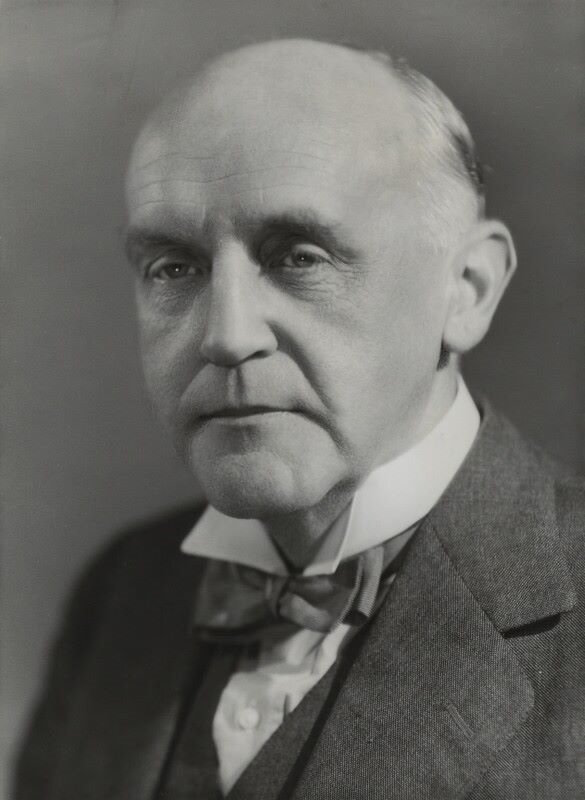

Alexander Paterson, youth work and prison reform. Alexander Paterson (1884-1947) had a profound influence on social policy in Britain. Now remembered as a prison reformer, he was also a key figure in the establishment of TOC H and an influential figure in boys’ club work. Paterson’s book Across the Bridges (1911) was also an important exploration of poverty and social conditions of Bermondsey and the dockland districts of South London. Here we explore his contribution.

contents: introduction · alexander paterson and the oxford and bermondsey club · across the bridges · toc h · alexander paterson and prison reform · conclusion · further reading and bibliography · links · how to cite this article

Picture: A Bermondsey rest centre 1941 (Second World War) by Mabel Hutchinson pd | Wikimedia Commons

________

‘Sir Alexander (Alec) Henry Paterson (1884-1947) was born on November 20, 1884 in Bowden, Cheshire, attended Bowden College and went up to the University of Oxford in 1902. From an early age, he appeared to be set for a ‘career’ in (Liberal) politics. Clement Atlee recalls him coming up to his college (University College) in his second year. He has commented, ‘Although younger than most of those of his year he very soon became an outstanding influence in the life of the college… [H]is greatness consisted essentially in the power of his personality’ (writing in Ruck 1951: 7). At Oxford Paterson took honours in Greats and became an officer of the Union (the other officers included William Temple and Herbert du Parcq) (Ruck 1951: 12).

In his freshman year at Oxford Paterson encountered Dr John Stansfeld who had pioneered the Oxford Medical Mission (later known as the Oxford and Bermondsey Club) and a range of boys’ work in Bermondsey. He invited Paterson to visit and to give the Mission a fortnight’s trial – and Paterson was moved by what he saw. As Ronald Selby Wright (1951: 28) put it, Alexander Paterson became the leader of ‘a very small but quite remarkable group’ at university.

It was a group of men whose true greatness was partly to be found in their almost deliberate obscurity; only the inner circle know how much they have given to the world at large. Barclay Baron, George Troup, Donald Hankey, Roland Phillips, for example with Alec Paterson himself as the king of them all, are known and loved in the wide yet reserved world of Boys’ Clubs, and Toe H. and Social Reform. Yet even among those who most benefited by them, so often their names are but names: and that I submit surely is part of their greatness. Not one of them sought fame, but all of them earned it; none sought riches, but how great are the riches they have bestowed on the world! They did not talk about fellowship and service : they served their fellows without hope or desire of reward—except the only reward really worth having—that of knowing that they did God’s will. They served their fellows without fear of the consequences. (op. cit.)

Alexander (Alec) Patterson was to live in Bermondsey for 21 years – and was in touch with the work there throughout his life. On leaving Oxford he took up a minor Civil Service post. Initially, he lived at the Mission – but he soon moved out into a two-roomed tenement close by ‘in the worst building he could find and in the roughest riverside street’. There he fought ‘an unequal battle with vermin’ and became ‘will-nilly, the adviser of his teaming neighbours and the godfather of many of their children’ (Baron 1952: 163). He also gave up his post in the Civil Service and became a supernumerary, unpaid, teacher in a local elementary school (using his savings and a gift from his mother). He was later to write about the experiences of local people in moving terms in Across the Bridges (1911) and to call upon the better-off to take action.

