Robert Baden-Powell as an educational innovator. Famous for his contribution to the development of Scouting, Robert Baden-Powell was also able to make several educational innovations. His interest in adventure, association and leadership still repay attention today.

contents: introduction ·the early development of scouting · Robert Baden-Powell and ‘doing good’ · citizenship, taking responsibility and participation · harnessing the imagination: woodcraft and adventure · learning through doing · conclusion: robert baden-powell as an educational innovator · further reading and references · links · how to cite this article

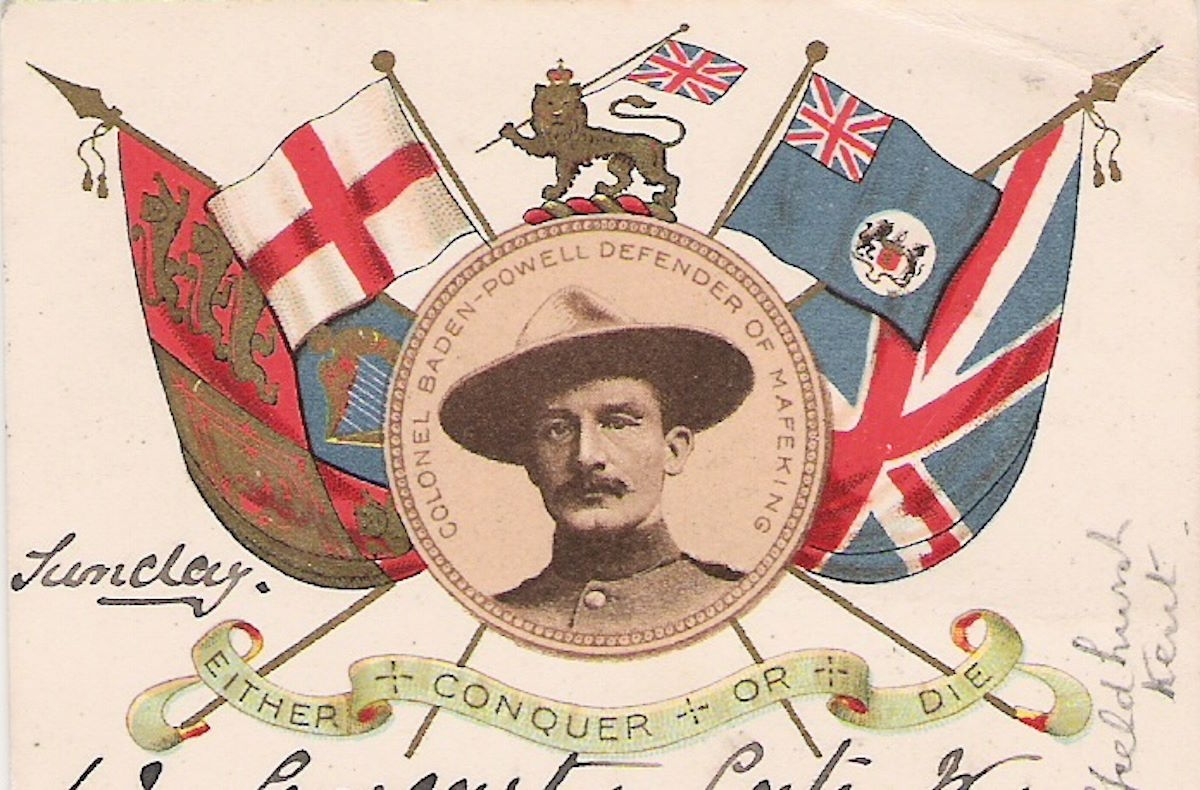

Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell (1857 – 1941) was an accomplished soldier who first came to wide public notice as the ‘hero of the Siege of Mafeking’(1899 – 1900) during the Boer War. He is better known as the founder of the Boy Scout movement. This achievement and his concern with ‘old values’ has sometimes obscured the innovational nature of his educational thinking. What is overlooked is his concern with the social lives and imagination of young people, and how he was able to build on this to develop an associational educational form. Robert Baden-Powell placed a special value on adventure; on children and young people working together – and taking responsibility (his ‘patrol’ building on the idea of ‘natural’ friendship groups and ‘gangs’); on developing self-sufficiency; and on ‘learning through doing’ (he was deeply suspicious of curriculum forms). In this article, we examine some of the key aspects of his approach.

