Derek Gillard provides notes on the historical context and membership of the Consultative Committees chaired by Sir William Henry Hadow, summarises each of the six reports produced between 1923 and 1933, and assesses the extent to which their recommendations informed the development of education in England.

contents: background – historical context, membership of the hadow committees · summaries of the hadow reports – 1923: differentiation of the curriculum for boys and girls, 1924: psychological tests of educable capacity, 1926: the education of the adolescent, 1928: books in public elementary schools, 1931: the primary school, 1933: infant and nursery schools · conclusions – structures, curriculum, legacy · bibliography · links · how to cite this article

link: the full texts of the Hadow Reports can be found on Derek Gillard’s website.

As England began to develop its state system of schools towards the end of the nineteenth century, education became a matter for serious enquiry and debate and government-appointed consultative committees were set up to report on many aspects of the project.

In 1896, for example, a committee was asked to look into the question of the registration of teachers. Ten years later another committee reported ‘upon questions affecting higher elementary schools’. From then on, reports came thick and fast. The 1908 Report of the Consultative Committee upon school attendance of children below the age of five was followed by reports on Attendance, compulsory or otherwise, at continuation schools (1909), Examinations in secondary schools (1911), Practical work in secondary schools (1913) and Scholarships for higher education (1916).

After that, the First World War forced the suspension of the consultative committee until July 1920. Its report on The differentiation of the curriculum for boys and girls, published in 1923, was to be the first of six reports produced under the chairmanship of Sir William Henry Hadow. These reports – totalling 1,500 pages, around 650,000 words – covered all stages of schooling from the nursery to the school leaving age.

