This piece provides an insight into the way in which parish visitors approached their tasks – in particular, how they related schooling and club work to outreach. Taken from Chapter IX of Maude Stanley’s (1878) Work About The Five Dials, London: Macmillan.

Maude Stanley, the third daughter of the 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley, was involved in district visiting in St Annes, Soho (the forerunner of the casework element of social work). She lived in Smith Square (No. 32) close to the Houses of Parliament. A co-worker with Octavia Hill (Steman Jones 1984: 204), she argued that more people should be involved in the sort of work and visiting undertaken by the Charity Organisation Society. In the Five Dials area, she was again involved in home visiting – and could bring an ‘exact and critical knowledge of the existing agencies for the relief of poverty and suffering (Eager 1953: 66).

A lively account of her work is given in Work About the Five Dials (1878) and it included setting up a refuge, developing Sunday Schools, night classes and a ‘club’. She set out to involve local people as teachers and helpers; and made contact with young men and women on the streets and in the courtyards – as they talked and played cards and gambled.

Stanley’s significance for youth work is great. She wrote the first substantial text on clubs for girls (1890); and took some efforts to facilitate inter-club links – establishing the Girls Club Union in 1880. It later became known as the London Girls’ Club Union and, along with the Federation of Girls Clubs (run under the auspices of the YWCA) and the Social Institutes Union, was reconstituted in the late 1930s as the London Union of Girls (then Youth) Clubs. Currently known as London Youth.

links: Maude Stanley, club work, working men’s college, Sunday schools, ragged schools.

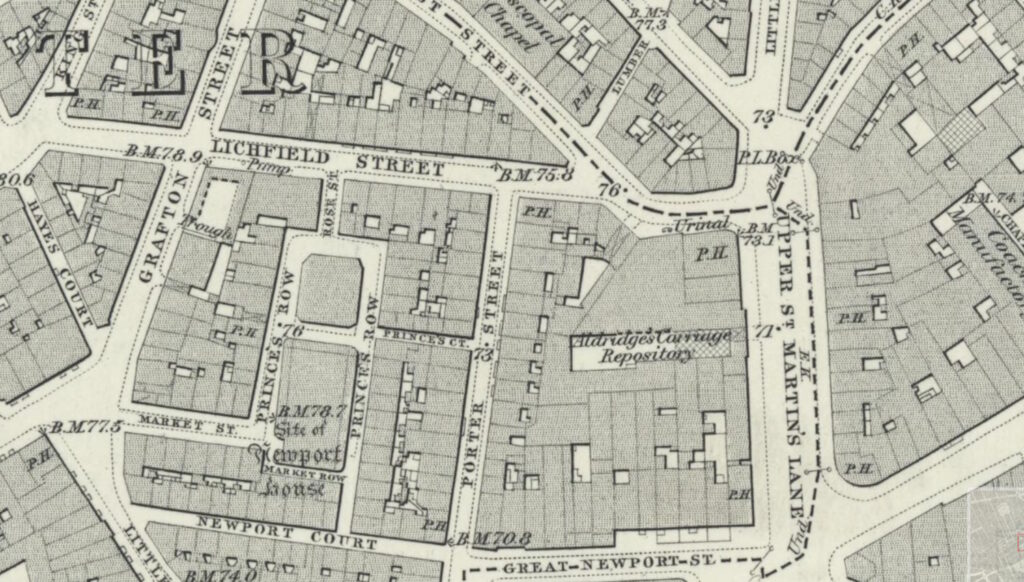

Map: part of the Five Dials area as shown on an OS 25-inch map published in 1875 – and believed to be in the public domain. See National Library of Scotland. Most of the people mentioned in Maude Stanley’s opening remarks lived around Leicester Square and Soho, which is just beyond the left edge of the map.

______

The district of which I have hitherto been speaking is very near the West End of London, and was formerly a most aristocratic part of the town. By the china tablets fastened against some of the houses in this neighbourhood, we see where Dryden, Burke, and Sir Joshua Reynolds lived, but now these houses are each occupied by several families of working-people.

The Duke of Monmouth had also a house close to the Dials, and his room can still be seen just as he left it, his arms painted on the panelled walls, and carved in wood over the chimney piece; the ceiling is heavily decorated, and you can fancy yourself when in that room once more in the days of the Stuarts, instead of being in the very centre of a great warehouse, which sends out its goods to all parts of the world, and represents well the active trade and the toil of the nineteenth century. The Duke of Grafton also lived close by: but though the house still bears his name, it has no remains of former greatness, and is now occupied like the other houses I have mentioned, by several families of working people.

