Hannah More: Sunday schools, education and youth work. Hannah More was initially famous for her playwriting and involvement in ‘blue stocking’ circles. Later her evangelicalism led her to philanthropy, writing popular religious tracts and then onto pioneering work in Sunday Schools. Here we examine her contribution and her involvement in the development of youth work.

contents: introduction · hannah more – her life and works · sunday schooling · religious tracts and literacy · conclusion · further reading and references · links · how to cite this article

Hannah More (1745-1833) has been recently ‘rediscovered’ as both an early feminist and as an anti-feminist. This focus on her beliefs about gender has led to criticism that has been ‘somewhat flat and one-dimensional’ (Lawless 1999). Hannah More’s philanthropic activities, her theories and practices as an educator, her involvement in pressure group politics, and her contribution to literacy studies are worthy of sustained attention. Patricia Demmers (1996), for example, judges that she was the most influential female philanthropist of her day and Anne Stott (2003) has described her as the ‘first Victorian’

In this article we examine, in particular, her involvement with her sister Martha in the development of Sunday schooling; her contribution via religious tracts to the development of literacy; and her approach more generally to education. It has been claimed by writers like Young and Ashton (1956) and Milson (1979) that Hannah More was one of the central precursors of youth work. We briefly examine this claim and the contribution she made to the development of informal education.

Hannah More – her life and works

Hannah More was born in Stapleton near Bristol in 1745. Her father, Jacob More, was the headmaster of a foundation school there (in Fishponds). She was the fourth of five sisters – all of whom developed strongly individual personalities (Hopkins 1947: 10). She was a ‘delicate’ child, and ‘high-strung, easily stimulated, affectionate, and oversensitive to criticism’ (ibid.: 11). Jacob began to train all his daughters to be teachers from an early age, although he was somewhat ambivalent about such education as he thought that female brains could be wrecked by too much ‘book learning’. Hannah’s quick intelligence alarmed him.

The three older More sisters decided to open a boarding school for ‘young ladies’ and set about establishing it. They were only nineteen, seventeen and fourteen themselves at the start of the venture. Opening in 1758 (at 6 Trinity Street, College Green, Bristol), and funded initially by subscription, the school was a success from the start and its reputation soon spread. Within a short time Hannah and her younger sister Martha joined the staff. Part of the success of the school lay in the knack the sisters had for making and developing contacts and friendships. Their activities also attracted a range of people to them: Charles and John Wesley became friendly with Hannah’s older sister Mary, James Ferguson, the astronomer, and Thomas Sheridan (the father of the playwright) lectured at the school. Edmund Burke was a frequent visitor to the home the sisters established in Park Street, Bristol.

Hannah was a lively, quick witted and charming young woman to the outside world. However, from an early age she withdrew into periods of depression and ‘gave herself up to headaches, colds, bilious attacks and other functional illnesses’ (Hopkins 1947: 31). She met and became engaged to Edward Turner. Some twenty years older than Hannah, he was the owner of a large estate close to Bristol. Turner kept postponing the marriage – it is said that Hannah More’s ‘indifferent temper’ worried him – and in the end an annuity of £200 per year was settled on her as a way of extricating himself from the engagement. Hannah went to Uphill, near Weston-super-Mare to recuperate (she was said to be ‘recovering from an ague’) and it was clear she was in some distress.

Hannah More, playwright

As a result of this experience, it is suggested, Hannah More resolved not to marry. She began calling herself ‘Mrs More’ and set about becoming a ‘woman of letters’ (the annuity gave her the material springboard for this). She had been writing poetry for some time and had written a play for the young women at the sister’s school. Hannah More now turned to the professional stage – and her first effort The Inflexible Captive (later known as Regulus) opened at the Theatre Royal, Bath in 1775. She began a series of annual London visits. On the first Hannah was accompanied by two of her sisters – and they took lodgings in Henrietta Street, Covent Garden. They were introduced to London by Sir Joshua Reynolds and his sister Frances (who was also a portrait painter). Through her theatrical activities, Hannah More had also developed friendships with David Garrick and his wife Eva (and often stayed in their house in the Adelphi), and with literary figures like Dr Johnson.