Membership of the Hadow committees

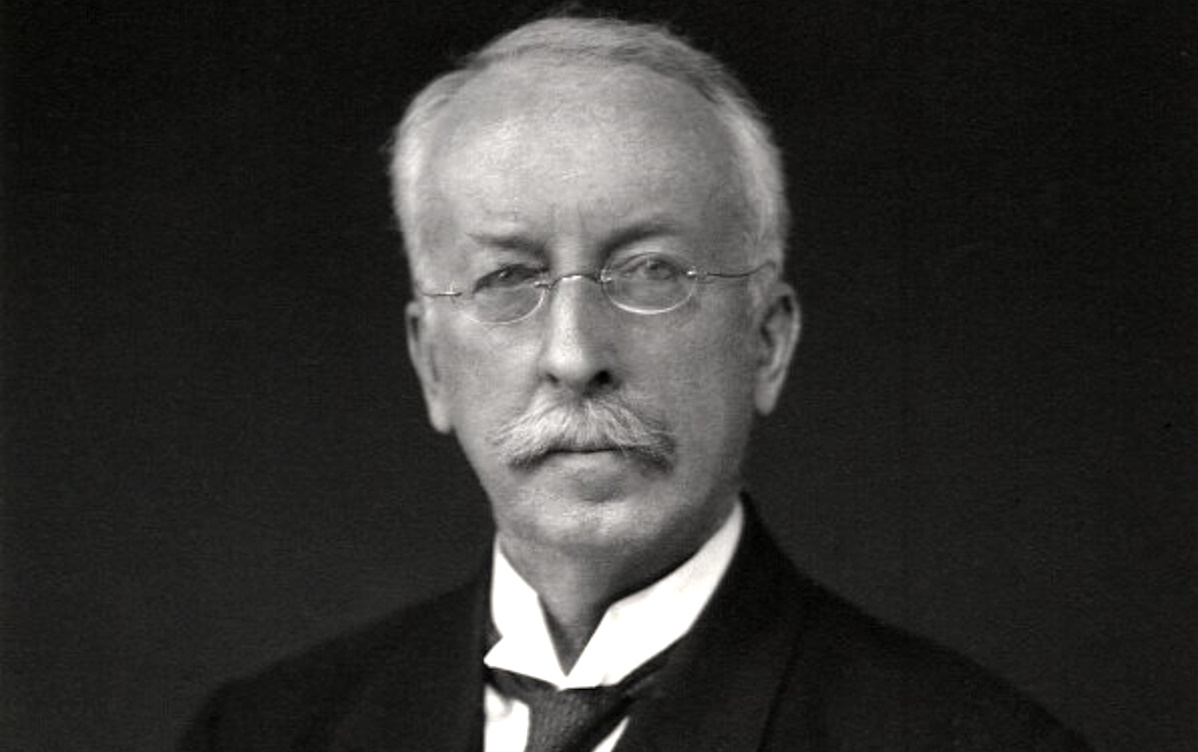

Sir W. H. Hadow (1859 – 1937). (William) Henry Hadow was educated at Malvern School and Worcester College Oxford. In 1894 he became a Delegate of the Oxford Locals; Proctor in 1898, and an examiner in 1900. In 1909 he was appointed Principal of Armstrong College Newcastle, and in 1919 he became Vice Chancellor of the University of Sheffield, where he remained until 1930.

William Henry Hadow held many other posts, including lectureships in Glasgow and Cambridge; he was a member of the Royal Commission on University Education in Wales, and chaired the Archbishops’ Commission on Religious Education. He was awarded a knighthood in 1918 and the CBE in 1920.

Hadow produced several books on educational issues, including Citizenship (1923) and Landmarks in education (1927). He also wrote widely on music and was awarded honorary DMus degrees by the universities of Oxford, Durham and Wales. (Information from Who’s Who 1931).

Other members. Forty-two people served on the six Hadow committees, including Hadow himself and R. F. Young, who was secretary for all the reports. About half this number served on any one committee.

Among these were Dr J. G. Adami (1862-1926), who came to public notice in 1888 when he exposed himself to rabies and published an account of his treatment at the Pasteur Institute’s vaccination clinic. After working in Canada for twenty-five years, he returned to England and was Vice Chancellor of Liverpool University from 1919 until his death.

Dr Albert Mansbridge (1876-1952) was one of the founders of the Workers’ Educational Association and wrote An adventure in working class education, being the story of the Workers’ Educational Association 1903 – 1915 (1920).

A. J. Mundella was presumably (though I’ve not been able to verify this) the son of Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897), the Liberal MP for Sheffield Brightside after whom the 1880 Education Act (The Mundella Act) was named. This A. J. Mundella appears also to have been politically active, writing about unemployment in Labour exchanges and education (1910).

Richard Henry Tawney (1880-1962) spent thirty years at the London School of Economics, becoming Professor of Economic History in 1931.

Although not a member of the consultative commmittees, Professor Sir Cyril Burt (1883-1971) contributed much information and advice, especially for the 1924 Report on Psychological tests of educable capacity. Among other appointments he was Psychologist to the Education Department of London County Council from 1913 to 1932; Professor of Education at the University of London from 1924 to 1931; and Professor of Psychology at University College London from 1931 to 1950. His views on intelligence have long since been discredited.

Summaries of the Hadow reports

For historians, the Hadow reports are invaluable documents. They not only paint a vivid picture of schools and the society in which they operated in the early twentieth century, but as each one begins with a historical chapter, they also provide a wealth of information about life and schooling in the nineteenth century.

The best known of the reports – The Education of the Adolescent (1926) and The Primary School (1931) – are particularly worth delving into. There are clear pre-echoes of Plowden here – many of the views expressed are surprisingly progressive. The 1931 report, for example, suggests that a good school ‘is not a place of compulsory instruction, but a community of old and young, engaged in learning by cooperative experiment’. (1931: Introduction) It goes on to argue that ‘the curriculum of the primary school is to be thought of in terms of activity and experience rather than knowledge to be acquired and facts to be stored’. (1931: Section 75)

1923: Differentiation of the curriculum for boys and girls

This ‘Hadow report’ begins with a history of the curriculum, comparing that offered to boys with that in girls’ schools. It notes that ‘the girls’ curriculum in its existing form is only about sixty years old, whereas the boys’ curriculum represents the outcome of centuries of development’.

The existing curriculum is seen as too academic, over-burdened and rigid. More attention should be paid to the ‘aesthetic side’ of secondary education and there should be an acknowledgement of ‘the proper place of domestic subjects (including elementary hygiene) in the girls’ curriculum’.

Differences between boys and girls in terms of anatomy, physiology, social environment and function are explored.

