Aristotle on knowledge. Aristotle’s very influential three-fold classification of disciplines as theoretical, productive or practical remains an excellent starting point for exploring different forms of knowledge.

Contents: introduction · the theoretical · the productive · the practical · further reading and references · links · how to cite this piece

Aristotle, along with many other classical Greek thinkers, believed that the appropriateness of any particular form of knowledge depends on the telos, or purpose, it serves. In brief:

The purpose of a theoretical discipline is the pursuit of truth through contemplation; its telos is the attainment of knowledge for its own sake. The purpose of the productive sciences is to make something; their telos is the production of some artifact. The practical disciplines are those sciences which deal with ethical and political life; their telos is practical wisdom and knowledge. (Carr & Kemmis 1986: 32)

This way of separating different areas of knowledge can be seen, for example, in the way that we might view ‘pure maths’ (theoretical), tool-making (productive), and social work training (practical). Thus, how we see knowledge and the purpose it serves has a profound effect on the way we view education. It leads to differing understandings of curriculum content and method.

The theoretical: pursuing truth for its own sake

The form of thinking appropriate to theoretical activities, according to Aristotle, was contemplative. It involves mulling over facts and ideas that the person already possesses. This is how one writer describes it:

The Aristotelian contemplator is a man who has already acquired knowledge; and what he is contemplating is precisely this knowledge already present in his mind… the contemplator is engaged in the orderly inspection of truths which he already possesses; his task consists in bringing forward from the recesses of his mind, and arranging them fittingly in the full light of consciousness. (Barnes 1976: 38)

This for Aristotle was the highest form of human activity. It was the ultimate intellectual virtue: a life of unbroken contemplation being something divine. This image can bring to mind pictures of holy men and women reflecting on some eternal truth or of people meditating. The whole thing has a slightly unworldly feel. However, this not a particularly accurate reflection of Aristotle’s thinking. The life of the contemplator was not to be a life of physical denial. Nor was it a matter of letting the mind roam at random. The good person, or expert human, in his view was an ‘ace rationalist’ (Barnes 1976: 37). Actions were to be based on sound reasoning or detailed reflection.

The role of the educators is, presumably, to help people to gain the knowledge on which they are to reflect; to train them in the disciplines of contemplation; and to develop their character so that they became disposed to this form of activity. ‘Intellectual virtue owes both its inception and growth chiefly to instruction, and for this reason needs time and experience’ (Aristotle 1976: 91). Education involves training people from childhood to ‘like and dislike the proper things’. But there is also something more here. Aristotle places this discipline on a pedestal. It is, for him, the highest form of human activity. Educators, if they are to follow this line, must place the gaining of knowledge for its own sake above, for example, the cultivation of affection and sympathy for other people. This is something that many of us would disagree with. As Barnes comments, human excellence runs in a broader and more amiable stream than Aristotle imagined. The fulfilled person will be a lover of others and an admirer of beauty as well as a contemplator of truth: ‘a friend and an aesthete as well as a thinker’ (Barnes 1976: 42).

The productive: making things

If the form of thinking associated with theoretical activities was contemplative, the kind of knowledge and enquiry involved in productive disciplines was a ‘making’ action or poietike. Aristotle associated this form of thinking and doing with the work of craftspeople or artisans. Thus, the making action is not simply seen as mechanical, but also as involving some creativity in an artistic sense. (Interestingly the English word ‘poetry’ is derived from the Greek poietike.) This making action is dependent upon the exercising of skill (what the Greeks called techne) and it always results from the idea, image or pattern of what the artisan wants to make. In other words the worker has a guiding plan or idea. For example, potters will have an idea of the article they want to make. While working, they may make some alterations, develop an idea and so on. But they are restricted in this by their original plan. There is a finite range of options. We can view this process as follows (adapted from Grundy 1987: 24):

exhibit 1: the productive |

|

| People begin with a plan or design; an idea of the object they want to make. | eidos |

| Their frame of mind is that of the artisan or craftsperson as is disposed to use of skills. | techne |

| Together these provide the basis for action – the ‘making action’. | poietike |

| The outcome is a thing or object. | product |

This form of reasoning is very instrumental. It is dominated by the plan or design and actions are thus directed towards the given end. As Grundy comments:

The eidos can only come into being through the techne (skill) of the practitioner, but, in turn, it is the eidos which prescribes the nature of the product, not the artisan’s skill. The outcome of poietike (making action) is, thus, some product. This does not mean that the product will always replicate the eidos. The artisan’s skill may be deficient or chance factors may be at work. The product will be judged, however, according to the extent to which it ‘measures up’ to the image implicit in the guiding eidos. (Grundy (1987: 24)

Put in terms of discussions of process and product, this approach can be seen to be focused around the latter.

