San Francisco Jewish Contemporary Museum reflected in hotel windows across plaza

San Francisco Jewish Contemporary Museum reflected in hotel windows across plaza

sswj | flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In this article Daniel Rose presents the history and background of international Jewish youth movements and the methods and frameworks of informal education they employ.

contents: introduction · informal jewish education · youth movements vs. youth clubs · youth movements and clubs in britain · the classical Jewish youth movement – a historical background · international jewish youth movements in britain and beyond · conclusion · further reading and bibliography · links · how to cite this article

In his article “The Philosophy of Jewish informal education” Barry Chazan gives several examples of where informal Jewish education happens. These include Jewish community centres, adult learning programmes, Jewish family learning programmes, Jewish travel, Jewish camps and retreats, and Jewish youth movements and organizations. I would argue that classical Jewish youth movements were the pioneers of informal Jewish education leading to the spread of this phenomenon to many different frameworks, including formal education settings. Today, many of Chazan’s examples of informal Jewish education are offered by youth movements which provide for their participants a wide social and educational framework for their teenage years. In this article, the background and history to the development of these youth movements will be presented, and their methods of informal Jewish education examined. First, let us examine what exactly informal Jewish education is, and how it may differ from general informal education.

Informal Jewish education

In the same article, Chazan suggests that Jewish and general informal education share six of the eight defining characteristics that he delineates in defining informal Jewish education. These shared characteristics are: both are person-centered, experience-oriented, and interactive, and both promote a learning and experiencing community, a culture of education, and content that engages. However, he also suggests that informal Jewish education can be considered a unique category of its own, differing from general informal education in two major respects: its curriculum of experiences and values and its holistic educator.

Chazan suggests that informal Jewish education is inherently about affecting the lifestyle and identity of Jews. General informal education is often about learning a skill or improving one’s skills, especially life skills, but rarely about ultimate identity or character education. Because of this, these two models of informal education also have divergent conceptions of the role of the educator. Informal Jewish educators are inherently shapers of Jewish experience and role models of Jewish lifestyle, as opposed to the good general informal educator who is focused on helping to develop skills and not on shaping identity or group loyalties.

Chazan succinctly defines informal Jewish education as:

Informal Jewish education is aimed at the personal growth of Jews of all ages. It happens through the individual’s actively experiencing a diversity of Jewish moments and values that are regarded as worthwhile. It works by creating venues, by developing a total educational culture, and by co-opting the social context. It is based on a curriculum of Jewish values and experiences that is presented in a dynamic and flexible manner. As an activity, it does not call for any one venue but may happen in a variety of settings. It evokes pleasurable feelings and memories. It requires Jewishly literate educators with a “teaching” style that is highly interactive and participatory, who are willing to make maximal use of self and personal lifestyle in their educational work.

Youth movements vs. youth clubs

In this article, we are going to concentrate on the earliest, and some would argue most potent framework for Jewish informal education – the youth movement. Let us make sure that we understand what a youth movement is, and how it differs from any other youth organization or club.

Broken down to its most simple elements, a youth movement is an organization that has a strong ideology, and focuses its activities and educational content towards that ideology. Every decision made in the movement, from programming to recruitment policies, publications to catering plans, first and foremost must centre on the ideology of the movement. In contrast to this, a club or organization has the participant at its centre, and their needs are first and foremost, even though there may also be an underlying, implicit agenda that runs the club, such as the development of good citizenship, or providing a Jewish social context for its participants.

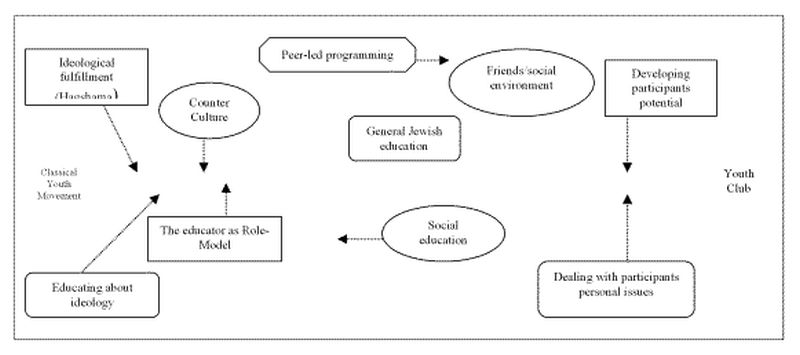

In truth, most Jewish organizations that utilize informal education cannot be easily categorized as one or the other, the reality of these organizations being far more complex. Each movement/organization has its particular agenda and mix of issues and policies that define where on the spectrum of movement versus club it sits. In Figure 1, a list of 10 issues can be found, each aligning itself on that spectrum, with classical youth movements focusing on the issues to the left extreme, and clubs and general Jewish organizations on the right extreme. Very few movements can be said to be found only on the left extreme, only concerned with those issues, and the same can be said for clubs on the left. In reality, most movements/organizations, are a complex mix somewhere between the two extremes.