In the poorest part of the parish is a building used partly as an Industrial School, partly as a Night Refuge; it was formerly the library of Charles I, and was afterwards used for prayer meetings by Oliver Cromwell. It was surrounded by a garden, thence the name of Rose Street, one of the outlets from this quarter. In later days, a market was held here, and the porters used to stand hard by waiting to be hired – and so gave their name to another street. The remembrance was kept up no doubt for some time of the kings and the princes who visited this spot, as the name of Princes’ Row belongs to the houses that surround the Refuge – the poorest, the dirtiest, and the lowest houses that this part of London can boast of, making the prefix “prince” a very mockery to the Row we are speaking of. But the remembrance of princes, of gardens, of poets and of statesmen exists no longer in the minds of the dwellers in these parts. What they know Princes’ Row to be famous for is the gambling that is always going on there amongst the idle and the worthless of the neighbourhood. Stretched on the pavement you may see a small group, some playing, others looking on at games of cards, of marbles, or with stones, those various games wellknown to the street arabs, and which are so numerous, that a different one belongs to each month of the year.

In January what are called shoots are in the hands of most boys – that is an elastic fastened to a frame, with which bits of orange peel and other things can be shot forth to a great distance; and I know well the time when this sport is in vogue by the annoyance it is to me in the night school. Later they have cat-traps, or tip-cats, as they are called, a simple game with two pieces of wood; then there are marbles, tops, buttons, kites, cherry stones; in August grottos, probably in memory of St. James of Compostella; at other times rounders, and gobs, a game played with stones placed on divisions marked out on the pavement, and thrown up into the air and caught as they fall on the back of the hand. In November they buy what are called fireworks, explosive balls, that make a loud noise in falling to the ground. Hoops are used by smaller boys in the winter, as snow-balling is but a rare pleasure for Londoners.

The police will tell you that Princes’ Row is remarkable for having more apprehensions than any other spot of the same size in London. Not only is it a resort for street gamblers, but it is also a favourite rendevous for fights. I have heard of one grand one in the last five years, between the champions of Marylebone and St. Giles, who met there as a convenient battlefield on which to try their relative strength.

And the reason for this choice of Princes’ Row is that round the Refuge there is a broad road and pavement, where carriages and carts seldom pass. No strangers make this road a thoroughfare, – women from the neighbouring streets are afraid of going round Princes’ Row, and policemen do not like to come there alone, as they have often met with rough treatment when endeavouring to stop a fight. There are four outlets from this Row – two of them are merely courts, and when a band wishes to engage the ground for gambling or fighting, scouts are posted at the various entrances, who give timely notice of the approach of the policeman. Often as I have passed by I have seen boys quietly lying on the pavement enjoying their game, and suddenly they have sprung up and disappeared, and it was only after some minutes that I have seen the disturbing element in their slowly advancing enemy. But from both boys and men of this class, whose solace it seems to be to gamble, to swear, to drink, and to fight, who are ill-housed and ill-educated, I have experienced nothing but courtesy and respect. The dwellers of Princes’ Row tell me that the swearing over the games is appalling; but as I pass them, or stand by talking to any one they are silent.

About five years ago I determined to try what I could do with these poor boys; who from their very civility to myself, I felt were open to the refining influence of a woman’s teaching. So in February, 1873, after knowing the neighbourhood for three years, I began a School on Sunday afternoons. I invited four boys to come, these brought others, and from that time to August, I had a varying number of from eight to twenty-five every Sunday. I began the School with a working shoemaker, who lived in the next street, and later I had a postman to help; but he was always called “Squint Eye” by the boys, from a personal defect and he never got much hold over them. The shoemaker’s temper and patience used to be sorely tried: as for mine, I felt it no trial, for the fact of contending with the determined mischief of some of the boys, had in it the delight of a fight, in which I was generally victorious.

I tried to arrange the boys in classes, and taught them reading, writing, and arithmetic. The first year I did not attempt any religious instruction, my chief reason being that they were too unruly and uncivilised, and would only have made an irreverent mocking of such teaching. But in order to show them that there was something to be aimed at beyond mere learning, I ended the lessons with a prayer, when I was able to get them sufficiently quiet to have a reasonable hope that they would behave with reverence during the few minutes the prayer lasted; but more than once as I repeated the Lord’s prayer aloud, I have heard some of the boys parodying it throughout in very blasphemous language.