Robert Baden-Powell and the early development of Scouting

In 1885 Robert Baden-Powell started collecting material for a book on army scouting. Eventually published in 1899, because of his celebrity status, it became an instant bestseller- selling more 100,000 copies within the first few months. The ideas were seized upon by a number of people working with boys and young men and Robert Baden-Powell was encouraged to write a version for boys. He was also working on his own ideas about education. The Boys Brigade (founded October 4, 1883, in Glasgow by William Smith [1854-1914) was an obvious place for his work – but while there were many things for Robert Baden-Powell to admire in their activities he was put off by the emphasis on drill and what he saw as a lack of attention to developing the mind and sympathy with others.

Robert Baden-Powell had become concerned about the well-being of the nation – and of, in particular, young people. It has been said that the poor physical condition of the young men attempting to join the army during the Boer War was a central factor in his championing and fashioning of Scouting. One report at the time (1904) claimed that of every nine who volunteered to fight, only two were fit to do so. Diet, poor housing, and harmful working conditions were identified as contributory factors. However, he was equally worried about people’s physical and mental well-being. Physical ‘deterioration’ and ‘moral degeneracy’ became themes in many of the talks and speeches that Robert Baden-Powell gave – especially in the period after the Boer War. Reflecting on his experience of the Boys’ Brigade he first thought that something could be done within that organization to move away from an over-focus on marching and drill:

Something, I think, also [could] be done towards developing the Boy’s mind by increasing his powers of observation, and teaching him to notice details. I believe that if some form of scout training could be devised in the Brigade it would be very popular, and could do a great amount of good. Preliminary training in this line might include practice in noting and remembering details of strangers; contents of shop windows, appearances of streets etc. The results would not only sharpen the wits of the Boy, but would also make him quick to read character and feelings, and thus help him to be a better sympathiser with his fellow-men. (Robert Baden-Powell in the Boys’ Brigade Gazette, 1 June 1904 – quoted by Jeal 1989: 362)

Having looked at various different schemes – including Ernest Thompson Seton’s vision of camping and woodcraft, and explored different educational forms, in August 1907 he conducted the famous Brownsea Island Experimental Camp. Robert Baden-Powell wanted to test out the ideas he had been working on for his scheme of work for ‘Boy Scouts’. He had completed the first draft of Scouting for Boys. With the experience of the camp validating much of his thinking, he began a long series of promotional lectures around the country arranged with the YMCA (Reynolds 1942: 147-8). On January 15, 1908, the first part of Scouting for Boys was published. Like modern-day ‘bit-parts’ it appeared at fortnightly intervals (6 parts) price at 4d each. It quickly appeared in book form (May 1). Sales were extra-ordinary and quickly groups of young men were approaching suitable adults to form troupes (Springhall 1977). The involvement of Arthur Pearson (the publisher) had given the whole enterprise an unedifying commercial edge. Robert Baden-Powell had unwisely entered into a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ with him – and had lost various rights and a large amount of money as a result. Considerable efforts were made to set up a separate organization and to limit the publisher’s power.

Scouting for Boys was also read and taken up by a significant number of middle-class girls on a self-organized basis (Kerr 1936: 16). In September 1908 at Crystal Palace the first big rally was held with some 10,000 Boy Scouts as well as a number of self-organized Girls Scouts attending (Reynolds 1942: 150). Robert Baden Powell was approached by some Girl Scouts asking him to do something for them also. In the second edition of Scouting for Boys he suggests a uniform for Girl Scouts – blue, khaki or grey shirt (as with the boys) and blue skirt and knickers. However, Robert Baden-Powell had decided to set up a separate organization and scheme. He decided ‘Scout’ was inappropriate and alighted on ‘Girl Guide’. The scheme was ‘to make girls better mothers and guides to the next generation’. In Robert Baden-Powell’s mind though, it was to be fairly similar in structure and activity as the boys – ‘Girls must be partners and comrades rather than dolls’ (Jeal 1989: 470). (Details of Baden-Powell’s ‘Scheme for “Girl Guides”‘ was published in the Scout’s Headquarters Gazette in November 1909. It is reproduced in full by Kerr [1932: 29-34]). With the move to Victoria, the Girl Guides were allocated a separate office and Agnes Baden-Powell (Robert’ sister) was asked to form a committee.

