terms that can actually be measured, what it is they are achieving in such a way as to convince their critics. We all take refuge at this point in vagueness. We are achieving a lot — the problem is just to quantify it. We may point to the progress some person has made towards self-fulfillment, but who is to say that that progress would not have been made anyway with time? Inexorably, we feel ourselves, in youth work terms, being pushed into the ‘keep them off the streets’ syndrome. Christian youth workers are even more at risk. Where the advocates of formal Christian education can point to positive results in terms of Christian young people — committed, informed and aware, we can only point to an occasional flicker of light here and there quickly extinguished by the cold water of peer pressure. And so we have got a problem and we need to admit that. I do not believe there is one Christian youth worker who has not wondered whether all this informal education is not a waste of time and effort. Many have given up under the pressure of external hostility and internal doubts. Those [page 94] who have survived have done so only because they are convinced that this approach is the only one capable of serving the young people with whom they are in contact. They know that to give up their commitment to informal education is to relinquish their commitment to the most needy young people in society. They are not prepared to do this and therefore they hang on with a sort of grim determination, hoping against hope for some kind of breakthrough.

In broad terms this is the present state of the art in Christian informal education: the determination of a dwindling band of youth workers to keep faith with a commitment. However, to remain in this ideological no man’s land would be to invite disaster. Eventually Christian informal education would just be a thing of the past, swamped by a confident and successful formal approach which was blind to its elitist tendencies. It is essential that we press forward in our thinking, that we ask hard questions about the apparent failure of the informal approach in terms of the churches’ primary task: that we formulate new initiatives for the future.

Informal and formal education

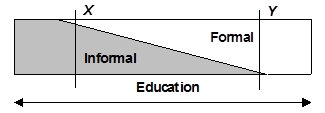

We have been speaking of formal and informal education as separate entities. Of course they are not; they are rather a continuum shading gradually into one another. Standing at either A or B and viewing the other side can be enlightening. The teacher standing at point B, committed to highly structured formal compulsory education, is aware that this approach is inappropriate, and in some cases, positively damaging to pupils, particularly those who are ‘least able’ in academic terms. The formal approach denies them a sense of personal worth and continually reinforces a negative self-image by persistently presenting them with evidence of their inability to cope. Many teachers are aware that the skills and attitudes developed in informal education are ideally suited to these young people. Many have initiated experiments in informal approaches. Whether these initiatives can survive in the present educational climate is a matter of conjecture.

Figure 7.1 Formal and informal education.

On the other hand the informal educators who find themselves at point A are aware of the strengths of the formal approach. They find {page 95] their efforts continually misunderstood and what little progress they make swept away by the combined forces of peer pressure and cultural norms. They have an urge to say loud and clear ‘that is not what I meant . . .‘ They long to be able to motivate and mould attitudes in the way they perceive possible in the formal field.

In Christian informal education this urge to say something has often found overt expression in what is generally termed ‘the epilogue’. At some point in the programme, usually towards the end of the evening, members are gathered together and given a talk about some aspect of the Christian faith. To the secular youth worker this appears very strange — a total turn around in the whole ethos of the proceedings. However odd it may seem it is an attempt to overcome the basic weakness inherent in informal education: that it is continually prey to misunderstanding. Informal education is rather like watching a film without the soundtrack. Viewers are left making up their own minds as to what the story might be about. The simpler the plot the easier this task becomes. Shoot out at the OK Corral would be fairly self-explanatory with or without its soundtrack. But the more complex and subtle the plot the more difficult the task of interpretation becomes. A film based, for example, on a Jane Austen novel would be almost unintelligible without its soundtrack. So it is with informal education — it communicates high-profile, accessible concepts well. But when the message becomes more complex, communication is inclined to break down.