Further plays followed, including Percy. A tragedy in 1777 (produced at Convent Garden Theatre) and The Fatal Falsehood. After David Garrick’s death in 1779 Hannah stayed with Eva Garrick in the Adelphi house and was involved in the conversation parties of the so-called ‘Blue stocking’ circle. Hannah More’s interests changed. She began to turn against the stage and started to rewrite Bible stories in dialogue form. She also started to lose interest in the sorts of of social relationships that characterized the strata of London life in which she was involved. The deaths of Garrick, her father, and Dr Johnson (and other members of her London circle) ‘saddened her and made Hannah More more susceptible to the influence of deepening friendships with the evangelical men and women of the Clapham Sect and other progressive religious groups’ (Hopkins 1947: 144).

Sunday schooling

The Clapham Sect (so named because many of its members lived close to Clapham and worshipped in the parish church) was an influential, but informal, group of wealthy evangelicals who sought to reinvigorate the Church of England with what could be described as a modified form of Methodism. It’s members included Henry Venn (1725-97), William Wilberforce (1759-1833) and Zachary Macaulay (1768-1838 – father of the historian Thomas Macaulay). They were strongly opposed to slavery (Macaulay, for example, had been appalled at the conditions experienced by slaves while he lived in Jamaica), and committed to missionary work. The Clapham Sect was also involved in the foundation of the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1804.

William Wilberforce, in particular, was to become a very significant influence in Hannah More’s life. They first met in Bath in 1786, and he became a regular visitor to her new cottage at Cowslip Green, Wrington close by the Mendip Hills and later to her house about a mile away at Barley Wood (where Hannah was joined by her sisters). Significantly, it was on one of these visits in 1787 that Wilberforce announced that ‘something had to be done for Cheddar’. He had spent some time in the nearby village and came away resolved that action had to be taken to improve the condition of people there. Besides the poverty he was upset at the lack of spiritual comfort. Out of the discussions that followed the idea emerged that what was needed as a first step was a Sunday school. Two years later Hannah and Martha More opened such a school in Cheddar and in the next ten years or so they set up more than a dozen Sunday schools (see <href=”#sunday_schooling”>below).

While concerned about physical and spiritual poverty, the sisters believed in the existing organization of society. Theirs was no radical project. ‘Beautiful is the order of society’, Hannah wrote, ‘when each according to his place, pays willing honour to his superiors – when servants are prompt to obey their masters, and masters deal kindly with their servants; – when high, low, rich and poor – when landlord and tenant, master workmen, minister and people… sit down satisfied with his own place’ (quoted by Simon 1964: 133). In this we can see that obligation went both ways. Duties were reciprocal (Bebbington 1989: 71). However, it still meant that her ‘plan for instructing the poor’ was ‘very limited and strict’. Hannah More continued, ‘they learn of week-days such coarse works as may fit them for servants. I allow of no writing for the poor. My object is not to teach dogmas and opinions, but to form the lower classes to habits of industry and virtue’ (M. More 1859: 6). The framework for this activity was clear. ‘I know no way of teaching morals’, Hannah More wrote, ‘but by teaching principles, nor of inculcating Christian principles without a good knowledge of scripture’ (quoted by Young and Ashton 1956: 237).

Controversy

Hannah More’s views and activities became the focus of the struggle between the evangelical wing of the Church of England (which looked to Sunday schools and similar activities as a way forward) and a more conservative wing that viewed such ‘Methodist’ activities as dangerous. As the Sunday school movement developed, and Methodists became more organized, the reaction grew in strength. Known as the ‘Blagdon Controversy’ the initial spark was a Monday night meeting for adults associated with the Sunday school established by, and associated with, Hannah and Martha More. The session in question was, in essence, a prayer meeting at which people gave testimony. The local curate became deeply critical. Hannah More was accused of being Methodistic – and the situation became the subject of various letters to the press and more than 20 pamphlets over a period of four years (1800-1804). The temper of the debate rose with Hannah being represented, for example, as the founder of a sect. In the end, More had to close the Blagdon school. The controversy had affected her health and she collapsed. Hopkins (1947: 198) comments that illnesses were Hannah’s rest periods. ‘She went into retreat from the world…. and believed that God sent her poor health to turn her toward Him’.

This continuing interest in, and commitment to, philanthropic activities has to be put in the context of the atmosphere of panic in the aftermath of the French Revolution.