The moment of dispersion was often the time of revolt. The room we had, was lent to us by the vicar of the parish; in the week it was used for a Ragged School, where some industrial work was taught. It opened out of a passage from the street, the house door being always open. The boards which formed the partition of this passage were not very tightly joined, and cabbage-stalks and winkles picked up from the street were often thrown in through the apertures. Occasionally a boy would come and spit at us through the openings, or make noises that were answered by the boys within, with such powers of ventriloquism that it was impossible to discover the culprit. A step ladder led down from the room we were in to a cellar, used in the week-time for cutting up wood and preparing it in faggots for sale. As I said the moment of trial was the end of the school. As long as I could keep the boys under my eye, they were tolerably well-behaved, and to call to them by name was generally sufficient to restore order; but if, when the prayer was finished, my attention was wanted at the door, and I could no longer keep watch over the ladder, down would they rush, and make hideous confusion with the faggots, – and one day lighted a match and narrowly escaped burning down the house.

The amount of learning the boys got during this first half-year was not much: later we could do more amongst them when the discipline was greater, and several have learned to read who only knew their letters when they first came. But though there was not much learned by the boys, there was education and humanising of many amongst them. For instance, one boy of fifteen, who had attended very well up to June, came then to me, and told me he was leaving for a Baptist Sunday School where the boys behaved better, and he had got the taste for school by coming to us. Six of the boys who began that summer have continued with me till either too old to come any more, or have left the parish and gone to other schools. Later, two of these six boys were confirmed, and two when they were seventeen years of age went to the Working Men’s College, anxious to increase their knowledge.

I have said that I meet with nothing but courtesy and civility from the boys, and some may say the spitting, the throwing cabbage stalks, and the cat-calls were not civilities. True! but they were not directed at me particularly, and arose from a mischievous feeling for fun. One Sunday in June I was out of town, and I left the school in the charge of a young lady and a “Sister.” The boys took advantage of my absence, and spent the whole time in throwing winkles about the room.

In October of this year we began a Night School, in addition to the one on Sunday afternoons, the boys paying a penny for the two evenings. The payment was useful in two ways: it made them value the teaching more, and gave us the power of refusing to admit boys who brought no money with them, when we knew their only object in coming was to make a disturbance. In the week, the staff of teachers consisted of myself, my maid, and a gentleman who had some previous experience of rough boys, and who has from that time carried on the school jointly with myself, both on weekdays and on Sundays. Another teacher came for a few weeks; but he was driven away by the impertinence of these poor roughs. His hair was red, and he had a pointed beard, for which reason the boys called him the Shah, and used to ask him who his barber was. These and other impertinences, which he could neither tolerate nor correct, drove him from the school. After he left, a Scotch gardener came, and was of great use, having a firm and quiet manner by which he could control the boys who were under him, and make the lessons interesting.

We had the advantage of a better schoolroom this year, which was again lent to us by the vicar. It was close to Princes’ Row and Princes’ Court: but though we had no objectionable passage, we were constantly disturbed by knockings at the door from boys whom we had previously expelled, and we were obliged at last to ask the police to allow us to have a constable on duty outside the school whilst we were there in the evening, as there was constant throwing up of stones and rubbish at our windows. Indeed, one day a large stone came through into the schoolroom, but fortunately fell on the floor without striking any one. We had from twenty to thirty boys on Sundays, several never missed; but many came but once or twice to see what it was like. Occasionally an unruly boy would come, and either begin to fight with his neighbour or refuse to do the lesson with the others. I would remonstrate with him at first, and if that had no effect I would get one of the male teachers to turn him out. This was a matter of some difficulty, as we were closely packed, and the boy would often kick and resist. However, during the struggle, there was perfect silence, all the boys would watch intently and a calm seemed to fall on those that remained after one of the number had been expelled. This was the only punishment I could either threaten or inflict. The first expulsion was not final, as I would take them back if they promised to behave well.