Not surprisingly given the connections of many of the residents of the Oxford and Bermondsey club, Alexander Paterson’s growing expertise around and knowledge of the lives and children and young men became known to Herbert Samuel who was drafting the Children Bill (which became the Children Act 1908). As a result, Paterson wrote more than twenty amendments to the draft – all of which appeared in the final Act.

Alec Paterson’s concern with the prison system also dated from around this time. One of the club members ‘Jimmy’ (who lived in considerable poverty) killed his young wife (in 1906) (later described by Paterson in Ruck 1951: 32). Paterson understood the circumstances and viewed ‘Jimmy’ as a friend. He fought on his behalf throughout his trial, stood by him during his long imprisonment and looked after his baby. He also paid for Jimmy and his child to emigrate on his release. Baron comments ‘It was this love for men, this capacity for walking beside them, linked with a bold imagination and a stubborn will, which he now dedicated to the reform of the criminal system and of the penal system’ (1952: 165). In 1909 Winston Churchill, then Home Secretary, recruited Paterson and to discuss with discharged convicts their futures. It was the first experiment in after-care for convicts. He also became Assistant Director of the Borstal Association (in 1908).

During this time he remained deeply involved in the work of the Oxford and Bermondsey Club. As war approached along with a number of others involved in the club he joined the local territorials (22nd Battalion of the Queen’s) and was soon in action. He was twice recommended for a VC, was badly wounded when rescuing a comrade and eventually came home a Captain with a Military Cross. As a result of his injuries, he was in constant pain which, according to Baron (1952: 166) he suffered in silence. Along with some other members of the Oxford and Bermondsey Club (notably Barclay Baron) Alec Paterson was to become involved in the formation of TOC H as a movement.

After the war, he joined the Ministry of Labour for a short while (at first as a Principal Officer) but then, in 1922, was appointed Commissioner of Prisons and Director of Convict Prisons. His appointment didn’t go without comment – there was significant opposition to his progressive ideas. He believed that prisons should focus on rehabilitation rather than punishment. One of his famous statements was that: ‘Men are sent to prison as a punishment, not for punishment’ (quoted by Ruck 1951:13). Alexander Paterson had a major impact on the direction and conduct of Borstals and upon the work of the prison system as a whole.

Alexander Paterson retired as Commissioner in 1946. and was knighted in 1947. However, as Baron comments, he was ‘utterly worked out in body and mind’. He died on died November 7, 1947, a few weeks before the passing of the Criminal Justice Act that bore many of his ideas. Paterson Park, Bermondsey was named after him.

Alexander (Alec) Paterson and the Oxford and Bermondsey Club

Barclay Baron (1952: 162) has commented that John Stansfeld and Alexander Paterson were drawn together at once:

Both headstrong, both prolific in new ideas that could not easily be reconciled, they argued often enough but never came to into any conflict of consequence. For the Doctor respected the powers of the younger man as much as he loved him, and the lieutenant was always loyal to his chief.

When Paterson saw Bermondsey he was ‘conquered’:

He came as a Unitarian, militant in this as in all the principles he held, but a short spell alongside the Doctor changed this deep-founded family tradition: ‘You simply can’t walk the streets of Bermondsey with him’, he said one night to a friend, ‘and not know that Jesus is Divine.’ (Baron 1952: 162)

Barclay Baron (op. cit.) goes on to comment, ‘There was no trace of theological argument about this but a conviction by which a man could, and did, live’.

At the Oxford Medical Mission, boys’ club work was growing quickly. The Mission had taken over an old corset factory (134 Abbey Street) in 1903. Downstairs was a dispensary, upstairs on the first floor a boys’ club. There were also rooms for resident missionaries on the top floor. John Stansfeld’s visits to Oxford Colleges had attracted a remarkable collection of young men to Bermondsey to visit. There is a picture of the officers at a summer camp (at Horndon in 1907) organized by Stansfeld. The group includes Geoffrey Fisher (later Archbishop of Canterbury), Alec Paterson (later Prison Commissioner); Barclay Baron (a key figure in the organization of Toc H) and Stansfeld himself. Other people associated with the work in the first two decades of the twentieth century included William Temple (Archbishop of Canterbury), Clement Attlee (later of the Labour Party and Prime Minister), ‘Tubby’ Clayton (who founded TocH) and Basil Henriques and Waldo Eagar – both later central figures in the boys’ club movement. The Mission was to move out of medical work (with the departure of Stansfeld) and to focus on boys’ and men’s work. First known as the Oxford and Bermondsey Mission, then as the Oxford and Bermondsey Boys’ Club its work and those associated with it had a profound effect on the boys’ club movement (for more on this see the piece on <href=”#club”> Stansfield).

