Malcolm Knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogy. A champion of andragogy, self-direction in learning and informal adult education, Malcolm S. Knowles was a very influential figure in the adult education field. Here we review his life and achievements, and assess his contribution.

Malcolm Knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogy. A champion of andragogy, self-direction in learning and informal adult education, Malcolm S. Knowles was a very influential figure in the adult education field. Here we review his life and achievements, and assess his contribution.

contents: introduction · malcolm knowles – life · adult informal education · malcolm s. knowles on andragogy · self-direction · conclusion · further reading and references · links

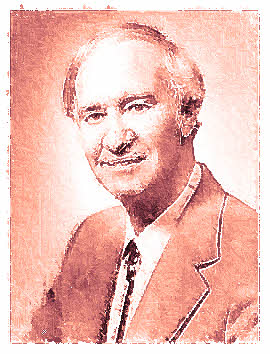

Malcolm Shepherd Knowles (1913 – 1997) was a, perhaps ‘the’, central figure in US adult education in the second half of the twentieth century. In the 1950s he was the Executive Director of the Adult Education Association of the United States of America. He wrote the first major accounts of informal adult education and the history of adult education in the United States. Furthermore, Malcolm Knowles’ attempts to develop a distinctive conceptual basis for adult education and learning via the notion of andragogy became very widely discussed and used. He also wrote popular works on self-direction and on groupwork (with his wife Hulda). His work was a significant factor in reorienting adult educators from ‘educating people’ to ‘helping them learn’ (Knowles 1950: 6). In this article we review and assess his intellectual contribution in this area with respect to the development of the notions of informal adult education, andragogy and self-direction.

Malcolm Knowles – a life

Born in 1913 and initially raised in Montana, Malcolm S. Knowles appears to have had a reasonably happy childhood. His father was a veterinarian and from around the age of four Knowles often accompanied him on his visits to farms and ranches.

While driving to and from these locations, we engaged in serious discussions about all sorts of subjects, such as the meaning of life, right and wrong, religion, politics, success, happiness and everything a growing child is curious about. I distinctly remember feeling like a companion rather than an inferior. My father often asked what I thought about before he said what he thought, and gave me the feeling that he respected my mind. (Knowles 1989: 2)

Malcolm Knowles has talked about his mother helping him through her example and care to be a more ‘tender, loving, caring person’ (op. cit.). His schooling also appears to have reinforced his ‘positive self-concept’. Boy scouting was also a significant place of formation: ‘the knowledge and skills I gained in the process of learning over fifty merit badges and performing a leadership role were as important in my development as everything I learned in my high school courses’ (ibid.: 4).

Malcolm Knowles gained a scholarship to Harvard and took courses in philosophy (where he was particularly influenced by the lecturing of Alfred North Whitehead), literature, history, political science, ethics and international law. Again, his extracurricular activities were particularly significant to him. He became President of the Harvard Liberal Club, general secretary of the New England Model League of Nations, and President of the Phillips Brooks House (Harvard’s social service agency). Involvement in voluntary service for the latter got him working in a boys club. Knowles also met his wife Hulda at Harvard. Her father was a tool-and-die maker in Detroit’s motor industry and an active unionist. ‘As we talked’, Knowles was later to write, ‘it became clear that our values systems were identical’ (ibid.: 29).

Initially intending to make a career in the Foreign Service, Malcolm Knowles enrolled in the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy when he graduated in 1934 from Harvard. He passed the Foreign Service exam – but there was a three year wait for entry. Hulda and he had got married in 1935 and he needed a job. Knowles joined the new National Youth Administration in Massachusetts. His job involved him in finding out what skills local employers were looking for, establishing courses to teach those skills, and recruiting young people to take the courses. About three months into the work he met Eduard Lindeman who was involved in the supervision of training within the NYA. Lindeman took Knowles under his wing and effectively became his mentor. Knowles read Lindeman’s Meaning of Adult Education: ‘I was so excited in reading it that I couldn’t put it down. It became my chief source of inspiration and ideas for a quarter of a century’ (Knowles 1989: 8).