In January, 1874, I tried what good could be done for the boys by taking them to an evening Mission Service, at the Refuge, held by the curate in charge of this district. The school finished at 5 o’clock, and I then invited those who liked to remain with me, to listen to a story. I read to them till six, or if they wished to go home to their tea, I asked them to return and to go with me to the service. About a dozen boys generally accompanied me. They behaved very well, and they appeared to enjoy the short service, which consisted of prayers, of singing and a short and simple sermon, – the whole thing lasting little over half-an-hour.

For three months, I continued this practice, and thought that this would have given the boys a taste for attending evening service, but I was rather disheartened on saying to one of them who had been the most regular —“

Now that Easter has come, the services will leave off here, and I hope you will attend some church where you will have the same hymns and prayers you have been hearing during the last three months.” The lad answered me, “No, I do not think it is likely I shall go to any church.”

“Why?” I said. “Because,” was the reply, “I do not believe in the whole thing, in a God or anything else.” And so I discovered he had come only for the sake of pleasing me. This same boy kept on regularly coming to our school till he joined the Working Men’s College. His home was wretched and miserably poor from the drunkenness of his father and the illness of his mother, and the poor boy was broken-hearted at times, and has told me the misery was so great he should like to put an end to himself; and here was an instance where I am sure the constant sympathy and interest felt for him by his teachers helped him to work on, so that now he is in a good position as a musical instrument maker, very dutifully helping the wretched home where he no longer lives.

A year or two ago, I asked him to come and help me to teach in the Night School. He came a few times, and then left off. I rather wondered at his so soon giving up helping me, but I said nothing, as I knew he was hard-worked, and I supposed he found the school too great a toil. However, some years after I found out the reason, and it was this, that in coming out of the school, the other boys would lay wait for him and pelt him with mud and stones. After bearing this ill-treatment for a few weeks, and having his Sunday hat broken, he gave up coming to teach, but did not like to tell me the cause of his doing so.

Another boy we were able to help very materially this year through the work of the school was John Vine. He had been at Feltham, but had left it two years when I first knew him. He was a strong boy, and well-disposed: but he had a drunken mother, who lived with an Irishman, who could work well, but was also generally drunk. The boy’s father a Scotchman, had died some years back, and when I first knew John he was in rags, seldom having any thing like shoes on his feet, but always ready to do any cleaning or sweeping he could get from his neighbours. Notwithstanding his rags, he came regularly to the school, and was well-behaved, and seemed very anxious to work. A friend of mine, hearing my account of the boy, asked to see him, was interested in him, and clothed him, and got him work, which he kept for four years, always behaving himself properly. When unfortunately through differences with his wife, whom he had married at seventeen years of age, he got drunk and lost his place; but there are such ups and downs in the life of the poor that I do not despair of him yet.

On Sundays, the curate who held the Mission Service used to come into the school for half an hour and have a class of boys, consisting of a few who were willing to he taught by him, or whom I could persuade to join the class. Four of these were unbaptised: they all promised to be prepared by the clergyman for that Sacrament, but only one kept his word, – was baptised, and afterwards confirmed, and has turned out a steady, well-behaved boy.

This year we gave the boys three treats. On Christmas Day we gave them a supper, on Easter Monday we took them for a day into the country, and on the Bank holiday in August they had an afternoon tea in a garden near Kensington. All these pleasures helped much to educate them in other ways than book-learning, making them feel that they were cared for by those above them in position, for the sake of whose good opinion they wished to keep respectable.

The discipline of a school depends to a great extent on its locality, and also on the size and suitable arrangement of the school room. And so we improved still more in our discipline, when we moved again from Princes’ Court to Chapel Place in the third year of our school. The reason of this change was that owing to the death of the vicar the school in Princes’ Court was done away with, and we were then allowed the use of one of the large school rooms lately finished and adjoining the church.

We began both the Sunday and Night School in December, and continued them on to August, but found it was a mistake to do so, for in the summer the attendance became very small. In the evenings the boys liked to be out after hot days of work, and on Sundays they would generally go for excursions into the country. It is bad for the discipline of the school to keep it on with a poor attendance, as it makes the boys think they are doing their teachers a kindness in coming, instead of the reverse. Gratitude is not a condition of mind we often meet with, and it is important for the boys to feel that it is themselves who are benefited by coming to school, and not to think that any advantage accrues to the teachers by their attendance.