The practical: making judgments

The third form of enquiry is what might be called the ‘practical sciences’. These were originally associated with ethical and political life. Their purpose was the cultivation of wisdom and knowledge. They involve the making of judgments and human interaction. The form of reasoning associated with the practical sciences is praxis or informed and committed action. This is a term that many educators encounter through the work of Paulo Freire and has been given a number of different political meanings, particularly within Marxist traditions of thinking. To understand what we mean by it here it is useful to reflect on what we have already said about the theoretical and the productive, and to think about these in relation to what we mean by ‘practice’.

Practice is often portrayed at a very simple level as the act of doing something. It is frequently depicted in contrast to something called theory – abstract ideas about some particular thing or phenomenon. Theory is what you learn in college and then apply to the situations you find in your work. The result is practice. People often talk about professional knowledge as if it were based on theory from which can be derived general principles (or rules). These in turn can be applied to the problems of practice. In this way theory is ‘real’ knowledge while practice is the application of that knowledge to solve problems (hence the phrase ‘applied social science’). This implies that the practitioner is in a sense always a passive implementor, since ends are pre-given and means decided by the theorist. At best practitioners are skilled artisans implementing the ‘design’ of others. We can see in this what we have already been examining: the elevating of theory, and use of a technical disposition – the productive sciences.

Theory and practice are not opposites or separate entities. ‘Practice’ cannot be lacking theory. Similarly, it is difficult to conceive of ‘theory’ that is purely descriptive and devoid of reference to purposeful action. In other words, practice is soaked in theory. It is a constant process of theory making, and theory testing. Thus, it is in this sense that we can begin to talk about practice as praxis – informed action. As Freire put it ‘we find two dimensions, reflection and action, in such radical interaction that if one is sacrificed – even in part – the other immediately suffers’ (1972: 60).

Perhaps the best way of approaching practical reasoning is to look at the starting point. Where the productive began with a plan or design, the practical cannot have such a concrete starting point. What we begin with is a question or situation. We then start to think about this situation in the light of our understanding of what is good or what makes for human flourishing. Thus, for Aristotle, praxis is guided by a moral disposition to act truly and rightly; a concern to further human well being and the good life. This is what the Greeks called phronesis and requires an understanding of other people. We can represent this as follows (adapted from Grundy 1987: 64):

exhibit 2:the practical |

|

| People begin with a situation or question which they consider in relation to what they think makes for human flourishing. | the good |

| They are guided by a moral disposition to act truly and rightly. | phronesis |

| This enables them to engage with the situation as committed thinkers and actors. | praxis |

| The outcome is a process. | interaction |

In praxis there can be no prior knowledge of the right means by which we realize the end in a particular situation. For the end itself is only concretely specified in deliberating about the means appropriate to a particular situation (Grundy 1987: 147). These two statements capture something of the fluidity of the process. As we think about what we want to achieve, we alter the way we might achieve that. As we think about the way we might go about something, we change what we might aim at. There is a continual interplay between ends and means. In just the same way there is a continual interplay between thought and action. What this process involves is a round of interpretation, understanding and application. It is something we engage in as human beings and it is directed at other human beings.

Further reading and references

Carr, W. & Kemmis, S. (1986) Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research, Lewes: Falmer Press. Includes a very helpful overview of Aristotle’s view of knowledge.

Grundy, S. (1987) Curriculum: Product or Praxis, Lewes: Falmer. 209 + ix pages. Good discussion of the nature of curriculum from a critical perspective. Grundy starts from Habermas’ theorisation of knowledge and human interest and makes use of Aristotle to develop a models of curriculum around product, process and praxis.

