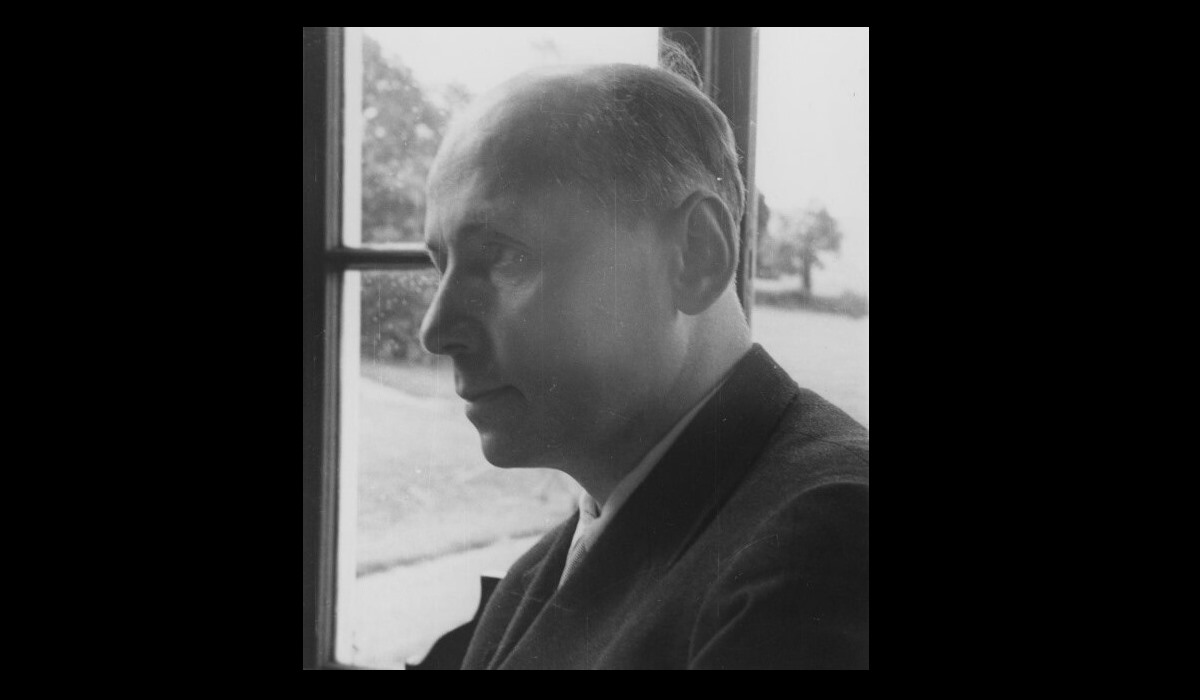

Kurt Hahn, outdoor learning and adventure education. A key figure in the development of adventure education, Kurt Hahn was the founder of Salem Schools, Gordonstoun public school, Outward Bound, the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme and the Atlantic Colleges.

Kurt Mathias Robert Martin Hahn (1886 – 1974). German educationalist, born in Berlin, who founded the Salem Schools (Castle Salem 1920), Gordonstoun public school (1934). Outward Bound (1941), the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme (1954 – 6) and the Atlantic Colleges (1957). Kurt Hahn was educated at Wilhelm Gymnasium, Berlin, University of Göttingen and Christ Church, Oxford (where he studied philosophy and classics). He also had spells at a number other universities. Early on he decided to be a schoolmaster. The work of Plato was one of his formative influences and gave some direction to his thinking.

Kurt Hahn valued the contribution of English public school education to the development of ’rounded’ character (his first port of call were some of the more progressive institutions such as Abbotsholme – but he later came to admire more traditional boarding schools. His first school was founded at the castle and estate of Prince Max von Baden (Salem near Bodensee). Von Badem had been the Imperial Chancellor for two months in late 1918 – but Hahn had been his private secretary whilst serving in the Foreign Press Centre of the German Foreign Office. Whilst in that capacity he had written a highly critical report on the dangers of submarine use (it would bring the Americans into the war) for which he was sacked. This is said to be significant moment in the development of his thinking. What Kurt Hahn had said was shared by many others in government but who were seemingly too frightened to speak out. He concluded that there was a need to educate so that people would speak of their convictions.

