Colin Ward: the ‘gentle’ anarchist and informal education. Often described as ‘Britain’s most famous anarchist’, Colin Ward’s political beliefs provoked and inspired his publications, as well as his long-held concern with place and social justice. Here, Sarah Mills explores the contribution of Colin Ward and the significance of his work for those involved in informal education.

contents: introduction · life, work and political thought · childhood and informal education · conclusion · bibliography and resources · references · how to cite this article

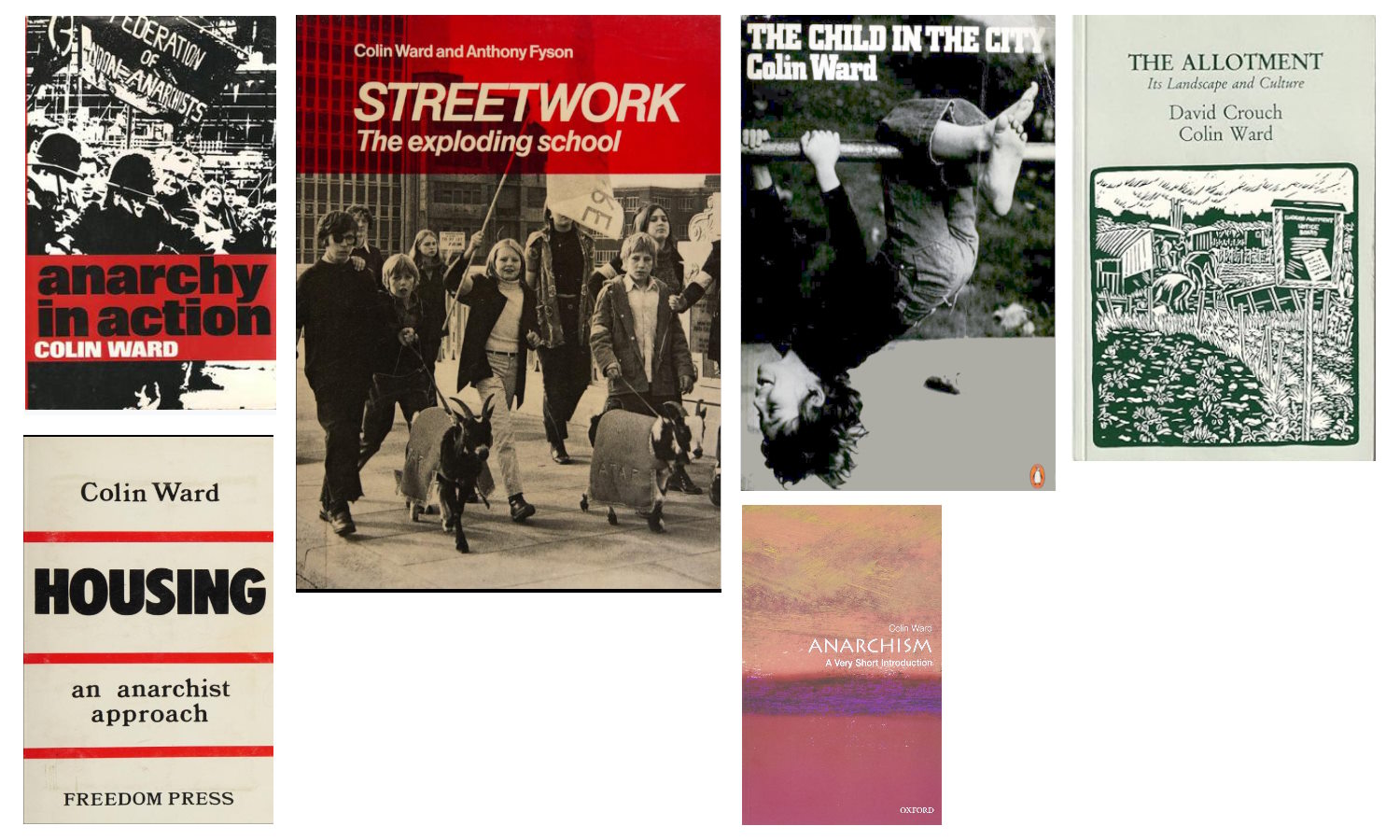

Colin Ward (1924-2010) has left a legacy of radical ideas grounded in direct action.These were communicated through a number of thought-provoking and in-depth social histories.Indeed, Ward’s political beliefs shaped his objects of enquiry and can be clearly seen running through his arguments. His interests were diverse: planning, camping, housing, allotments and, significantly, education. The contribution Colin Ward made in the context of informal education can be seen in his most famous pieces of work on children’s everyday lives and street culture in The Child in the City (1978) and The Child in the Country (1988). These, as well as other publications on school design and education ‘outside’ of the school, have inspired a number of academics in various disciplines to consider young people as a marginalised group and explore their lifeworlds.