Paterson was never warden of the Oxford and Bermondsey Club but was a constant presence and dominant influence once Stansfeld had left. This wasn’t always a comfortable experience for the wardens as Eagar has noted. W. McG Eagar was a resident before the First World War and took over as Warden after. Alec Paterson questioned Eagar’s efforts to involve the Oxford and Bermondsey Club with the London Federation of Boys’ Clubs and similar other bodies. He also ‘strongly disapproved and held aloof from the subsequent formation of the NABC [National Association of Boys Clubs]’ (Eagar 1953 236n). However, other wardens such as Baron (1952) have spoken in glowing terms of Paterson’s influence. Basil Henriques was also to later talk about his first encounter with Paterson:

It would be foolish of me to try and describe his extraordinary magnetic personality, none of which he has lost in the past twenty-five years. With great vision, with great humour, and with great originality, the man emphasised what I had got from his book [Across the Bridges – see below]. ‘There is a spot of work to be done in Bermondsey; you might as well come and do it’ – no pressure, no undue urging, but the kind of impression: ‘Well, if you haven’t got the decency in you don’t trouble about it’. (Henriques 1937: 20-1)

After Paterson had died, Henriques was to describe him as ‘the greatest inspiration of my life’ (Loewe 1946: 14).

Across the Bridges

Alec (Alexander) Paterson became convinced of the need to communicate something of the poverty, bad housing and waste experienced by local people. He was also keen to share something of the warmth and potential of south London life. His object was to stir an ‘unheeding world’ and ‘shame its conscience for heedlessness of these things hitherto’ (Baron 1952: 163). The result was Across the Bridges (published in 1911). It’s committed, insightful and sympathetic account of local life and experiences (especially concerning children and young people), and his call for personal action hit a chord. Alexander Paterson used stories and observations to make his points and there was little of the rhetoric and moralizing that infected many accounts by other philanthropists. Indeed, Across the Bridges is often witty and humorous. It went through 11 printings – that last of which was in 1928 – and remains a classic of its genre.

The opening pages of the book capture its tone:

It is said by the man who goes down the Strand that across the bridges of the Thames there lies a quarter of London where it is not possible to find a good tailor or a big hotel. Yet in this seeming desert, which stretches for eight miles along the banks of the river, live all but two millions mothers and fathers and children. Their life is full of incident, yet not adventurous. Goodness abounds, but there is little greatness. Few memorable buildings exist on the south bank to attract sightseers from the countryside or colonies. Few streets seem suited for a royal procession. Even the best features have the sombreness of the second-rate. The part that lies closest to the river is far poorer tan the rest. On these streets poverty has set a seal, and its many problems have sunk their tangled roots deep into the life of the people. It is of the hopes and troubles that come to those who live here that these pages will speak. They will be content to trace the life of the average man by the river-side, to show his worth and possibilities, and will fall far short of suggesting the remedies which might transform his character and chances. (Paterson 1911: 1-2).

From there Alexander Paterson goes on to explore local street life, family life, and customs and habits. The central part of the book examines the experiences of childhood with chapters on birth and infancy, education at an elementary school, school influences, and child-life outside school. All these are written with considerable sympathy and based in sharing in the lives of those he writes about. From here he turns to the working lives of boys and young men and how they spend their spare time. There are also chapters of character and religion and youthful offenders. The last part of the book explores marriage, the life of working people and failures. However, Paterson keeps returning to ‘the natural goodness’ of the local people:

In spite of every stupidity and mistake , in spite of the failure and wreckage of weak souls, here, born of the struggle of life, unfold those lives of love and perseverance, that are to the traveller that has eyes to see as the golden furze on the bleakest slope of the mountainside. (Paterson 1911: 262)

The book ends with a call to action on the part of those who have wealth and influence:

