Henrietta Barnett, social reform and community building. Henrietta Barnett is, perhaps, best known for the development of Hampstead Garden suburb, but she – with Samuel Barnett – was an important social reformer. Their most notable innovation was the university settlement – but they were also active in other arenas.

contents: introduction and life · toynbee hall · practicable socialism and social reform · henrietta barnett, hampstead garden suburb and community building · conclusion · further reading and references · how to cite this article

Introduction and life

Dame Henrietta Octavia Weston Barnett (née Rowland) (1851-1936) was born in Clapham, London. Her mother died soon after her birth and she was raised in some comfort by her father. She was educated at home until aged 16 when she spent several terms at a boarding school in Dover run by the Haddon sisters. Significantly, the sisters had a strong commitment to social altruism (Koven 2004). After her father’s death in 1869, Henrietta moved with two of her two sisters to Bayswater. She became involved in parish visiting and began to commit a significant amount of her time helping the social and housing reformer Octavia Hill. Hill was at this time developing her distinctive approach to housing provision and community-building (having begun in 1864 with three slum properties bought for her by John Ruskin).

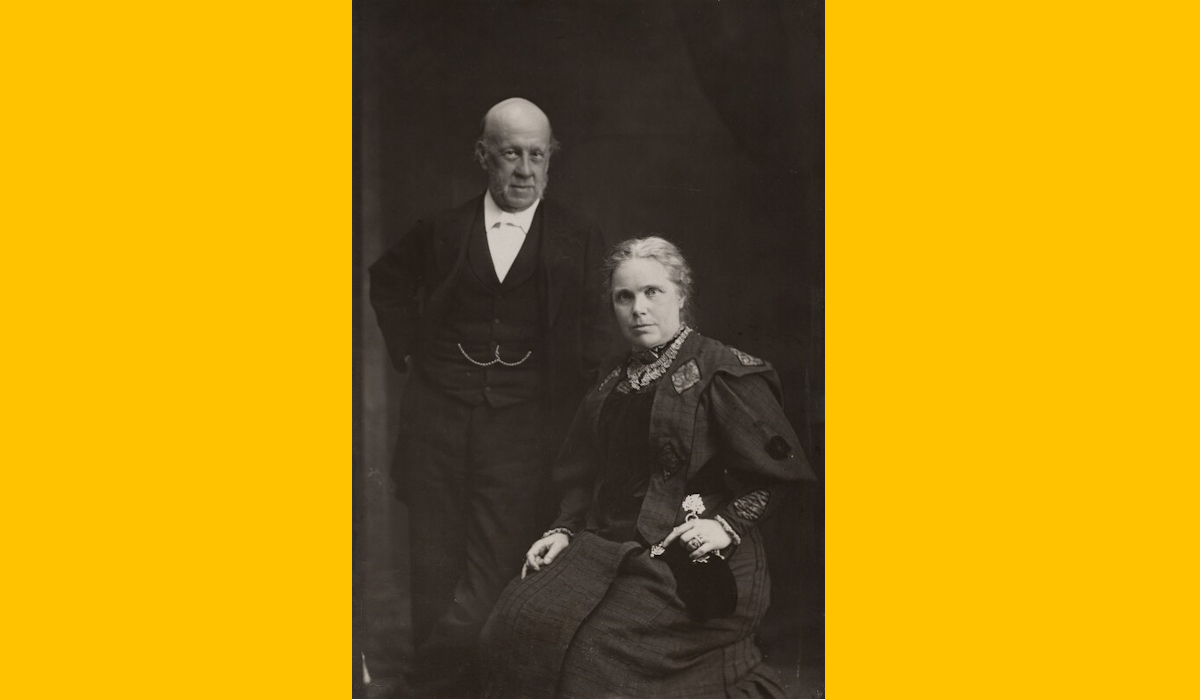

It was also through Octavia Hill that Henrietta was introduced to Samuel Augustus Barnett (the curate of St Mary’s, Bryanston Square and another co-worker of Hill). While they were different in temperament, their commitment to social action and reform drew them together. They were married in 1873 and went to live and work in the troubled and deprived parish of St Jude’s, Whitechapel.