As John Springhall (1977: 64) has noted, in the decade from 1908 to 1919, ‘no other influence upon British boyhood came anywhere near Baden-Powell’s movement’. He continues:

The actual timing of the appearance of the first Boy Scout may be explained as an outcome of the post-Boer War mood of imperial decline and social reassessment… [H]owever, the historian needs to go back further, at least to Thomas Hughes idealization of Rugby and the ‘muscular Christianity’ of the third quarter of the nineteenth century. Despite subsequent new directions, the ideological roots of Scouting remain buried in the public school ethos of Charterhouse in the 1870s, the methods of colonial warfare in the 1880s and 1890s, and the intellectual climate of the 1900s.

The keywords of the old Scout Law: honour, loyalty and duty were part of the old public school tradition; and Robert Baden-Powell’s stress on the worth of activity and games (and disdain for ‘effeminate’ and intellectual scholarship) could have come directly from the pages of Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s Schooldays (Springhall 1977: 54). When this was combined with woodcraft and a love of the open air, a desire for class harmony and an appreciation of what might be happening in the imaginative life of boys then the scene was set for some serious innovation in informal education practice.

Robert Baden-Powell and ‘doing good’

One of the fascinating features of Robert Baden-Powell’s scheme is the centrality accorded to ‘doing good’. As we noted above, there is a strong link here with his own experience of public school. For some years prior to the publication of Scouting for Boys Robert Baden-Powell in his speeches to various youth groups and organizations had been encouraging boys and young men to ‘do good’. By ‘doing good’, he once wrote (in 1900), ‘I mean making yourselves useful and doing small kindnesses to other people – whether they are friends or strangers’ (quoted by Jeal 1989: 363). This concern famously became incorporated into Scout Law:

3. A scout’s duty is to be useful and to help others. And he is to his duty before anything else, even though he gives up his own pleasure, or comfort, or safety to do it. When in difficulty to know which of two things to do, he must ask himself, “Which is my duty?” that is, “Which is best for other people?” – and do that one. He must Be Prepared at any time to save life, or to help injured persons. An he must try his best to do a good turn to somebody every day.

4. A Scout is a friend to all, and a brother to every other scout, no matter to what social class the other belongs. Thus if a scout meets another scout, even though a stranger to him, he must speak to him, and help him in any way that he can, either to carry out the duty he is then doing, or by giving him food, or, as far as possible, anything that he may be in want of. A scout must never be a SNOB. A snob is one who looks down upon another because he is poorer, or who is poor and resents another because he is rich. A scout accepts the other man as he finds him, and makes the best of him.

“Kim”, the boy scout, was called by the Indians, “Little friend of all the world”, and that is the name that every scout should earn for himself. (Robert Baden-Powell 1908: 49-50 – these became laws 4 and 5 in the second edition of Scouting for Boys – 1909)

Conceptions of informal education such as that of Jeffs and Smith (1990, 1999) have also placed a strong emphasis upon seeking to live life well, and of looking to the well-being of others. However, such an approach (drawn from broadly from Aristotle and virtue ethics) clearly prioritizes the ‘good’ over the ‘correct’ – and this is a tension that Robert Baden-Powell would have found troubling. His conception of the good was deeply entwined with notions of duty – particularly towards his country. The Scout Law stated:

2. A Scout is loyal to the King, and his officers, and to his country, and to his employers. He must stick to them through thick and thin against anyone who is their enemy, or who even talks badly of them.