The first great struggle is for men to realize that across the bridges there is a great need, which is a reproach to their common sense because it is a great waste of strength and goodness, and to their manliness because it is unutterably sad. Some, moreover, need to learn that there is a bridge, after all, which will bear them to these countless homes of poverty. They will find the way across the river if they come, natural and unassuming, with a pure heart and ready hand, anxious only to serve and learn. They cross, perhaps, in fear and wonder, but find on the other side a happiness which makes [t]hem stay. They meet there gentler spirits with more indomitable courage than their own, and others who are more weak and sinful than they can understand; slowly they begin to share and join hands with all, and in the end rejoice that are as other men. (Paterson 1911: 272-3)

The book has some interesting omissions. First, the area where Paterson lived and upon which he based much of his writing had a large Irish, Catholic population – and it was these who were among the poorest. Indeed, the tenement where he lived was just a few yards from a large Catholic church and convent. Yet no attention is given to this in the book. We can speculate about the reasons for this. Perhaps Alexander Paterson, knowing that many of his readers would harbour significant anti-Catholic prejudices, left this out so as not to colour their reaction to his central message. Perhaps he thought the religious and cultural background of local people was of little significance. This leads on to a second key omission – the failure to discuss in any sustained way the structural and political reasons for the existence of poverty and hardship on the scale he experienced in Bermondsey. It might be that as his was, in significant part, a call for personal action on the part of those with money and influence that attention to the underlying forces helping to structure people’s lives was deemed unnecessary.

Reaction to the book was strong. Eagar comments that was ‘outstandingly popular, and ‘stung the minds and wrung the hearts of dwellers in Mayfair and the comfortable suburbs’ (1952: 382). It became required reading for those at Eton seeking confirmation. Eagar continues:

It conveyed a vast reproach by depicting not only the essential decency but the greater goodness of the river-side poor, whose generosity, unselfishness and uncomplaining cheerfulness made all the more tragic the weary round of casual employment, ill-health and destitution, and the merciless crushing of youthful capacity and hopefulness. (ibid.: 383)

The book certainly drew people into Bermondsey and similar areas ready to contribute and learn. Basil Henriques was a prime example. He describes the book as holding him ‘spellbound’ and as calling him to ‘cross that bridge’ (1937: 20). The Oxford and Bermondsey Mission, then Club, was able to augment its already strong and influential group of residents and supporters. Clement Atlee, also, has talked of staying with Paterson at the Oxford and Bermondsey Mission (while attending an Officer’s school in Bermondsey) and discussing the book (Atlee 1954: 24). Across the Bridges became a key reference point in debates – and stood alongside the best of the outpouring of books about the position of the young in urban areas e.g. Bray’s The Town Child (1907) and Urwick’s Studies of Boy Life in our Cities. It even invited a sequel – London Below Bridges written by Hubert Secretan, then the warden of Oxford and Bermondsey, and published in 1931. Paterson, in his introduction to the book, comments, ‘Transformation has been effected in so short a time. The homes are better, parents are more concerned in the education of their children. The restriction in hours of public houses has given two hours more sleep to every man, woman and child. The schools are based on leadership rather than regulation’. Yet, he continues, ‘There is still waste in South London because human personality is starved in spirit and cramped in growth by the crudeness of its environment and the scarcity of leaders’ (xii-xiii).

TOC H

The TOC H movement grew out of the efforts of Philip Clayton, an army chaplain who had previously been associated with Stansfeld and the Oxford Medical Mission. He had set up a soldier’s rest-house behind Allied lines in Belgium at Gasthuisstraat in autumn 1915. This house – Talbot House (or ‘Toc H’ in signaller’s jargon) – with its chapel in the hop loft at the top of the building, was experienced as a unique place of fellowship and sanctuary. Friendships were formed across ranks – and many discovered a reality in religion for the first time (Rice and Prideaux-Brune 1990). The House remained open until spring 1918 when German advances brought it directly into the battle zone.

Such was the effect of the house, that a number of those who had passed through it wanted to re-create its atmosphere and ethos in peacetime. As Rice and Prideaux-Brune have commented it was two particular aspects that people want to preserve:

Firstly, there was the fellowship of Toc H, something deeper than the much-talked-of ‘comradeship of the trenches’. People found they could create real friendships with those who, in other circumstances, they would never have met. And they realized that such friendships could transform society. One of them wrote afterwars: ‘To conquer hate would be to end the strife of all the ages, but for men to know one another is not difficult, and it is half the battle’.