Colin Ward (1924-2010) has left a legacy of radical ideas grounded in direct action.These were communicated through a number of thought-provoking and in-depth social histories.Indeed, Ward’s political beliefs shaped his objects of enquiry and can be clearly seen running through his arguments. His interests were diverse: planning, camping, housing, allotments and, significantly, education. The contribution Colin Ward made in the context of informal education can be seen in his most famous pieces of work on children’s everyday lives and street culture in The Child in the City (1978) and The Child in the Country (1988). These, as well as other publications on school design and education ‘outside’ of the school, have inspired a number of academics in various disciplines to consider young people as a marginalised group and explore their lifeworlds.

Life, work and political thought

Colin Ward was born in Wanstead, Essex in August 1924. After leaving school at fifteen, Ward worked as an architect’s draughtsmen until he was conscripted in 1942. This would prove a critical moment in Colin’s life as during his time with the British Army in World War Two, he became an anarchist. Infamously, a subscription to War Commentary led to Ward giving evidence in a trial of its three editors, who were eventually sentenced to nine months in prison on grounds of endorsing disaffection. After the war, Colin Ward began to write regularly for journals, with much of his early journalism focusing on the squatters’ movement. He subsequently became editor of Freedom, the British anarchist newspaper (1947-1960), eventually founding Anarchy and serving as its editor between 1961 and 1970. In 1973, Ward culminated his ideas and political thought in Anarchy in Action. Here, inspired by anarchists Peter Kropotkin and Gustav Landauer (see Baldwin, 1970; Esper, 1961), Ward outlined his theory of anarchism:

The argument of this book is that an anarchist society, a society which organizes itself without authority, is always in existence, like a seed beneath the snow, buried under the weight of the state and its bureaucracy, capitalism and its waste, privilege and its injustices, nationalism and its suicidal loyalties, religious differences and their superstitious separatism….Of the many possible interpretations of anarchism the one presented here suggests that, far from being a speculative vision of a future society, it is a description of a mode of human organization, rooted in the experience of everyday life, which operates side by side with, and in spite of, the dominant authoritarian trends of our society. (Ward, 1973: 11)

For Colin Ward, conceptions of ‘anarchy in action’ manifest themselves most clearly in the built environment. Inspired by his architectural training, he was interested in how ‘ordinary people’ self-motivated and self-designed spaces and communities. Colin continued as an architect in the late 1950s and 60s, and by the 1970s he was appointed Education Officer for the Town and Country Planning Association. These roles inspired Ward to publish about the relationships between architecture, planning and education. Most famously, The Child in the City (1978) explored the way in which children make creative use of urban environments. As Ward’s anarchist beliefs were rooted in everyday relationships and experiences, he also channelled these values into social histories of the quotidian practices of organisations, stressing the value of co-operation. For example, he praised organisations such as the RNLI, housing associations and worker’s co-operatives. This focus on the voluntary sector, and his belief in the everyday ways that individuals can galvanise social change through direct action, led to Ward being described as a ‘gentle’ anarchist proposing a ‘grassroots’ revolution. His later writings included social histories of holiday camps (1986, with Dennis Hardy) and allotment gardens (1988, with David Crouch), with the theme of ‘self-made’ communities most strongly communicated in Arcadia for All (1984, with Dennis Hardy). As well as ideas of self-organisation, Colin Ward was also interested in the potential of mutual aid. For example, writing in an introduction to Peter Kropotkin’s Fields, Factories and Workshops Tomorrow (1975), a book which Ward also edited and contributed to, he spoke of how ideas of self-sufficiency and mutual aid were relevant for the current economic and energy crises.

Colin Ward is quoted as saying that “all my books hang together as an exploration of the relations between people and their environment” (Worpole, 1999: 12) and this can be seen right through into his final publications, most powerfully in Cotters and Squatters (2002) – an examination of the rural poor that connects ideas of housing, architecture and everyday use of space. Indeed, it has been Ward’s focus on people’s relationships with their environments that gets to the heart of his writings, political beliefs and legacy. This perhaps ‘quiet’ or ‘banal’ aspect of study could easily be overlooked or dismissed, particularly when compared to other anarchist writings and ideology. However, it is the real connection to the experiences of everyday life that makes Ward’s contribution so powerful, relevant and timeless. Colin Ward died on 11th February 2010 aged eighty-five, survived by his wife Harriet, whom he married in 1966, and their children.

