In this chapter taken from Leonard P. Barnett’s (1951) The Church Youth Club, some key debates and questions around the relationship of church youth club work and the wider Church are explored.

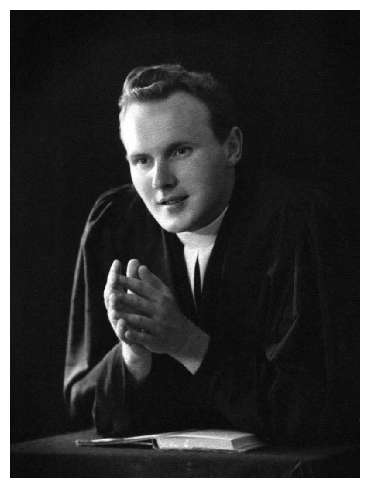

Leonard P. Barnett was a key figure in the development of youth work within the Methodist Church. He was National Secretary of the Methodist Association of Youth Clubs (between 1949 and 1958) – and wrote two particularly important and influential books: The Church Youth Club (1951) and Adventure with Youth (1953; 1962). were important and pioneering works.

See, also on infed.org: Leonard Barnett and the church youth club. Other pieces by Leonard Barnett in the archives include: responsible people; and why youth clubs?

[page 48] The church youth club must be seen as an out-working of the faith and practice of the local community of Christians. It is an expression of the Church’s awareness of its responsibility to care for all. Clearly the church club has its roots in the society from which it springs. In the vast number of cases, church clubs are controlled by officers deriving their function and mandate from the properly constituted church authorities. Those officers are either members or adherents of the church. The club itself usually meets (though not invariably) on the premises of the church concerned; and it should be looked on as just as essential a part of the family life of the local Christian community as say the Sunday School.

If indeed churches in general regarded their youth clubs in this way, then it is safe to say that some of the problems of club-church relationships which still beset not a few church club leaders would be well on the way to solution. There has yet to be made any complaint against the accepted principle that Sunday Schools exist to serve the needs of any boy or girl who cares to attend them. And yet in some quarters, one still hears it lamented that all and sundry young people may come into this church club and that. At the risk of irritating repetition, let it be said again simply that the church club being what it is a means of Christian education and evangelism – then the only valid criticism on this issue is that which might be launched against the ‘closed’ church club, which seeks as members only those who already have some active association with the church in question.

[page 49] There is little difficulty in getting church members to realize that a ‘closed’ church club has a rightful and legitimate place in the church community. The members are ‘our own young people’. But the more searching test of the true missionary spirit of many a Christian community has been the readiness or otherwise of its members to recognize that the unchurched youngsters who have crowded boisterously into its premises are part of the very constituency it was called into being to serve, and in the neglect of which the church loses its very raison d’etre. Out of that test, not a few churches have emerged with indifferent success.

It is surprising to realize that many otherwise informed people should still labour under the impression that the average church club today is ‘closed’ in the sense in which the term has been used. If that had indeed been so over the past few years, then the happenings to which the analysis bears its own witness would have been impossible. The young people would not have been there to respond to a Christian challenge. Out of one hundred and fifty clubs quoted later, only fourteen are limited in membership to ‘Methodist young people’. It may be hazarded that the analysis affords a fairly accurate index to the character of the majority of church clubs. This is a simple but highly significant fact. For too long it has been assumed that only non-attached clubs in the main could be classed as ‘open’ clubs. The 1947 Report, for instance, of a Commission appointed by the National Association of Boys’ Clubs to inquire into religion in clubs, simply equates ‘closed’ with ‘church’ clubs, and ‘open’ with ‘non-church’ clubs. The varying strengths of the links connecting church clubs to their local churches is recognized, but for all that the fact is ignored (one can hardly imagine it to have been unknown to the members of the Commission) that the average church club is fast becoming, if it is not already, an ‘open’ club.

[page 50] So far as M.A.Y.C. is concerned, where closed clubs are found it is almost invariably due to the fact either that accommodation shortage obliges a restriction of membership; or the church concerned already has associated with it as many young people with prior church affiliations as it can effectively handle.

But in the vast majority of clubs connected with M.A.Y.C., it is safe to say that the churches concerned did not begin club work with an abundance of church-associated youth. Clubs were deliberately begun in a large number of cases to attract into the church’s life and fellowship young people who had no such associations, or those of the vaguest kind.

That is not to say that the real aim and function of the church club, as it is sketched here, was generally clear and explicit from the early days of the movement. The situation, for instance, in the early war years hurried many churches into beginning youth work along club lines which were marked quite often by a simple desire to see that ‘something was done for the young people’. But the definition of that something remained in some cases sadly or exasperatingly blurred. The view has gained a deepening hold upon the minds of church youth club workers, however, that if church clubs are to provide recreation and nothing more, then although there may still be a case to be made out for them on grounds of social service, their true function is not being realized. The church club properly exists to provide informal but adequate Christian education – in short, to produce young Christians. This is our axe, and for it we have no apology. We are out to communicate for Christian faith in its fullness, believing that if we succeed we shall have helped ipso facto to facilitate the true development of personality, to promote good citizenship, and all the other wholesome, and laudable aims of the Youth Service.

