contents: · introduction · the meaning of democracy and the meaning of education · John Dewey, democracy and education · A. S. Neill on democratic schooling · · further reading and references

One of the major tasks that education must perform in a democratic society, Kelly (1995: 101) argues, ‘is the proper preparation of young citizens for the roles and responsibilities they must be ready to take on when they reach maturity’. Others put the case that this is the aim of education:

We can conclude that ‘political education’ – the cultivation

of the virtues, knowledge and skills necessary for political participation – has

moral primacy over other purposes of public education in a democratic society.

Political education prepares citizens to participate in consciously reproducing

their society, and conscious social reproduction is the ideal not only of

democratic education but also of democratic politics. (Gutmann 1987: 287)

For many of the ancient Greeks, such participation was a good in itself. Their term for the private individual was idiotes (idiot). Such a person was, literally, a fool as she or he was not interested in public affairs. This grew out in part out of a recognition that humans are social beings. We are what we are because of our interactions with others. We achieve what we do because we benefit from their work. Thus, if we are all to flourish then we must:

Recognize that we share many common interests.

Commit ourselves to consider those interests (and hence the needs of others)

when looking to our own.

Actively engage with, and seek to strengthen, those situations and movements

that embody democratic values and draw people together. (Jeffs and Smith 1999:

38)

In this view, we do not simply add together individuals and get society. People’s lives are woven together, we share in a common life. As Dewey (1916: 87) saw it, ‘A democracy is more than a form of government: it is primarily a mode of associated living, a conjoint communicated experience’.

Beyond being a good in itself, we can also make a case for democracy on instrumental grounds – on the goods that flow from it. In particular, we can focus on the freedoms, rights and material benefits it affords (Dahl 1998: 44-61) – and the social capital it generates. These come in significant part through the educative and welfare impact of the associational life, relationships and networks linked to it.

We also need to recognize that it isn’t just children and the young who need to prepare for political participation. Political education is necessary throughout life. It isn’t just that many people miss out on a proper political education in their younger years – situations change, new understandings are generated, and it is necessary to explore what these might mean. In this respect the rather narrow concern with skilling that runs through a lot of recent talk of lifelong learning and the

learning society is rather sad.

The meaning of democracy and the meaning of education

Just how we are to approach democracy is a matter of considerable debate. Different understandings imply contrasting educational practices. Carr and Hartnett (1996: 43-45) provide us with a useful illustration in this respect. They contrast a ‘classical’ conception of democracy (in which democracy is seen as a form of popular power) and a ‘contemporary’ conception where democracy is viewed as a representative system of political decision-making.

Classical and contemporary models compared (after Carr and Hartnett 1996)

| Classical (direct) democracy | Contemporary (representative) democracy | |

| View of democracy | Grounded in a way of life in which all can develop their qualities and capacities. It envisages a society that itself is intrinsically educative and in which political socialization is a distinctively educative process. Democracy is a moral ideal requiring expanding opportunities for direct participation. | Results from, and reflects, the political requirements of a modern market economy. Democracy is a way of choosing political leaders involving, for example, regular elections, representative government and an independent judiciary. |

| The primary aim of education | To initiate individuals into the values, attitudes and modes of behaviour appropriate to active participation in democratic institutions. | To offer a minority an education appropriate to future political leaders; the majority an education fitted to their primary social role as producers, workers and consumers. |

| Curriculum content | There is a focus on liberal education, a curriculum which fosters forms of critical and explanatory knowledge that allow people to interrogate social norms and to reflect critically on dominant institutions and practices. | Mass education will focus on the world of work and upon those attitudes and skills, and that knowledge that have some market value. |

| Typical educational processes | Participatory practices that cultivate the skills and attitudes that democratic deliberation require. | Pedagogical relationships will tend to be authoritarian and competition will, as in society generally, play an essential role. |

| School organization | Schools are viewed as communities in which the problems of communal life are resolved through collective deliberation and a shared concern for the common good. | Schools are organized around a pyramidal structure with the head at its apex. |

A model such as this involve caricatures but the contrasts drawn can help us to approach questions around the direction and purposes of education – and its relation to democratic practices. To some extent the distinctions mirror other familiar dichotomies e.g. between andragogy and pedagogy, and ‘romantic’ and ‘classical’ forms of education (Lawton 1975 – although his ‘classical’ position looks more like the contemporary approach above). Indeed, there is some cross-over (not unexpected as someone like Rousseau has been associated to the so-called romantic position and can be linked to many of the concerns associated with direct democracy). However, the starting point and aim of education in these forms does take us along a somewhat different path.