In 1940 Malcolm Knowles was approached by Boston YMCA to see if he would be interested in becoming director of adult education and organizing an ‘Association School’ for adults. He was drafted into the Navy in 1943, began to read widely around the field of adult education, and decided to undertake a masters programme at the University of Chicago when he was mustered out. To support himself through the programme he got a job at the Central Chicago YMCA as director of adult education. His adviser at the University of Chicago was Cyril O. Houle whose ‘deep commitment to scholarship and his role in modeling a rigorous scholarly approach to learning’ were of great importance. Knowles also fell under the influence of Carl Rogers. Early in his master’s programme he had enrolled in a seminar in group counselling under Arthur Shedlin (an associate of Rogers). ‘It was exhilarating. I began to sense what it means to get “turned on” to learning. I began to think about what it means to be a facilitator of learning rather than a teacher’ (ibid.: 14).

Malcolm Knowles gained his MA in 1949. His thesis became the basis of his first book Informal Adult Education published in 1950 (see below). In 1951 he became executive director of the newly formed Adult Education Association of the USA. He attended a couple of summer sessions of the National Training Laboratories (in 1952 and 1954) and was influenced by the thinking of their founders: Kenneth Benne, Leland Bradford and Ronald Lippett – and of Kurt Lewin. Hulda and their children were also involved in the seminars – and one fruit of this, in part, was Malcolm and Hulda’s joint authorship of books on leadership (1955) and group dynamics (1959). Knowles spent nine years at the Adult Education Association, and as Jarvis (1987: 170) has commented, ‘he was able to influence the growth and direction of the organization’. He also started studying for a PhD (at the University of Chicago). Significantly, he began charting the development of the adult education movement in the United States – and this appeared in book form in 1962. It was the first major attempt to bring together the various threads of the movement – and while it was not a detailed historical study (Jarvis 1987: 171) it was the main source book for more than twenty years. As Jarvis (1987: 172) has commented:

He saw that the movement was, in a sense, peripheral to the dominant institutions in society and yet important to it. He recognized that the very disparate nature of the movement prevented its being adequately coordinated from a central position. [This] … free-market needs model of adult education provision … is a position he … maintained even after adult education became much more established and scholars were calling for a more centrally coordinated approach… [I]implicit within this position … is perhaps one of the central planks of his philosophy; that adult education must be free to respond to need, wherever it is discovered.

In 1959 Malcolm S. Knowles joined the staff at Boston University as an associate professor of adult education with tenure and set about launching a new graduate programme. He spent some 14 years there during which time he produced his key texts: The Modern Practice of Adult Education (1970) and The Adult Learner (1973). These books were to cement his position at the centre of adult education discourse in the United States and to popularize the notion of andragogy (see below). In 1974 he joined the faculty of the North Carolina State University where he was able to develop courses around ‘the andragogical model’ (Knowles 1989: 21). He also updated his key texts and published a new book on Self Directed Learning (1975).

Malcolm S. Knowles ‘retired’ in 1979 but continued to be deeply involved in various consultancies and in running workshops for various agencies (something he had begun much earlier in his career). He was also associated with North Carolina State University as Professor Emeritus. He had time to write further articles and books. Some nine years into his retirement he commented that he couldn’t imagine ‘a better, richer life’ (ibid.: 24). He died on Thanksgiving Day, 1997, suffering a stroke at his home in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Adult informal education

The notion of informal adult education had been around in the YMCA before Malcolm Knowles’ book was published in 1950. In Britain Josephine Macalister Brew had published the first full-length treatment of informal education in 1946. However Informal Adult Education was a significant addition to the literature. Knowles was searching for a ‘coherent and comprehensive theory of adult learning’ – and the closest he could come to an organizing theme was ‘informal’ (Knowles 1989: 76). Later he was to comment that while this was surely ‘an important component of adult learning theory… it was far from its core’ (op. cit.).