The report lists 24 recommendations. It argues for greater freedom in the curriculum for both boys and especially girls; for more time for pupils to develop their own individual interests, and for the relaxation of some university matriculation requirements.

It argues for a greater emphasis on aesthetic subjects for both boys and girls; better provision of maths and physics teaching in girls’ schools; and greater priority for English teaching in boys’ schools.

This Hadow committee was clearly anxious about the pressures on girls. The report recommends that there should be fewer external examinations; that girls should be protected from ‘physical fatigue and nervous overstrain’; and that they should be required to do less homework in view of ‘the relatively heavy domestic duties often performed by them in their homes’.

It urges that further research should be undertaken into the relative susceptibility of boys and girls to mental and physical fatigue, and into the intellectual and emotional differences between the sexes and their implications for the curriculum.

The report concludes that ‘the various subjects of the curriculum should be taught in closer correlation with one another’; that school work should be more practical; and that women should be ‘adequately represented on all committees and examining bodies which deal in any way with girls’ education’.

1924: Psychological tests of educable capacity

This ‘Hadow report’ begins with a long and detailed history of the development of psychological tests, and draws some some negative conclusions about earlier methods. It describes tests of higher mental processes and the diagnosis of mental deficiency, the various revisions of the Binet-Simon Scale, group tests, performance tests, standardised tests of scholastic attainment, and tests of vocational aptitude, temperament and character.

It summarises the available evidence ‘bearing on the problems connected with the various types of psychological tests of educable ability’, asks what tests of intelligence actually measure, and assesses the value of standardised scholastic tests and vocational tests in determining educable ability.

It considers the possible applications of psychological tests in the public education system. It notes that teachers, school doctors and others need training in using such tests, and argues that psychologists, teachers and statisticians need to cooperate in applying psychological and statistical methods to education.

The nine appendices include notes by Dr Cyril Burt, comments from psychologists on the factors involved in ‘general’, ‘special’ and ‘group’ abilities, and some examples of psychological tests.

The committee does not appear to be have been entirely convinced of the value of widespread testing. It recommends that only ‘recognised experts’ should devise and interpret the tests and that such experts ‘should take counsel with those who are in close touch with school life’.

Intelligence tests, it says, ‘are of value as supplements to, but not as substitutes for, the present methods of estimating individual capacity’. In particular, it warns that ‘no child should ever be treated as mentally deficient solely on the evidence afforded by the application of “intelligence” tests’.

It dismisses tests of memory, perception and attention as ‘of little use to teachers’, physical tests as ‘of very little use to teachers’ and tests of temperament and character as ‘practically useless to teachers’.

Finally, the committee urges ‘that the Board of Education … should set up an advisory committee to work in concert with university departments of psychology and other organisations engaged in the work of research’.

1926: The education of the adolescent

The report presents a sketch of the development of post-primary education in England and Wales from 1800 to 1918. It analyses ‘the nature of the problem’ of post-primary education, presents a statistical summary, and notes the steps taken by local education authorities to deal with the problem.

It goes on to suggest some ‘lines of advance’, urging a ‘regrading of education’ to provide ‘a fresh classification of the successive stages of education before and after the age of 11+’. It recommends the use of the terms ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ education.

This ‘Hadow report’ stresses ‘the importance of planning the curriculum as a whole and of ensuring that the various subjects … are taught in relation to one another’; ‘the desirability of bringing the curriculum into relation with the local environment’; and ‘the educational significance of giving pupils in the last years of school life a certain amount of work bearing in some way upon their probable occupations’.

It considers a range of other issues, including the question of vocational ‘bias’ in the curriculum, staffing and equipment, the admission of children to secondary schools, ‘the lengthening of school life’, examinations, and the potential administrative problems involved in changing to the proposed new structure of primary and secondary education.

The five appendices include notes on educational nomenclature; statistics; a survey of the provision of post-primary education abroad, and a list of publications.

The report recommends that primary education should end at the age of 11+ and that all ‘normal children’ should go forward to some form of ‘secondary education’.

In non-selective schools there should be an emphasis on ‘opportunities for practical work … closely related to living interests’ and staffing ratios in these schools should be at least as favourable as those in grammar schools.

