Chapter 3 of Mark Smith’s exploration of youth work and social education – Creators not Consumers. Rediscovering social education (1982).

contents: · developmental needs · values · conclusion ·

[page 24] So far we have been looking at a form of youth work that puts learning first. In this chapter I want to ask what makes this form of learning special enough to have its own label — social education?

Our starting point will be a discussion of the major reasons for wanting to ‘socially educate’ people and the forming of the following definition:

Social education is the conscious attempt to help people to gain for themselves, the knowledge, feelings and skills necessary to meet their own and others developmental needs.

We will then go on to examine some of the value issues involved in social education and, in Chapter 4, the political implications of this view.

Developmental needs

The view of social education advocated here is initially based on two beliefs:

- All members of society have the right to a full emotional, social and intellectual development.

- Society has an obligation to ensure that people get access to the resources and opportunities that enable such development.

One way of looking at what these developmental needs are has been put forward by Mia Kellmer Pringle (see Figure 5). She suggests that there are four significant developmental needs:-

a. The need for love and security

b. The need for new experiences

c. The need for praise and recognition

d. The need for responsibility (Mia Kellmer Pringle, The Needs of Children, Hutchinson, 1980)

These needs are met in a variety of ways — by the family unit, school, work, friends etc. In this sense, social education is not just the property of youth work. The relative importance of each of these areas varies through time and with age. For instance, certain needs will be more important in adolescence than in early childhood. During adolescence (which I take to mean the period from puberty to about the age of maturity — in other words from around age 11 to about 18 years) a number of significant things are happening. Young men and women are having to:

- come to terms with new and sometimes worrying physical experiences such as the boy’s first ‘wet dream’ or the girl’s first period.

- explore their sexual identity

- answer questions concerning job choice and employment/ unemployment

- change their relationships with parents, friends, adults

- develop a self concept/identity.

[I’ve chosen to use this framework as it presents developmental needs as being interrelated and interdependent. Other formulations such as ‘Maslows Triangle’ suggest that such needs operate in a hierarchical sequence. The most basic needs are for sheer survival (like the needs for food, water and shelter). Only when these have been met do other needs emerge (like the need for a loving relationship). There is now a great deal of evidence to show that things do not operate is such a smooth way.]

Looking at this list of ‘new experiences’ there is a danger of getting a rather melodramatic view of adolescence. Most young people are able to get through this period without great ‘storm and stress’. This is not to say that they will not experience difficulties or do not need help, but simply a plea to keep things in perspective. Nor should we forget the significance of adolescence and other critical periods of transition. In recent years it has become increasingly clear that the experiences of adolescence rate in equal importance with those of the first five years of life in their effect on what happens in later life. (John Coleman gives a good summary of the evidence here see Further reading).

[page 26]

Figure 5: Developmental NeedsMia Kellmer Pringle has suggested that there are four significant developmental needs which have to be met from birth. These are: a. The need for love and security b. The need for new experiences c. The need for praise and recognition d. The need for responsibility Adapted from Mia Kellmer Pringle, The Needs of Children, Hutchinson, 1980 |

[page 27]