As well as curriculum content, these contrasting models also involve some very different ideas as to how the curriculum is made. The focus on deliberation and practical wisdom in the classical model will tend to link to process and praxis approaches to curriculum. The concern with skilling in the contemporary model will lead people toward more outcome-focused models.

We can also link these models to debates around the meaning of community. The classical model may well link to appreciations that emphasize personal networks and relationships, association and communion; the contemporary model to a view of community as place (territory) and as marketized networks.

John Dewey and education for democracy

In terms of the development of thinking about education for democracy in the twentieth century, it is the figure of John Dewey that towers above all. His is the most significant (certainly the best read) contribution to thinking about education and democracy. He approached education as part of a broader project that encompassed an exploration of the nature of experience, of knowledge, of society, and of ethics. As such, he offers us ‘the ideal bridge from theories of knowledge, to democratic theory and onwards to education theory’ (Kelly 1995: 87). However, consideration of his educational thinking has tended to be isolated from his social and political philosophy (Carr and Hartnett 1996: 54) – so it is with his conception of democracy that we begin.

On democracy. Dewey recognized that many of the then current critiques of democracy, especially with regard to electorate’s lack of knowledge, and the distance between the ideals of the classical model and the reality of government had considerable merit. As Ryan (1995: 25) put it:

[T]he problem was to make democracy in practice what it had

the potential of being: not just as a political system in which governments

elected by majority vote made such decisions as they could, but a society

permeated by a certain kind of character, by mutual regard of all citizens for

all other citizens, and by an ambition to make society both a greater unity and

one that reflected the full diversity of its members’ talents and aptitudes.

Dewey argued for the revitalization of public democratic life. Like Habermas in later times, he placed a great emphasis upon the role of communication in this. ‘Communication is the process of sharing experience till it becomes a social possession’ (Dewey 1916: 9). Through conversation about individual and group wishes, needs and prospective actions, it is possible to discover common interests and to explore the consequences of possible actions. ‘This is what generates “social consciousness” or “general will” and creates the ability to act on collective goals. (Sehr 1997: 58). The process of deliberation and communication over collective goals is what Dewey (1927) viewed as a democratic public.

The development of democracy was an expansion of sociability. The democratic community was in effect the community that best realized the very nature of sociability. Moral growth this involved the acquisition of a capacity for communal life as well as personal fulfillment; we become more fully who we are as we become more able to offer ourselves to others. (Ryan 1998 :407)

A key feature of Dewey’s argument was his concern for ‘social intelligence’ (or social consciousness). Through its cultivation human beings began to develop ‘the capacity collectively to enlarge their own freedom and to create a more desirable form of social life’ (Carr and Hartnett 1996: 59).

On education. In My Pegagogic Creed Dewey held, amongst other things, that:

Education is the fundamental method of social progress.

Education is a regulation of the process of coming to share in

the social consciousness; and that the adjustment of individual activity on the

basis of this social consciousness is the only sure method of social

reconstruction.Education must be conceived as a continuing reconstruction of

experience; that the process and the goal of education are one and the same

thing.This conception has due regard for both the individualistic

and socialistic ideals. It is duly individual because it recognizes the

formation of a certain character as the only genuine basis of right living. It

is socialistic because it recognizes that this right character is not to be

formed by merely individual precept, example or exhortation, but rather by the

influence of a certain form of institutional or community life upon the

individual and that the social organism through the school, may determine

ethical results.The community’s duty to education is, therefore its paramount

moral duty.