In focusing on the notion of informal education, Malcolm Knowles was pointing to the ‘friendly and informal climate’ in many adult learning situations, the flexibility of the process, the use of experience, and the enthusiasm and commitment of participants (including the teachers!). He didn’t define informal adult education – but uses the term to refer to the use of informal programmes and, to some extent, the learning gained from associational or club life. He commented that an organized course is usually a better instrument for ‘new learning of an intensive nature, while a club experience provides the best opportunity for practicing and refining the things learned’ (Knowles 1950: 125). Clubs are also ‘useful instruments for arousing interests’ (op. cit.). He contrasts formal and informal programmes as follows:

Formal programs are those sponsored for the most part by established educational institutions, such as universities, high schools, and trade schools. While many adults participate in the courses without working for credit, they are organized essentially for credit students… Informal classes, on the other hand, are generally fitted into more general programs of such organizations as the YMCA and YWCA, community centers, labor unions, industries and churches. (Knowles 1950: 23)

This distinction is reminiscent of that later employed by Coombs and others to distinguish formal from non-formal education.

Informal programmes, Malcolm S. Knowles suggests, are more likely to use group and forum approaches.

Several important differences are found between the interests in organized classes and the interests in lecture, forum and club programs. In the first place, the former are likely to be stable, long-term interests, while the latter are more transitory. In the second place, lectures, forums and club programs are more flexible than organized classes. In a program series the topics can range from pure entertainment to serious lectures, while an organized class is necessarily limited to a single subject-matter area. Third, the lecture, forum, and club types of programs generally require less commitment of time, money and energy from participants than do organized classes. As a result they are likely to attract people with somewhat less intense interest. (Knowles 1950: 24)

Malcolm Knowles was able to draw on material from various emerging areas of expertise. This included understandings gained from his time with Eduard Lindeman, Cyril O. Houle and others within the adult education field; his knowledge of community organization within and beyond the YMCA (and via the work of Arthur Dunham and others); a growing appreciation of the dynamics of personality and human development (via Carl Rogers and Arthur Sheldin); and an appreciation of groupwork and group dynamics (especially via those associated with the National Training Laboratories). He also had some insights into the relationship of adult education activities to democracy from his contact with Dorothy Hewlitt at the NYA (see Hewitt and Mather 1937).

Exhibit 1: Malcolm S. Knowles on informal adult education

The major problems of our age deal with human relations; the solutions can be found only in education. Skill in human relations is a skill that must be learned; it is learned in the home, in the school, in the church, on the job, and wherever people gather together in small groups.

This fact makes the task of every leader of adult groups real, specific, and clear: Every adult group, of whatever nature, must become a laboratory of democracy, a place where people may have the experience of learning to live co-operatively. Attitudes and opinions are formed primarily in the study groups, work groups, and play groups with which adults affiliate voluntarily. These groups are the foundation stones of our democracy. Their goals largely determine the goals of our society. Adult learning should produce at least these outcomes:

Adults should acquire a mature understanding of themselves. They should understand their needs, motivations, interests, capacities, and goals. They should be able to look at themselves objectively and maturely. They should accept themselves and respect themselves for what they are, while striving earnestly to become better.

Adults should develop an attitude of acceptance, love, and respect toward others. This is the attitude on which all human relations depend. Adults must learn to distinguish between people and ideas, and to challenge ideas without threatening people. Ideally, this attitude will go beyond acceptance, love, and respect, to empathy and the sincere desire to help others.

Adults should develop a dynamic attitude toward life. They should accept the fact of change and should think of themselves as always changing. They should acquire the habit of looking at every experience as an opportunity to learn and should become skillful in learning from it.

Adults should learn to react to the causes, not the symptoms, of behavior. Solutions to problems lie in their causes, not in their symptoms. We have learned to apply this lesson in the physical world, but have yet to learn to apply it in human relations.