The school leaving age should be raised to 15+, if possible by 1932, and new forms of leaving examinations should be developed. The structure of local education authorities should be rationalised to take account of the new arrangements.

1928: Books in public elementary schools

The report begins with a historical survey of the provision of books in elementary schools from 1810 to the 1920s. It examines the function of books in schools and assesses the volume, quality and character of the current supply in relation to the various curriculum areas.

It reviews the practices and methods of various local education authorities, notes the range of different libraries provided by local authorities, and assesses the sources of guidance available for teachers in the choice of books. It considers questions relating to the production of books for schools, their cost and their use both at school and in the home.

The six appendices include notes on the practice of some local education authorities and a comparison of expenditure on books in various areas.

The report lists 43 recommendations. It urges greater expenditure on books for schools, especially in those areas where it is ‘seriously insufficient’. Every school should have at least one library, with ‘adequate accommodation’ and good quality books. ‘The children should learn from them to admire what is admirable in literature, and to acquire a habit of clear thought and lucid expression.’

Recommendation 33 is revealing of the committee’s progressive and generous attitudes: ‘every pupil should be allowed, at least in school, to retain possession of all the books which he is constantly using, and that they should remain in his keeping until the end of the term or year in which he requires them … older scholars from the age of 11 and upwards should in addition be encouraged to take books home … books on certain subjects in which individual pupils have displayed special aptitude or interest might, towards the end of their school life, be given to them as a privilege or reward.’

The report urges better training for teachers in the selection of books, and recommends that a Central Advisory Conference should be established to advise on the supply, quality and content of books for schools.

1931: The primary school

After a ‘history of the development of the conception of primary education above the infant stage’, the report describes the physical and mental development of children between the ages of 7 and 11, which, it concludes, should be the age range for the upper stage of primary education.

It reviews the curriculum and organisation of primary schools and considers provision for ‘retarded’ children. It includes chapters on staffing and teacher training; premises and equipment; and on examinations.

The three appendices include memoranda by H. A. Harris and Cyril Burt on the anatomical, physiological and mental characteristics of seven to eleven year olds.

In this Hadow report’s 70 recommendations, the writers argue for separate infant schools wherever possible but urges close cooperation between infant and junior schools. They stress that ‘the needs of the specially bright and of retarded children should be met by appropriate arrangements’.

The report argues that the primary curriculum should be ‘thought of in terms of activity and experience, rather than of knowledge to be acquired and facts to be stored’. It favours the ‘project’ approach. ‘The traditional practice of dividing the matter of primary instruction into separate “subjects”, taught in distinct lessons, should be reconsidered’, it says, subject to the rider that ‘provision should be made for an adequate amount of “drill” in reading, writing and arithmetic’.

No primary class should contain more than 40 children. Teacher training courses should be adjusted ‘to suit the new organisation of schools’, should ‘afford adequate practice in methods of individual and group work’ and should train teachers to cope with the special needs of retarded children.

There are recommendations regarding buildings, equipment, libraries and playing fields.

Seven year olds should be assessed on entry to junior schools, but ‘classification of these young children should be regarded as merely provisional, and should be subject to frequent revision’. The report looks forward to a time when examinations at 11 for selective secondary education will be unnecessary, or at least diminished. For the time being, however, it recommends tests in English and arithmetic plus ‘carefully devised group intelligence tests’, though it warns that ‘in our opinion it would be inadvisable to rely on such tests alone’. Continuous records should be kept of each child’s progress, and parents should be given termly or annual reports.

1933: Infant and nursery schools

This ‘Hadow report begins with a history of infant education and then reviews current knowledge about the physical and mental development of children up to the age of seven. It gives an account of the prevailing age limits and organisation of infant education, and examines the education of children below the age of five.

It considers the staffing of infant and nursery schools and the training of teachers for them; and reviews the needs of schools in terms of premises and equipment.

The six appendices include memoranda on the anatomical and physiological characteristics of 2-7 year olds by HA Harris and on their emotional development by Cyril Burt and Susan Isaacs.