If we follow this line of thinking through we can see that people learn democracy by being members of a group or community that acts democratically. In other words, it is through communication and participating in the process of deliberation that we learn to view ourselves as social beings with a concern for the common good, and responsibilities to others. As Dewey (1916: 6) put it, ‘the very process of living together educates’.

| John Dewey on ‘the democratic conception in education Since education is a social process, and there are many kinds of societies, a criterion for educational criticism and construction implies a particular social ideal. The two points selected by which to measure the worth of a form of social life are the extent in which the interests of a group are shared by its members, and the fullness and freedom with which it interacts with other groups. An undesirable society, in other words, is one which internally and externally sets up barriers to free intercourse and communication of experience. A society which makes provision for participation in its good of all its members on equal terms and which secures flexible readjustment of its institutions through the interaction of the different forms of associated life is in so far democratic. Such a society must have a type of education which gives individuals a personal interest in social relationships and control, and the habits of the mind which secure social changes without introducing disorder. Dewey 1916: 99 |

This has profound implications for the way we approach schooling (or indeed any other form of education). The school must be ‘primarily a mode of associated living, a conjoint communicated experience’ (Dewey 1916: 87). Dewey argued that much of education failed because it neglected the fundamental principle of the school as a form of community life.

It conceives that school as a place where certain information is to be given, where certain lessons are to be learned, or where certain habits are to be formed. The value of these is conceived as lying largely in the remote future, the child must do these things for the sake of something else he is to do; they are mere preparations. As a result they do not become part of the life experience of the child and so are not truly educative. (Dewey 1897, reproduced in Dewey 1940: 8)

Conceiving the school as a community in which communication and deliberation flourishes inevitably leads us to consider the nature of relationships between student and student, students and teachers, and teacher and teacher. As Winch and Gingell (1999) note, if schools exist to promote democratic values it would appear that they need to remove authoritarian relationships. ‘Education for democracy thus becomes education freed from authoritarian relationships’ (op cit).

A. S. Neill and participative education

Dewey was writing as a philosopher rather than drawing upon sustained experience as a practicing educator. It is helpful to turn to another significant twentieth century educator A. S. Neill (1883 – 1973). As Jean-François Saffange (1994) notes, when he died at the age of 90 he had spent most of his life in the classroom – as a pupil, pupil-teacher, teacher and headmaster. One of his most significant contributions to educational thinking was to bring insights from psychoanalytical traditions into education. He initially looked to Freud, but was later associated with Wilhelm Reich. However, educationally it was the work of Homer Lane that provided him a model of practice.

Homer Lane (1875-1925) was Superintendent of the Little Commonwealth, a co-educational community in Dorset run for children and young people ranging from a few months to 19 years. Those over 13 years old were there because they were categorize as delinquent. An American by birth, he had early experience as an educator at the George Junior Republic. At the Little Commonwealth from 1913 to 1918 (at Evershot, Dorset) he pioneered what later we came to know as ‘group therapy’ and ‘shared responsibility’. His educational approach involved ‘the path of freedom instead of imposed authority, of self-expression instead of a pouring-in of knowledge, of evoking and exploiting the child’s natural sense of wonder and curiosity instead of a repetitious hammering home of dull facts’ (Wills 1964: 20). Unfortunately, his work in Dorset came to a rather abrupt end after two of the young female ‘citizens’ claimed that Lane ‘had immoral relations with them’ (Wills 1964: 163). As well as having an interest in offenders and expressive forms of education, Lane also worked as a psychotherapist (this also brought him into legal trouble).