[M]ost men and women of property felt the necessity for putting the houses of the poor in order… The message to be given to the labouring poor was simple, and was summarized by Burke in the famine year of 1795: ‘Patience, labour, sobriety, frugality and religion, should be recommended to them; all the rest is downright fraud’… The sensibility of the Victorian middle class was nurtured in the 1790s by frightened gentry who had seen miners, potters and cutlers reading Rights of Man, and its foster-parents were William Wilberforce and Hannah More. It was in these counter-revolutionary times that the humanitarian tradition became warped beyond recognition. (Thompson 1968: 61)

As Hopkins (1947: 203) has suggested, Hannah More’s view was that it was possible to make the poor physically comfortable by showing them to make better use of what they had, and ‘submissive by teaching them that joy in heaven was the recompense for deprivation on earth’. Alarmed at the growing influence of writers like Tom Paine and William Godwin, and at the prompting of the Bishop of London, she sought to write something that would open people’s eyes to the folly of notions like liberty and equality. The result was her first tract: Village Politics, by Will Chip, a Country Carpenter. The book employed four basic arguments. That:

… the gentry look after the worthy poor; no relation exists between government and want; government is no concern of the common man; God knows what is best for his people. (Hopkins 1947: 208)

This was quickly followed up by her response to Dupont’s speech in the National Convention, Paris in December 1792 making the case for anti-religious public schools: Considerations on religion and public education ; and Brief reflections relative to the emigrant French clergy (1793).

Tracts and other works

The success of Village Politics encouraged More and other members of the Clapham group to produce the Cheap Repository Tracts. These were a series of readable moral tales, uplifting ballads, and collections of readings, prayers and sermons. Hannah More was to write and edit many of the tracts, while other Claphamites raised the money for printing and distribution (the tracts were sold at a little under cost). The first was published in March 1795 – and last some three years later. The tracts were published monthly – and overall sold in the millions (see <href=”#tracts”>below). Over 100 were produced – fifty of them by Hannah More.

As well as the tracts, Hannah More also wrote several more substantial didactic works. Three particular works look at education:

Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education (1799) – which went through 13 editions and sold more than 19000 copies;

Hints for Forming the Character of a Princess (1805) – a far less popular book that was basically designed as a course of study for Princes Charlotte, daughter of the Prince of Wales; and

Colebs in Search of a Wife (1809) – Hannah More’s only novel. The book proved be very popular – selling more than 30,000 copies in the United States, for example, before More’s death.

It is these books that have been a source of considerable debate as to More’s view of women and their role. On the one hand, it can be argued that her view of women’s education was more progressive than many others within the middle classes at the time.

She made many excellent observations on the subject, pointing out that it was unjust to keep women ignorant and scorn them for it, holding that education should be a preparation for life rather than an adornment; she advocated only for exceptional girls the classical education which she and her sisters had received. She would have the average girl trained in whatever ‘inculcates principles, polishes taste, regulates temper, subdues passion, directs the feelings, habituates to reflection, trains to self-denial, and more especially, that which refers to all actions, feelings and tastes, and passions to the love and fear of God’. She would have history taught to show the wickedness of mankind and the guiding hand of God, and geography to indicate how Providence has graciously consulted man’s comfort in suiting vegetation and climate to his needs. (Hopkins 1947: 230)

The countercase is made by looking to the thinking of her contemporary Mary Wollstonecraft. Though she may well have agreed with More that female education was deficient and needs reform, Wollstonecraft proposed a universal literacy that placed ‘importance on the cultivation of reason, without prescribing functional use of education. For Wollstonecraft, education should enlighten individuals without restricting them to particular skills or reading materials (Lawless 1999b). Set against such analysis, it is hardly surprising that More has been found wanting by many recent scholars (For an exploration of this see Demers 1996).

Final years

The More sisters lived together at Barley Wood in the Mendip Hills until the death of Mary in 1813. Theirs had been an extraordinary history – growing up together, working together, living together. The three other sisters died within a few years. By 1819 Hannah was alone. For some years she suffered poor health and she played out a number of deathbed scenes. She was rarely out of her bedroom and the situation at Barley Woods appears to have got out of hand with servants cheating her. Eventually, she was persuaded to move to a house in Windsor Terrace, Clifton – close to friends who could keep an eye on things. Much of her time was spent dealing with the vast volume of correspondence that arose out of people’s encounters with her work. As she recognized death was getting close she began to arrange for the disposal of much of her fortune among various charities and religious societies. She died on September 7, 1833, and was buried with her sisters in Wrington churchyard.