Adults should acquire the skills necessary to achieve the potentials of their personalities. Every person has capacities that, if realized, will contribute to the well-being of himself and of society. To achieve these potentials requires skills of many kinds—vocational, social, recreational, civic, artistic, and the like. It should be a goal of education to give each individual those skills necessary for him to make full use of his capacities.

Adults should understand the essential values in the capital of human experience. They should be familiar with the heritage of knowledge, the great ideas, the great traditions, of the world in which they live. They should understand and respect the values that bind men together.

Adults should understand their society and should be skilful in directing social change. In a democracy the people participate in making decisions that affect the entire social order. It is imperative, therefore, that every factory worker, every salesman, every politician, every housewife, know enough about government, economics, international affairs, and other aspects of the social order to be able to take part in them intelligently.

The society of our age, as Robert Maynard Hutchins warns us, cannot wait for the next generation to solve its problems. Time is running out too fast. Our fate rests with the intelligence, skill, and goodwill of those who are now the citizen-rulers. The instrument by which their abilities as citizen-rulers can be improved is adult education. This is our problem. This is our challenge.

Malcolm S. Knowles (1950) Informal Adult Education, Chicago: Association Press, pages 9-10.

Malcolm Knowles saw that the quality of the experiences people members have in the government of their own groups ‘influences the skills and attitudes they will carry into governing their nation’ (ibid.: 124). However, this interest was in many respects secondary to the possibility of making ‘clubs, groups, and forums effective instruments of adult education’ (1950: 123). For all the talk of ‘laboratories of democracy’, he didn’t fully grasp the significance of association. This may, in part, derive from the limited extent to which he experienced adult education as a social movement. Earlier figures like Lindeman and Tawney were deeply involved in progressive politics and activities. It is difficult not to escape the conclusion that even at this stage Malcolm Knowles was more concerned with establishing the claims of adult education as a separate area of professional activity and with individual learning, than with fundamental social change.

Malcolm S. Knowles on andragogy

Knowles was convinced that adults learned differently to children – and that this provided the basis for a distinctive field of enquiry. His earlier work on informal adult education had highlighted some elements of process and setting. Similarly, his charting of the development of the adult education movement in the United States had helped him to come to some conclusions about the shape and direction of adult education. What he now needed to do was to bring together these elements. The mechanism he used was the notion of andragogy.

While the concept of andragogy had been in spasmodic usage since the 1830s it was Malcolm Knowles who popularized its usage for English language readers. For Knowles, andragogy was premised on at least four crucial assumptions about the characteristics of adult learners that are different from the assumptions about child learners on which traditional pedagogy is premised. A fifth was added later.

1. Self-concept: As a person matures his self concept moves from one of being a dependent personality toward one of being a self-directed human being

2. Experience: As a person matures he accumulates a growing reservoir of experience that becomes an increasing resource for learning.

3. Readiness to learn. As a person matures his readiness to learn becomes oriented increasingly to the developmental tasks of his social roles.

4. Orientation to learning. As a person matures his time perspective changes from one of postponed application of knowledge to immediacy of application, and accordingly his orientation toward learning shifts from one of subject-centeredness to one of problem centredness.

5. Motivation to learn: As a person matures the motivation to learn is internal (Knowles 1984:12).

Each of these assertions and the claims of difference between andragogy and pedagogy are the subject of considerable debate. Useful critiques of the notion can be found in Davenport (1993) Jarvis (1977a) Tennant (1996) (see below). Here I want to make some general comments about Malcolm Knowles’ approach. (The assumptions of the model and its overall usefulness are further explored in the article on andragogy).

First, as Merriam and Caffarella (1991: 249) have pointed out, Knowles’ conception of andragogy is an attempt to build a comprehensive theory (or model) of adult learning that is anchored in the characteristics of adult learners. Cross (1981: 248) also uses such perceived characteristics in a more limited attempt to offer a ‘framework for thinking about what and how adults learn’. Such approaches may be contrasted with those that focus on:

- an adult’s life situation;

- changes in consciousness (Merriam and Caffarella 1991).