It is important to understand why this is so. Viewers base their interpretation of what they see on their already formulated world-view. The more the plot is at odds with that worldview, the more misunderstanding is likely to result. Viewers filter what they see through their own perspective on life; the message is annexed to their own worldview and its power to challenge and transform attitudes is severely weakened. This is why Christian informal education has been apparently ineffective in terms of the churches’ primary task. Workers have been trying to communicate a worldview which challenges that of their clients at almost every point. The young people have only their own worldview to help them interpret what is happening. Take an example. A young man breaks into the club and causes damage or steals. Despite this he is readmitted to the centre. The Christian staff team believe that this will communicate the concept of forgiveness. But nothing of the sort is communicated. The young person reinterprets the action in terms of his own worldview. According to this, he has simply been lucky enough to come across a bunch of suckers.

[page 96] There is no way that attitudes can be changed on this basis. The young person would find it difficult to survive with this Christian attitude within his own culture. It appears to be possible only in the sheltered, unreal world apparently inhabited by the staff of the centre. The film devoid of its soundtrack has failed to communicate its message. The Christian concept of forgiveness is a complex one. Our forgiveness of others is based on God’s forgiveness for us. This was made possible by the death of Jesus on the cross. Jesus took the decisions which led to his death ‘on the street’. It was a course of action that was deliberate and challenged every accepted attitude to power and status now and then. This radical message is watered down to the inexplicable behaviour of a gang of well meaning suckers!

It is because informal education is continually swallowed up by cultural norms that we find ourselves with so little to show for our endeavours. This is particularly true of the Christian informal educator. The work is both complex and radical — but this is also true for the secular informal educator. Our centres become fantasy worlds divorced from the harsh realities of life outside. We had hoped that they would be centres of learning and renewal. Clients pass through untouched — with most of their attitudes intact. The solution is obvious: the film needs a soundtrack. The question is, how is the soundtrack to be supplied? The answer in Christian youth clubs has been to provide an ‘epilogue’. But this is to insert a chunk of formal education into the informal. The club night runs its course and then we suddenly change gear. However imaginatively this is done eyes become glazed as minds go into neutral. Young people frequently interpret what is happening in the light of their only other similar experience — the RE lesson at school. When the response to the epilogue is less than encouraging it is concluded that these young people have ‘no interest in Christian things’. Soon the pressure is on to move away from the informal, i.e. close the club.

The difficulty all this exposes is simply expressed. We have been so inclined to see the formal and informal as separate entities that if we move away from one we rapidly find ourselves drawn into the other. We are caught between two magnets: if we break free from the field of one we find ourselves stuck on the other. But this insistence on either/or is our problem. There is another possibility of learning to operate in the area where the formal and informal shade into one another. This is the area indicated by XY in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2 Formal and informal education — x-y: the arena for intervention.

Blending the two

I am convinced that this subtle blend of the formal and the informal is the solution to our difficulties. But here we are on the [page 97] edge of largely unexplored territory. We are seeking to communicate the Christian message to some of the more alienated people in our society. Informal education is continually absorbed into their already formal perspectives, which are the fruit of much bitter experience. Formal education is just a complete turn off and can survive only when backed either by compulsion or some sort of bribe — ‘you can only come to club if you stay for and behave in the epilogue’. But if we could blend together the formal and informal so that they belonged together as naturally as film and soundtrack.

How might this be achieved? To the best of my knowledge this is largely unknown terrain in both the secular and Christian fields. We have all made expeditions into it. Sometimes they have been planned, though more often than not it has been a chance experience in the midst of the ordinary that has filled us with a sense of what might be. We have been unable to sustain the position. Old ideas have hauled us back into their secure grip. Pressure of time and fear of failure have added their deadly discouragement.

At this point I frequently find myself meditating on a story from the Old Testament. After much wandering the people of Israel had arrived in the wilderness at the very borders of the promised land. They sent spies to check things out. These men returned with glowing reports of a land flowing with milk and honey. However they also brought tales of insurmountable difficulties — walled cities and, would you believe — giants. Discouraged by these tales of woe the people turned back into the wilderness and a whole generation were to perish before they again stood on the borders of the good land. If we continue to draw back it could be equally disastrous for us. There are certainly plenty of prophets of doom who urge retreat with tales of the problems that lie ahead. But it is vital that we press on to explore this crucial area where formal and informal merge (XY).