| A. S. Neill on Summerhill What is Summerhill like? Well, for one thing, lessons are optional. Children can go to them or stay away from them – for years if they want to. There is a timetable – but only for the teachers. The children have classes usually according to their age, but sometimes according to their interests. We have no new methods of teaching, because we do not consider that teaching in itself matters very much. Whether a school has or has not a special method for teaching long division is of no significance, for long division is of no importance except to those who want to learn it. And the child who wants to learn long division will learn it no matter how it is taught…. Strangers to this idea of freedom will be wondering what sort of madhouse it is where children play all day if they want to. Many an adult says, ‘If I had been to a school like that, I’d never have done a thing’. Others say, ‘Such children will feel themselves heavily handicapped when they have to compete against children who have been made to learn…. My staff and I have a hearty hatred of all examinations. To us, the university exams are an anathema. But we cannot refuse to teach children the required subjects. Obviously as long as the exams are in existence, they are our master…. Summerhill is possibly the happiest school in the world. We have no truants and seldom a case of homesickness. We very rarely have fights… I seldom hear a child cry, because children who are free have much less hate to express than children who are downtrodden. Hate breeds hate, and love breeds love. Love means approving of children, and that is essential in any school. You can’t be on the side of children if you punish them and storm at them. Summerhill is a school in which the child knows he is approved of. A. S. Neill 1968: 20-23 |

A. S. Neill was both impressed by the Little Commonwealth and with his experience of psychotherapy under Lane. He described him as ‘the most influential factor in my life’ (Neill 1972: 135). Summerhill, the school with which Neill is forever associated was founded by him in 1924. As can be seen from the extract, lessons were optional, students can play if they want, do handicrafts, hang about. Afternoons were completely free for everyone. At five various activities began for those that want to take part. The evenings were also used for various entertainments. If it had not been for the threat of the school being closed by the authorities, Saffange (1994: 219) comments, Neill would have placed no ban on sexual relations.

One of the innovations that Neill took from the Little Commonwealth, was the general meeting in which the vote of staff had no greater weight than that of students.

Summerhill is a self-governing school, democratic in form.

Everything connected with social, or group life, including punishment for social

offences, is settled by vote at the Saturday night General School Meeting.Each member of the teaching staff and each child, regardless

of his age, has one vote. My vote carries the same weight as that of a

seven-year-old….Summerhill self-government has no bureaucracy. There is a

different chairman at each meeting, appointed by the previous chairman, and the

secretary’s job is voluntary. Bedtime officers are seldom in office for more

than a few weeks.Our democracy makes laws – good ones too…. The success of the

meeting depends largely on whether the chairman is weak or strong, for to keep

order among 45 vigorous children is no easy task. The chairman has power to fine

noisy citizens. Under a weak chairman, the fines are much too frequent. (Neill

1968: 54)

The School was small enough for everyone to attend if they wished. Some matters of school policy were not discussed by the General Meeting e.g. bedroom arrangements, payment of school bills, and the appointment and dismissal of teachers. However, ‘the regulation of bullying, of cases of stealing, of inconsiderate behaviour’ did come under the care of the Meeting (Stewart 1968: 296). As might be expected the same subjects tend to reappear – behaviour at bed-time and overnight; taking and interfering with private property; damage (ibid: 297). Neill (1968: 59) claims that self-government works. ‘You cannot have freedom unless children feel completely free to govern their own social life. Where there is a boss, there is no real freedom’.

This approach to democratic education has the virtue of looking to the school as a community, and of looking to the possibilities of associationalism. Dewey, would no doubt argue that it entails a retreat from the curricula responsibilities of the educator. The social background of the students and the concerns of their parents, this was after all a fee-paying school that people chose, may well have allowed some freedom around study that could not reproduced in other settings. It may well also be that the approach’s success depends upon having someone like Neill at its heart – a less spirited and able educator would not provide the presence and strength needed to help ‘contain’ the situation and to stimulate experiment. (Much as Buber argues that communities need a ‘builder’ at their heart). But, as Stewart (1968: 299) suggests, it would have been very difficult to get the evidence needed to assess the effect and effectiveness of a Summerhill education (and even more difficult to compare it with other schools). However, there is no doubting that Neill was able to create a place where students felt cared for and respected. He also in his own way, and despite himself, ‘rehabilitated the educator, that controversial character on the educational scene, which the fierce individualism of our time has struck out of the educational treatises, as if needed to be proved that educational success depends largely on the personality of the teachers, their enthusiasm and commitment.

… to be added to.

Further reading and references

Carr, W. and Hartnett, A. (1996) Education and the Struggle for Democracy. The politics of educational ideas, Buckingham: Open University Press. 233 + xii pages. Useful collection of essays that detail developments in England and Wales. Includes a very helpful chapter on democratic theory and democratic education.

