The notion of Muscular Christianity was an important feature of some key discourses around work with boys and men in the second half of the nineteenth century. Here Clifford Putney explores the origin and use of the term.

contents: muscular christianity · bibliography · how to cite this article

The phrase “muscular Christianity” probably first appeared in an 1857 English review of Charles Kingsley’s novel Two Years Ago (1857). One year later, the same phrase was used to describe Tom Brown’s School Days, an 1856 novel about life at Rugby by Kingsley’s friend, fellow Englishman Thomas Hughes. Soon the press in general was calling both writers muscular Christians and also applying that label to the genre they inspired: adventure novels replete with high principles and manly Christian heroes.

Hughes and Kingsley were not only novelists; they were also social critics. In their view, asceticism and effeminacy had gravely weakened the Anglican Church. To make that church a suitable handmaiden for British imperialism, Hughes and Kingsley sought to equip it with rugged and manly qualities. They also exported their campaign for more health and manliness in religion to antebellum America, where their ideas failed to catch on immediately due to factors such as Protestant opposition to sports and the popularity of feminine iconography within the mainline Protestant churches.

Opposition to muscular Christianity in America never completely disappeared. But it did weaken in the aftermath of the Civil War, when changes in American society placed health and manliness uppermost in the minds of many male white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. These men, who included Social Gospel leaders such as Josiah Strong and politicians such as Theodore Roosevelt, viewed factors such as urbanization, sedentary office jobs, and non-Protestant immigration as threats not only to their health and manhood but also to their privileged social standing. To maintain that standing, they urged “old stock” Americans to revitalize themselves by embracing a “strenuous life” replete with athleticism and aggressive male behavior. They also called loudly upon their churches to abandon the supposedly enervating tenets of “feminized” Protestantism.

As evidence that there existed a “woman peril” in American Protestant churches, critics such as the pioneer psychologist G. Stanley Hall pointed to the imbalance of women to men in the pews. They also contended that women’s influence in church had led to an overabundance of sentimental hymns, effeminate clergymen and sickly-sweet images of Jesus. These things were repellant to “real men” and boys, averred critics, who argued that males would avoid church until “feminized” Protestantism gave way to muscular Christianity, a strenuous religion for the strenuous life.

The heyday of muscular Christianity in America lasted roughly from 1880 to 1920. During that time, the YMCA invented basketball and volleyball, the Men and Religion Forward Movement sought to fill Protestant churches with men, and the churches took the lead in the organized camping and public playground movements. These efforts to make muscular Christianity an integral part of the churches lasted throughout World War I. But in the pacifistic 1920s, there emerged widespread discontent with many of the ideals that had flourished during World War I, including muscular Christianity. Protestant leaders such as Harry Emerson Fosdick and Sherwood Eddy blamed muscular Christianity for encouraging militarism. And satirists such as H. L. Mencken and Sinclair Lewis skewered muscular Christianity in their writings.

The postwar devaluation of muscular Christianity was evident not only in literature but also in the mainline Protestant churches. By the 1930s, these churches were gravitating toward the Neo-Orthodoxy of Reinhold Niebuhr, who argued that divinity resided not in men’s muscles, but with God. As Neo-Orthodoxy arose in the mainline Protestant churches, muscular Christianity declined there. It did not, however, disappear from the American landscape, since it found some new sponsors. They include the Catholic Church and various rightward leaning Protestant groups. The Catholic Church promotes muscular Christianity in the athletic programs of schools such as Notre Dame, and the evangelical Protestant groups that support muscular Christianity include Promise Keepers, Athletes in Action, and the Fellowship of Christian Athletes.

Bibliography and further reading

Hall, Donald, ed. Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Higgs, Robert. God in the Stadium: Sports and Religion in America. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1995.

Kimmel, Michael. Manhood in America: A Cultural History. New York: Free Press, 1996.

Ladd, Tony, and James Mathisen. Muscular Christianity: Evangelical Protestants and the Development of American Sport. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 1999.

Macleod, David I. Building Character in the American Boy: The Boy Scouts, YMCA and Their Forerunners, 1870-1920. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

Mjagkij, Nina, and Margaret Spratt, eds. Men and Women Adrift: The YMCA and the YWCA in the City. New York: New York University Press, 1997.