We had a larger attendance on Sundays than on weekdays, and about half a dozen boys of seventeen, who came very regularly. We had not quite as many bad boys, who only came for mischief, as at the other school. This one was not in a thoroughfare, nor was it a convenient resort for the idle boys who hang about the streets all day. I have had boys at the school whose cropped hair showed me whence they had come. Some disappeared for a time, and I heard of them next at Clerkenwell. Others I have known from the police to be confederates of thieves, and there were a few whose lives were so ill-spent that there was not much hope of improving them. Indeed the conclusion I have come to in this respect is, that we can improve those who are willing to improve themselves, and who wish to be respectable, and to learn; — but by no Sunday or Night School alone can we reform idle and evil boys to any great extent. The school may be the means of bringing them to a knowledge of what is better, and a wish to improve, but to be reformed they must be altogether removed from their bad associations.

One boy, especially, Arthur Anderson, is an example of what I am saying. His father was a respectable carpenter, who from the ill-health of his wife, was in great poverty. The boy had learned no trade and had no regular place, but got any chance work he could find in the neighbourhood. He was sixteen and wished, he said, to go to sea – a profession I always recommend to any boys who seem fitted for it. He got his papers and went up for the medical examination; but unfortunately having bad teeth, he was considered unfit for the navy. The boy was in despair, and said to me that he felt it would be impossible, if he remained where he was, to withstand the bad companions who surrounded him. He asked me to get him on board a merchant vessel, and the longer the voyage, and the further from England he should go, the better pleased he would be. But two things were necessary for this – an expensive outfit, and his teeth being put in order. The first I was able to get for him through the liberality of two of my friends, and the second through a letter to the Dental Hospital, where the boy patiently spent two or three hours for many days whilst a young practitioner was getting through the work, evidently new to him, as he would often leave the boy to ask advice as to how the next operation was to be performed.

The boy sailed to Sydney, and was away two years, during this time he wrote me several happy, grateful letters, and when I saw him on his return he brought me an excellent report from the ship, and was eager to return for the next voyage. He had received on that trip only ten shillings a month, but was promised for the next two pounds a month.

If he had remained at home no doubt he would have gone as he expected to the bad; and often the downfall of a boy seems to be but the result of an accident, or of a misfortune, and once sunk into the slough of wickedness to be found in London I know no human efforts that can drag them out of the mire.

There was a boy, James Jinks, whose fate I much deplored. He had been brought up at St. James’ Workhouse School, and had received a very good education. He was placed on leaving at Chapman and Hall’s, and remained there for six months, obtaining a very good character. He had to leave because he caught scarlet fever, and was taken to a hospital. On coming out, he had no place to go to, no friends, and soon no clothes. He then fell amongst evil companions. I saw him often about this time, and gave him some clothes, after I had inquired of Mr. Chapman if he had given a true account of himself. He did not come near me again for some time, and when he did he said he had been ill. I then said I would try to get him a place; but took the precaution first of sending the shoe-maker teacher to where he lived – such a bad account, however, was brought to me of his way of living, that I did not feel justified in recommending him to any employer. And this poor boy, had he not had the scarlet fever at that unfortunate time of his life, might have kept well through those years of difficulty.

Another boy I had been much interested in, and who had learned to read with us, was John Mac. He had been very troublesome many times, but with constant rebukes and encouragement we had kept him on. One evening I inadvertently left the bag of pennies I received from the boys, on the desk, and it disappeared. I suspected this boy; but only said that the bag had gone. The boy I suspected never came again, and I could well imagine he had taken it.

The discipline was not yet good, and we were much tormented in January, the month dedicated to the game of shoots which I have described. The bits of orange-peel flew about the school, and it was impossible to discover the offender and none would tell of the other. In March the tops were produced, nuts were thrown about, and the ventriloquism that continued was impossible to detect; but by degrees the bad boys left off coming as the discipline became more severe.

The last conflict we had was in 1876; a boy, called Patrick, had come in, whom I knew to be thoroughly bad. However, as he promised to behave well, I let him remain, but he soon showed that his only object was to disturb the others. He made noises, and finally refused to do the lesson I set him. I then told him to leave the class he was in, and to sit elsewhere. This also he refused to do, and whilst I was speaking to him a young guardsman, who was teaching another class, saw the insubordination, and fresh from the discipline of his men came up and offered to turn out the boy. I still tried to parley with Patrick, but with no success; so before he knew what was in store for him, the young officer was behind him, and putting his own arms under those of the very dirty and ragged Patrick, lifted him up and put him clean out of the school at the expense of tremendous kicks on his own shins: this was the last forcible expulsion we had from the school. Boys still came who were very poor, and some who certainly had not sufficient food. One of them told his teacher one cold winter evening how he had slept for three nights in the street, because his father had driven his from home. He was very cold, and was thankful to get a warming from the good fire. I called next day at his home, and from his mother heard that what he had said was true. She did not venture to let the boy in again, as the father, who had been drinking hard, said he would kill him if he returned. I was able to get this boy into St. Andrew’s Home for Working Boys, in Dean Street, to which I have already referred. Here he could earn his own living, and has turned out well.