Follett, M. P. (1923) The New State. Group organization the solution of popular government, New York: Longmans, Green and Co. 373 + xxix pages. Influential exploration of ‘the group principle’, traditional democracy and group organization. The appendix ‘training for the new democracy’ is a classic statement of community education ideas. Follett was involved in the development of community centers (schools) around Boston – and her resulting proposals and ideas were a significant influence on the pioneers of the community centre movement in the UK.

Frazer, E. (1999) The Problems of Communitarian Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 279 + ix pages.

Giroux, H. A. (1989) Schooling for Democracy. Critical pedagogy in the modern age, New York: Routledge. Very helpful collection of essays that examine schooling, citizenship and the struggle for democracy.

Gutmann, A. (1987) Democratic Education, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. 321 + xii pages. Constructs a theory of education that places the fostering of democracy at its core. Chapters examine the nature of the state; the purposes of primary education; democratic participation; limits of democratic authority; extramural education; educating adults; and the primacy of political education. Pretty much the current liberal standard treatment of the subject.

Held, D. (1995) Democracy and the Global Order. From the modern sate to cosmopolitan governance, Cambridge: Polity. 324 + xii pages. The first, introductory, section provides an overview of different models of democracy. Part two looks to the formation and displacement of the modern state. Part three examines the ‘foundations of democracy’; and the final part attempts a ‘reconstruction’ of democracy around the notion of a cosmopolitan order. See also Held’s (1987) heplful student text, Models of Democracy, Ca mbridge: Polity.

Hernández, A. (1997) Pedagogy, Democracy and Feminism. Rethinking the public sphere, New York: SUNY Press. 123 + xiii pages. ISBN 0-7914-3170-3. £10.00. Hernández constructs a ‘feminist pedagogy of difference’ for cultural workers. She draws upon her experience with the Argentine Mother’s Movement to explore the place of critical pedagogy in the struggle for democracy. Chapters explore the remapping of pedagogical boundaries; informing pedagogical practices (democracy and the language of the public); inhabiting a split (feminism, counterpublic spheres, and the problematic of the private-public); recreating counterpublic spheres; and taking a position within discourse.

Kelly, A. V. (1995) Education and Democracy. Principles and practices, London: Paul Chapman. 202 +xviii pages. Covers some of the same ground as Gutmann but from a later English perspective (e.g. with some consideration of post modernism etc.). The first part of the book examines the fundamental pri nciples of democratic living; part two, democracy and the problem of knowledge; and part three, democracy and education. Clear and committed treatment.

Lakoff, S. (1996) Democracy. History, theory, practice, Boulder, Colarado: Westview Press. 388 pages. Substantial and well written introduction to ‘democracy’. The opening section examines the current appeal of the idea, and democracy as the quest for autonomy. Section two runs through the history with discussions of Athenian democracy (communalism); Roman and later republicanism (pluralism); liberal democracy (individual autonomy) and modern autocracy. The third, ‘theory’ section looks at modern notions of democracy; the individual and the group, and federalism. Section four, ‘practice’ examines democratization, autonomy against itself and democracy and world peace.

Nemerowicz, G. and Rosi, E. (1997) Education for Leadership and Social Responsibility, London: Falmer Press. 166 + xiv pages.Part one of the book looks at different theoretical approaches to constructing an education for inclusive leadership and social repsonsibility. The writers draw from diverse sources here – learning about leadership from children, the world of work, and artists. Part two explores the practice of building educational communities for leadership and social responsibility. Here there is a focus on the campus. Chapters deal with planning and implementing programmes; teachers as leaders; curriculum and co-curriculum; research, assessment and dissemination; and building collaborative communities.The book is the outcome of a fairly large study.

Putnam, R. D. (1999) Bowling Alone. The collapse and revival of American community, New York: Simon and Schuster. 540 pages. Groundbreaking book that marshals evidence from an array of empirical and theoretical sources. Putnam argues there has been a decline in ‘social capital’ in the USA. He charts a drop in associational activity and a growing distance from neighbours, friends and family. Crucially he explores some of the possibilities that exist for rebuilding social capital. A modern classic.