And then there was the impact of that Upper Room. The chapel was Anglican, but it was not narrowly denominational. The house was Christian, but it offered a welcome to all who entered it. And so those who entered it wanted to preserve a spirit which would overcome the hostility between the different Christian traditions, and would offer a place, within a Christian community, to those who had no clear Christian beliefs. (1990: 10)

It is easy to see why those involved with Oxford and Bermondsey such as Barclay Baron and Alexander Paterson would be part of such efforts. They ran in parallel with their own concerns in Bermondsey. It was not an ex-servicemen organization but an attempt to cultivate and sustain fellowship and an inclusive Christianity for future generations. Indeed Philip ‘Tubby’ Clayton had been a frequent visitor to Oxford and Bermondsey and involved in the work and was later to say that Bermondsey was ‘the true candle of Toc H’ (Baron 1952: 208).

Alec Paterson became the first chairman of Toc H. The earliest statement of the aims of Toc H was drawn up by Tubby Clayton, the Rev ‘Dick’ Sheppard of St Martin-in-the-Fields, and Alexander Patterson early in 1920. The four points of the compass (as they became known) stressed:

1. FRIENDSHIP: To love widely.

2. SERVICE: To build bravely.

3. FAIRMINDEDNESS: To think fairly.

4. THE KINGDOM OF GOD: To witness humbly. (The full statement can be found in Philip ‘Tubby’ Clayton and Toc H).

Toc H was to grow into major movement developing a range of local groups and establishing a number of national houses and holiday homes. It also spread to a number of other countries.

Alexander Paterson and prison reform

After the First World War, there was considerable pressure for change in the prison system. Of particular note was a report by the Prison System Enquiry Committee edited by Stephen Hobhouse and Fenner Brockway (both of whom had been conscientious objectors and imprisoned during the War). As Edwards and Hurley have noted, the publication of the report coincided with the appointment as chairman of the Commission of Maurice Waller; the foundation of the Howard League for Penal Reform by Margery Fry; and the appointment as a Commissioner of Alexander Paterson. They continue:

Paterson was unique amongst Prison Commissioners in having no official connection with the prison service before his appointment…. He is chiefly remembered for his impact on the borstal system but he was also the driving force behind many of the more general reforms of the twenties and thirties.

The impact of new Commissioners was swiftly felt. The convict crop and the broad arrow were abolished, reasonable facilities were made for shaving (until then not even a safety razor had been allowed), the silence rule was greatly relaxed, educational facilities were extended, and provision was made for male prisoners to receive visits from prison visitors. Efforts were made to improve the work available to prisoners, which had fallen off after the end of the war, and a seven-hour working day was introduced in 1923. In 1929, with the help of the Howard League, a pilot scheme for the payment of a small wage to prisoners working in the mat-making shop at Wakefield was established. Public funds were made available for this purpose in 1930 and the scheme was gradually extended. The period of separate confinement was phased out from 1922 and abolished in the Prison Rules 1930. In 1936 all prisoners were allowed to have tobacco, a privilege previously reserved for those serving sentences of four years or more.

The basic idea underpinning Paterson’s approach was that the primary aim of detention was to educate the offender. ‘Deterrence and retribution were achieved by the deprivation of liberty’ (Ruck 1951: 13).

Not surprisingly given his previous experience, Alec Paterson had a special interest in the reform of the borstal system. Established as part of the criminal code in 1908 the Borstal sentence had been built upon a military model of discipline and authority. In contrast, Alexander Paterson looked to the public school system as a template with its ‘conception of building discipline from within, by encouraging the boys’ social instincts of loyalty and esprit de corps, and stimulating their latent capacity for leadership’ (Ruck 1951: 13). He knew the approach worked from his time with the Oxford and Bermondsey Mission.

One of his chief weapons was his influence in making appointments, particularly of the new grade of ‘housemasters’ (also known as assistant governors). He believed that success in any organization was ‘dependent absolutely on the quality of the staff’ (Ruck 1951: 13). The result, over time was a significant shift in the character of borstal regimes. His aim was to reform, ‘reclaim’ and train those who found themselves in Borstals. Edwards and Hurley summarize the achievements as follows:

In 1924 uniform for borstal officers was abolished, and officers generally were encouraged to involve themselves with the boys in a wide variety of activities, many of them of a leisure time character. Summer camps became a feature of borstal life. The Commissioners’ annual report for 1929 foreshadowed a new borstal establishment to cope with the demands for places. This new establishment was inaugurated by the famous march undertaken in May 1930 by a group of staff and boys from Feltham borstal under the leadership of the governor W.W. Llewellin to found the first open prison establishment in England, at Lowdham Grange in Nottinghamshire. In 1935 Llewellin led a similar march from Stafford to Freiston near Boston, Lincolnshire, where a second open borstal, North Sea Camp, was established. A third was started in 1938 at Hollesley Bay, Suffolk. In 1936 adult prisoners from Wakefield slept in open conditions for the first time at New Hall Camp which was in continuous occupation from January 1937. These developments attracted no serious criticism from the public.