Henrietta Barnett quickly turned again to parish visiting, and to developing work with women and children. She was an energetic and determined organizer and soon managed to attract a group of women to help her. Along with many other Victorians, Henrietta Barnett valued the role women played as mothers and ‘women’s distinct moral gifts as peacemakers capable of diffusing class war’ (Koven 2004: 1024). She also became a woman guardian for the parish (1875) and a school manager for the poor law district schools in Forest Gate (1876). Around the same time, Henrietta Barnett began a series of social initiatives including helping to set up the Metropolitan Association for the Befriending of Young Servants (1876), and experimenting with sending local slum children for country holidays. These efforts were later to grow into the Country Holiday Fund (established in 1877). By 1884 Henrietta and Samuel Barnett were working hard to set up the pioneering university settlement that became known as Toynbee Hall (see below).

For much of her later life (from around 1903 onwards) Henrietta Barnett concentrated upon creating the Hampstead Garden suburb. Henrietta and Samuel Barnett had moved to Hampstead in 1889 (Heath End House on Spaniards Road). Building on her experiences of working with Octavia Hill, and in east London, and looking to the work of Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker with regard to Letchworth Garden City, Henrietta Barnett wanted to create a community that was organic, mixed and that had housing and social amenities that allowed for a healthy life for all. She had a strong vision of what she wanted – and as she grew older (and after Samuel Barnett died) she became more driven and didn’t brook opposition (Slack 1982).

Alongside all this activity, Henrietta Barnett also produced a significant number of books and essays. These included books on domestic economy (The Making of the Home 1885), physiology (The Making of the Body 1894), and social reform (Practicable Socialism 1888, Towards Social Reform 1909 – both with Samuel Barnett).

Samuel Barnett died in 1913. Henrietta continued to be focused on her work in Hampstead, but she also supported Barnett House at Oxford (1914) which was named in memory of Samuel (and was the centre for social work and social policy education at the university). She also worked on an account of Samuel Barnett’s life and work: Canon Barnett: his life, work and friends (1918) and a collection of essays: Matters that matter (1930).

The Barnetts were never to have children of their own. Henrietta, however, was the legal guardian of her elder sister Fanny (who was brain-damaged) and Dorothy Woods (an adopted ward). Henrietta Barnet died in her Hampstead home in 1936.

Toynbee Hall and the emergence of university settlements

The Whitechapel parish of St Judes was well known for its appalling housing conditions, poverty and overcrowding. Samuel and Henrietta Barnett’s early work stressed self-help (Samuel Barnetts’ in a fairly extreme form in the matter of alms). Samuel Barnett campaigned for better housing conditions for the poor (and with parish workers from St Judes established model dwellings (1888); and the Children’s Country Holiday Fund (1877). Henrietta Barnett was an active partner in this activity – and in the discussions and networking that led to the establishment of Toynbee Hall (Watkins 2005).

A simple idea lay at the heart of the Toynbee Hall settlement: that all should share in community. If men and women from universities lived for some time among the poor in London and in other cities, they could ‘do a little to remove the inequalities of life’ (Samuel Barnett 1884: 272). They would share ‘their best with the poor and learn through feeling how they live’ (op. cit.). Through working for friendship based on trust, and government inspired with ‘a higher spirit’, ‘everything which is Best will be made in love common to all’ (ibid.: 273).

A settlement is simply a means by which men or women may share themselves with their neighbours; a club-house in an industrial district, where the condition of membership is the performance of a citizen’s duty; a house among the poor, where residents may make friends with the poor. (Barnett 1898: 26)

It was in this spirit that Toynbee Hall, the first university settlement was established in 1884.

The settlement was named after Arnold Toynbee (1852-1881), the Balliol historian. As well as undertaking university teaching Toynbee was committed to the development of adult education opportunities for the working class – and worked with Barnett in this area. He argued that the gap between social classes needed closing – and that those with money and education should spend time – and live – among the poor. That was the basic rationale for Toynbee Hall. The Barnett’s began with 16 settlers – and out of their efforts grew a significant social welfare and education programme. This has included adult education provision; youth work; various social work initiatives; housing; health provision and economic development. A number of associations began their lives here including the Worker’s Education Association (1903) (see, for example, Briggs and Macartney 1984; Meacham 1987; and Pimlott 1935).