Second, Malcolm Knowles makes extensive use of a model of relationships derived from humanistic clinical psychology – and, in particular, the qualities of good facilitation argued for by Carl Rogers. However, Knowles adds in other elements which owe a great deal to scientific curriculum making and behaviour modification (and are thus somewhat at odds with Rogers). These encourage the learner to identify needs, set objectives, enter learning contracts and so on. In other words, he uses ideas from psychologists working in two quite different and opposing traditions (the humanist and behavioural traditions). This means that there is a rather dodgy deficit model lurking around this model.

Third, it is not clear whether this is a theory or set of assumptions about learning, or a theory, or model of teaching (Hartree 1984). We can see something of this in relation to the way Malcolm Knowles defined andragogy as the art and science of helping adults learn as against pedagogy as the art and science of teaching children. There is an inconsistency here. Hartree (1984) then goes on to ask: has Knowles provided us with a theory or a set of guidelines for practice? The assumptions ‘can be read as descriptions of the adult learner… or as prescriptive statements about what the adult learner should be like’ (Hartree 1984 quoted in Merriam and Caffarella 1991: 250). This links with a point made by Tennant (1988) – there seems to be a failure to set and interrogate these ideas within a coherent and consistent conceptual framework. As Jarvis (1987b) comments, throughout his writings there is a propensity to list characteristics of a phenomenon without interrogating the literature of the arena (e.g. as in the case of andragogy) or looking through the lens of a coherent conceptual system. Undoubtedly Malcolm Knowles had a number of important insights, but because they are not tempered by thorough analysis, they were a hostage to fortune – they could be taken up in an ahistorical or atheoretical way.

Self-direction

In its broadest meaning, ‘self-directed learning‘ describes, according to Malcolm Knowles (1975: 18) a process:

… in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes.

Knowles puts forward three immediate reasons for self-directed learning. First he argues that there is convincing evidence that people who take the initiative in learning (proactive learners) learn more things, and learn better, than do people who sit at the feet of teachers passively waiting to be taught (reactive learners). ‘They enter into learning more purposefully and with greater motivation. They also tend to retain and make use of what they learn better and longer than do the reactive learners.’ (Knowles 1975: 14)

A second immediate reason is that self-directed learning is more in tune with our natural processes of psychological development. ‘An essential aspect of maturing is developing the ability to take increasing responsibility for our own lives – to become increasingly self-directed’ (Knowles 1975: 15).

A third immediate reason is that many of the new developments in education put a heavy responsibility on the learners to take a good deal of initiative in their own learning. ‘Students entering into these programs without having learned the skills of self-directed inquiry will experience anxiety, frustration , and often failure, and so will their teachers (Knowles 1975: 15).

To this may be added a long-term reason – because of rapid changes in our understanding is no longer realistic to define the purpose of education as transmitting what is known. The main purpose of education must now to be to develop the skills of inquiry (op cit).

Malcolm Knowles’ skill was then to put the idea of self direction into packaged forms of activity that could be taken by educators and learners. He popularized these through various books and courses. His five step model involved:

1. diagnosing learning needs.

2. formulating learning needs.

3. identifying human material resources for learning.

4. choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies.

5. evaluating learning outcomes.

As Merriam and Cafferella (1991: 46) comment, this means of conceptualizing the way we learn on our own is very similar to much of the literature on planning and carrying out instruction for adults in formal institutional settings. It is represented as a linear process. From what we know of the process of reflection this is an assumption that needs treating with some care. Indeed, as we will see, there is research that indicates that adults do not necessarily follow a defined set of steps – but are far more in the hands of chance and circumstance. Like Dewey’s conception of reflection an event or phenomenon triggers a learning project. This is often associated with a change in life circumstances (such as retirement, child care, death of a close relative and so on). The changed circumstance provides the opportunity for learning, the way this is approached is dictated by the circumstances. Learning then progresses as ‘the circumstances created in one episode become the circumstances for the next logical step’ (op. cit.). Self-directed learning thus, in this view, becomes possible, when certain things cluster together to form the stimulus and the opportunity for reflection and exploration.