The following year we put the Night School under Government Inspection, closing in April, after having kept it open fifty-six nights, four boys attending over fifty nights, and many over forty nights in the season. Several different teachers came at various times, and very kindly helped us to teach; but the one who joined me in Princes’ Court was alone responsible with myself in managing the school.

We still had some unruly boys; there was one in particular – George Snow – who was full of fun and talk, and would always have the last word. This boy unfortunately gave our school a bad name for discipline, as he would “chaff” the Government Inspector, and was daunted by nothing; but he was a good boy and never missed an evening, though often kept late at work for a shop in Piccadilly; and when he left it, with a good character of three years, I was able to get him a place as a railway porter, where he has done very well, justifying the recommendation I gave him.

That year, 1875, games were started for the boys on the Wednesdays, and a club on the Saturday nights, the school being held on Tuesdays and Fridays, for which they now paid two-pence a week. The games and club are managed by two gentlemen, and are very largely attended – the nightly average attendance being 140. The charge for admission is the same as at the school – a penny per night. The games were begun as an experiment in the direction of forming Working Lads’ Clubs on the same principle as those of men, the attraction provided being of course different to suit youthful tastes. The experiment has been entirely successful in regard to the number of members, the room being always full to overflowing, and the receipts from the boys have been sufficient to cover all expenses (save rent) including salaries, light, coal, &c. Fencing and boxing, besides quieter amusements of bagatelle, draughts, and dominos, are the principal games, while a coffee and cake bar add to the profit of the club. There is ample scope for giving lectures for the lads, the only hindrance in this way being the lack of personal assistance.

It is plain from the large attendances at this club that there is a great need for places of harmless recreation for the immense working-boy population in London, and the clergy would find extraordinary opportunities of gaining a hold over their boy-parishioners by using their school rooms in the evening in the manner indicated.

We changed the Sunday School into one of purely religious teaching, but the attendances became much less, and it no longer attracted the older boys. Our object has always been to get a hold on boys of from thirteen to eighteen, – that dangerous time in the life of working boys and girls, when their habits are formed for good or for evil, for industry or for idleness. At this time especially are they alive to the influence of those above them; they are capable of affection for their teachers, which will induce them to keep straight. The school has to vie with many pleasures of an attractive nature outside, hence the teaching must be made attractive, the boys must feel an interest in the success of the schools as tested by the Government Inspection. They must feel they are working for a definite object, and that their individual advancement is as much a matter of interest to their teachers as to themselves. The tone you get into a school influences very much all new-corners, and the higher you set the standard the more you will accomplish.

I have always remembered what an experienced School Inspector once said to me about good marks for punctual attendance at school. “If you give them good marks (to the children) for doing their duty, duty will not become to them a rule, a necessity. Give bad marks for unpunctuality, then they will feel that they have done wrong in neglecting the duty, not a meritorious action in fulfilling it.” This principle I have tried to carry out in the Night School. The attendance being a voluntary action on the part of the boys, it was necessary in order to ensure regularity and attention to assume an authority over them, which of course existed only as an idea. Often have I met some of our boys in the street who had lately been missing school, and when I asked them why they had not been they made some excuse, and tacitly admitted my right to demand their attendance.

The following letter will exemplify what I say. I one evening told the writer, a boy of seventeen to write for a composition a letter giving me the reason for his irregular attendance whilst I had been away, and to my surprise he wrote this —

‘MADAM,

“I write you these few lines in ancer to your letter inquiring of me why I have not attended school of late. I must own it was wrong of me to stay away, but since you have been away there are but few who keep order of any kind. I suppose Mr. Bennett is not enough for them, but since you are back again I shall be most happy to return.

