The potential of role-model education. In this article, Daniel Rose examines the role and potential of the educator as a role model within both formal and informal education.

contents: introduction · the influence of the role model on moral identity · role model education and informal education · role-model education as a basis for mentoring · a critique of role-model education · conclusion · bibliography · how to cite this article

No printed word, nor spoken plea can teach young minds what they should be. Not all the books on all the shelves – but what the teachers are themselves. Rudyard Kipling

What exactly is role-model education? I can think of no clearer way of explaining this most effective of all educational tools than Kipling’s words (above). Children, especially during adolescence – their most vulnerable and impressionable age – are in need of role models, and take them from all areas that are close at hand, whether mass media, parents and family, or their teachers.

Role model education is not concerned with the imparting of knowledge and information, as one might expect from an educational context. Rather, its aim is to expose its target groups to specific attitudes, lifestyles and outlooks, and, in particular, to individuals in which these attitudes and lifestyles are embodied. This educational tool is stressed in informal education settings such as youth movements, where the sometimes charismatic educational youth leader embodies the values that he or she is espousing, and therefore provides a frame of reference for the children. Aliah Schleifer provides us with an example of this from the Muslim home. He asserts that the mother has an incredibly important role to play in the education of her child, simply because she embodies the values that he or she is learning about. He or she now has a chance to experience the ideals that he or she learns about in school. For instance “the child “begins to learn the importance of cleanliness when he sees that she makes wudu before prayer” (Schleifer 1988: 36).

Not only is there no reason for teachers not to utilise these ideas, but rather the teacher has a responsibility to use them, and to be wary of the power behind this concept. Children of this age are incredibly perceptive, and will automatically see through a teacher who tries to convince them of something they are not convinced of themselves. (I have seen this at first hand, in a school with a strong ethos that not all the teachers embody in their personal lives, such as a religious denominational school, where non-practising teachers are forced to lead or facilitate prayer services.)

Role model education can be seen as effective because it bridges the gap between the ideal and reality. Education becomes experiential, as students learn a little about their teachers’ lives, and how they embody the values they are trying to pass on and explore. The gap between theory and practice is bridged, as ideological concepts become realities before the eyes of the students. Once they have truly understood an idea because they have seen it at first hand through teacher’s expression of it in the way they conduct themselves, they are only then in a true position to judge its validity to their life, and then make the relevant lifestyle decision.

The influence of the role model on moral identity

Anton A. Bucher asserts that “Models are one of the most important pedagogical agents in the history of education”. He continues; “Plato mentioned their impact in forming moral consciousness. He warned against bad models, especially gods and heroes in Homer’s epic poems. Young people would imitate their immoral behaviour and adopt their immoral values and attitudes” (Bucher 1997: 620). He goes on to suggest that over the centuries educators have been sensitive to the need for good role models in order to shape desirable moral attitudes in young people, and cites Jesus as the ultimate and most widespread role model from ancient times, through the middle ages, until modern times.

To support his theories of role models and the effect that they had on youth, Bucher collected data from 1150 pupils between the ages of 10 and 18 from Austria and Germany, 53% girls, pupils in each country attending different schools. The data on preferred models was collected in the form of a questionnaire. This included both an open-ended question (What persons are your personal models? Why?), as well as a list of 40 persons (musicians, movie stars, sports figures, intellectuals, politicians, religious persons, as well as persons of social nearness such as parents and siblings). The participants were asked to rate each personality on a scale of 1 (“no model whatever”) to 4 (“a very important model for me”). The results from both types of questions contained in the questionnaire were clear. Those personalities of social nearness to the participants had the greatest “model effect” for them. Mothers, fathers, and relatives were mentioned with the greatest frequency. After that came religious models, and only then mass media personalities such as movie and television stars, and sports figures.

These results were surprising for many people working in pedagogical fields, who had assumed that well-known stars and not parents would be those influencing our youth. In his analysis of these results, Bucher (ibid 625) refers to Mitscherlich who explains that it is “a psychoanalytic commonplace that identification with first referenced persons is more imprinting (also with respect to the moral values and attitudes) than the identification with the heroes of TV and other mass media”. For us, as educators, this enlightens us tremendously as to our capacity to influence our students. Educators can be considered to have near to the same status of social nearness to the children as their own parents. Children, when faced with worthy models at this proximity, will latch on to them and their ideals, and fully consider them as role models.