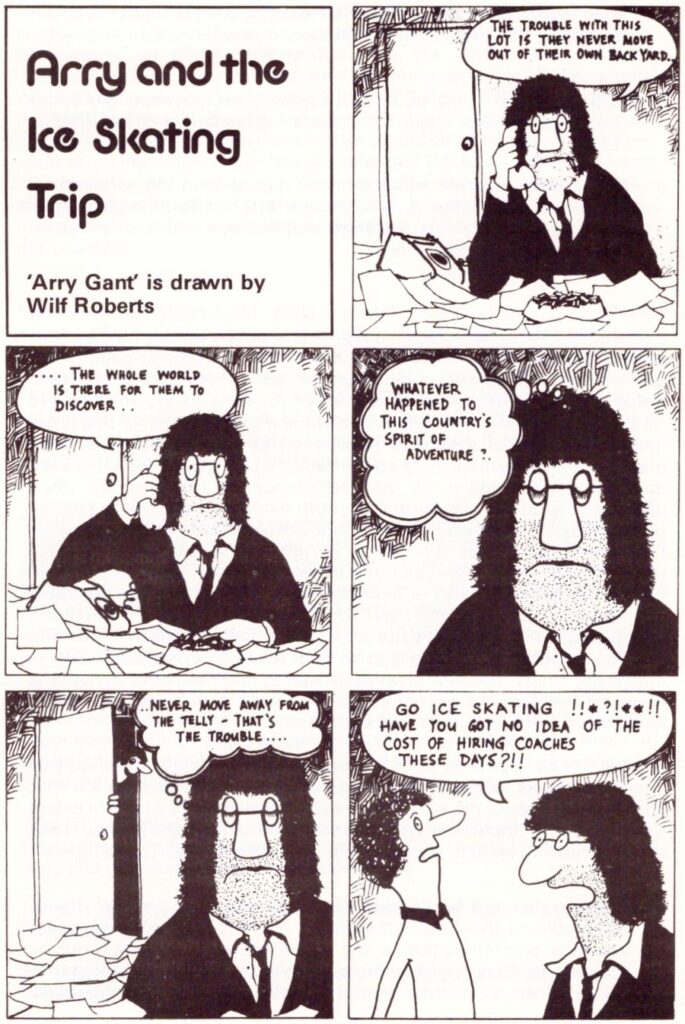

If we examine these developmental needs we can see that the skating trip workers were working in all four areas. In their relationship with Neil, (the instigator of the trip), they were particularly concerned with his self-centredness and apparent inability to take responsibility for his own actions. Over a lengthy period they had tried to show he mattered to them and as the relationship began to be reciprocated, (albeit in occasionally peculiar ways), their concern shifted. They encouraged him to take on new roles — such as that of ‘organiser’ and they tried to reinforce his behaviour in these roles with encouragement and support. In the case of the trip we see them seeking to get his acceptance of a degree of responsibility for others.

The majority of young people these workers were dealing with could not be considered as having such profound difficulties in making and keeping relationships. They at least had a relatively secure personality base from which they could handle new experiences. These young people were beginning to take responsibility for their own lives and were seeking an identity and view of the world that was of their own making. Decisions, for instance about sex, were being taken that could no longer be discussed in the family. They therefore desired a more independent and equal relationship with adults than that found at school or home. The workers saw these needs for ‘autonomy’, for responsibility and new experiences, as being the primary areas for their attention. However this didn’t stop them from trying to meet other needs as they were recognised.

When youth workers’ efforts are put into the total context of young people’s lives it quickly becomes apparent that there is the need for some humility about how much they can achieve. As we have seen young people are having to handle experiences and take on new roles that many find difficult to talk and think about in the family or at school. They often need the help of sympathetic outsiders (like youth workers), but the family (in particular) and the school are still very powerful forces in determining young peoples’ life chances and attitudes. However the ice skating workers demonstrate that youth workers can have a unique and special role. The intervention of youth workers can be significant in many young peoples’ lives and crucial in some.

The use of developmental needs has three further important implications for social education. Firstly, whilst earlier approaches to social education have usually centred on the idea of adults helping young people, a developmental needs approach doesn’t make that assumption. It recognises that adults also have social educational needs and that these can be met by young people. In addition it takes into account of the help young people give each other, for instance the caring [page 28] and security they get through friendships. This whole area of mutual aid is crying out for youth workers’ attention. The tendency has been to concentrate on direct intervention with the person who has the ‘problem’ rather than to work through intermediaries. For instance when a young person has to appear in court for the first time the worker might sit down with the person concerned and run through what an appearance involves. How much better would be an approach that gave another young person who had actually had the same experience and who uses the same language, the knowledge, feelings and skills to be able to answer questions and give support. Not only do you answer the first person’s need but you also extend another person’s competence in the process.

Secondly, a developmental needs approach, like other ways of looking at social education, places a special emphasis on groups. These needs are largely met through interaction with others and the experience of being a member of a group. Groups are essential parts of human existence. They provide us with both a sense of belonging and the experience necessary for the creation of our own separate identity. It is also necessary to work collectively in order to influence the political system so that all developmental needs be met.

Thirdly, the employment of developmental needs neatly side-steps the definitional problems involved with the concept of ‘maturity’. The achievement of this state has usually been the central aim of previous approaches. By adopting developmental needs we are saying that our central concern is personal growth rather than the attainment of the magical status of being a ‘mature person’. In other words we are defining maturity as the search for maturity.

If the meeting of developmental needs is seen as a ‘problem’ then certain knowledge, feelings and skills will be necessary to fulfill them. Added to the comments made above we can move towards a definition of social education as follows:-

“Social education is the conscious attempt to help people to gain for themselves, the knowledge, feelings and skills necessary to meet their own and others developmental needs.”

To sum up, this definition has substantial advantages over previous formulations. It is:-

- Unambiguous — it avoids the lack of clarity engendered by the use of words like maturity. [page 29]

- More dynamic — the concept of developmental needs and the knowledge, feelings, skills framework provide prescriptions for action.

- All embracing — social education is not seen as the property of youth work but of several major institutions — schools, the family, friends etc.

- Conscious — people often confuse social learning with social education. Education is a deliberate attempt to change people.

Learning is what is gained from that process and from all social situations (intended or not).

From the cover of the first edition of Creators Not Consumers

Values

Education is about conscious change. It is about trying to alter people in some way. The direction which it takes, the changes in people that workers see as desirable, depend on the values we bring to the work. Value questions run through all that youth workers do, yet they are rarely talked about in any detail. One of the major reasons for this is the inconsistencies that often emerge between our personal values and our practice. It is altogether more comfortable not to question what we are doing. Another reason for our reluctance, is that we are often apprehensive about admitting that youth work is an attempt to change people in a particular way. Workers who are connected with movements that have strong ideas about what is right and wrong, such as those involved with church groups, tend to be most clear about this. We all have ideas about the sort of behaviour and feelings that are desirable and these ideas rightly and inevitably influence the way we work with young p eople even if we are not entirely conscious of the fact. The first step any educator must take is to be clear about these values. Clarity is important, firstly, because clear aims lead to more effective action and secondly because the people you are working with have the right to know what you are trying to do with them.