Figure 1: Central issues contrasting classical Jewish youth movements from Jewish clubs and organizations

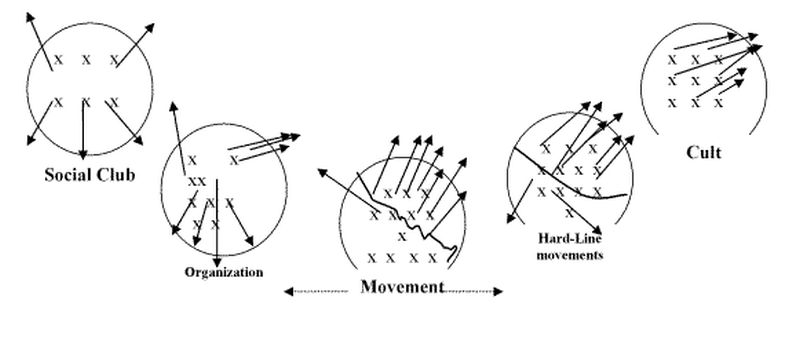

Figure 2 describes various organizations and their members, and where their personal ideologies vis-a-vis the movements’/organizations’ ideologies are. Each x represents a member, with the arrow leading from the x, their personal ideology. This suggests that a true movement verges on a cult, and all the negative connotations that go with that. Conversely, an organization where each member tries to lead the organization on their own path, lacks dynamic leadership, growth, and “movement”. This model, called the pendulum model, suggests that each organization oscillates between these positions, rarely finding themselves at the extremes. Classical Jewish youth movements would find themselves generally towards the right side of the pendulum swing, and it is these movements that I wish to focus on for the remainder of this paper.

Figure 2: The pendulum model of youth organizations

Youth movements and clubs in Britain

The first Jewish youth club established in Britain was the German Street Girls Club in London’s East End in 1883, and had as its aspiration the integration of young, newly immigrated, Eastern European Jews into mainstream British society. The German Street Girls Club was the first of many youth clubs established during that period of high immigration by Ashkenazi Jews (Jews of European origin) to the East End until after the Second World War. The goals of these first Jewish youth organisations was to transform barely literate young Polish and Russian Jews into fully integrated proud members of the Anglo-Jewish community in particular, and English society as a whole. This expressed aim was not of assimilation per se, but rather of integration, focusing on the values of the English upper middle classes.

Today, there are tens of Jewish youth clubs found in each Jewish community in Britain, many of them based in Synagogue and communal organisations, and some are nationwide, such as Jewish Scouts and Guides, Maccabi Union sports clubs, and the Association of Jewish Sixth Formers. Another example of these is the Jewish Lads’ and Girls’ Brigade, another uniformed youth organization and one the earliest Jewish youth organisations in Britain. Established in 1895 by Colonel Albert Goldsmid, a senior army officer, for children of the many poor Jewish immigrant families who were coming into Britain at that time. The first company was launched in London’s East End but others soon appeared throughout the city and the provinces. In the early days the Brigade catered for boys only, providing them with more than just spare-time activities. It offered food, clothes and the chance to learn skills which might help in finding a job. Then, as now, camps were an important part of Brigade life. Just 19 boys attended the first summer camp in 1896. Today, several hundred youngsters camp with JLGB throughout the year. In the mould of youth clubs rather than movements, JLGB has no expressed ideology, other than providing a fun. weekly program of activities and an exciting program of weekend, summer and winter camps, giving members a chance to participate in an enormous range of sports, activities and hobbies, as well as leadership training and service to the community.

These early Anglo-Jewish youth organisations were clearly social more than ideological in their nature, and the forerunners of today’s Jewish youth clubs and organisations. However, just a few years later those youth clubs were joined by the first classical Zionist youth movements in Britain, with the Federation of Zionist Youth the first to appear in 1910, a specifically British movement. However, most classical Zionist youth movements appeared in the thirties and forties, after they had first been established in Europe. These movements were ideological in their orientation, often having strong links to a political parent movement in Palestine. These youth movements were clearly distinct from the Jewish youth club whose roots were in Jewish acculturation and the Anglo-Jewish establishment. Almost all of these movements are international being found in Palestine and later Israel, as well as all over the Jewish world. They have concerns and policies that transcend Anglo-Jewry, and educate towards values and ideals which if not directly oppose normative society, at the very least, present an alternative vision of society, which is expressed through the sub-culture of the movement. Today there are in the region of fifteen Jewish youth movements in the United Kingdom with a membership of thousands of Jewish youth.