7. A Scout obey orders of his patrol leader or scout master without question.

Even if he gets an order he does not like he must do as soldiers and sailors do, he must carry it out all the same because it is his duty; and after he has done it he can come and state any reasons against it: he must carry out an order at once. That is discipline. (Robert Baden-Powell 1908: 49, 50)

For Robert Baden-Powell, then, there existed a possibility that those above in the hierarchy might have a questionable understanding of what might be for the best in a particular situation – but it is still the duty of the scout to carry out their wishes. Michael Rosenthal (1986: 162) has commented that the Scout Law and the overall direction of Scouting for Boys provided scouting with ‘a model of human excellence in which absolute loyalty, an unbudgeable devotion to duty, and the readiness to fight and if necessary die for one’s country, are the highest virtues’. Duty and patriotism were certainly central to Robert Baden-Powell’s vision – but so was kindness to others. The Scout Laws also call upon Scouts to smile and whistle, to be a friend to animals and to be courteous. What is less clear is what happens when there is a conflict between the different laws.

Citizenship, taking responsibility and participation

Keep before your mind in all your teaching that the whole ulterior motive of this scheme is to form character in the boys – to make them manly, good citizens…. Aim for making each individual into a useful member of society, and the whole will automatically come on to a high standard. (Baden-Powell 1909: 361)

In Scouting for Boys we can see that Robert Baden-Powell’s view of character is wrapped up with notions of citizenship. He wanted to encourage ‘a spirit of manly self-reliance and of unselfishness – something of the practical Christianity which (although they are Buddhists in theory) distinguishes the Burmese in their daily life’ (Baden-Powell: 1909: 292). This particular aspect of his vision was shared with a significant number of other workers at the time. While Robert Baden-Powell’s analysis of the social and moral situation in Britain certainly diverged from the more progressive thinking of Christian Socialists and many of the workers involved in the settlement movement, there were important commonalities. For example, he was opposed to extremes of wealth. In the first edition of Scouting for Boys (part VI, page 339), Baden Powell wrote:

[W]e are all Socialists in that we want to see the abolition of the existing brutal anachronism of war, and of extreme poverty and misery shivering alongside of superabundant wealth, and so on; but we do not quite agree as to how it is to be brought about. Some of us are for pulling down the present social system, but the plans for what is going to be erected in its place are very hazy. We have not all got the patience to see that improvement is in reality gradually being effected before our eyes.

This passage was to disappear in later versions of Scouting for Boys (from the third edition on), but it does establish that Robert Baden-Powell cannot be categorized in some simple way as ‘deeply conservative’. As Tim Jeal (1989: 413) has argued, there was more of an emphasis on taking responsibility and independent thinking than many commentators would allow. ‘A boy’, Robert Baden-Powell once wrote, ‘should take his own line rather than be carried along by herd persuasion’. In his list of ingredients of ‘character’, he places intelligence and individuality before loyalty and self-discipline (Jeal 1989: 413).

One of the fascinating aspects of Robert Baden-Powell’s scheme was his emphasis upon the group and of the young leader. In his reflections on the experimental camp at Brownsea Island he comments:

The troop of boys was divided up into ‘Patrols’ of five, the senior boy in each being Patrol Leader. This organization was the secret of our success. Each patrol leader was given full responsibility for the behaviour of his patrol at all times, in camp and in the field. The patrol was the unit for work or play, and each patrol was camped in a separate spot. The boys were put ‘on their honour’ to carry out orders. Responsibility and competitive rivalry were thus at once established and a good standard of development was ensured throughout the troop from day to day. (Robert Baden-Powell 1908: 344)

While not giving the degree of freedom, association, and lightness of adult intervention that characterized Seton’s vision of woodcraft, Robert Baden-Powell did, nevertheless, capture something. He connected with the way in which groups of boys often formed ‘gangs’ and then used that form as a way of creating an environment for learning and activity.

The patrol

[F]irst and foremost: The Patrol is the character school for the individual. To the Patrol Leader it gives practise in Responsibility and in the qualities of Leadership. To the Scouts, it gives subordination of self to the interests of the whole, the elements of self-denial and self-control involved in the team spirit of cooperation and good comradeship.

But to get first-class results from this system you have to give the boy leaders real free-handed responsibility-if you only give partial responsibility you will only get partial results. The main object is not so much saving the Scoutmaster trouble as to give responsibility to the boy, since this is the very best of all means for developing character.