“Yours &c.,

With regard to marks and prizes, I think the plan of giving threepence or sixpence to the boy who has done the best exercise in the class, or who has answered best, is very objectionable; it makes them, as I said before, think it a merit if they do well. The system of working in standards, as practised in the schools under Government inspection, is far the best impetus they can have. To all who were qualified by their attendance and good behaviour to be examined by the inspector we gave a framed certificate, recording their standard and number of attendances. These certificates we found were much valued.

The first year we were under Government inspection we presented twenty-four, and the second year twenty-five boys, to these we gave an excursion into the country and other pleasures. By the system of standards a stupid boy of sixteen who has struggled with much difficulty to pass the first standard is as much rewarded as the clever boy of fourteen who gets through his fractions in the sixth standard without any difficulty. The inspection is much looked forward to by the boys, and last year their behaviour was so good that the inspector complimented us on our discipline.

In the first report Mr. Matthew Arnold says, “The neighbourhood is one where an Evening School might do much service. But forty hours to accomplish work for which day-scholars have five hundred hours!” -meaning, by this, how is it possible to advance one standard with merely the work of a Night School. However, we have done so in several cases, as our examination of 1877 will show; and one boy may specially be remarked on, who the first year got to Standard IV., soon after leaving the Day School. Last year he passed successfully in Standard V., and this year he has got through Standard VI. Of course the boy who gains a standard has seldom missed a night, attending forty or fifty times from October to April. Many of them will come straight from work, bringing with them a piece of bread to eat for their supper sooner than lose any time by going home for it; and I have seen some so tired with their long day’s work, that they have dropped to sleep over their lessons. The boys like to find themselves of importance at an inspection, with the knowledge that their progress will be reported on; and much of the orderly behaviour of last year was owing to their hearing the report read, where their want of discipline was mentioned. This gave them the desire to try and deserve a better report.

Several boys have, like the writer of the letter above-mentioned, been deterred from coming through the rude behaviour of the others. This was the case with two Scotch boys, very intelligent and anxious to learn. They left off coming; so I went to inquire the cause, and saw the mother, a respectable, clean Scotchwoman. She was reluctant at first to give me any reason, but on my pressing her said the fact was, that her boys told her that they could not bear to sit quietly by and hear a lady rudely treated. I told her the discipline was improving, and she must tell them I particularly wished them to return, as the presence of orderly boys helped to make the others more orderly. They returned and were constant in their attendance, until they had to leave London with their father. I have lost sight of them now, but perhaps they will turn up again at some future time.

Many boys pass away from our sight. Out of the 120 admittances one year, and 100 the next, we presented, as I said, about twenty-five each year, but as many more came directly under our notice and influence in various way, though they did not make up the number of attendances required by Government. Some left off coming when they had to work overtime; some ceased to care for the school, but even those who were but a short time with us had gained something from contact with teachers who were interested in their welfare. They at least would never later in life have the bitter, though mistaken feeling that exists in the minds of many of the poor, that the rich and well-to-do take no heed of the poor, and that their happiness and interests are not considered.

There are often disappointments in the boys, and those perhaps whom we take most trouble for turn out worst. One boy, James Webb a nice-looking, clean, bright boy, with light curling hair, came very regularly to us one winter. He had no settled place of work, and told us he would much like to go to sea. He had once made a short voyage, and said it was the life he would prefer; his mother, a drinking Irishwoman, sold watercresses, an employment that is considered the lowest amongst hawkers. I went to see her to ask if she was willing the boy should go to sea, she said quite so, as he did not help her at all, so after some trouble we got him engaged by the captain of a small trading vessel, he was started with clothes and many small things that would be useful to him on board ship. He sailed, and I got a letter from him from the dock, before starting, saying how much he liked the ship, and how grateful he was for the help he had received. My mind was easy about him, thinking that an honest seafaring life would set him up in the world, when on day as I was walking down Piccadilly who should I see but James in his sailor’s clothes, taking a good look into a print shop. He started when I spoke to him, but explained his presence there, by the fact that his ship had gone ashore in a fog off the Isle of Wight, and that he had come up to give evidence with reference to the insurance of the ship. Some thing about his manner made me suspicious. I made inquiries; found out that all he had said was untrue, – that he had really left his ship as soon as it touched land, had come to London and was amusing himself about town. When I discovered his misconduct and deceit, I saw him once more, and told him how ill he had behaved. I have never spoken to him since, though I have seen him, and I fear that this attempt to put him straight having failed, placed him in a worse position morally than if nothing had been done for him.