Over the years the settlers have included some of the central figures in the development of welfare in this country: Clem Attlee (1883 – 1967) the Labour Prime Minister (1945-1951) was secretary to the Hall and an active social worker; Richard H. Tawney (1880 – 1962) who was central to the development of the Worker’s Education Association and to debates around social democratic thought began his residence here in 1903 working on the Holiday Fund. He was here until 1906 and came back for spells in 1908 and 1913. William Beveridge (1879 – 1963) the economist who wrote the crucial government report on social insurance (1942) was appointed sub-warden in 1903 (he left in 1905).

Henrietta Barnett’s advocacy of settlements, and more particularly a talk given to the Cambridge Ladies Discussion Society, also led to the proposal to establish the Women’s University Settlement in Southwark.

Practicable Socialism and social reform

Practicable Socialism appeared in 1888 and was, basically, a collection of pieces written separately by Henrietta and Samuel Barnett over the preceding 15 years. ‘They were written out of the fullness of the moment with a view of giving a voice to some need of which we had become conscious’ (Barnett and Barnett 1888: v). As such the essays do not set out to provide a systematic treatment of the area, but there are ‘two or three great principles’ underlying the reforms they advocate:

The equal capacity of all to enjoy the best, the superiority of quiet ways over those of striving and crying, character as the one thing needful are the truths with which we have become familiar, and on these truths we take our stand. (Barnett and Barnett op.cit)

The opening essays deal with the poverty of the poor, issues with regard to relief, and reformers misperceptions of those living in poverty. Henrietta Barnett was particularly concerned with the ways in which the vast numbers of people who, ‘while poor in money, are rich in life’s good, who live quiet, thoughtful, dignified lives’ (Barnett and Barnett 1888: 48) are forgotten and the focus put upon those she called ‘degraded poor’. She was critical of those who looked down upon ‘the poor’ – especially those claiming some Christian impulse. She was exasperated by their failure to grasp the nature of spirituality and the place it could have in people’s lives – and the extent to which they resorted to trying to cajole people away from sin with talk of hell, conditional offers of material help, or the provision of ‘exciting’ services and religion. ‘Dignity has given way to hurry, she comments (op. cit.: 53).

How can these degraded people be given these priceless gifts? The usual religious means have failed, the unusual must be tried; we must deal with the people as individuals, being content to speak, not to the thousands, but to ones and twos; we must become the friend, the intimate of a few; we must lead them up through the well-known paths of cleanliness, honesty, industry until we attain the higher ground whence glimpses can be caught of the brighter land, the land of spiritual life. (Barnett and Barnett 1888: 54)

Henrietta and Samuel Barnett turned in later chapters to explore the role of town councils and social reform, art for the people, the experiences of young women in workhouses, the church, charitable effort, and sensationalism in social reform. Samuel Barnett’s important piece on university settlements (first published in Nineteenth-Century in 1884) was also included.

The essay from which the book draws its title – Practicable Socialism – brings out some familiar ‘Barnett’ themes:

The study of political economy and some familiarity with the condition of the poor had shown us the harm of doles given in the shape either of charity or of out-relief. We found that the gifts so given did not make the poor any richer, but served to perpetuate poverty. We came therefore to East London determined to was against a system of relief which, ignorantly cherished by the poor, meant ruin to their possibilities of living an independent and satisfying life….

Facing, then the whole position, we see first the poverty of life which besets the majority of the people, and further we recognise that the remedy must be one which shall be practicable and shall not affect the sense of independence. (Barnett and Barnett 1888: 191; 195).

Julia Parker (1992: 1) has commented that Samuel Barnett has a special place in the history of British ethical socialism, ‘not so much as a thinker nor as a writer nor as a teacher but as a man who lived out his “practicable socialism” in the East End of London’. The same could conclusion could be applied in significant ways to Henrietta. While she and Samuel Barnett may well have placed limits on the extent to which liberty, equality and fraternity could, practically, order social relationships, they did believe that the, then current, situation fell far short of what was acceptable and that people could achieve significant social change.

Henrietta Barnett, Hampstead Garden suburb and community building

With the development of lands close to Hampstead Heath, and the proposed extension of the Northern Line to Golders Green and beyond, Henrietta Barnett realized that the character of the heath could be seriously damaged. She raised money to set about to buy the ‘Heath Extension’ to be preserved as parkland and worked to establish a new Garden Suburb. Her vision was of an estate built with architectural integrity and with people in mind. It was to be place in which ‘all classes could live in neighbourliness together with friendships coming about naturally and without artificial efforts to build bridges between one class and another’ (quoted by Slack 1982: 9). In 1904 the original Garden Suburb Trust was established to raise money to acquire some 243 acres of land. In 1906 in became known as the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust and one year later it had succeeded in obtaining the land, and had built the first two houses.