The Scoutmaster who hopes for success must not only study what is written about the Patrol System and its methods but must put into practice the suggestions he reads. It is the doing of things that is so important, and only by constant trial can experience be gained by his Patrol Leaders and Scouts. The more he gives them to do, the more will they respond, the more strength and character will they achieve.

Robert Baden-Powell (1930)

Aids to Scoutmastership

http://old.jccc.net/~mbrownin/badenp/bp_scout.htm

As Robert Baden-Powell explained later, educators should ‘become the students, and … study the marvellous boy-life which they are at present trying vainly to curb and repress’. He went on ‘why push against the stream, when the stream, after all, is running in the right direction?’ (Baden-Powell 1930: 40).

Harnessing the imagination: woodcraft and adventure

Robert Baden-Powell wanted children to be brought up ‘ as cheerfully and as happily as possible’. He also wrote, ‘in this life one ought to take as much pleasure as one possible… because if one is happy, one has it in one’s power to make all those around happy’. (From a speech made in 1902 and reported in the Johannesburg Star July 10, 1902 – quoted by Jeal 1989). One of the great innovations of Scouting was to harness the imagination and desire on the part of many boys and girls for ‘adventure’.

Boys are full or romance, and they love ‘make believe’ to a greater extent than they like to show. All you have to do is to play up to this and to give rein to your imagination to meet their requirements. (Baden-Powell 1908: 356)

As we have seen, Robert Baden-Powell placed a special emphasis on adventure – on encouraging young people to look to enlarge their experiences. What had eluded him was a suitable framework to handle this and his other concerns – although he worked at various ways of approaching a scheme. Ernest Thompson Seton provided what he was looking for in his short book The Birch Bark Roll of the Woodcraft Indians. Seton had sent Robert Baden-Powell a copy of the book in 1906 – and Baden-Powell was impressed by the scheme of activities had designed around camp life. In Seton’s plan, groups of between 15-50 boys and young men were gathered together in a ‘band’ supervised by a ‘medicine man’. From this base, various activities and adventures could be undertaken – and the life and needs of the ‘band’ provided a useful reference point and organizing idea. Two further elements also impressed Robert Baden-Powell to ‘borrow’ them for his scheme. Seton had developed a system of non-competitive badges linked to the various activities in his programme. A similar range of badges with a non-competitive orientation was adopted by Robert Baden-Powell. Another element of the Seton scheme imported into Scouting was the use of a totem such as an animal or a bird to identify each Scout patrol.

The scale of this importation (some of which was not initially acknowledged properly) became the focus of considerable tension between Seton and Robert Baden-Powell.

Seton grew increasingly aggrieved at the plaudits conferred on Baden-Powell as the inventor of Scouting, a grievance obviously exacerbated by the enormous popularity of Baden-Powell’s movement as opposed to the substantially more modest success of his own Woodcraft Indians…. His resentment was nourished by a sense that Baden-Powell had betrayed the purity of the woodcraft ideal, substituting for the true woodcraft way, a narrowly self-serving military training that had nothing to do with real character building. (Rosenthal 1986 70; 71)

Rosenthal argues that Robert Baden-Powell’s encounter with Ernest Thompson Seton was ‘critical to the development of Scouting’ and that he was a ‘vital influence who brought before Baden-Powell the model of an efficient, attractive, self-contained system toward which he had been working for two years’ (ibid.: 80-81). The scale of the borrowing is disputed by Jeal (1989: 378) but even Rosenthal concludes that the structure produced by Seton’s idealism was transformed by Baden-Powell. To this extent, Robert Baden-Powell ‘engaged in a genuinely original, creative act’ (1986: 81).

Learning through doing

The key to successful education is not so much to teach the pupil as to get him to learn for himself.