Though this does not purport to be a book of Christian [page 51] apologetics, a reminder of the basic religious convictions from which the church club movement springs is very desirable.

Foremost of these is the belief that this is God’s world, and that it can only work satisfactorily God’s way. That way has been set forth in the life and work of His only Son our Saviour Jesus Christ. Inasmuch as folk, young or old, are willing to make the response of faith in God through Christ, stepping out to live life under His divine tutelage and discipline, they become truly free to rise to full dignity of their manhood and womanhood, and to discover their essential relationship to each other as members of God’s family. The response of faith is born of a sense of need, and awareness of being in a far country, and a ‘coming to oneself’. It involves penitence, forgiveness, and renewal; the deliberate denial of selfishness in order to begin discovering the true self. Then, and only then, begins the progression of the individual towards true maturity. Then, and only then, does he find adequate and objective standards for his behaviour, and a for ever appropriate clue to the unravelling of life’s tangled skeins. The Christian is a citizen of an enlarging Kingdom, the Realm of God, which is both personal and social, present and to come – a Kingdom in which peace and righteousness march hand in hand, and where the sicknesses in the soul of humanity have found their only ultimate remedy.

This, and more, do Christians believe. This is why the Gospel must remain for ever good news – of a unique kind. It spells liberation of the spirit, paradoxically enough through self-fulfilling discipline. It is a faith not only of the head but the heart, and involves the whole man in an acceptance of a ‘way of life’ marked by moral adventure worlds removed from the cheap and shoddy interpretation sometimes set upon the word. The Christian’s is a fighting creed, and to our shame it is that so [page 52] often it has become equated in the mind of youth with passivism and mediocrity, colourless inertia and blind unimagination. For those who have truly entered into an experience of the living Lord, to follow Him is the most highly personal crusade to which it is their high privilege to seek to summon others.

But it is more than this. The Christian is no moral Don Quixote. He must be a practical citizen soldier, schooled in the most essential art of united action in the interests of the Kingdom. Like education itself religion is at once intensely personal and inescapably social. It begins with a personal encounter. It proceeds to a common enterprise.

A most vital part of the Christian’s creed is his belief that just as he has entered into an experience of God’s Fatherhood, so must that experience lead to practical action in his attempts to build and strengthen a family community where all men shall truly be at home together. The present expression of that community is the Church, without which he himself would clearly have had no knowledge of the faith he has embraced. He is tragically conscious that the Church is in a real sense only ideally existent – that whichever section engages his loyalty is only a fragment of the mutilated Body; but that does not relieve him either from belief in the necessity of the Church or from the responsibility of contributing to its life and work.

He recognizes the Church as the most significant element in the strategy of the Kingdom. It is the bastion from which the Christian offensive is launched. Evil is itself strongly entrenched. Its very genius is often to intertwine with that which of itself is perfectly wholesome, either within the life of the individual or of society. To fight efficiently those sub-Christian elements in modern life generally termed ‘social evils’, demands a committed organized community. ‘Legions of wily fiends’ call for [page 53] battalions of opposition forces. The World Church represents those forces which not only provide the means to plan systematically the spread of the Gospel, but also afford the quite indispensable mutual support and encouragement to the individual Christian in his pilgrimage.

One cannot be a Christian in isolation. Neither the New Testament nor subsequent history knows anything of effective individual effort totally unrelated to the main forces of Christianity as represented by the Church. In war-time, even those specialists in individual warfare, the Commandos, were conceived from headquarters, trained by it, and were in all points directed in the interests of an over-all strategy. The same must always be true of the Christian. It is safe to assert that the most highly individualistic and sacrificial Christian service performed by anyone anywhere during the centuries of Christian history would have been quite impossible without the existence of the Church. If her adventurous sons have sometimes left home to do their yeoman service, only the shallow-minded are likely to forget the prime role of that home in the matter of preparation, equipment, and opportunity.

In other words, it must be crystal clear that Christian discipleship necessarily involves active association with the Christian community, the fellowship of those who are ‘being saved’. Not for one moment would we dismiss at all lightly the brave and challengingly high living of many who are not within the fold of the Church. But we must at all costs insist that such living is not, cannot, in the fullest sense, be termed ‘Christian’.

The Church, ideally, is the gift of God and the vehicle of His Holy Spirit. By the Church and no other agency will His purposes for the world ever be realized. Whilst I most emphatically believe that, it is not part of our purpose to argue here the doctrine of the Church. It is very much part of our purpose to insist that we must [page 54] look upon membership of the Church as an inalienable element in full Christian living. And it is full Christian living that church clubs invite their members to share.

