This article by Octavia Hill, included in Homes of the London Poor (1883), outlines her case for the need for all people to be able to access space: places to sit in, places to play in, places to stroll in, and places to spend a day in.

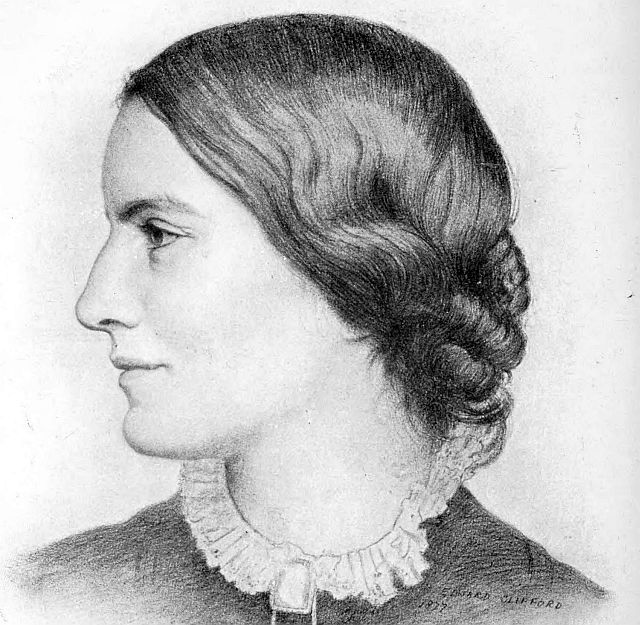

Octavia Hill (1838-1912) is remembered, chiefly, for her innovations in housing and for her championship and organizing around the need for playgrounds and other public open space. She was a formidable campaigner and organizer and was centrally involved in the establishment of the National Trust. She also developed an approach to the management and provision of housing that was highly influential – and played a part in the massive expansion of public housing in Britain between the two world wars.

This piece both illustrates her writing style and reveals some of her key concerns around the provision of public space.

For an account of Octavia Hill’s life and an exploration of her achievements see: Octavia Hill: housing, space and social reform.

_______________

There is perhaps no need of the poor of London which more prominently forces itself on the notice of anyone working among them than that of space.

When I am in their rooms, I feel often how much even a foot or two would be worth, if the room were only large enough to let the wife open the window without climbing on the bed, or if she could get further away from the hot fire on a June day, or if everyone who came in wasn’t forced to brush against the wall so that a great black mark quickly showed itself on the newly distempered surface.

I go into the back-yards, and how I long to pull down the flat blank wall darkening the small rooms, or to push it back and leave a little space for drying clothes, for a small wash-house, for the harrow to stand; and when I look at the unused bits of ground around a farm or cottage, I sometimes think what they would be worth at the back of a London house.

But even in the front of their houses in a London court are the poor much better off? I go sometimes on a hot summer evening into a narrow paved court, with houses on each side. The sun has heated them all day, till it has driven nearly every inmate out of doors. Those who are not at the public-house are standing or sitting on their door-steps, quarrelsome, hot, dirty; the children are crawling or sitting on the hard hot stones till every corner of the place looks alive, and it seems as if I must step on them, do what I would, if I am to walk up the court at all. Everyone looks in everyone else’s way, the place echoes with words not of the gentlest.

In fact it is on such evenings that the drinking is wildest, the fighting fiercest, and the language most violent. A friend of mine at the East of London once said to me, “The winter does not try us half as much as the summer; in the summer the people drink more, live more in public, and there is more vice.” Sometimes on such a hot summer evening in such a court when I am trying to calm excited women shouting their execrable language at one another, I have looked up suddenly and seen one of those bright gleams of light the summer sun sends out just before he sets, catching the top of a red chimney-pot, and beautiful there, though too directly above their heads for the crowd below to notice it much. But to me it brings sad thought of the fair and quiet places far away, where it is falling softly on tree, and hill, and cloud, and I feel as if that quiet, that beauty, that space, would be more powerful to calm the wild excess about me than all my frantic striving with it—Lowell’s words come into my mind,

God’s passionless reformers—

Influences that purify, and heal, and are not seen.

The words reproach my own passionate efforts at reform, and set me asking myself whether we cannot find remedies more thorough, and supply in some measure the healing gift of space.

It is strange to think it must be a gift recovered for Londoners with such difficulty. To most men it is an inheritance to which they are born, and which they accept straight from God as they do the earth they tread on, and light and air, its companion gifts. In one way this fact makes the problem easier to deal with. This space it seems is a common gift to man, a thing he is not specially bound to provide for himself and his family; where it is not easily inherited it seems to me it may be given by the state, the city, the millionaire, without danger of destroying the individual’s power and habit of energetic self-help. The house is an individual possession, and should be worked for, but the park or the common which a man shares with his neighbours, which descends as a common inheritance from generation to generation, surely this may be given without pauperising.