References

Aristotle (1976) The Nicomachean Ethics (‘Ethics’), Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Barnes, J. (1976) ‘Introduction’ to Aristotle The Nicomachean Ethics (‘Ethics’), Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Freire, P. (1972) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Links

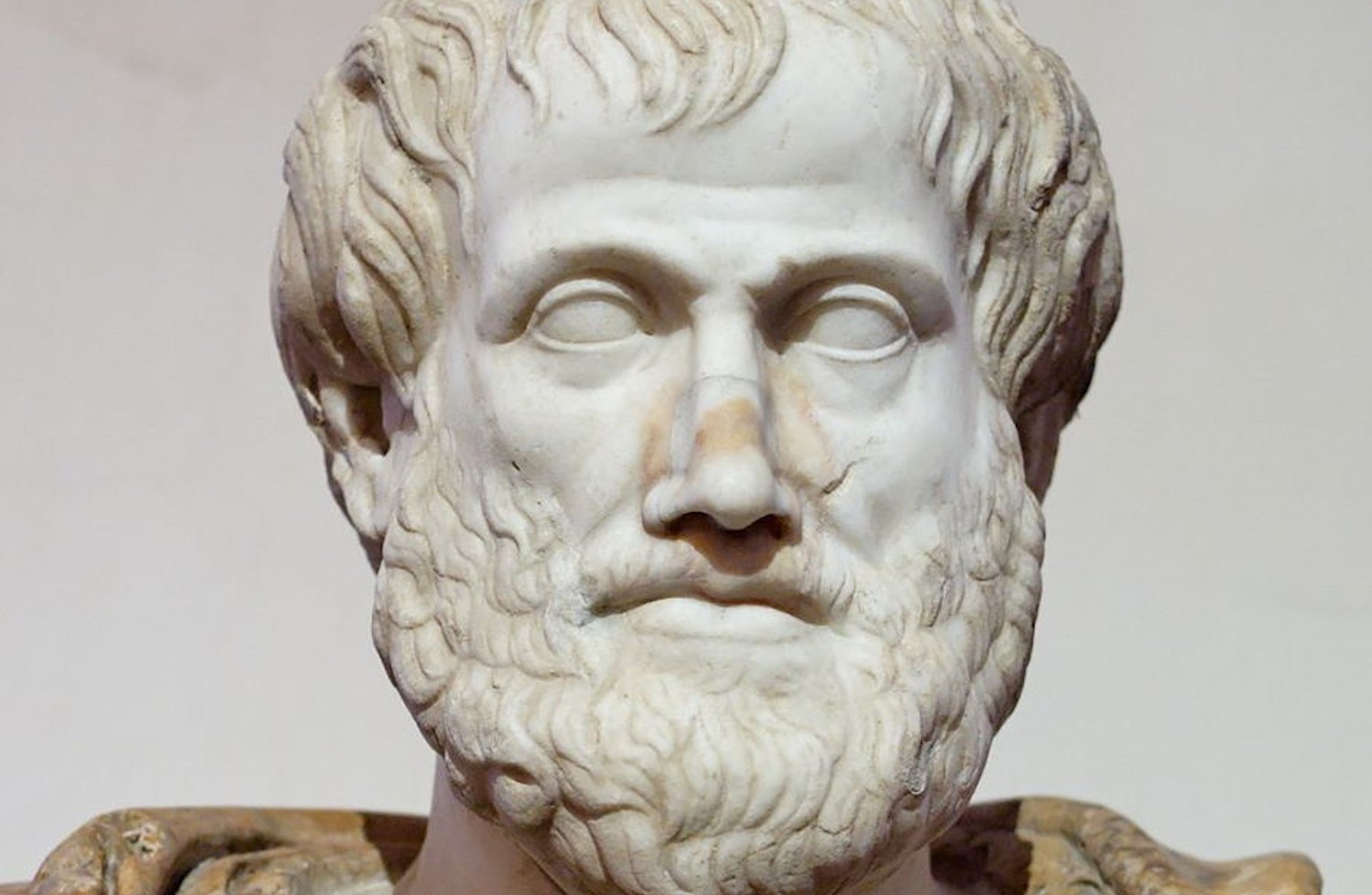

Image of Aristotle – wikimedia commons – jastrow – pd.

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (1999). ‘Aristotle on knowledge’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/aristotle-on-knowledge/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K. Smith 1999