We can also learn from the mass media models that these children did choose after their models from social nearness. Models included super heroes and film stars that played the role of the “good guy” fighting evil. Bucher (ibid: 624) suggests “these answers demonstrate the distinct manner by which the identity of children and adolescents can be influenced by models, also their moral identity. Several children remembered models who were well suited to their moral universe, characterised by a strong distinction between good and evil.” This surely suggests a thirst within adolescents for a strong positive role model to inspire them in the ways that they know are moral and right. We must conclude that this places the teacher and informal educator in an ideal position to fulfil this role.

This is strongly reflected in the Muslim approach to teachers and their role, as presented in Hasan Langgulung’s essay entitled “Teacher’s Role and Some Aspects of Teaching Methodology: Islamic Approach”. Langgulung suggests that “the position of the teacher as protagonist in the domain of moral values is not limited to direct teacher-pupil interaction in the classroom. The teacher who never marks written exercises or wears indecent type of dress is characterising the notions of duty and responsibility in certain ways. The teacher who openly shows disrespect to some colleagues or the principal is sending across messages unawares about authority and the notions of respect of human beings…we always behave as a good model to the students in conduct and character, because it is part of our obligation and everyone expects us to do so and we have come to expect this of ourselves. It is part of our role of being a teacher.”

Role model education and informal education

In defining informal Jewish education, Barry Chazan identifies eight formal attributes that characterise informal Jewish education. His second attribute is the Centrality of Experience. He says “The notion of experience in education derives from the idea that participating in an event or a moment through the senses and the body enables one to understand a concept, fact or belief in a direct and unmediated way… The focus on experience results in a pedagogy that attempts to create settings which enable values to be experienced personally and events to be experienced in real time and in genuine venues, rather than their being described to the learner. Over the years this notion of experiencing has become closely identified with “experiential education,” often seen as the “calling card” of informal education.”

His eighth attribute of informal Jewish education is the holistic educator. “The informal Jewish educator is a total educational personality who educates by words, deeds, and by shaping a culture of Jewish values and experiences…the informal Jewish educator needs to be an educated and committed Jew. This educator must be knowledgeable since one of the values he/she comes to teach is talmud torah—Jewish knowledge. He/she must be committed to these values since teaching commitment to the Jewish people, to Jewish life, and Jewish values is at the heart of the enterprise. Commitment can only be learned if one sees examples of it up close”.

According to Chazan, central to informal education is experience. It is the job of the holistic educator to provide these experiential educational experiences, and one of the ways that s/he does this is through the educators very essence, personality and lifestyle, which is all on offer to the participant to interact with and be inspired by. At the core of informal education is role-model education, and the most natural educational context that provides the ideal forum for role-model education is of course informal education. These two educational concepts go hand in hand and go some way to explain the success that informal education achieves in its stated goals. In their discussion of informal education, Jeffs and Smith (1999: 82-5) have also stressed these elements – and the significance of attention to the moral authority of informal educators.

Role-model education as a basis for mentoring

The concept of mentoring as a tool in the development of young people is becoming more and more popular and commonplace. Mentoring is classically defined as a young person is inducted into the world of adulthood with the help of a voluntarily accepted older more experienced guide, who can help ease the young person through that transition via a mixture of support and challenge (Hamilton, 1991; Freedman, 1995). I would argue that fundamental to this process is the younger person learning not just from the experiences of the older person, but also learning and being inspired by the older person his/herself. The intimacy and dynamic caused by the interaction of two persons giving the mutual respect necessary in the context of mentoring, will more often than not lead to the younger person relating not just to the information and experiences transmitted by the older person, but the actual essence of the older person, and this can be a potent ingredient for the development of the younger person.