The report lists 105 recommendations – the largest number of any of the Hadow reports. It endorses the existing age limits for compulsory and voluntary school attendance; recommends that children should transfer from infant to junior classes around the ages of eight; and that, wherever possible, separate infant schools should be provided. It stresses, however, that the primary stage of education ‘should be regarded as a continuous whole’.

It emphasises the importance of detecting ‘early signs of retardation’ but disapproves of retarded children being taught in separate schools at this early age.

It urges the provision of an ‘open air environment’ affording ‘scope for experiment and exploration’. The infant school curriculum should, like that of the primary school, be thought of in terms of activity and experience’ rather than knowledge and facts. Practical and physical activities should be paramount. ‘The child should be put in the position to teach himself, and the knowledge that he is to acquire should come, not so much from an instructor, as from an instructive environment.’ Freedom and individual work are ‘essential’ for the children, and ‘freedom in planning and arranging her work is essential for the teacher if the ever present danger of a lapse into mechanical routine is to be avoided’.

The nursery school, it says, ‘is a desirable adjunct to the national system of education; and … in districts where the housing and general economic conditions are seriously below the average, a nursery school should if possible be provided’.

No infant class should have more than 40 children, and, where practicable, all the teachers should be certificated. Nursery teachers should have appropriate training and ‘helpers’ should be provided to assist them.

‘Semi-open-air buildings’ and ‘garden playgrounds’ should be provided to secure ‘the essential conditions of fresh air, sunshine and light’.

Conclusions

The most important recommendations of the Hadow committees related to the structure of the school system and the curriculum. To what extent did these recommendations inform the development of education in England in the following decades?

Structures

The recommendations about the structure and nomenclature of schools were certainly influential, though it would be many years before they were fully implemented.

Early years. The committee urged the provision of nursery education. A nursery school, it said, ‘is a desirable adjunct to the national system of education; and … in districts where the housing and general economic conditions are seriously below the average, a nursery school should if possible be provided’. (1933: Recommendation No. 72) Forty years later Plowden noted that ‘the under fives are the only age group for whom no extra educational provision of any kind has been made since 1944 … Nursery education on a large scale remains an unfulfilled promise’. (1967:291)

Regrading. Education, the committee said, should be ‘regraded’, i.e. divided into two distinct phases to be called primary and secondary, with the break between the two at the age of 11+. (1926:87) This did eventually happen, though it took a long time. Primary schools became government policy from 1928, but the complete ‘regrading’ of the country’s schools into primary and secondary had to wait until the 1944 Education Act, and it was not until the mid 1960s that all children were educated in separate primary schools.

School leaving age. From 1932, all children should stay at school until at least the age of 15. (1926:168). Legislation to raise the school leaving age to 15 was introduced in 1929 but defeated. It was agreed in 1936 that the age would be raised in September 1939 but the outbreak of war forced a further postponement. Finally, the 1944 Education Act set the leaving age at 15, and it was eventually implemented in April 1947 – 21 years after Hadow’s recommendation.

Curriculum

The Hadow committees demonstrated some surprisingly progressive attitudes in relation to the curriculum. There was no perfect curriculum, they argued. The job of teachers and educationists was constantly to ask questions and seek to find better answers. ‘The problems of curriculum, by their nature, do not admit of any final solution; each generation has to think them over again for itself.’ (2300: Note) The curriculum ‘should be planned as a whole in order to avoid overcrowding’; it should arouse interest while ensuring ‘a proper degree of accuracy’; and it should be planned ‘with a due regard to local conditions, and to the desirability of stimulating the pupils’ capacities through a liberal provision of opportunities for practical work’. (1926:106)

Many of the committee’s recommendations – restructuring the primary curriculum in terms of projects, focusing on children’s interests, the use of discovery methods and the importance of collaborative work – would reappear forty years later in Plowden.