Sehr, D. T. (1997) Education for Public Policy, New York: SUNY Press. 195 + x pages. ISBN 0-7914-3168-1. This book explores two competing traditions of American democracy and citizenship: a dominant, privately-oriented citizenship tradition and an alternative tradition of public citizenship. David Sehr then goes on to explore how the second tradition can be promoted within schooling (in case material from two democratic alternative urban high schools.

Acknowledgements:

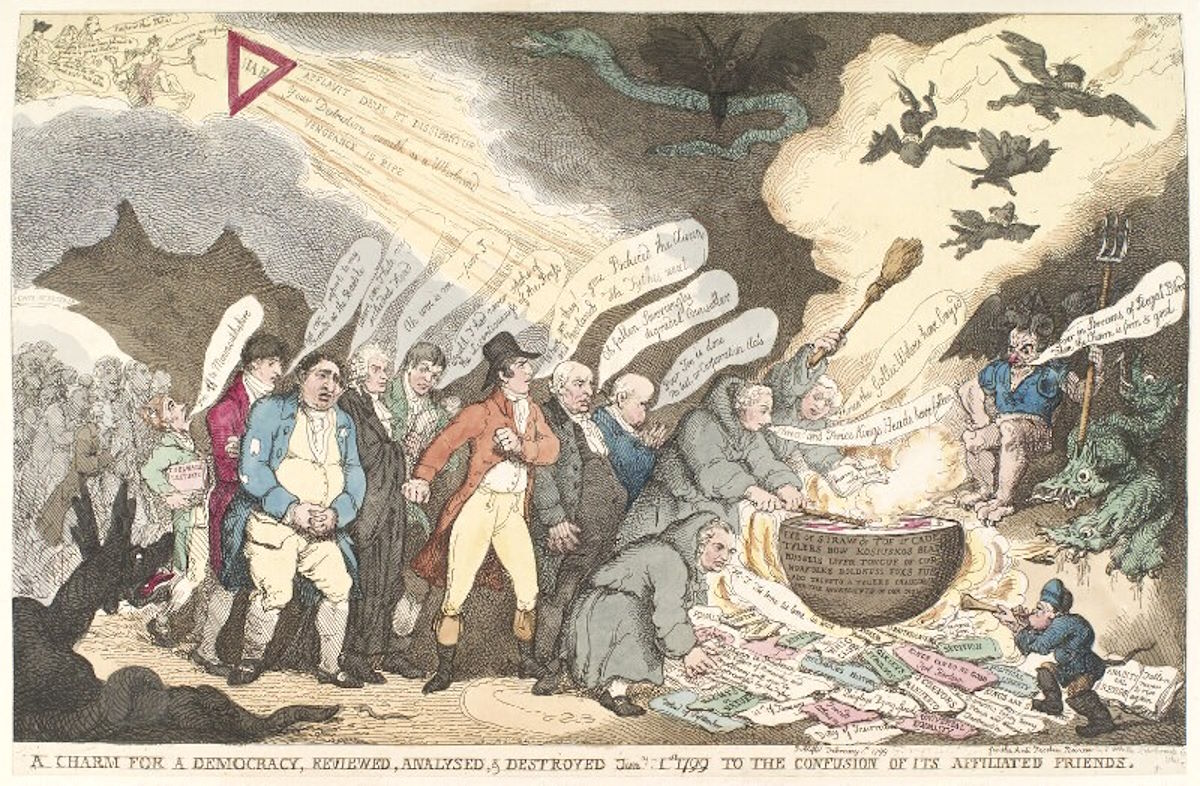

‘A charm for a democracy, reviewed, analysed, & destroyed Jany 1st 1799 to the confusion of its affiliated friends’, by Thomas Rowlandson, published by James Whittle, hand-coloured etching, published 1 February 1799 NPG D12677. Used with the permission of the National Portrait Gallery – ccbyncnd3 licence.

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2001). Education for democracy, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/education-for-democracy/. Retrieved: Insert date].

© Mark K. Smith 2001