In what has been written so far it is possible to see nine broad ideas that might qualify as values. These ideas would seem to have an intrinsic worth and are about the way workers should operate. To a certain extent these ‘doing’ or ‘instrumental’ values are also some of the very qualities social educators want to encourage in the people they are working with.

- Problems should be defined by the person who “owns” them. The problems should be self-defined— it is not up to the worker to say what the problem is but for the person/persons to work it out for themselves. People will be more motivated to solve a problem they have defined rather than what the worker has said they should do. This is sometimes known as peoples ‘right to self determination’. [page 30]

- Seeing the good in everyone. We need to accept people as they are and not as what they could become. It is essential to be optimistic about people’s potential so as not to limit their growth. In other words we must try to like and respect the people we work with.

- Honesty. Explicitness is important, that is people need to understand exactly what is happening. More broadly openness is also valued. Work should be carried out in a spirit of ‘straightforwardness’, not having something ‘up your sleeve’. A part of this is the need to be oneself and to be able to talk about your own feelings etc.

- Consistency. Workers should deal with young people evenly. They need to do this in order that they gain people’s trust. Consistency also implies management, that workers are clear about their aims, methods of working and evaluation, that is they need to be disciplined in their approach.

- Flexibility. Whilst being consistent, workers also need to be flexible, as different people and situations need different responses. This implies that the worker should not start from a narrow ideological base but have a choice of theories and practice at his/her disposal.

- Common Sense. This is a belief that reason should be applied to all situations, that whilst feelings are very important, it is important to try and look on those feelings “objectively”.

- Freedom of Choice. Whilst it is the responsibility of the workers to offer help, people must be free to choose whether they take up the offer. The offer itself must enhance the individual or group’s freedom to choose.

- Equality. The desired relationship between the workers and the young people is two way, mutual, not leader/led. Both workers and young people have needs to be satisfied. The problems/needs which are at the centre of youth work are ‘owned’ by young people and are for them to define. The worker’s role is to help people to better understand and take action on needs and possible solutions and that role can only be on an equal footing.

- Confidentiality. Ownership of problems must be respected. What the worker hears about problems should be treated as confidential and passed onto others only if permission is given.

[page 32] This list of values shows up some of the ethical problems that workers experience. It shows how difficult it is for a worker to be morally neutral (even if that is desirable). Even the very act of intervening in peoples lives is based on certain value assumptions:

- people should not passively accept their conditions but actively intervene to change them.

- people should plan ahead.

Workers would be less than human of their values did not show through in their work. For instance if the worker is counselling a pregnant young woman who is very unsure about having an abortion, it is likely they themselves would favour one decision or course of action. The way questions are phrased, the information provided and the tone of the conversation are bound to influence the person in some way. To this must be added the fact that people frequently expect workers to be moral agents.

Lastly there is a question about how absolute these values are. Is it always right to keep confidences? Are there times when a worker should lie? Should workers respect a young persons determination to be dishonest or irrational?

We can see here the makings of a real contradiction — if, as educators, we are trying to alter people in some way, does this not place limits on their right to self determination?

Such tensions are an inevitable part of working with people. To some extent the dilemmas can be eased by workers:

- Knowing their own values. When workers are clear about their own values they are more likely to be aware of their own attempts to smuggle those values into their work.

- Being open about their own values. By being open the worker lets other people know where they stand and they can then act accordingly.

- Ensuring that any action they take actually enhances peoples’ freedom of choice. Workers should enable people to have experiences that gives them the knowledge, feelings and skills necessary for them to be able to make choices and so make real their values. (Value dilemmas such as those discussed in Allen Pincus and Anne Minahan, Social Work Practice: Model and Method, Peacock, 1973.)

[page 33] As these conclusions make clear there are no simple solutions to value problems in social education. Each situation has to be judged on its own merits. However, what this discussion does indicate is that an awareness of such ethical considerations must become a part of the basic beliefs of social education.

In conclusion

This chapter has put forward the idea that social education is the conscious attempt to help people to gain for themselves the knowledge, feelings and skills necessary to meet their own and others developmental needs. It has suggested that:

- All members of society have the right to a full emotional, social and intellectual development.

- Society has an obligation to ensure that people gain access to the resources and opportunities that enable such development.

- The help given to people must be based on truth and reason and enhance human freedom and dignity.

In the next chapter we will see that such a full development can only be achieved and maintained by action at both an individual and a collective level.

Mark Smith (1982) Creators not Consumers. Rediscovering social education 2e, Leicester: National Association of Youth Clubs.

Reprinted with the permission of Youth Clubs UK.

Chapter 3: pages 24 – 33.

© Mark K. Smith 1980, 1982

updated: August 20, 2025