Henrietta Barnett worked with what one collaborator described as a ‘despotic masterfulness’ (quoted by Slack 1982). She wanted the development to work as a whole, to utilize the best architects, and to express harmony. To achieve this she went to Raymond Unwin and asked him to be the master planner of the new suburb. Unwin was, at the time, working on a similar project in Letchworth – the first garden city. Letchworth (some thirty miles north of London) was the physical expression of Ebenezer Howard’s thinking on town planning. His central idea, famously advanced in his book Tomorrow: A peaceful path to real reform (1898) was that towns should be a complete social and functional structure, limited in size (to around 32,000 people) and with enough jobs to make it self-sufficient (see Schaffer 1972: 22). In addition, it should be:

spaciously laid out to give light, air, and graciously living well away from the smoke and grime of the factories and surrounded by a green belt that would provide both farm produce for the population and opportunity for recreation and relaxation. Growth, design and density would be strictly controlled through public ownership of the land. (op. cit.)

Raymond Unwin was concerned to avoid uniformity and monotony. He used natural features and contours to shape the design. As a result, there was variety in the overall plan with the intimate moving to the grand; a refreshing use of open space and greenery; and the imaginative use of different architectural forms.

While there was a concern that people from different classes could mix, the design of the suburb separated different groupings – with the larger houses – often designed by leading architects – to the south and more vernacular designs for the skilled working classes to the north. No real provision was made for housing unskilled workers. As Hampstead Garden Suburb grew in popularity (partly fired by the nearness to the new tube station at Golders Green), a relative lack of social rented housing, and with housing prices increasing, it became a middle class enclave. As Kathleen Slack (1982: 42) has put it, the middle classes dominated the scene, occupied better houses and enjoyed domestic privileges.

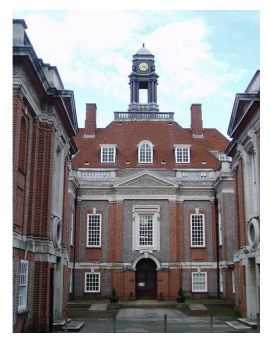

Just like Robert Owen in New Lanark, Henrietta Barnett wanted to place an Institute – a great educational and social centre – at the centre of the community. It was to be a house or home for learning. The range of activities was not as ambitious as Owen’s, and clearly harked back to the experience of Toynbee Hall. The first phase, designed by Lutyens opened in 1909. From the start there was a programme of lectures, literature and music rooms, and art and discussion groups. In 1911 Henrietta Barnett established a programme of education for girls school in the Institute which developed into the Dame Henrietta Barnett School on the site (the foundation stone was laid in 1918). The school was established on the basis that it should be open to girls from different backgrounds. However, it was, and remains, selective. The school was established on the basis that it should be open to girls from different backgrounds. However, it was, and remains, selective. The Institute still provides adult education programmes – but the selection is rather pedestrian compared to the early days.

Just like Robert Owen in New Lanark, Henrietta Barnett wanted to place an Institute – a great educational and social centre – at the centre of the community. It was to be a house or home for learning. The range of activities was not as ambitious as Owen’s, and clearly harked back to the experience of Toynbee Hall. The first phase, designed by Lutyens opened in 1909. From the start there was a programme of lectures, literature and music rooms, and art and discussion groups. In 1911 Henrietta Barnett established a programme of education for girls school in the Institute which developed into the Dame Henrietta Barnett School on the site (the foundation stone was laid in 1918). The school was established on the basis that it should be open to girls from different backgrounds. However, it was, and remains, selective. The school was established on the basis that it should be open to girls from different backgrounds. However, it was, and remains, selective. The Institute still provides adult education programmes – but the selection is rather pedestrian compared to the early days.

The Institute was just one part of the wonderful square that was designed in 1906-8 by Sir Edwin Lutyens as the centre of the suburb. Lutyens’ plans were never completed – but some substantial buildings were built including the Friend’s meeting house and St Jude’s Church.