Hannah More and the development of Sunday schooling

Sunday schools emerged in the seventeenth century – but were promoted and championed by Robert Raikes from 1780 on. Their orientation and methodology hit a particular chord – especially within evangelical groups. It is, therefore, not surprising that William Wilberforce and the More sisters should see Sunday schooling as a way forward. At Cheddar [in 1791, Hannah More wrote]:

… we found more than 2,000 people in the parish, almost all very poor—no gentry, a dozen wealthy farmers, bard, brutal and ignorant.. . . We went to every house in the place, and found every house a scene of the greatest vice and ignorance. We saw but one Bible in all the parish, and that was used to prop a flower-pot. No clergyman had resided in it for forty years. One rode over from Wells to preach once each Sunday. No sick were visited, and children were often buried without any funeral service. (from H. Thompson, (1838) Life of Hannah More quoted by Young and Ashton 1956: 237-8)

Wilberforce and More were appalled that this situation had been apparently accepted by local worthies. Hannah More believed a significant, perhaps the key, factor was the lack of religious knowledge among the poor and a lack of moral teaching.

Activities in the newly established school largely fell into two camps – those aimed at children, and those concerned with adolescents and adults. Sunday was chosen as the main teaching day (hence the name of the schools) as it was a time when students and teachers would be free from work and duties. Some classes were also held on weekday evenings – especially for mothers. Reading, knitting and sewing were the main activities. According to Young and Ashton (1956), she did not teach writing and cyphering, ‘maintaining that such accomplishments would breed sedition, and give the lower orders ideas above their station’ (1956: 238). This said, there was significant opposition to their activities from some local farmers, one of whom believed that ‘religion would be the ruin of agriculture’ – and that it introduced much mischief (Hopkins 1947: 164).

Hannah and Martha (Patty) More made several visits to local people (both farming and labouring families) in Cheddar before starting the school seeking support and gathering potential students. They found a house (for the schoolmistress) and barn (for the classroom) and opened the school in October 1789.

At first even the reading was of the Scriptures only, though later she began herself to write stories, homilies and poems with a moral purpose, for she believed as John Wesley did, that it was no use to teach people reading, if all there was to read was the ‘seditious or pornographic literature of commercialism’. The object of the schools was also to make honest and virtuous citizens, and this was furthered by her various savings societies. At each meeting all the members, especially the women, were encouraged to deposit a little, even a penny a week, against the rainy day. This was used as a kind of insurance fund from which a sick contributor was able to draw out 3s. per week, while maternity grants of 7s. 6d. were available. She hoped also to raise the moral standard of the village by refusing membership of her schools to the non-virtuous. Girls found indulging in ‘gross living’ were to be shunned and excluded! (Young and Ashton 1956: 239)

Alongside these schooling activities, Hannah and Martha More also encouraged community schemes. One example was building a village oven for baking bread and puddings (thus saving fuel). They also promoted and administered schools along the Cheddar model in a number of other villages. A large amount of the money to support these schools came from members of the Clapham Sect.

The significance of Hannah and Martha More’s activities concerning Sunday schooling lay in the pedagogy they developed; the range of activities they became involved in; and the extent to which publicity concerning their activities encouraged others to develop initiatives. Hannah and Martha More attempted to make school sessions entertaining and varied. We can see this from the outline of her methods published in Hints on how to run a Sunday School (and reported in Roberts 1834). Programmes had to be planned and suited to the level of the students; there needed to be variety; and classes had to be as entertaining as possible (she advised using singing when energy and attention were waning). She also argued that it was possible to get the best out of children if their affections ‘were engaged by kindness’. Furthermore, she made the case that terror did not pay (Young and Ashton 1956: 239). However, she still believed it was a ‘fundamental error to consider children as innocent beings’ rather than as beings of ‘a corrupt nature and evil dispositions’ (More 1799: 44, quoted by Thompson 1968: 441). She was not above resorting to bribery:

I encourage them [she said] by little bribes of a penny a chapter to get by heart certain fundamental parts of Scripture…. Those who attend four Sundays without intermission receive a penny. Once in every six to eight weeks I give a little gingerbread. Once a year I distribute little books according to merit. Those who deserve most get a Bible. Second-rate merit gets a Prayer-book—the rest, cheap Repository tracts. (quoted in Young and Ashton 1956: 239)

This mix of methods, and the somewhat questionable orientation around children’s nature, did find an echo among many other evangelicals. When combined with the efforts of Robert Raikes and the formation, in 1785, of a non-denominational national organization, the Sunday School Society, to co-ordinate and develop the work we find some key elements of the basis for the amazing growth of Sunday schooling in the nineteenth century.