Having effected change within the borstal system, Paterson then sought to apply his principles to elements of the prison system. In particular, he looked at the experience of the ‘Star class’ of prisoner – adults imprisoned for their first offence. Part of Paterson’s success lay in the sheer length of time he was Commissioner. A further aspect lay in the connections he had made both at Oxford and through the networks associated with ‘Oxford in Bermondsey’. When this was added to his expertise with regard to the experiences of young men and his ability to choose and motivate those charged with the running of borstals. One of Paterson’s oft-quoted sayings was that the secret of discipline was motivation. ‘When a man is sufficiently motivated, discipline will take care of itself (see Ruck 1951)’. It was this plus concern with education and training rather than a focus on punishment that characterized his contribution. However, Alexander Paterson did recognize that some were ‘incorrigible’ and that society needed protection from such people (clauses in the Criminal Justice Act 1948 around preventive detention owed their existence largely to him).

Conclusion

Alexander Paterson was a man of considerable courage and charisma. He had a profound ability to inspire others and to call them to work on behalf of those less fortunate than themselves. Ruck (1951: 14) comments:

[H]e was not the empirical sentimentalist he was sometimes represented to be. At first a leader and man of action who happily brought to realization some preconceived ideas of reform, he was also a student and thinker.

He had faith in the value and potential of all, a faith that had been strengthened by his experience of living among poor people, and of serving in the trenches during the First World War. This capacity to join with people, to share in their lives, allowed him to develop a far more rounded appreciation of social questions than most within his class. His Christian faith provided the motor for action. The result was a contribution that spanned a number of fields – youth work, the needs and experiences of people in deprived areas, prison reform and establishment of Toc H.

Further reading and bibliography

Atlee, C. (1954). As it Happened, London: Heineman.

Baron, B. (1952). The Doctor. The story of John Stansfeld of Oxford and Bermondsey, London: Edward Arnold.

Bray, (1907). The Town Child, London: Fisher Unwin.

Eagar, W. McG. (1953). Making Men. The history of boys’ clubs and related institutions in Great Britain, London: University of London Press.

Edwards, A. and Hurley, R. (undated). ‘Prisons over two centuries’, The Home Office, http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/docs/prishist.html, accessed 24 September 2004.

Henriques, B. L. Q. (1937). The Indiscretions of a Warden, London: Methuen.

Hobhouse, S. and Brockway, A. F. (eds.) (1922). English Prisons Today: being the report of the Prison System Enquiry Committee, London: Longmans, Green.

Loewe, L. L. (1976). Basil Henriques. A portrait based on his diaries, letters and speeches as collated by his widow Rose Henriques, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Paterson, A. (1911). Across the Bridges or Life by the South London River-side, London: Edward Arnold.

Rice, J. and Prideaux-Brune, K. (1990). Out of A Hop Loft. Seventy-five years of Toc H, London: Darton, Longman and Todd.

Ruck, S. K. (ed.) (1951). Paterson on Prisons. The collected papers of Sir Alexander Paterson, London: Frederick Muller.

Secretan, H. (1931). London Below the Bridges. Its boys and its future, London: Geoffrey Bles.

Smith, C. (2004). ‘Sir Alexander Henry Paterson (1884-1947), Penal Reformer’ in H.Matthew (ed.) New Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wright, R. Selby (1951). Great Men. Being short impressions of ‘X,’ H. H. Almond, W. A. Smith, A. H. Stanton, Kingsley Fairbridge, Alexander Paterson. London: Epworth Press.

Urwick, E. J. (ed.) (1904). Studies of Boy Life in our Cities, London: Dent.

Links

How to cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2004, 2011, 2020) ‘Alexander (Alec) Paterson, youth work and prison reform, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [Available at https://infed.org/mobi/alexander-paterson-youth-work-and-prison-reform/. Retrieved: insert date].

Acknowledgement: The image of Alexander Paterson is reproduced by infed.org with permission from the National Portrait Gallery ccbyncnd3 licence mw121728

© Mark K. Smith 2004, 2011, 2020