How can it best be given? And what is it precisely which should be given? I think we want four things. Places to sit in, places to play in, places to stroll in, and places to spend a day in. As to the last named, I will not dwell on it here. The preservation of Wimbledon and Epping shows that the need is increasingly recognised. But a visit to Wimbledon, Epping, or Windsor means for the workman not only the cost of the journey but the loss of a whole day’s wages; we want, besides, places where the long summer evenings or the Saturday afternoon may be enjoyed without effort or expense.

First, then, as to places to sit in. These should be very near the homes of the poor, and might be really very small, so that they were pretty and bright, but they ought to be well distributed and abundant. The most easily available places would be our disused churchyards. I have myself no fear that the holy dead, or those who loved them, would mind the living sharing in some small degree their quiet. There is a small, square, green churchyard in Drury Lane, and even the sight of its fresh bright verdure through the railings is a blessing; but if the gates could be opened on a hot summer evening, and seats placed there for the people, I am sure the dwellers about Drury Lane would be all the better for it. Again, round St. Giles’s Church there is space for many seats under the trees. The number of people to be seen in Leicester Square (since the garden was thrown open to the public) show how glad people are of a seat in the open air. But Leicester Square shows us also another thing: such places must be made bright, pretty, and neat—a small place which is not so becomes painfully dreary, and it is quite curious to notice how little one feels shut in when the barriers are lovely, or contain beautiful things which the eye can rest on. The small inclosed leads which too often bound the view of a back dining-room in London oppress one like the walls of a prison; but a tiny cloistered court of the same size will give a sense of repose; and colour introduced into such inclosed spaces will give them such beauty as shall prevent one from fretting against the boundaries. Strange and beautiful instance this of how—if we recognise the limitations appointed for us, accept them, and deal well with what is given—the passionate longing for more is taken away and a great peace hallows all. Let, then, our small open spaces look well cared for. If they are not large enough to be opened to the public without limit, open them under restrictions, lend the key to district visitors, to the schoolmistress, to the clergyman, to the biblewoman, let them take in small companies of the poorest by turns. But make the most of what small spaces you have; do not close them wholly because you cannot open them wholly.

Secondly, the children want playgrounds. I am glad the Board Schools are providing these, and I wish they would arrange to have them rendered available after school hours, and on the Saturday holiday. So far as I know, this is not done. If it were, children would not be obliged to play in alleys and in the street, learning their lessons of evil, in great danger of accident, and without proper space or appliances for games. Such playgrounds, however, must be supervised. Mr. Ruskin provided one nine years ago in one of the courts of which I have charge, and we found then, and have found since, that it was necessary to have someone to keep order, and that it was a great gain to have ladies who would teach the children to play at games; but the whole subject is so admirably explained in the Sanitary Record for July 25th, 1874, that I need do no more than refer to it here; but it may be useful to add that supervision need not be costly. If a man of respectable character, too old to compete with younger workmen, were employed to take care of such a playground, it would be a double charity, such as many a kind donor might be willing to grant.

And, thirdly, we come to the places to stroll in. We could not have a better instance than the Embankment. What a boon it has been to London! Of course the parks come under this head; and to what thousands of people they give pleasure ! But beyond these thousands are many who never find their way to these open spaces. Many notice the numbers who go to them; a few of us know the numbers who do not go. Brought up in dirt, close quarters, and the excitement of the Street tragedies; ashamed of their neglected clothes; shy of a neatly-dressed public, they burrow in courts and alleys out of sight, when they might avail themselves of Park and Embankment. What the Ladies’ Sanitary Association did by their park parties for the children, ought to be done for them also. They must be invited to come out in little companies for a walk, taken out again, and again, and again during the summer. In one of the worst courts under my care we have a small institute for the women and elder girls, where they have classes, and a common sitting-room, and entertainments in winter; but I do believe one of the best things the Institute has done has been to arrange expeditions every Saturday during the summer, to park, or field, or common. The members pay all expenses themselves, and therefore they want places which they can reach by walking, or for a very cheap fare. I only refer to this as a specimen of the kind of thing that will become more and more frequent because it meets a great want —that of happy outdoor amusement, within short distance of their homes, for those who have no gardens, no back-yards— rarely a second room.