Hannah More, religious tracts and literacy

Kenneth Levine has argued that around the period that Hannah More was active, there were significant shifts in the working class. In particular, he suggests, it:

… separated into elements that assimilated ‘respectable’ cultural forms in school, work and worship, and those that embraced ‘subterranean’ traditions of autonomy, community solidarity and political dissent. At one, more institutionalized, pole lay the schools founded by the British and Foreign, National, and the various infant societies, the Sunday schools and the factory schools. To greater or lesser degrees, these offered literacy embedded in syllabuses and regimes intended to inculcate piety, discipline and obedience, as these virtues were perceived by the predominantly middle-class sponsors and organizers. At the more informal pole lay the private venture schools, the corresponding societies, the ale and coffee reading rooms, self-help and casual instruction from parents and friends, whole in an ambiguous middle zone lay institutions like mechanics’ institutes. (1986: 87)

Having looked to more formal avenues to educating the working and labouring classes, Hannah More now turned to what she saw as the dangers associated with the other pole identified by Levine. As we have already seen she was alarmed by the rise and widespread readership of radical writers like Tom Paine. The Rights of Man had sold in its thousands – and it, and books like it, helped to create a political consciousness ‘among novitiate readers’ (Levine 1986: 89). Hannah More’s first attempt to counter Paine’s influence was the tract Village Politics (More 1792) – and it was followed by the monthly series: Cheap Repository Tracts (1795-98). These tracts ‘imitated the lively style, and also the format, of the popular chapbooks or broadsheets’ (Kelly 1970: 78). Later she explained her involvement in such writing:

… as an appetite for reading… had been increasing among the inferior ranks in this country, it was judged expedient, at this critical period, to supply such wholesome aliment as might give a new direction to their taste, and abate their relish for those corrupt and inflammatory publications which the consequences of the French Revolution have been so fatally pouring in on us. (More 1801 quoted by Kelly 1970: 78)

Hannah More while not embracing the call for universal literacy, did recognize the importance of what might be called ‘popular functional literacy’. She also recognized a place for women (although not, as we have seen, in quite the terms we might expect today). Lawless (1999b) has argued that More’s language, ‘which stresses agency and value, elevates women’s status from passive objects to contributing members of society’. She continues, ‘though More works within the restrictive system of functional literacy that does not seek to liberate women from oppression, her moral, utilitarian educational approach ascribes agency and importance to women’.

Conclusion

Hannah More was one of the best-known philanthropists of her day. Her development of Sunday schooling with her sister Martha; her employment of popular tracts; and her broader literary activities mark her as an important figure. She was one of the first women to achieve this sort of visibility via this root. As Bebbington (1989: 26) has commented, ‘In an age when avenues into any sphere outside the home were being closed, Christian zeal brought them into prominence’. Hannah More’s evangelicalism, like others in her group, took the form of individualist Christianity

… which allied faith hope and charity to national purpose… Though narrow in its theology and often conservative in its politics, evangelicalism was wide in its sympathies. This ‘vital religion’ was intensely emotional and left its adherents obsessed with human depravity and the ideal of Christian perfection, whose very elusiveness animated conduct. (Prochaska 1988: 22)

Hannah More could be said to have summed up the prevailing Evangelical attitude when she wrote: ‘Action is the life of virtue, and the world is the theatre of action’ (More 1808, quoted by Bebbington 1989: 12).

Other women like Ellen Ranyard and Maude Stanley were to follow in her footsteps – but just what are to make of Hannah More’s contribution to the development of different forms of informal education – especially youth work?

First, it can be argued that she worked with young people – but significantly they were only one part of the clientele she was concerned with. Hannah More was also interested in the education of children and adults – and both her writing and her activities in Sunday schooling reflect this. To this extent, she can be understood as a theorist and practitioner of lifelong education and learning. Second, she and her sister worked with people on the basis of choice. While there were all sorts of incentives for children and young people, for example, to attend Sunday schooling, Hannah More recognized that they could not be compelled to take part. Third, relative to the schooling activities of her day, Sunday schools associated with the More sisters had a more informal air and used a range of methods. There was more of a concern with creating the right atmosphere and relationship for learning. Besides classes, there were other community and welfare interventions plus some concern with social life (and this was to be a feature of later Sunday school developments). This said the work that Hannah More was engaged in was some distance from what we later came to know as youth work. In particular, hers is an individualistic orientation. There is little recognition here of the significance of association, group and club – and her understanding of education is very firmly conditioned by her desire to convert.