Projects. The committee saw advantages in thinking of the primary curriculum in terms of projects or topics which would appeal to children’s interests, rather than as a set of discrete subjects. ‘Teaching by subjects is a mode of instruction which … does not always correspond with the child’s unsystematised but eager interest in the people and things of a world still new to him … what is needed, therefore, is a new orientation of school instruction which shall bring it into closer correlation with the natural movement of children’s minds.’ (1931:83) Plowden reiterated this view: ‘The topic cuts across the boundaries of subjects and is treated as its nature requires without reference to subjects as such. At its best the method leads to the use of books of reference, to individual work and to active participation in learning.’ (1967:540)

Discovery. Project work should encourage children to solve problems and make discoveries for themselves. ‘The project would provide many openings for independent enquiries by children who might be attracted specially in one direction or another, or could bring special gifts, e.g. in drawing or modelling, to the illustration of particular points.’ (1931:84) And again, ‘The principle underlying the procedure of the infant school should be that, as far as possible, the child should be put in the position to teach himself, and the knowledge that he is to acquire should come, not so much from an instructor, as from an instructive environment.’ (1933:100) Plowden agreed: ‘The sense of personal discovery influences the intensity of a child’s experience, the vividness of his memory and the probability of effective transfer of learning.’ (1967:549)

Collaborative work. It should also involve collaborative group work. ‘The work would take largely the form of cooperation between a group of children, all of whom would find they had something to learn from the work of their fellows.’ (1931:84)

Child-centred. The committee was in favour of what would today be described as a child-centred approach to education. ‘Even in a single school may be found a wide range of types of mind and of conditions of environment’. The construction of curricula, therefore, was ‘not a simple matter’: ‘uniform schemes of instruction are out of the question if the best that is in the children is to be brought out’. (1926:103) Plowden took up this theme: ‘At the heart of the educational process lies the child. No advances in policy, no acquisitions of new equipment have their desired effect unless they are in harmony with the nature of the child.’ (1967:9)

A balanced approach. Hadow emphasised the need for a balanced approach. ‘There appear to be two opposing schools of modern educational thought, with regard to the aims to be followed in the training of older pupils. One attaches primary importance to the individual pupils and their interests; the other emphasises the claims of society as a whole, and seeks to equip the pupils for service as workmen and citizens in its organisation … When either tendency is carried too far the result is unsatisfactory.’ (1926:102) Plowden also urged balance: ‘We endorse the trend towards individual and active learning and “learning by acquaintance”, and should like many more schools to be more deeply influenced by it. Yet we certainly do not deny the value of “learning by description” or the need for practice of skills and consolidation of knowledge.’ (1967:553)

Reading. Hadow recommended the appropriate use of look and say, phonic, and sentence methods. ‘Each of these methods emphasises important elements in learning to read, and most teachers borrow something from each of them to meet the need of the moment or the special difficulties of different children.’ (1933:97) Forty years later Plowden would similarly note that ‘the most successful infant teachers have refused to follow the wind of fashion and to commit themselves to any one method’. (1967:584)

Writing. On writing, the Hadow committee urged that children should be ‘encouraged to express themselves freely’ and that spelling lessons should be based on the words the child actually uses, or on the literature s/he is reading. Children ‘should not learn lists of unrelated words. Any attempt to teach spelling otherwise than in connection with the actual practice of writing or reading is beset with obvious dangers’. (1931: Chapter 12, English) Again, Plowden said much the same: ‘In a growing number of junior schools, there is free, fluent and copious writing on a great variety of subject matter … To this kind of writing … we give an unqualified welcome.’ (1967:603) ‘The best writing of young children springs from the most deeply felt experience.’ (1967:605)

Broad, relevant and practical. For secondary pupils, the curriculum should be broad, relevant and practical and should include a foreign language. ‘A humane or liberal education is not one given through books alone, but one which brings children into contact with the larger interests of mankind … it should include a foreign language … and it should be given a ‘practical’ [i.e. vocational] bias only in the last two years.’ (1926:93)

Legacy

In the classroom. Hadow’s views on the curriculum were largely ignored and forgotten. The elementary school lived on, even if it was now called a primary school. These schools bore all the hallmarks of the elementary system ‘in terms of cheapness, economy, large classes, obsolete, ancient and inadequate buildings, and so on.’ (Galton, Simon and Croll 1980) They also continued to provide a curriculum based on the arid drill methods of the elementary schools, methods which were encouraged by the introduction of the 11+ exam for selection to secondary schools.