The classical Jewish youth movement – a historical background

Zionist youth movements play a tremendously important role in Jewish communities across the Jewish world, including Europe, North America, South America, Australia, and in Israel. They are a dynamic and powerful source of Jewish identity and knowledge for hundreds of thousands of young Jews around the world, using their passion and commitment to their ideology and charismatic leaders to literally transform peoples lives. Most were established in Eastern Europe towards the beginning of the twentieth century, motivated by the desire for the national revival of the Jewish people in their homeland, forming the youth wings to many Zionist organizations bringing Zionism to the agenda of the Jewish and larger world. Many of them, like other European youth movements, they were critical of established society and idealized a return to nature and a simpler – rural – way of life.

The first Zionist youth movement was Blau-Weiss (Blue-White), established in Germany before World War I (1912). The Jewish youth movement with the largest membership and most significant impact at the time, though, was Hashomer Hatza’ir (founded in Poland in 1913), with its socialist-Zionist ideology.

Youth movements played an important role in the history of Jewry between the two world wars. Their influence greatly exceeded their numerical importance in community organization, education, political awareness and Zionist consciousness. One of the major ways to achieve fulfilment of their ideology (Hagshama) was to immigrate to Palestine as it was then (termed Aliya – literally to “go up”). As graduates of these European youth movements reached Palestine, they began to make a profound impact to the community there. Practically speaking, they were the builders of the kibbutz movement.

The power of these young ideologues and their ideals became apparent, tragically, during the Holocaust. They remained active throughout this time of destruction, and their leaders orchestrated Jewish organization and resistance in ghettoes and camps. They also helped plan and implement the Bericha (escape from Europe) movement after the Holocaust. Most of the surviving members eventually settled in Palestine. The destruction of the Jewish communities of central and Eastern Europe marked the end of the Jewish youth movements there (although they are still active in Western Europe to this day).

Most of the youth movements that originated in Eastern Europe established worldwide organizations but these had much less impact there, especially in the United States where young people tend to join social organizations that are less political. American Jewish teenagers, thus, mostly belong not to Zionist youth movements but to organizations such as B’nai B’rith, associations of synagogues, or local and countrywide community organizations which also try to impart Jewish-Zionist consciousness, and have later become more focused on Zionism, as the establishment of the State of Israel caused Zionism to become more central to Jewish identity. The European branches of these movements proved more successful and important than their American counter-parts, especially as Jewish life proved more precarious than in North America.

Youth movements in Palestine began to organize in the 1920s, chiefly under the influence of movement alumni who had come from the Diaspora. They stressed togetherness, pioneering and personal fulfilment, especially on the kibbutz. There, as in Europe, their public impact and influence on young people was immense. Most of the movements were affiliated with political entities or even established them. Only the Scouts movement defined itself as non-partisan politically, while also maintained a Zionist ideology, educating its members in a national pioneering spirit and establishing agricultural training groups that founded their own kibbutzim.

Today, Zionist youth movements remain a powerful force in Diaspora Jewish communities around the world, as well as in Israel and on Israeli society. In the Diaspora especially, they play a large part in raising Jewish consciousness among youth. Activities focus on Jewish subjects and encourage members to congregate at Jewish institutions such as synagogues; thus strengthening ties with other young Jews. Most youth movements encourage their members to spend time in Israel and have programs in Israel. Although all Zionist movements have Zionism and Aliya at their core, not all of the participants relate to this or are willing to fulfil these ideals. In fact, some parents in fact feel a little threatened by the focus on Zionism and aliya. However, most realize the benefits involvement in the movement brings, such as increased Jewish identity, knowledge and practice, as well as a social framework, which often they feel far outweigh the risks of their children being led towards the fulfilment of this nationalist agenda.

International Jewish youth movements in Britain and beyond

There are 15 Zionist youth movements active in Britain, most of which have branches in many different countries. There are a handful of movements that are specific to one country, such as in Britain, the USA, Australia, and in Israel. Here is a brief overview of some of the major movements, their history and ideologies, beginning with international movements that are found in the United Kingdom.

BETAR (the initials of Brit Yosef Trumpeldor, Joseph Trumpeldor Alliance), the educational youth movement of the Revisionist Zionist Organization and, subsequently, the Herut movement (and later Likud political party).