Hannah More remains a controversial figure. Her achievements were formidable, and her attitudes were paternalistic – but she was nevertheless an innovator and one of the first of a whole line of evangelical women philanthropists who were to change the shape of social welfare in Britain.

Further reading and references

Collingwood, J. & Collingwood, M. (1990) Hannah More, Oxford: Lion.

Demmers, P. (1996) The World of Hannah More, University of Kentucky Press. 192 pages. Examines more recent debates about More’s view on gender questions and argues for an appreciation of the full breadth of her work.

Hopkins, M. A. (1947) Hannah More and her circle, London: Longmans. 274 + xv pages. Highly readable survey of Hannah More’s life and achievements.

Jones, M. G. (1952; 1968) Hannah More, Greenwood Press, New York.

Stott, A. (2003) Hannah More. The First Victorian. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 380 + xxviii pages. This book undermines many of the stereotypes associated with Hannah More and reinforces the understanding of her as a complex and contradictory figure: ‘a conservative who was accused of political and religious subversion and an ostensible anti-feminist who opened up new opportunities for female activism’.

References

Altick, R. D. (1957) The English Common Reader: A social history of the mass reading public 1800-1900, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bebbington, D. W. (1989) Evangelicalism in Modern Britain. A history from the 1730s to the 1980s, London: Routledge.

Kelly, T. (1970) A History of Adult Education in Great Britain, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Lawless, A. (1999a) ‘The Status of More Scholarship: Hannah More, Gender, and Literacy’, http://www.personal.psu.edu/users/a/s/asl141/hannahmore/scholarship.html. Accessed June 7, 2002. (No longer available)

Lawless, A. (1999b) ‘Hannah More, Mary Wollstonecroft and the politics of education’, http://www.personal.psu.edu/users/a/s/asl141/hannahmore/politics.html Accessed June 8, 2002. (No longer available)

Levine, K. (1986) The Social Context of Literacy, London: Open University Press.

Milson, F. (1979) Coming of Age, Leicester: National Youth Agency.

More, Hannah (1791, 1808) An Estimate of the Religion of the Fashionable World, London: printed for T. Cadell.

More, Hannah (1792) Village Politics, by Will Chip, a Country Carpenter, London: F. and C. Rivington.

More, Hannah (1793) Considerations on religion and public education ; and Brief reflections relative to the emigrant French clergy, London: T. Cadell.

More, Hannah (1798) Cheap repository (Cheap repository tracts, moral and religious tracts, by Hannah More and her friends, originally published in 1795-1798), London : Sold by J. Marshall, printer to the Cheap Repository for Religious and Moral Tracts

More, Hannah (1799) Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education; with a View of the Principles and Conduct Prevalent Among Women of Rank and Fortune, London: Printed for T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies. (1990 edn. Oxford: Woodstock Books). Selections from this work are available on-line at the WORP archive: http://www.cwrl.utexas.edu/~worp/more/index.html

More, Hannah (1805) Hints for Forming the Character of a Princess, London: Printed for T. Cadell and W. Davies.

More, Hannah (1809) Coelebs in Search of a Wife: Comprehending Observations on Domestic Habits and Manners, Religion, and Morals, (1995 edn. Bristol : Thoemmes Press, 1995).

More, Hannah (1813) Christian Morals, London : Printed for T. Cadell and W. Davies.

More, Martha (1859) Mendip Annals, London: J. Nisbet and Co.

Myers, S. H. (1990) The Bluestocking Circle: Women, Friendship, and the Life of the Mind in Eighteenth-Century England, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Prochaska, F. (1988) The Voluntary Impulse. Philanthropy in modern Britain, London: Faber and Faber.

Roberts, W. (1834) Memoirs of Life of Hannah More (2 volumes), London.

Simon, B. (1964) The Two Nations and the Educational Structure 1780-1870, London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Thompson, E. P. (1968) The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Young, A. F. and Ashton, E. T. (1956) British Social Work in the Nineteenth Century, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul

Links

Hannah More: some important writings by More digitalized for a Women of the Romantic Period collection.