However, once we begin to take into account the environment in which this occurs then significant concerns arise with Malcolm Knowles’ formulation. Spear and Mocker, and Spear (1984, 1988 quoted in Merriam and Caffarella 1991: 46-8) found that ‘self-directed learners, rather than pre-planning their learning projects, tend to select a course from limited alternatives which happen to occur in their environment and which tend to structure their learning projects’. This is of fundamental importance. It is in this light that Brookfield’s (1994) question is pertinent: ‘What are the essential characteristics of a critical, rather than technical, interpretation of self-directed learning?’ Two suggest themselves:

- self-direction as the continuous exercise by the learner of authentic control over all decisions having to do with learning, and

- self-direction as the ability to gain access to, and choose from, a full range of available and appropriate resources.

Both these conditions are, he argues, as much political as they are pedagogical and they place educators who choose to use self-directed approaches in the centre of political issues and dilemma.

There are also further problems with Malcolm Knowles’ approach that he shares with other writers. These include issues arising out of the use of ‘humanistic psychology’; questions around the notion of selfhood (and the cultural specificity involved); and the research base for explorations. These are reviewed in the article on self-direction).

Conclusion

Malcolm S. Knowles was responsible for a number of important ‘firsts’.. He was the first to chart the rise of the adult education movement in the United States; the first to develop a statement of informal adult education practice; and the first to attempt a comprehensive theory of adult education (via the notion of andragogy). Jarvis (1987: 185) comments:

As a teacher, writer and leader in the field, Knowles has been an innovator, responding to the needs of the field as he perceived them and, as such, he has been a key figure in the growth and practice of adult education throughout the Western world this century. Yet above all, it would be perhaps fair to say that both his theory and practice have embodied his own value system and that is contained within his formulations of andragogy.

Much of his writing was descriptive and lacked a sharp critical edge. He was ready to change his position – but the basic trajectory of his thought remained fairly constant throughout his career. His focus was increasingly on the delineation of a field of activity rather than on social change – and there was a significantly individualistic focus in his work. ‘I am just not good’, he wrote, ‘at political action. My strength lies in creating opportunities for helping individuals become more proficient practitioners’ (Knowles 1989: 146).

Further reading and references

Knowles, M. S. (1950) Informal Adult Education, New York: Association Press. Guide for educators based on the writer’s experience as a programme organizer in the YMCA.

Knowles, M. S. (1962) A History of the Adult Education Movement in the USA, New York: Krieger. A revised edition was published in 1977.

Knowles, M. S. (1970, 1980) The Modern Practice of Adult Education. Andragogy versus pedagogy, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall/Cambridge. 400 pages. Malcolm Knowles altered the subtitle for the second edition to From pedagogy to andragogy. Famous as his statement of andragogy – however, there is relatively little sustained exploration of the notion. In many respects it is a ‘principles and practice text’. Part one deals with the emerging role and technology of adult education (the nature of modern practice, the role and mission of the adult educator, the nature of andragogy). Part 2 deals organizing and administering comprehensive programmes (climate and structure in the organization, assessing needs and interests, defining purpose and objectives, program design, operating programs, evaluation). Part three is entitled ‘helping adults learn and consists of a chapter concerning designing and managing learning activities. In the second edition there are around 150 pages of appendices containing various exhibits – statements of purpose, evaluation materials, definitions of andragogy.