Interestingly, Kate Philip suggests that there are many different styles of natural mentoring models in operation besides the classic one as defined. These include peer mentoring, unofficial adults, friend to friend and group or team mentoring (Hendry and Philip 1996) (see Philip on mentoring and young people and Jean Rhodes (2001) on mentoring programmes in the US). It is possible to suggest from these observations, that role models are not just those in positions of authority or increased age/experience. Young people can choose their role models from any and every context including their peers. This is clearly seen in peer-led informal educational contexts such as peer-led youth clubs and movements, and can and should impact on our policy when facilitating these institutions.

A critique of role-model education

Although we have seen the efficacy of such an approach to values and moral education, there are problems that may be encountered, both on a practical level for the teachers who have this responsibility as role models, as well as on a theoretical level.

As has been stated, children can be most perceptive, sometimes far more than adults, and will see through the lack of integrity of any educator. This places a tremendous pressure on an educator to live up to the values and ethos of their school, subject, or educational message. If a particular educator does not live up to this, their power as a role model is largely diminished. Rejection of the entire message and package is also risked, if children see even the slightest inconstancies in the role model. This may also have the effect of discouraging prospective educators from entering the profession. Educators must also be vigilant in their personal lives to some extent, to ensure it is not publicly at variance with their educational message. Is this after-hours pressure that few other jobs involve, fair on the educator?

Further to this question, is a more difficult one. Does a school or educational organisation have the right not to employ a teacher because their personal life does not coincide with the ethos of the institution? For example, the tension an institution such as a denominational school experiences when considering the employment of either a teacher from a different faith, or from the same faith but with lesser degree of religious practice in their personal life.

The very practical issue of informality is a problematic one when considering role model education within formal schooling. For a student to link in to the personality and way of life of the teacher, the teacher must to some extent lower some barriers in order to let the child catch a glimpse of what he or she is about. This may lead to obvious dangers such as feelings and emotions towards the teacher and compromise the teacher’s desire for distance to forestall problems of over-familiarity. Role model education thrives on informality – and this is not always possible or appropriate in a classroom context – although with the right balance, can and will be effective even with this formal teacher-student relationship. However, as mentioned earlier, this is one of the very strengths of informal education, with role-model education central to its efficacy.

It can be challenged that role model education will stand in the way of true impartiality. It is arguably the goal of every teacher or educator to explore an impartial curriculum, presenting divergent opinions, providing students with the skills to make decisions for themselves, even if within the boundaries of specific ideologies and belief systems. This is especially the case for concepts as subjective as values and morals, which often find themselves the focus of informal education. The participants may have difficulty forming their own opinions and acknowledging the impartiality of the curriculum if the teacher has become a strong role model for them. The educators own lifestyle and value system may become front runner in competing for the attention of the students. (This of course becomes less of a problem for denominational schools, where the lifestyle and outlook of the teacher is the same as that of the ethos and message of the school. However, this can also be seen as an oversimplification, for there can be many different approaches and outlooks within one denomination.)

On a grand and theoretical plain, Bucher (1997: 620) worries about role models and the power of influence that they wield, and potential for evil misuse as seen by totalitarian systems such as National Socialism. He also refers to thinkers who fear there is a “lack of compatibility between models and education on behalf of children’s self-realisation. They believe that models would prevent the development of an autonomous moral identity.”

Conclusion

All educators, whether formal or informal, bear the burden of role-model education equally. However, to see it as a burden, misses the powerful potential and exciting educational opportunities that it can provide. Role-model education allows those values and ideas that are central to our curriculum to become an experiential educational experience, merely through “hanging out with the educator”. This is arguably the essence of informal education, and in fact all effective education.

This paper therefore recommends added exposure to the educator in all educational contexts. Informal education will do this more naturally than formal, but there is no reason to suggest that it is inappropriate in either context. Let us try to facilitate natural “encounters” between students and educators, both within and without of the educational context.

We discussed briefly the concept of mentoring. Let me suggest some further examples of allowing the role-model to be a powerful educational tool through these “encounters”. This will take place in any opportunity where the educator can play a more natural informal role, such as weekend retreats, educational trips and visits, extra-curricular programmes such as sports and recreational events.

Obviously, informal education lends itself better and more naturally to this mode of education, and it is harder to think of contexts from the school where it can be equally utilised. However, a perfect forum for the increased informality necessary for role-model education within the formality of the teacher/student relationship would be on an educational visit/school trip.