No wonder the Plowden committee felt the need to say it all again. Bridget Plowden wrote ‘we did not invent anything new’. (Plowden 1987) She was right. If Hadow’s recommendations had been implemented there would have been little need for Plowden, which reiterated much of what Hadow had said forty years earlier. Yet Plowden was still seen as dangerously progressive by many, especially the hacks of the tabloid press and the writers of the ‘Black Papers’. The educational backwoodsmen needn’t have worried. As Benford and Ingham pointed out, teachers had been ‘concerned to play safe rather than inspire’ and their inaction had ‘necessitated the translation of Hadow (1931) into Plowden (1967). Each was welcomed in its own time. Each was subsequently neglected where it mattered most: in the classroom.’ (Benford and Ingham The Times Educational Supplement 6 March 1987)

In national policy. Hadow’s recommendations concerning the structure of education were, as we have seen, eventually adopted by government and implemented. Its recommendations regarding the curriculum were not.

While progressive educational ideas had, by 1939, become the ‘official orthodoxy’ (Galton, Simon and Croll 1980), politicians showed little interest. This was no doubt partly because ministers had long been expected to keep out of the ‘secret garden’ of the curriculum. But all that changed in 1976 when Prime Minister Jim Callaghan gave a speech at Ruskin College Oxford which opened the ‘Great Debate’ about the purposes of education.

From then on, politicians decided that they knew all the answers and must impose their views on the nation’s teachers. Hadow’s plea that the teacher must have ‘freedom in planning and arranging her work’ so as to avoid ‘the ever present danger of a lapse into mechanical routine’ (1933:105) was rejected.

This process took a giant leap forward with the Thatcher government’s imposition of the National Curriculum in the 1988 Education ‘Reform’ Act and has been taken still further by Blair’s New Labour governments, which have dictated to teachers not only what they must teach but how they must teach it.

The latest example of this is the decision to force schools to teach reading by the ‘synthetic phonics’ method – a decision based on one small, flawed experiment in Clackmannanshire, much criticised by experts. So much for Hadow’s sound advice to use a range of methods and Plowden’s warning about following ‘the winds of fashion’. Politicians, as always, know best.

Both the Thatcher and Blair governments have been obsessed with testing children and compiling league tables of schools on the basis of the results. Perhaps it is appropriate, therefore, to end with two warnings from Hadow:

‘The conception of the primary school and its curriculum must not be falsified or distorted by any form of school test whether external or internal.’

‘We cannot too strongly deprecate the tendency to base a comparative estimate of the efficiency of schools upon the class lists of a selective “free place” examination.’ (1931:112)

Now almost eighty years on, it would be good to have a government which noted the wisdom of these words and acted upon them.

The Hadow committees started from where people were and based their opinions on the facts as they were then understood. The reports were, to that extent, products of their age – something that is especially evident in their attitudes to gender issues and special educational needs.

But they were extraordinarily optimistic: ‘We cannot but feel – as we unanimously do – that the times are auspicious, and the signs favourable, for a new advance in the general scope of our national system of education.’ That advance encompassed a vision of a future in which all children would enjoy ‘the free and broad air of a general and humane education’. (1926: Introduction)

It was a vision in stark contrast to the sterile, utilitarian, test-driven curriculum which politicians have now imposed on the nation’s schools.

References

Galton, M., Simon, B. and Croll, P. (1980) Inside the Primary Classroom (The ORACLE Report) London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Plowden, B. (1987) Plowden’ twenty years on, first published in the Oxford Review of EducationVol. 13 No. 1 1987.

Links

Derek Gillard’s website includes a longer version of this article and the full texts of all the Hadow Reports and the Plowden Report.

Derek Gillard taught in primary and middle schools in England for more than thirty years, including eleven as a head teacher. He retired in 1997 but continues to write on educational issues for Forum magazine and his own website.

The photograph of Sir William Henry Hadow was taken by Walter Stoneman (1876-1958) and is reproduced here with the permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London [NPG x168028] | ccbyncnd3 licence.

How to cite this article: Gillard, D. ‘The Hadow Reports: an introduction’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, www.infed.org/schooling/hadow_reports.htm.

© Derek Gillard 2006