Exhibit 1: The seven laws of Salem

These principles were set out in a document written in 1930 (and quoted in Flavin 1996: 15 – 17).

1. Give the children opportunities for self-discovery.

2. Make the children meet with triumph and defeat.

3. Give the children the opportunity of self-effacement in the common cause.

4. Provide periods of silence

5. Train the imagination.

6. Make games important but not predominant.

7. Free the sons of the wealthy and powerful from the enervating sense of privilege.

This approach emphasized character-building and, to some extent, down played the development of intellectual ability (although this should not be over-done – students were educated for the school certificate). A fairer statement might be that they were able to work (academically) more at their own pace.

Kurt Hahn was arrested in 1933 after he had spoken out against Hitler’s congratulation of five storm-troopers convicted of murdering a young communist. However, there are certain elements in his approach which bear some similarity to the thinking and practices of the German Youth Movements (the Hitler Jugend) – the emphasis on self-effacement in the common cause, on the body and athleticism, and his concern for character and ‘race’. Given his Jewish background he said surprisingly little about the holocaust. Hahn was released, came to Britain and quickly founded Gordonstoun. Among his first pupils was Prince Philip (who transferred from Salem).

One of Kurt Hahn’s early innovations was the introduction, with a local school, of the Moray Badge, a County Award. It was to be awarded when people met a certain standard in track and field, expeditions and life saving. It was this idea that was to be developed into the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme. Indeed, the development of the Award is a testament to Hahn’s ability as a ‘mover and shaker’. He kept on at Prince Philip to put his name to the scheme and persuaded John Hunt (the leader of the first successful Everest expedition) to be its first Director.

Outward Bound also grew out of Kurt Hahn’s Gordonsoun activities. There had been some emphasis on sea training and coastguardship at Gordonstoun, but when the school moved to its wartime home near Aberdovey, the idea of sea training and of learning from the sea took root. The first Outward Bound Sea School was founded in 1941 – and the practice of short challenging courses (26 days) for boys from industry – complete with a confidential report on their behaviour and performance under pressure – quickly became established.

From this review it can be seen that Kurt Hahn’s contribution lay less in his abilities as an original thinker or educator, but rather in his capacity to set out a vision, to convince people to fund and sponsor that vision – and to pick the right people to develop the work. He does seem to have had some ability to connect with young men. Kurt Hahn could be over-powering and rather autocratic.

Kurt Hahn’s emphasis on experience and ‘experiential therapy’ can be seen as deriving from educationalists such as Pestalozzi and Dewey. His concern for service and helping could be seen as coming from ‘old aristitocratic’ values (he often quoted Prince Max’s remark that the goal should be ‘a sense of responsibility to humanity’). There was the Platonic ideal (paideia) – the development of energetic participation’ and the Jamesian notion of psychological motivation as an aid to self knowledge.(For a discussion of this see Röhrs’ helpful chapter in Röhrs and Tunstall-Behrens [1970] – see below).

References

Bibliographical material: Sadly, there is no full length, critical exploration of Kurt Hahn and his work. Two somewhat different starting points are:

Flavin, M. (1996) Kurt Hahn’s School and Legacy. To discover you can be more and do more than you believed, Wilmington, Delaware: Middle Atlantic Press. 163 + xii pages. The opening chapter provide a potted history of the Salem schools, Gordonstoun and Outward Bound; the second half of the book is basically a reflection on the author’s experience of Salem in 1933-4 and the subsequent development of the school. This makes the book a bit of an odd read – but it does have the virtue of communicating something of the flavour of the approach.

Röhrs, H. and Tunstall-Behrens, H. (eds.) (1970) Kurt Hahn. A life span in education and politics, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. 268 + xxiii pages. Collection of pieces that explore different dimensions of Hahn’s work with some interesting insights e.g. Ewald on Salem, Brereton on Gordonstoun, Röhrs on his educational philosophy and Mann on his political activities.

Links

KurtHahn.org: Site dedicated to his philosophy with some archival materials and writings.

Acknowledgements: The photograph of Kurt Hahn is by Howard Coster and used here with the permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London [NPG x20859] ccbyncnd3 licence. The map image is reproduced with the permission of the Hollowford Centre. All rights reserved See our outdoor learning feature and visit the Hollowford site: http://www.hollowford.org/

© Mark K. Smith 1997.

Last updated on August 14, 2025