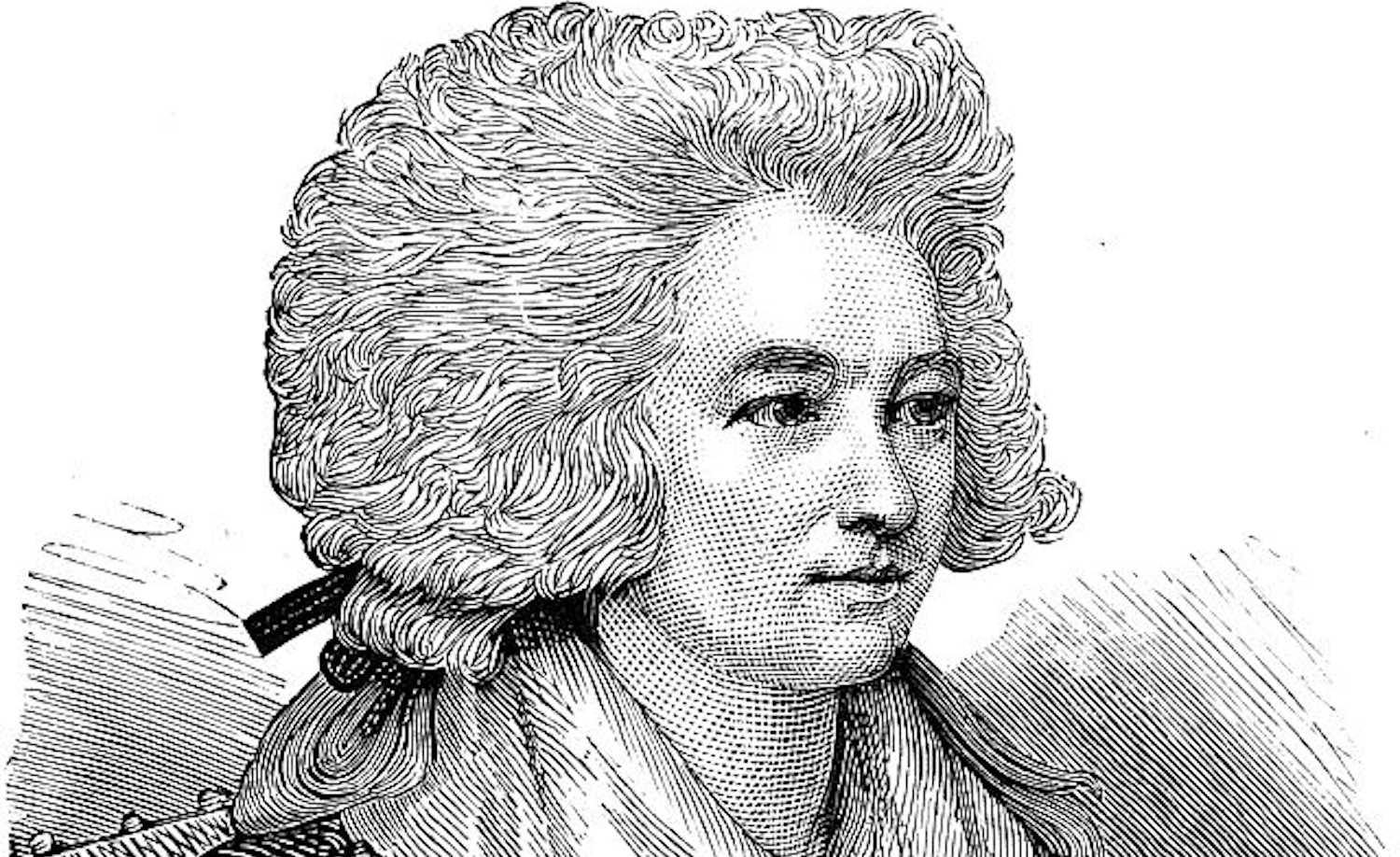

Acknowledgement: The picture of Hannah More is from Wikimedia Commons. The image is by unknown engravers, and thus is PD due to age, per the relevant British legislation.

To cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2002). ‘Hannah More: Sunday schools, education and youth work’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education.[https://infed.org/dir/hannah-more-sunday-schools-education-and-youth-work/. Retrieved: insert date]

© Mark K. Smith 2002

updated: August 18, 2025