As a general rule, the clothes of a boy will be an index of his good conduct; as there is such a demand for boys’ labour in this part of London, that any industrious, respectable boy can get work and good wages. I was one Sunday saying this to the boys, that I thought less well of them when I saw them in ragged and dirty clothes, and I knew it was generally their own fault. One or two of them said, “Ah! but teachers in other Sunday Schools say they like us better in rags: they do not want us to have good clothes!” On which I answered, that those teachers probably did not know them as I did in school, and out of school, in their homes, and often, alas! idling away many hours outside the public house.

But of all faults the worst to contend with in a boy is idleness. If he will not work, you may give him chance upon chance; you may reprove, you may encourage, nothing will do them good. I have had a few cases of idleness where I have got a boy a place, but his laziness caused him to be discharged. I have come upon boys I knew of seventeen, who instead of working were playing at marbles in courts where they never expected to meet me.

As I have said, the worthless boys have ceased to come to our school. We have a regular attendance, and perfect order and quiet. The boys on entering fall into their proper places – none have to be called to order. When we finish, as we always do with a prayer, there is complete calm. They are all working lads, some are apprentices, some have learned their trades, and some are errand boys. The work of teaching is no longer one of difficulty, the civilising has been done, but much more could still be done if we had more helpers. We could have more religious teaching on Sundays, and more classes on the week days. The boys are now attracted to the school, and as long as it continues to be conducted in the same spirit, more and more boys will come. But the natural consequences of the improved discipline is to attract only the better class of working boys. To meet the rest a school must begin again in the worst neighbourhood, amidst the wild and turbulent spirits. That work is open still to any one who will undertake it, and I should gladly welcome any who would begin it next autumn I am sure they would meet with as good results as we have had.

In time, with the work of the School Board, there will, I hope, be no such thing as boys of fourteen and fifteen coming to us unable to read, but we shall always find boys who have learned to read and write, who, like those we now have, having passed the Fifth Standard, are anxious to come not only to keep up their learning, but to increase it; and we shall find that the school, the games, and the club, will be the best means of preserving the boys from the evils which surround them in great cities.

I have mentioned already instances of the different influences, that various teachers have over the boys, and I think that almost the first element of success in dealing with them is the sympathy that should exist between the teacher and the taught. We have had a marked example of this in the Girls’ Night School held in the same building. It was begun two years ago, and was so successful that last year, the school having been open three nights a week for five months, there was an average attendance of forty girls, from thirteen to twenty years of age. This year the mistresses are changed from various causes, and the members have diminished to an average of nine. At last only six came, and the school is now closed.

Instead of a night school for girls I have now started a sewing class for them once a week; it is for those who have left school and are at work in trades or at home. They readily bring their pennies to pay for the class, and we teach them needlework and cutting out, and great is the delight of these poor girls to be able to go home and show their mothers that they can cut out a shift. The best of mothers could not well teach their girls to cut out in one crowded room which is occupied by the whole family day and night; and nothing contributes more to the comfort of the home of a working man than when his wife can make his shirts and the children’s clothes, instead of buying them ready-made, as many do in London, a cheap article perhaps, but ill-sewn and a poor material.

Whilst the girls work a story can be read to them, or they can join in singing. Work with both boys and girls of this age is deeply interesting, no labour will more repay any person for the time and trouble they may spend upon it.

References to the introduction

Booton, F. (ed.) Studies in Social Education Volume 1: 1860-1890, Hove: Benfield Press. 199 pages. This collection of material includes Sweatman’s paper on youth institutes and clubs, the full text of Maude Stanley’s Clubs for Working Girls (plus this chapter), and Pilkington’s ‘An Eton Playing Field’.

Eagar, W. M. (1953) Making Men. The history of Boys’ Clubs and related movements in Great Britain, London: University of London Press.

Stanley, M. (1878) Work About the Five Dials, London: Macmillan and Co

Stanley, M. (1890) Clubs for Working Girls, London: Macmillan. (Reprinted in F. Booton (ed.) (1985) Studies in Social Education 1860-1890, Hove: Benfield Press.

Steman Jones, G. (1984) Outcast London. A study in relationships between classes in Victorian society. 2e, London: Penguin.

Download the full book from the Internet Archive.

This piece has been reproduced here on the understanding that it is not subject to any copyright restrictions and that it is, and will remain, in the public domain.