Dr Montessori has proved that by encouraging a child in its natural desires, instead of instructing it in what you think it ought to do, you can educate it on a far more solid and far-reaching basis. It is only tradition and custom that ordain that education should be a labour. (Robert Baden-Powell manuscript circa 1913-14) quoted by Jeal 1989: 413)

In the process of preparing Scouting for Boys, Robert Baden-Powell read some quite diverse books and materials concerning the education of young men. Michael Rosenthal (1986: 64) lists some of his influences and they include: Epictetus, Livy, Pestalozzi, and Jahn on physical culture. He had also explored different techniques for educating boys within different African tribes, studied the Bushido of the Japanese, and the educational methods of John Pounds and the ragged schools (op. cit.). As we have already seen, he also drew upon the work of contemporaries such as William Smith, Ernest Thompson Seton and Dan Beard. He came to appreciate the philosophy and methods of Maria Montessori.

Be prepared

In his notes for instructors, Robert Baden-Powell discusses the need for Scouters (as they were later to be known) to have the ability to ‘read character, and thereby to gain sympathy’. Robert Baden-Powell also stresses ‘the value of patience and cheery good temper; the duty of giving up some of one’s time and pleasure for helping one’s country and fellow-men; and the inner meaning of our motto, “Be Prepared”‘ (1909: 295). He continues: But as you come to teach these things you will very soon find (unless you are a ready-made angel) that you are acquiring them yourself all the time.

You must ‘Be Prepared’ yourself for disappointments at first, though you will as often as not find them outweighed by unexpected successes.

You must from the first ‘Be Prepared’ for the prevailing want of concentration of mind on the part of boys, and if you then frame your teaching accordingly, I think you will have very few disappointments. Do not expect boys to pay great attention to any one subject for very long until you have educated them to do so. You must meet them half way, and not give them too long a dose of one drink. A short, pleasing sip of one kind, and then off to another, gradually lengthening the sips till they become steady draughts….

This making the mind amenable to the will is one of the important inner points in our training.

For this reason it is well to think out beforehand each day what you want to say on your subject, and then bring it out a bit at a time as opportunity offers – at the camp fire, or in intervals of play and practice, not in one long set address….

To get a hold on your boys you must be their friend; but don’t be in too great a hurry at first to gain this footing; until they have got over their shyness of you.

Robert Baden-Powell (1909)

Scouting for Boys, pages 295 and 294

There was a strong antipathy in some of Robert Baden-Powell’s writing to rote learning, the attempt to cram information into ‘young heads’ and abstract ideas that were not tied to practical expression. As an educational approach this element along with Robert Baden-Powell’s concern with ‘training for active citizenship’, his focus on character, ‘the appreciation of beauty in Nature’, and service to others (Baden-Powell 1930) appealed strongly to many progressive headmasters (like Cecil Reddie at Abbotsholme). Such thinking also found its way into various experiments in education – such as that undertaken by Leonard Elmhirst and Rabindranath Tagore in India. One of the key concerns in that work was to utilize scouting and woodcraft as a way of developing forms of schooling for village children that ‘took full account of their natural surroundings’ (Stewart 1968: 129).

Conclusion: Robert Baden-Powell as an educator innovator

How are we to judge Robert Baden-Powell as an educator? While the ‘faculty psychology’ on which he based significant elements of his scheme may be discredited (Macleod 1983: 251) and his imperial vision of duty is distasteful to many – there is still much to admire and acknowledge in Robert Baden-Powell’s work. He did look to the social lives and imagination of children and young people. He placed a special value on adventure; on children and young people working together – and taking responsibility (his ‘patrol’ building on the idea of ‘natural’ friendship groups and ‘gangs’); on developing self-sufficiency; and on ‘learning through doing’. It was one of the ironies of youth work from the 1960s to the 1990s that while club and project workers may have talked of participation and questioned many of the methods of uniformed organizations, the most sustained and widespread example of self-organization and participation flows from Robert Baden-Powell’s scheme set out in 1908. It may well be that we need to look again at notions of character, virtue and duty – to see how they may be reinterpreted for today’s conditions and within a more dialogical, just and convivial framework.

Further reading and references

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1899) Aids to Scouting for NCOs and Men, London: . Robert Baden-Powell’s first bestseller – whose central message was that military scouting bred self-reliance. This was achieved because they had to use their intelligence and act on their own initiative. Scouts frequently operated away from the guidance of officers.