Childhood and informal education

One of Colin Ward’s greatest contributions was his focus on childhood and the built environment. This interest first appears in a chapter of Anarchy in Action (1973) – ‘Schools No Longer’ – where Ward discusses the genealogy of education and schooling, in particular examining the writings of Everett Reimer and Ivan Illich, and the beliefs of anarchist educator Paul Goodman. Many of Colin’s writings in the 1970s, in particular Streetwork: The Exploding School (1973, with Anthony Fyson), focused on learning practices and spaces outside of the school building. In introducing Streetwork, Ward writes, “[this] is a book about ideas: ideas of the environment as the educational resource, ideas of the enquiring school, the school without walls…” (1973: vii). In the same year, Ward contributed to Education Without Schools (edited by Peter Buckman) discussing ‘the role of the state’. He argued that “one significant role of the state in the national education systems of the world is to perpetuate social and economic injustice” (1973: 42). Here, we can again see the inter-relatedness between Ward’s own experiences, politics and writings. Ken Worpole, fellow writer and collaborator, reflects on this period of Colin’s work, which also included the initiation of a Bulletin of Environmental Education through the Town and Country Planning Association:

The point…was to help get children out of school and into their communities, to talk to local people, and explore their neighbourhood, its amenities and utilities, and understand how buildings, streets, landscapes and social life interact. This led to Colin’s focus on the unique world of childhood which, in the end, may prove to have been his – and anarchism’s – most enduring contribution to social policy. (Worpole, 2010)

Indeed, in The Child in the City (1978),and later The Child in the Country (1988), Ward examined the everyday spaces of young people’s lives and how they can negotiate and re-articulate the various environments they inhabit. In his earlier text, the more famous of the two, Colin Ward explores the creativity and uniqueness of children and how they cultivate ‘the art of making the city work’. He argued that through play, appropriation and imagination, children can counter adult-based intentions and interpretations of the built environment. His later text, The Child in the Country, inspired a number of social scientists, notably geographer Chris Philo (1992), to call for more attention to be paid to young people as a ‘hidden’ and marginalised group in society. Ward, however, was keen to stress the individuality of children and their educational needs, quoting cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead that “it’s a good thing to think about the child as long as you remember that the child doesn’t exist, only children exist, every time we lump them together, we lose something.” (1978: vi) Ward was also an educator himself as a teacher of Liberal Studies at Wandsworth Technical College in South London during the 1960s. This grassroots experience of education, including his work as an Education Officer, gave Ward’s writing an authoritative and yet sympathetic edge. This quality, combined with his passionate and long-held concern with the politics of place, makes Colin Ward an inspirational key thinker.

Conclusion

Colin Ward’s work displays an incredible range of subject matter. In some respects, his enquiries were disparate and on the surface unconnected, however, they were always linked by passionate enquiry and a very real concern into the relationships between places, environments and people. As a social historian, the rigour and clarity of his writing helped to bring the lifeworlds of children, allotment keepers, squatters and a variety of social groups to a mass audience. In examining how ordinary people developed ‘unofficial’ ways of using and adapting their environment, Colin Ward’s work has an endearing quality, and yet, his contribution to how we think about and conceptualise childhood and education resonates with contemporary debates. For example, the architectural design of schools, something Ward was writing about in the 1970s, continues to be a pervasive theme in the British government’s agenda for education and the way policy makers envision environments for young people. Ward also demonstrated the importance of acknowledging the variety of spaces that young people encounter that extends beyond the school, and significantly, their important role in social and political life in Britain.

Bibliography and Resources

Ward, Colin (1973) Anarchy in Action London: Allen & Unwin.

Ward, Colin and Anthony Fyson (1973) Streetwork: The Exploding School London: Routledge

Ward, Colin (1973) ‘The Role of the State’ in P. Buckman (Ed.) Education Without Schools London: Souvenir Press, 39-48.

Ward, Colin (Ed.) (1975) Peter Kropotkin Fields, Factories and Workshops Tomorrow Freedom Press.

Ward, Colin (1976) (eds) British School Buildings: Designs and Appraisals 1964-74 London: Architectural Press.

Ward, Colin (1978) The Child in the City with photographs by Ann Golzen and others. London: Architectural Press

Ward, Colin and Dennis Hardy (1984) Arcadia for All London: Mansell Publishing

Ward, C. and Dennis Hardy (1986) Goodnight Campers! History of the British Holiday Camp London: Mansell Publishing

Ward, Colin (1988) The Child in the Country London: Hale

Ward, Colin and David Crouch (1988) The Allotment: its landscape and culture London: Faber

Ward, Colin (2002) Cotters and Squatters Nottingham: Five Leaves

Ward, Colin (2004) Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction

Colin Ward at The Anarchist’s Library – http://www.theanarchistlibrary.org/authors/Colin_Ward.html

References

Baldwin, R. N. (1970) ‘The Story of Kropotkin’s Life’ in P. Kropotkin Anarchism: A Collection of Revolutionary Writings [1927] Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1970.

Esper, T. (1961) The Anarchism of Gustav Landauer Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Philo, C.(1992) ‘Neglected rural geographies: a review’, Journal of Rural Studies 8 (2): 193-207

Worpole, K. (1999) (eds) Richer futures: fashioning a new politics London: Earthscan Ltd

Worpole, K. (2010) ‘Colin Ward Obituary’ Guardian Online, http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/feb/22/colin-ward-obituary22nd February 2010

How to cite this article: Mills, S. (2010) ‘Colin Ward: The ‘Gentle’ Anarchist and Informal Education’ The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education.[https://infed.org/mobi/colin-ward-the-gentle-anarchist-and-informal-education].