Established: December 1923 in Riga, Latvia.

Ideology: Included the establishment of a Jewish state in all of the territory of Mandatory Palestine, ingathering of the exiles, Zionism without a socialist component, a just society, military training for self-defense and a pioneering spirit.

Today: It is active today in Israel and in the Diaspora, with a membership of 14,500 in Israel and 8,500 around the world.

BNEI AKIVA is the largest religious Zionist youth movement, and has political ties in Israel to the National Religious Party. World parent body is the Mizrachi movement.

Established: Jerusalem in 1929 (Forerunners existed in Poland and Eastern Europe under the names of Hashomer Hadati and Brit Hanoar even earlier than this).World Organization was founded in 1954.

Ideology: A philosophy of Torah Ve’avoda (literally Torah and working the land) – a fusion of Orthodox observance of religious commandments and Zionist pioneering on the land.

Today: The movement has some 70,000 members in Israel as well as 45,000 in Diaspora communities around the world.

Britain: Formed in London as early as 1939 under the name of Bachad, and then as Bnei Akiva in 1942), and quickly spread throughout the country, including Scotland and Ireland. Today, Bnei Akiva is the largest British Jewish youth movement, with 1000 official members, 700-800 participants of summer and winter camps, and as many as 3000 casual and frequent participants throughout the year

HABONIM-DROR is the amalgamation of two movements – Habonim and Dror. The parent movement is the United Kibbutz Movement and is associated with the Zionist Labour Movement.

Established: Dror was established in 1915 in Russia, and Habonim in London in 1929. The two movements joined together in 1980 when their parent kibbutz movements did the same.

Ideology: Habonim’s original ideology was to foster Jewish culture, the Hebrew language, and pioneering in Palestine. Dror’s ideology was based on traditional socialist-Zionism. Today, the united movement shares both of these ideologies.

Today: One of the largest international Jewish youth movements, in 22 countries with over 10,000 members.

Britain: Dror was established in the UK in 1961. Habonim was first founded in London in 1929, originally as a response to Anglo-Jewish youth organizations that were focused on integration rather than national Judaism and its revival. They amalgamated at the same time as the world movements, in 1980.

HANOAR HATZIONI, is a pioneering Zionist scouting youth movement, supporting different types of settlement – kibbutz, moshav and development towns.

Established: Founded in Poland in 1932.

Ideology: Strives to inculcate its members with a pioneering, pluralistic outlook. Main focuses are Zionism, Israel, Judaism and Tzofiut (scouting).

Today: Hanoar Hatzioni currently has over 10,000 members in 39 communities worldwide

Britain: Established in the UK in 1956, offering an alternative to the highly political Zionist movements, and the non-political assimilationist youth clubs.

The following movements exist only in the UK.

FZY, the Federation of Zionist Youth, is one of the largest youth movements in Britain, taking by far the largest number of participants to Israel at ages 16 for summer tour, and 18 for Year Course. FZY is twinned with Young Judaea in USA and the Tzofim (scouts) in Israel.

Established: Formed in 1910, although the name FZY was first used in 1935.

Ideology: FZY’s ideology has four specific aims – tarbut (celebration and development of Jewish culture); tzedaka (charity and the values of righteousness); magen (literally shield, the defense of Jewish rights) and aliya (the belief that all Jews should live in Israel). These four pillars are achieved through the medium of pluralism within Judaism and Zionism.

Today: FZY leads the way for British movements, regularly bringing 350 members to Israel for 4 weeks at age 16, and more than 50 members each year spend a year in Israel with FZY at 18.

RSY-NETZER is the largest youth movement from the Reform Jewish community in Britain. RSY stands for Reform Synagogue Youth and Netzer stands for Noar Tzioni Reformi (Reform Zionist youth). The movement’s parent body is the Reform Synagogues of Great Britain, and is affiliated to the worldwide Reform Zionist youth movement Netzer Olami.

Established: RSY-Netzer was formed in 1982, after an ideological decision that moved the movement from a Reform Jewish youth organization to an ideological Reform Zionist youth movement.

Ideology: Reform Judaism and Zionism, with a central focus on Tikkun Olam (repair of the world).

The following movements exist only in the USA.

YOUNG JUDAEA is the largest Zionist youth movement in the USA, with thousands of participants attending camps and tours of Israel every year, as well as the largest single year-program in Israel for foreign students, with 3-400 participants each year.

Established: Founded in 1909, Young Judaea is the oldest Zionist youth movement in the United States. In 1936 Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization in America became Young Judaea’s parent body, providing them with vital financial support.