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1908) Scouting for Boys. A handbook for instruction in good citizenship, London: Horace Cox. 398 pages. First published in six fortnightly parts in 1908 (at 4d. per part) a combined volume was quickly republished in the same year. A second edition appeared in 1909 (Arthur Pearson, 310 pages) – and there have been various editions since. The original bit part version was republished by the Scout Book Club in 1938. The cover of Part One (see right) was by John Hassell and as Tim Jeal has said, the implication was clear – this was an invitation not to just read about adventures but to live them too. Its impact was phenomenal – with four reprints in the first year and well over 60,000 copies sold in its second year. Part one dealt with scoutcraft and scout law; part two with observation and tracking, woodcraft and knowledge of animals. Part three looked at campaigning and camp life, pioneering and resourcefulness; part four with endurance and health, chivalry and brave deeds, discipline; part five with saving life and first-aid, patriotism and loyalty. Finally, part six dealt with scouting games, competitions and plays, plus words to instructors.

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1922) Rovering to Success. A book of life-sport for young men, London, Herbert Jenkins. 253 pages. Basically, advice to young men on how to avoid pitfalls around gambling, drinking, sexual temptation, (political) extremists and irreligion.

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1929) Scouting and Youth Movements, London, Ernest Benn.

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1930) Aids to Scoutmastership: A Guidebook For Scoutmasters On The Theory of Scout Training, London: Herbert Jenkins. Online version: http://old.jccc.net/~mbrownin/badenp/bp-aids.htm. With chapters on the scoutmaster, the boy, scouting, character, health and strength, handicraft and skill, and service to others, this book provides a collection of thoughts and hints based on the experience of the scheme.

Jeal, T. (1989) Baden-Powell, London: Hutchinson. Brilliant, balanced and extremely well-researched biography.

Reynolds, E. E. (1942) Baden-Powell, London: Oxford University Press. This is an ‘official’ reading – undertaken at the request of the Scout Association. That said, it does contain a good deal of interesting detail. Online at: http://www.pinetreeweb.com/bp-reynolds.htm

Rosenthal, M. (1986) The Character Factory. Baden-Powell and the origins of the Boy Scout Movement, London: Collins. A controversial study that dwells heavily on Baden-Powell’s supposed racism, militarism and homosexuality and on his ideas on ‘character’. Well worth reading – especially alongside Jeal (1989).

References

Baden-Powell, A. and Baden-Powell, Robert (1912) How Girls Can Help Build Up the Empire, London.

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1908) Scouting for Boys. A Handbook for instruction in good citizenship, London, Horace Cox.

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1909) Scouting for Boys. A handbook for instruction in good citizenship. (rev. edn.), London, Pearson.

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1916) The Wolf Cub’s Handbook, London, Pearson.

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1941) B-P’s Outlook. A selection of articles for the Scouter, London, Pearson.

Jeffs, T. and Smith, M. (1990) Using Informal Education. An alternative to casework, teaching and control?, Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Jeffs, T. and Smith, M. K. (1999) Informal Education: Conversation, democracy and learning, Ticknall: Education Now.

Kerr, R. (1932) The Story of the Girl Guides, London, Girl Guides Association.

Macleod, D. I. (1983) Building Character in the American boy. The Boy Scouts, YMCA and their forerunners, Madison: Wisconsin University Press.

Springhall, J. (1977) Youth, Empire and Society. British youth movements 1883-1940, Beckenham: Croom Helm.

Stewart, W. A. C. (1968) The Educational Innovators. Volume II: Progressive schools 1881-1967, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Links

Go no further than the truly excellent US site Pine Tree Web. This is a comprehensive collection of material about Scouting across the world and has extensive material on Baden-Powell.

Acknowledgements: Picture: postcard celebrating Robert Baden-Powell 1900, believed to be in the public domain as the work was published before January 1, 1923 and it is anonymous or pseudonymous due to unknown authorship. Sourced from Wikipedia Commons: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baden_Powell.jpg.

To cite this article: Smith, M. K. (1997; 2002; 2011). ‘Robert Baden-Powell as an educational innovator’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/robert-baden-powell-as-an-educational-innovator/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K. Smith 1997, 2002, 2011

updated: August 11, 2025