Conclusion

But is this all that can be said —just a rousing call to arms? I do not [page 98] believe so. The other point of that Old Testament story is that the spies brought back actual evidence of what lay ahead. We are told that they carried back a bunch of grapes so large that it had to be carried on a pole between two bearers. We too have brought back fruits from our promised land, which could be evidence of good things to come. I should like to draw attention to three of these.

The first is participation. I almost hesitate to mention this. I can, indeed, hear the groans and yawns with which its mere mention will be greeted — the concept has become such a bandwagon. It appears to be seen as some kind of cure for all ills in areas such as the Youth Service, adult education and community work. Having said this, there is no doubt that work in the area XY where the formal and informal shade into one another will be essentially participatory. Unless our life together is truly a shared experience there are no channels along which ideas can flow. We need to ignore the unease we feel at jumping on the latest bandwagon. I am not talking about members and consultative committees and the like. These methods, with all their pseudo-political and pretentious paraphernalia are really firmly rooted in the formal elitist area of education. They create a false impression of participation but can be continually manipulated by those skilled in their operation. I am rather suggesting exploring non-elitist informal channels for discussion and decision making. These need to take on the cultural ethos of those participating in them. This starting point means asking how individuals go about making decisions and then going on to ask how these processes can be built into our work.

Secondly, I would suggest that the message we wish to convey needs to be explicit in the informal and formal alike. Otherwise the formal soundtrack will be out of synchronization with the informal experience. This may mean making some very hard decisions about our programmes. We need to identify what it is we wish to communicate and then look for those activities and experiences that put the message across. It is when this blend of medium and message have fortuitously come together that we have glimpsed the promised land. There is another aspect to all this. It is impossible to communicate a radical message to others unless you are prepared to live it out yourself. Christian informal educators are part of their own message. There is a little Christian jingle that goes, ‘What you are speaks so loud that the world cannot hear what you say’. If our faith is some kind of part time hobby, like golf or stamp collecting, it will certainly have little impact on those who have already formed their perspective on life through much hard-won experience.

[page 99} Thirdly, there is a whole range of activities that have within their very structure this blend of formal and informal. These need to be given a much higher profile within our work. Drama, art, music, simulation games — done unpretentiously — could all help us further along the road we wish to travel. These methods all engage the interest and attention of participants — the great strength of informal education. However, at the same time, the educator remains in control of the message being relayed — the strength of formal education. They therefore offer exactly the sort of subtle blend of formal and informal that we are seeking. We may feel inexperienced in these areas but this can facilitate learning together.

This, then, seems to me to be the present position in Christian informal education. To fail to recognize the weaknesses inherent in the approach would be to court disaster and would ultimately lead to a complete abandonment of informal education within the Christian community, at least, by those who saw the churches’ primary task as an educational one. But to abandon the informal in this way would be at the same time to abandon those people for whom the formal is totally inappropriate. To find the subtle blend of formal and informal suggested above is a difficult undertaking. It must now become our aim to work this out in practice.

It is worth remembering that though this territory is new and strange for us, it has not always been so within our own culture, nor is it so in many Christian communities worldwide. There is stored away in the Christian community a vast resource of experience in cross-cultural communication. This reaches back, as we have seen, to the methods used by Jesus himself. John begins one of his letters with these words:

We write to you about the Word of life which has existed from the very beginning. We have heard it, and we have seen it with our eyes; yes we have seen it and our hands have touched it.

This ‘hands—on’ experience of the Christian faith is what we must be determined to provide within our work, for nothing less will suffice for the people to whom we are committed.

© John W. Ellis 1990

Please note the section headings were added for this page. They were not in the original.

For details of references go to the bibliography

Return to Using Informal Education main page

Reproduced with permission from Tony Jeffs and Mark Smith (eds.) Using Informal Education, Buckingham: Open University Press.

First published in the informal education archives: February 2002.

updated: August 12, 2025