Putney, Clifford. Muscular Christianity: Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880-1920. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Vance, Norman. The Sinews of the Spirit: The Ideal of Christian Manliness in Victorian Literature and Religious Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

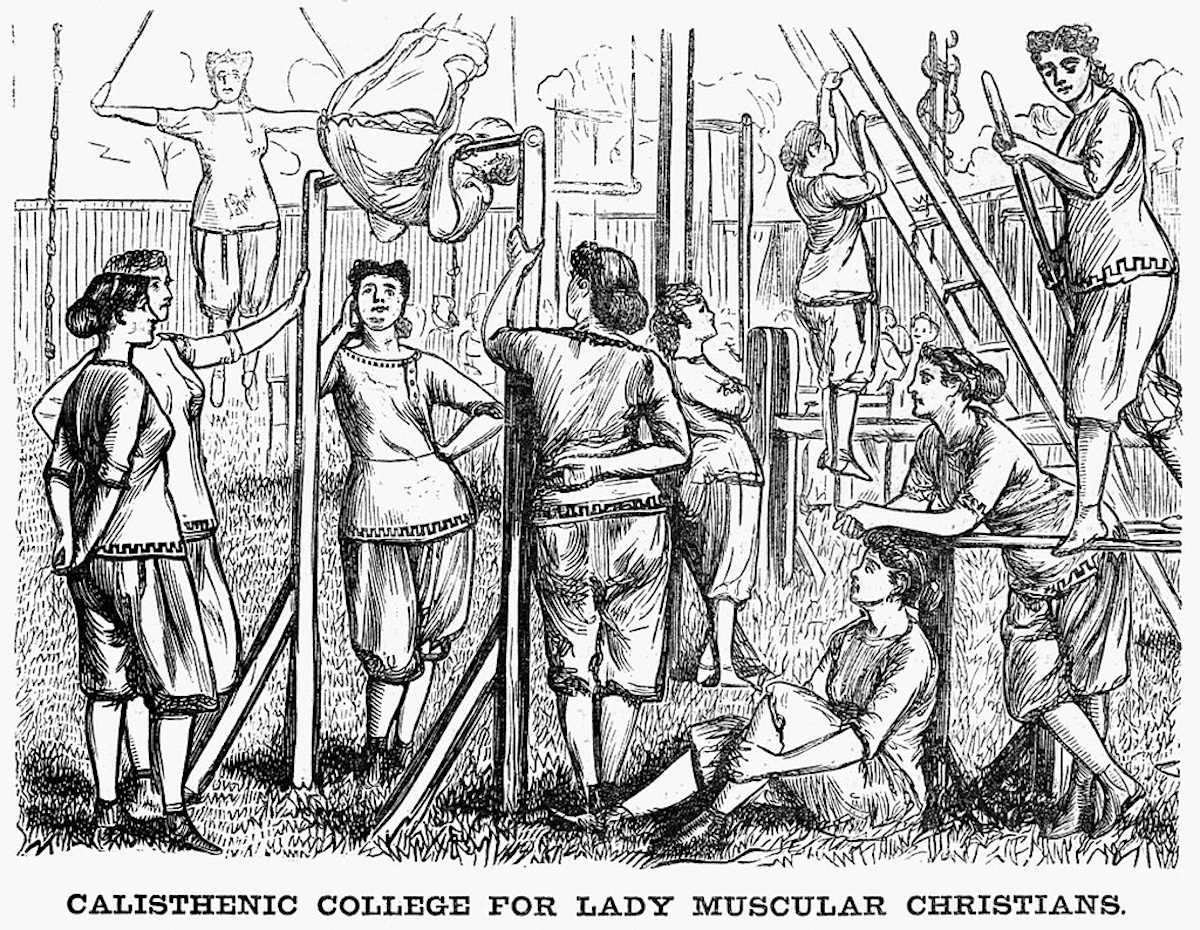

Picture: Calisthenic College for Lady Muscular Christians – Wood engraving 1867. Unknown artist. Currently included in the Granger Collection, it is used here as a cc0, via Wikimedia Commons.

How to cite this article: Putney, C. (2003) ‘Muscular Christianity’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, www.infed.org/christianeducation/muscular_christianity.htm. The article first appeared in ABC-CLIO (2003) Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia.

This article [excerpt] is reproduced by permission of ABC-CLIO, Inc. and appears in Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia © 2003 by ABC-CLIO