Ideology: Three central areas: Judaism – the striving to impart a sense of value and love for Jewish tradition and rituals within a religiously pluralistic environment. Jewish Identity – strengthening Jewish identity and pride by educating about Jewish heritage, history and current affairs. Zionism – the belief that Israel is central to all of Jewish life, Young Judaea’s primary goal is the furthering of the national aspirations of the Jewish people, with Jewish and Zionist education and the promotion of aliyah being integral steps in that process.

Today: Young Judaea has 7000 members, running events and activities in 16 regions throughout the United States.

USY (United Synagogue Youth) is the youth movement associated with the Conservative Movement in America, and is affiliated to the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism.

Established: In 1951 in New York, USY was first founded, catering for 13-17 year olds, and involved originally 500 participants from 65 different communities across 14 different states, as well as Canada.

Ideology: To develop and strengthen Jewish identity, attachment to the Jewish people and the Land of Israel, loyalty to the synagogue and Jewish ritual (Conservative), and to encourage engagement with Jewish study.

Today: USY runs high school programs, pilgrim trips around the world, including Israel and Europe, trips around the USA, as well as year programs in Israel. USY functions and has chapters in 64 states and regions in the USA and Canada.

The informal Jewish education of the youth movement

Jewish youth movements have repeatedly been referred to in this article as the paradigm provider of informal Jewish education. This is not only because they are historically the first to use these educational methods, but also because of the way they employ this mode of Jewish education in delivering their curriculum (their ideology) to their members. At the centre of their methods is the focus on experiential education (see Kolb and Chazan). They attempt, with tremendous success, in providing experiential educational contexts for their participants to relate to, and internalize.

Although Chazan separates youth movements, camp, weekend retreats and educational trips abroad into separate categories. Today these are all provided first and foremost (although not exclusively) by youth movements. These movements, largely run by young graduates in their early twenties (movements generally have very few professional permanent staffing, and are normally run on a volunteer basis), provide young Jewish people with fantastic social and educational opportunities. From month-long summer tours of Israel, two week residential camps around the country, residential weekends in different communities, to weekly meetings where catching up with friends and the educational/ideological issues that are on the agenda are all provided by these movements around the world. Each event and program is designed to maximize fun and social opportunities, as well as the provision of education in an experiential context and mode.

Conclusion

Jewish communities around the world find themselves waging a war against Jewish assimilation and the drifting away from Judaism and Jewish identity of their youth. More and more they are realizing that youth movements and informal Jewish education is an important way to achieve their goals, providing Jewish youth with a strong sense of affiliation to the Jewish community and world, and that these movements should be celebrated and fully supported in every way.

Further reading and bibliography

Sidney Bunt (1975) Jewish Youth Work. Past, present and future, London: Bedford Square Press. 240 pages. Provides a good introduction to Jewish youth work. While there is substantial material examining the then current state of the work, the bulk of the book is devoted to tracing the emergence and development of the work.

Barry Chazan (2003), ‘The philosophy of informal Jewish education’ The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, www.infed.org/informaleducation/informal_jewish_education.htm . A now classic paper exploring informal Jewish education.

Kadish, S. (1995) ‘A Good Jew and a Good Englishman’. The Jewish Lads’ and Girls’ Brigade 1895 – 1995, London, Vallentine Mitchell.

Rose, C. (1998) A Youth Club for Its Time. A personal history of the Clapton Jewish Youth Centre 1946 – 1976, Leicester: Youth Work Press. Originally marketed as a ‘delightful and nostalgic account of life at the club ‘- this book is something rather more. Celia Rose has gone back to old members and asked them to reflect on their experience. As such it provides some useful insights into the long term impact of Jewish youth work.

Sorin,, G. (1990) The Nurturing Neighbourhood. Jewish community and the Brownsville Boys Club 1940-1990, New York, New York University Press.

Links

Daniel Rose was born and bred in London and moved to Israel in September 1999. With a background in formal (High School Jewish Studies Teacher in London area) and informal Jewish education (youth movements and synagogue organisations in U.K. and Israel), he presently lectures 18-19 year olds’ from Britain, America, and Israel, on a gap year programme in Israel, teaching classical Jewish texts, modern Jewish history, and Informal Jewish education and youth leadership. His undergraduate degree is from Jews’ College, London University, in Jewish Studies and has a PGCE and Masters in Religious Education from the Institute of Education, London University. He has just begun a doctorate in Jewish education at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

How to cite this article: Rose D. (2005). ‘The world of the Jewish youth movement’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/the-world-of-the-jewish-youth-movement/. Retrieved: insert date]

© Daniel Rose 2005