Knowles, M. S. (1973; 1990) The Adult Learner. A neglected species (4e), Houston: Gulf Publishing. 2e. 292 + viii pages. Surveys learning theory, andragogy and human resource development (HRD). The section on andragogy has some reflection on the debates concerning andragogy. Extensive appendices which includes planning checklists, policy statements and some articles by Knowles – creating lifelong learning communities, from teacher to facilitator etc.

Knowles, M. S. (1975) Self-Directed Learning. A guide for learners and teachers, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall/Cambridge. 135 pages. Programmatic guide that is rather objective oriented. Sections on the learner, the teacher and learning resources.

Knowles, M. S. et al (1984) Andragogy in Action. Applying modern principles of adult education, San Francisco: Jossey Bass. A collection of chapters examining different aspects of Knowles’ formulation.

Knowles, M. S. (1989) The Making of an Adult Educator. An autobiographical journey, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 211 + xxii pages. A rather quirky series of reflections on becoming an adult educator; episodes that changed his life; landmarks and heroes in adult education; how his thinking changed; questions he frequently got asked etc.

References

Brew, J. M. (1946) Informal Education. Adventures and reflections, London: Faber.

Brockett, R. G. and Hiemstra, R. (1991) Self-Direction in Adult Learning. Perspectives on theory, research and practice, London: Routledge.

Brookfield, S. B. (1994) ‘Self directed learning’ in YMCA George Williams College ICE301 Adult and Community Education Unit 2: Approaching adult education, London: YMCA George Williams College.

Candy, P. C. (1991) Self-direction for Lifelong Learning. A comprehensive guide to theory and practice, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Carlson, R. (1989) ‘Malcolm Knowles: Apostle of Andragogy’, Vitae Scholasticae,8:1 (Spring 1989). http://www.nl.edu/ace/Resources/Knowles.html

Davenport (1993) ‘Is there any way out of the andragogy mess?’ in M. Thorpe, R. Edwards and A. Hanson (eds.) Culture and Processes of Adult Learning, London; Routledge. (First published 1987).

Hewitt, D. and Mather, K. (1937) Adult Education: A dynamic for democracy, East Norwalk, Con.: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Jarvis, P. (1987a) ‘Malcolm Knowles’ in P. Jarvis (ed.) Twentieth Century Thinkers in Adult Education, London: Croom Helm.

Kett, J. F. (1994) The Pursuit of Knowledge Under Difficulties. From self-improvement to adult education in America, 1750 – 1990, Stanford, Ca.: Stanford University Press.

Knowles, M. S. and Knowles, H. F. (1955) How to Develop Better Leaders, New York: Association Press.

Knowles, M. S. and Knowles, H. F. (1959) Introduction to Group Dynamics, Chicago: Association Press. Revised edition 1972 published by New York: Cambridge Books.

Layton, E. (ed.) (1940) Roads to Citizenship. Suggestions for various methods of informal education in citizenship, London: Oxford University Press.

Lindeman, E. C. (1926) The Meaning of Adult Education (1989 edn), Norman: University of Oklahoma.

Merriam, S. B. and Caffarella, R. S. (1991) Learning in Adulthood. A comprehensive guide, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tennant, M. (1988, 1996) Psychology and Adult Learning, London: Routledge.

Yeaxlee, B. (1929) Lifelong Education. A sketch of the range and significance of the adult education movement, London: Cassell and Company.

Links

To cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2002) ‘Malcolm Knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogy’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/malcolm-knowles-informal-adult-education-self-direction-and-andragogy/. Retrieved: insert date].

Opening image: Where do I begin by That Damn Kat flickr | ccbysa4 licence

© Mark K. Smith 2002

updated: August 9, 2025

Malcolm Knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogy. A champion of andragogy, self-direction in learning and informal adult education, Malcolm S. Knowles was a very influential figure in the adult education field. Here we review his life and achievements, and assess his contribution.

Malcolm Knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogy. A champion of andragogy, self-direction in learning and informal adult education, Malcolm S. Knowles was a very influential figure in the adult education field. Here we review his life and achievements, and assess his contribution.