On a school trip, whether a one-day trip to a museum, or a month in a foreign country, everything about the student/teacher relationship has the potential to become less formal, while still being professional and controlled. From hiking to kayaking, walking through ancient archaeological remains to travelling for hours on buses, interaction is far easier and more natural. Conversations involve all sorts of topics, and students are afforded the opportunity to gain an inkling as to whom the teacher actually is, rather than merely what he or she tries to convey. This allows them to see that the values espoused in the classroom do not stay in the classroom, but are inherent in the life and lifestyle of the teacher.

It is just these types of encounters that we should be providing for our charges in order to maximise ourselves and our colleagues as role-models to these youth, in order to develop them as people and further our educational goals.

Bibliography

A. A. Bucher (1997) ‘The Influence of Models in Forming Moral Identity’, International Journal of Educational Research Vol. 27 No. 7.

P. Burnard (1991) Experiential Learning in Action, Avebury, Aldershot.

B. Chazan (2002) ‘The Philosophy of Informal Jewish Education’ (Commissioned article for the Jewish Agency for Israel, December 2002) available in the informal education archives.

C. Criticos (ed.) (1989) Experiential Learning in Formal and Non-Formal Education, Media Resource Centre, Department of Education, University of Durban.

M. Freedman (1993) The Kindness of Strangers : adult mentors, urban youth and the new voluntanism, San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

S. F. Hamilton (1991) Unrelated Adults in Adolescent Lives, New York: Cornell University

J. Hammond et al. (1990) New Methods in RE: An Experiential Approach, London: Oliver and Boyd.

P. Harling (1984) New Directions in Educational Leadership, The Falmer Press.

J. Hull (1982) New Directions in Religious Education, The Falmer Press.

T. Jeffs and M. K. Smith (1999) Informal Education. Conversation, democracy and learning, Ticknall: Education Now Books.

D. Kolb (1984) Experiential Learning, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

H. Langgulung (1983) ‘Teacher’s Role and Some Aspects of Teaching Methodology: Islamic Approach’,Muslim Educational Quarterly (Vol. 1 No. 1.

A. Mitscherlich (1963) Auf dem Weg zur vaterlosen Gesselschaft. Ideen zur Sozialpsychologie. Munchen:Piper

National Curriculum Council (1993) Spiritual and Moral Development – A Discussion Paper, London: N.C.C.

OFSTED (1994) Spiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural Development, London: OFSTED.

Philip, K. and Hendry, L. B. (1996) ‘Young People and Mentoring: Towards a Typology?’ Journal of Adolescence, 19:189-201.

Rhodes, J. (2001) ‘Youth Mentoring in Perspective’, The Center Summer. Republished in the encylopedia of informal education, www.infed.org/learningmentors/youth_mentoring_in_perspective.htm.

SCAA (1995) Spiritual and Moral Development (SCAA Discussion Papers No. 3), London: SCAA.

SCAA (1996) Education for Adult Life: The Spiritual and Moral Development of Young People (SCAA Discussion Papers No. 6), London: SCAA.

SCAA (1996) A Guide to the National Curriculum (School Curriculum and Assessment Authority) , London: SCAA.

SCAA (1996) Religious Education, Model Syllabuses; Model One – Living Faiths Today, London: School Curriculum and Assessment Authority

SCAA (1996) Religious Education, Model Syllabuses; Model One – Questions and Teachings, London: School Curriculum and Assessment Authority.

A. Schleifer (1988) ‘The Role of the Muslim Mother in Education in Contemporary Society’, Muslim Educational Quarterly Vol. 5 No.2.

R. J. Starratt (1993) The Drama of Leadership, The Falmer Press.

H. Thelen (1954) The Dynamics of Groups at Work, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

S. Warner Weil and I. McGill (ed.) (1989) Making Sense of Experiential Learning, Buckingham: Open University Press.

Education Reform Act 1988, London: HMSO.