There are a few fields just north of this parish of Marylebone which indeed first put it into my head to write this article, though the thoughts contained in it have long been before me. These fields have been our constant resort for years: they are within an easy walk for most of us, and a twopenny train takes the less vigorous within a few yards of the little white gate by which they are entered. They are the nearest fields on our side of London; and there on a summer Sunday or Saturday evening you might see hundreds of working people, who have walked up there from the populous and very poor neighbourhood of Lisson Grove and Portland Town. Fathers, with a little girl by each hand, the mother with the baby, sturdy little boys and merry little girls—as they entered the small, white gate, you might see them spread over the green open space like a stream that has just escaped from between rocks. They sit down on the grass; the baby grabs at the daisies, the tiny children toddle about, or tumble on the soft grass, the mother’s arms are rested, and there she sits till it is time to return; or perhaps they go on up to Hampstead Heath, to which these fields lead, which many could not reach, if these acres were covered with villas, instead of affording a welcome rest. Acres of villas! Yes, at last, the fields will be built over, if they cannot be saved. They are now like a green hilly peninsula or headland, stretching out into the sea of houses; the nearest fields I know to London anywhere; certainly the nearest on our side. The houses have crept round their feet, and left them till now for us. I knew them many years ago, when I used to walk out of London alone; and since then I have been there, as I say, with dozens of parties of the poor. There the May still grows; there thousands of buttercups crown the slope with gold: there, best of all, as you ascend, the hill lifts you out of London, and will always lift you out of it, even when houses are built all round for far away the view stretches over blue distances to the ridge where Windsor stands. As you come home—yes, as your children’s children come home —if you will save the fields from being built over now, will be seen from them the great sun going down, with all his clouds about him, or the fair space of cloudless summer sky, London lying hushed below you—even London hushed for you for a few minutes, so far it lies beneath—though you will be in it in a short ten minutes.

These fields may be bought now, or they may be built over: which is it to be? The owner has given those who would like to keep the fields open time to see if they can raise the money to purchase them for the people for ever. He offers liberal terms, but they will still cost a great deal. Necessarily, fields near London must cost much. The question is, are they worth buying? To my mind they are even now worth very much; but they will be more and more valuable every year—valuable in the deepest sense of the word; health-giving, joy-inspiring, peace-bringing. But they will not be bought without considerable effort. Hampstead, which is on their north, cares comparatively little for them, having the heath on the further countryward side, though such fields between her and London must be a gain. No doubt Hampstead will do something; St. John’s Wood will probably do more, because these fields are to her, as to us, the nearest country walk. Marylebone ought, I think, to help a great deal, if she realises what a blessing those fields are; but I doubt if all three districts can or should do all. I feel myself as if the question ought, in a measure, to be taken up by the large London landowners. They can, even when they try most, give their tenants so small a portion of space—the value of land in any central position being so enormous—that if they were asked for a few yards they would pause; if for large open spaces, they would say, “It is impossible.” The squares they have let to the rich, who will not now in some cases even lend them one Saturday afternoon at the end of the season to the poor of their own district for a flower-show, though if the grass were trampled quite brown, which is the only harm that could be done, another week would find the rich residents in the country among almost measureless green fields and glades. Some of these evils are perhaps unavoidable, but the possession of the land is a very great responsibility, and if there be so very little land on their own estates which they can dedicate to the service of the poor, surely they might feel it incumbent on them to do the next best thing, that is, to secure and throw open such fields as lie nearest to London on any side. The same duty appears to me to lie before the Corporation and the City Companies, and the more because the poor, having been a good deal driven out, the funds left for their benefit from the City, which these bodies have inherited, might well be applied to such an object as this. The Metropolitan Board of Works has, I understand, done a good deal in keeping and buying open spaces, but yet more is needed, I believe, and perhaps they may see their way to help.

It is a bad thing trying to see other people’s duties: they alone can judge what they are. I can only hope that various people will take the question into consideration. I don’t know absolutely that the fields of which I have written are the cheapest to be had, nor that there may not be others nearer to dense centres of population. I happen to know the special beauties of these, and their value to our side of London, and to be personally very fond of them, which somewhat disqualifies me from judging of their relative value. I would not, therefore, plead for these fields in contradistinction to others, though they have their special beauty. What I wish to urge—and I have only introduced a practical example now vividly in my own mind as most strongly bringing home the fact—is, the immense value to the education and reformation of our poorest people of some space near their homes, or within reasonable distance of them. We all need space; unless we have it we cannot reach that sense of quiet in which whispers of better things come to us gently. Our lives in London are over-crowded, over-excited, over-strained. This is true of all classes; we all want quiet; we all want beauty for the refreshment of our souls. Sometimes we think of it as a luxury, but when God made the world, He made it very beautiful, and meant that we should live amongst its beauties, and that they should speak peace to us in our daily lives.

Acknowledgement: The picture of Octavia Hill is from a Drawing by Edward Clifford, 1877. Sourced from Wikimedia Commons this illustration is said to be in the public domain because it was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1923.

Reproduced from: Hill, Octavia (1883) Homes of the London Poor. New edition. London: Macmillan and Co. First published in 1875.

This piece has been reproduced here on the understanding that it is not subject to any copyright restrictions, and that it is, and will remain, in the public domain.