Part of the corporate life of the Church is enjoyed in its family worship. And in the light of all that has been said, it is sincerely hoped that another nail will have been knocked into the coffin of one hardy annual produced regularly by church club critics and indeed from church club workers themselves. It really is surprising, from one point of view, that so many thoughtful voices should have joined in the chorus either of disapprobation or disavowal over the matter of club members’ attendance at public worship, and of membership of the Church. To list those who are on record as either saying they disapprove of clubs being an overt attempt to fill empty pews, or (from Christian club workers in church clubs) dissociating their work from the accusation, would of itself be an extremely tedious and futile procedure.

The right answer would surely seem to be to insist, in the first place, that quite obviously, if worship is a staple ingredient of the Christian diet, part of our total task is to fill pews, if they need filling, either with young people or older. The fact is, of course, that the kind of people who regard full churches as the sine qua non of virile Christianity, and cannot rid themselves of the idea that nothing matters so long as the church attendance figures are satisfactory, are – as far as one’s own personal observations are concerned – the last people one would normally expect to have either the time or talent for efficient church club work.

What, after all, is the real objection to trying by every legitimate means within our power to get young people to come to church? That we are using them as means to an end? That we are, in fact, not interested in them as people, but only as occupants of a space that needs occupying? To assert that would simply make nonsense of everything [page 55] that has so far been written above, and if any Christians have been guilty of a mental attitude of that description, It is pretty safe to say that they have discovered their error long since and repented, or else given up the attempt as a thoroughly bad job.

But what of those who deliberately set out, inter alia, to persuade club members by every legitimate means to worship with the rest of the local Christian community? Are they guilty of a wrong attitude? Surely not, provided the convictions stated above are not invalid.

Christians can never forget – or if they do, they are guilty of the gravest error of thought – that worship is one of the means of grace. Worship is one of the traditional techniques Christians have always used to develop efficiently the life of the soul. There is something terribly academic and chilling about the bare phrase, ‘church going’ – as if it were just one more corporate activity for those whose tastes run in that direction. Without launching into a dissertation of all that worship means to a normal, practising Christian, it is perhaps enough to suggest that regular worship, for him, is as necessary to his spiritual ascent as ropes and irons to a rock-climber.

If we are seeking to grow young Christians, then we must insist that no trace of an apologetic attitude for our enthusiasm over this matter of encouraging our members to worship is ever necessary. We should be withholding a privilege as well as becoming guilty of neglect if we skirted round this matter in our dealings with them.

Apart altogether from this issue, there ought to be a clear appreciation of the markedly advantageous position from which the church club worker begins his task, over against his colleagues in clubs unattached to any church or other adult Christian group. Both the N.A.B.C. and N.A.G.C. and M.C. (1) have as their avowed aim the spiritual well-being of their club members, and it is significant to note the concern that both associations have felt in recent years over the implementation of this aim in the life and practice of the local club. By far the greatest of the practical problems connected with the issue arise out of the fact that a large number of the clubs belonging to the associations are denied the vital help of a linked adult community. (2)

The church club worker can but recognize with deep thankfulness that he is in a favoured position. He is himself a member of the selfsame Christian community into whose family life he aims to introduce his members. His club probably meets on premises shared with that community. His club devotions may well be conducted in the church itself. Everything about them reminds the club members that they are within the pale of the church. At the very least, they sometimes see the minister in charge. He may be their leader, chairman, or chaplain. Best of all, he may be their friend, who respects them as persons, who rejoices to play as well as pray with them, and who is wiser than to be continually harrying them for the Gospel’s sake. He does not interlard the secular with an occasional spread of the spiritual. The one permeates the other. The focal point is worship that should be as natural as it should be dignified. This is an advantage compared to which the best premises, the most satisfactory budget sheet, the glossiest equipment, are all secondary. The aim of well-being, physical, mental, and spiritual, can find a real chance of fulfilment, without any violent and unneccessary transition, either physical or psychological. In Church a Family is a target to aim at which the church club stands at the best possible vantage point.

(1) See Principles and Aims of the Boys’ Club Movement (N.A.B.C.) and The Religious Interpretation of the Aims of the Association (N.A.G.C. and MC.)

(2) The Report of the N.A.B.C. Commission, to which reference has been made, is a highly valuable document for the study of this problem and should be read in conjunction with a most useful memorandum Spiritual Well-being in Boys’ Clubs (N.A.B.C. 1944.)

Reproduced from Leonard P. Barnett (1951) The Church Youth Club, London: Methodist Association of Youth Clubs. Available in the informal education archives. [https://infed.org/mobi/church-and-club/]

This piece has been reproduced here with permission. First placed in the archives: August 2002. Updated June 2019

Last Updated on June 20, 2019 by infed.org