Education (Schools) Act 1992, London: HMSO

Daniel Rose was born and bred in London and moved to Israel in September 1999. With a background in formal (High School Jewish Studies Teacher in London area) and informal Jewish education (youth movements and synagogue organisations in U.K. and Israel), he presently lectures 18-19 year olds’ from Britain, America, and Israel, on a gap year programme in Israel, teaching classical Jewish texts, modern Jewish history, and Informal Jewish education and youth leadership. His undergraduate degree is from Jews’ College, London University, in Jewish Studies and has a PGCE and Masters in Religious Education from the Institute of Education, London University. He has just begun a doctorate in Jewish education at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

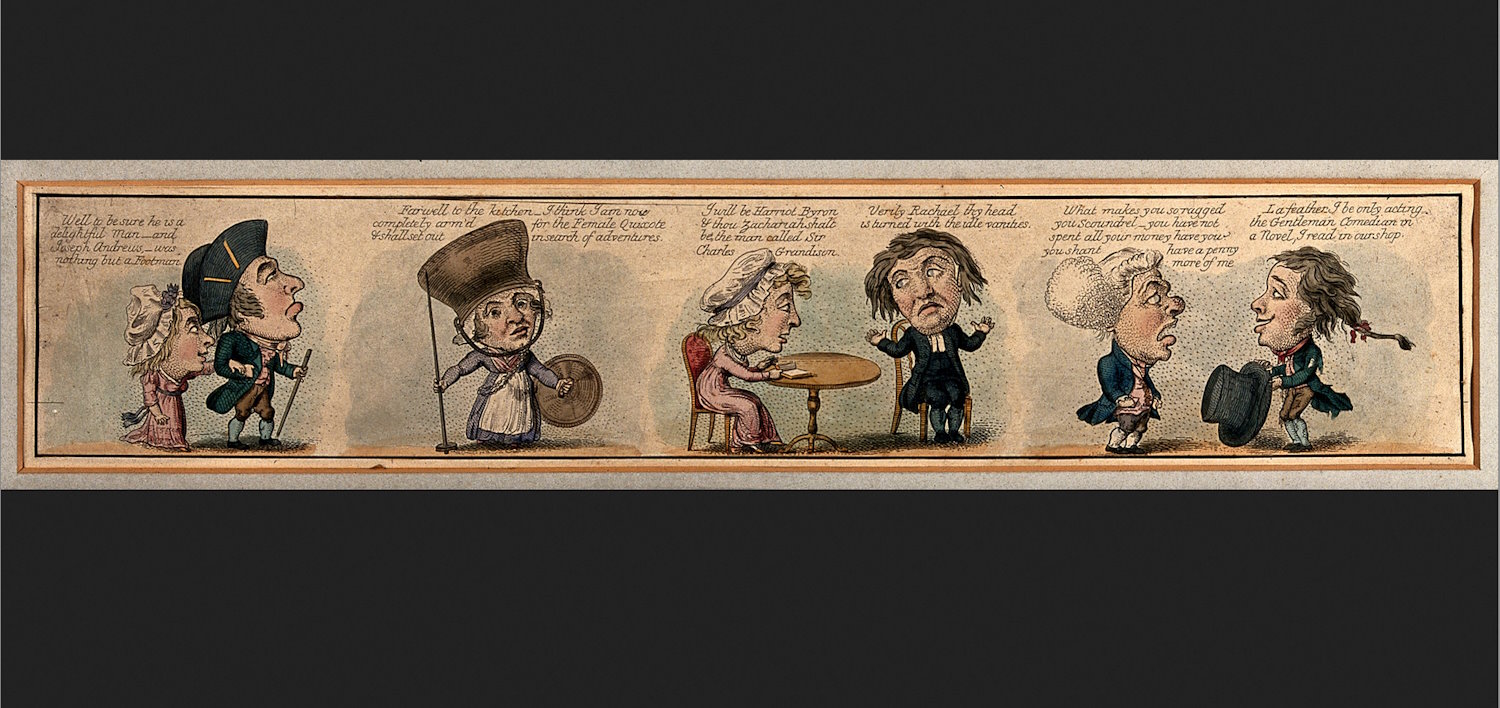

Acknowledgement: People living a life of fantasy as a result of being excessively influenced by reading novels. Coloured etching after G.M. Woodward, 1800. Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection.

How to cite this article: Rose, D. (2004). ‘The potential of role-model education, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/the-potential-of-role-model-education/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Daniel Rose 2004