featured

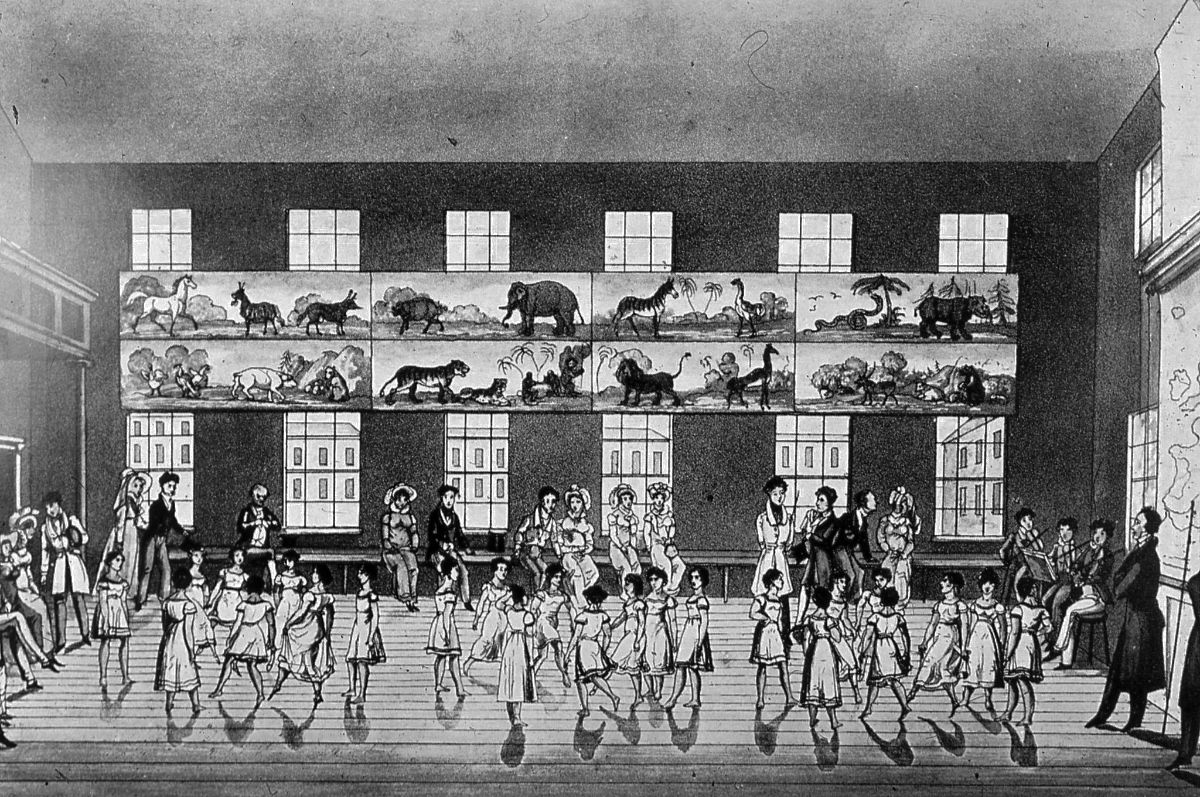

Education in Robert Owen’s new society: the New Lanark institute and schools. Robert Owen’s educational venture at New Lanark helped to pioneer infant schools and was an early example of what we now recognise as community schooling. Yet education was only a single facet of a more powerful social gospel which already preached community building on the New Lanark model as a solution to contemporary evils in the wider world. Ian Donnachie investigates.

Exploring the nature of social action [through a walk in Bermondsey and Rotherhithe in London]. This area has experienced severe poverty and disadvantage over the years. Settlements, missions and various government bodies have been involved in trying to stimulate change – and some notable innovations were made. However, support and important changes also came from local people and their organizations. [updated September 2025]

Mary Augusta Ward | Mrs Humphry Ward and the Passmore Edwards Settlement. Mary Ward aka Mrs Humphry Ward was one of the best-known writers of her day. She was also a key pioneer in the settlement movement and the development of provisions for children with disabilities and for play. Alongside this, Mary Ward was an advocate for the rights of women, yet she opposed the extension of the right to vote to them. We explore her life and contribution, and the settlement she founded. [updated and extended August-September 2024 and November 2025]

Ivan Illich on deschooling, conviviality, and systems. Possibilities for education and social change. Known for his critique of modernization and the corrupting impact of institutions, Ivan Illich’s concern with deschooling, learning webs and the disabling effect of professions struck a chord among many educators and pedagogues. We explore some key aspects of his theories and his continuing relevance for teaching, pedagogy and learning. [Updated and extended January 2025]

new [and updated]

The Mixed Club. A Statement of its general aims and functions. Published in 1948, this publication from The National Association of Girls’ Clubs and Mixed Clubs sets out what they viewed as the purpose, nature and job of mixed clubs. It also discusses the sort of activities and leadership involved, and the future of mixed clubs. [New in the Archives November 2025].

What is pedagogy? A definition and discussion. Pedagogy is often, wrongly, seen as ‘the art and science of teaching’. Mark K. Smith explores the origins and development of pedagogy and finds a different story – accompanying people on their journeys. Teaching is just one part of what they do. [Updated October 2025].

Josephine Macalister Brew, youth work and informal education. One of the most ‘able, wise and sympathetic educationalists of her generation’, Josephine Macalister Brew made a profound contribution to the development of thinking about, and practice of, youth work and informal education. [Updated September 2025]

Girls in the Nineteen Sixties – Mary Robinson. This landmark booklet, first published in 1963, set out why youth workers should focus more strongly on the specific needs of young women. [New in the archives July 2025].

YMCA and the development of informal and youth work education. In this major new piece, Tony Jeffs reflects on the YMCA’s 135-year engagement across the world with the professional education of those working with young people. He examines both the innovations and tensions involved in the growth and experience of different programmes, and the factors that led to the decline of informal and youth work education within the YMCA. This important research is also available to download as a pdf [updated May 2025].

Ellen Ranyard (“LNR”), Bible women, district nurses and informal education. Known for using innovative methods, Ellen Raynard (1810-1879) brought about the first group of paid social workers in England and pioneered the first district nursing programme in London. [updated and extended April 2025]

Our opening picture: New Lanark School [J R James Archive] is used here under a ccbync2 licence.