Henrietta Barnett also succeeded in opening a number of other communal buildings including the club house situated by the original Artisans’ Quarter which was intended to provide a social focus without alcohol (there was also a tea house). It was bombed in 1940 and never rebuilt. A range of social care provision was also developed including children’s homes, a nursery training school and older people’s accommodation.

Conclusion

Henrietta Barnett’s was a formidable social innovator. Her vision, drive and focus helped to mount the major social experiment at Hampstead, and, with Samuel, to develop a landmark social form at Toynbee Hall. J. A. R. Pimlott described their marriage as ‘an historic event’. He continued:

Theirs was one of several partnerships of husband and wife which have contributed so notably to English public life… The Barnetts were complementary characters. Without his genius, she possessed a vigorous self-confidence and determination which, added to his qualities, made the combination fully equipped and wellnigh irresistible. (Pimlott 1935: 132)

Henrietta Barnett was a creature of her time and background. This meant that while Hampstead Garden Suburb was a significant physical achievement – and contained a number of interesting social innovations – it did not have the social mix, nor the social organization one might expect from the arguments of Practicable Socialism. Henrietta’s personality was such that she found it difficult to work democratically.

Further reading and references

Barnett, Henrietta (1885) The Making of the Home. A reading-book of domestic economy for school and home use. London: Cassell and Company.

Barnett, Henrietta (1894) The Making of the Body. A children’s book on anatomy and physiology : for school and home use. London: Longmans, Green.

Barnett, Henrietta (1918) Canon Barnett: His life, work and friends, 2 vols. London: John Murray.

Barnett, Henrietta (1930) Matters that matter. London: John Murray.

Barnett, S. A. (1894) ‘University settlements’ in S. A. Barnett and H. O. Barnett Practicable Socialism 2e, London:

Barnett, S. A. (1898) ‘University settlements’ in W. Reason (ed.) University and Social Settlements, London: Methuen.

Barnett, Samuel and Barnett, Henrietta (1888, 1915) Practicable Socialism. London

Barnett, Samuel and Barnett, Henrietta (1909) Towards Social Reform, London:

Briggs, A. and Macartney, A. (1984) Toynbee Hall. The first hundred years, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Creedon A. (2006). ‘Only a Woman’ Henrietta Barnett.Social Reformer and Founder of Hampstead Garden Suburb. Chichester: Phillimore.

Howard, Ebenzer (1898) Tomorrow: A peaceful path to real reform. London.

Koven, Seth (2004) ‘Dame Henrietta Octavia Weston Barnett’ in Matthew, H. C. G. and Harrison, B. (eds.) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meacham, S. (1987) Toynbee Hall and Social Reform 1880-1914. The search for community, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Parker, Julia (1992) ‘Canon Barnett: Ethical socialist’ in Colin Crouch and Anthony Heath (eds.) Social Research and Social Reform: Essays in hour of A. H. Halsey, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Pimlott, J. A. R. (1935) Toynbee Hall. Fidty years of social progress 1884 – 1934, London: Dent.

Schaffer, Frank (1972) The New Town Story. London: Granada.

Slack, Kathleen M. (1982) Henrietta’s Dream: A chronicle of Hampstead Garden Suburb 1905-1982, London:

Watkins, Micky (2005) Henrietta Barnett in Whitechapel. Her First Fifty Years. London: Hampstead Garden Suburb Archive Trust.

Unwin, Raymond (1909a) Town planning in practice : an introduction to the art of designing cities and suburbs. London.

Unwin, Raymond (1909b) Planning a Suburb and a Town. London.

Links

Hampstead Garden Suburb tour and history. The latter includes maps of Unwin’s layout, the historical background etc.

See Steve Cadman’s pictures of the suburb and the 600 or so pictures taken by ‘satguru‘.

Acknowledgements: the picture of the Hampstead Institute is by Steve Cadman and reproduced here under a Creative Commons Licence.

The picture of Henrietta Barnett and Samuel Barnett has been sourced from the National Portrait Gallery, London and is by Elliott & Fry, circa 1905 –

NPG x696 | ccncnd3 licence

How to cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2007, 2020) ‘Henrietta Barnett, social reform and community building’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/henrietta-barnett-social-reform-and-community-building/]

© Mark K Smith 2002, 2020.