Frances Herbert Stead, Robert Browning Hall and the fight for old age pensions. Frances Herbert Stead – often referred to as F. Herbert Stead (1857-1928) – was a Congregationalist minister who established and ran Robert Browning Hall and Settlement in Walworth, London). He was also a key figure in the fight for old age pensions in Britain. We explore his contribution both to the development of the settlement movement and to winning the old age pension.

Frances Herbert Stead, Robert Browning Hall and the fight for old age pensions. Frances Herbert Stead – often referred to as F. Herbert Stead (1857-1928) – was a Congregationalist minister who established and ran Robert Browning Hall and Settlement in Walworth, London). He was also a key figure in the fight for old age pensions in Britain. We explore his contribution both to the development of the settlement movement and to winning the old age pension.

contents: introduction · life · browning hall · frederick herbert stead, robert browning hall and the fight for pensions · conclusion · further reading and references · how to cite this piece

Francis Herbert Stead (1857-1928) made a major contribution both to the fight for state-provided old age pensions in Britain and to the development of the settlement movement. His work at Browning Hall, Walworth involved a distinctive social and political commitment. In addition, he wrote on a range of subjects most notably Social Christianity (Stead 1924) and church organization and operation (Stead 1889, 1892).

Life

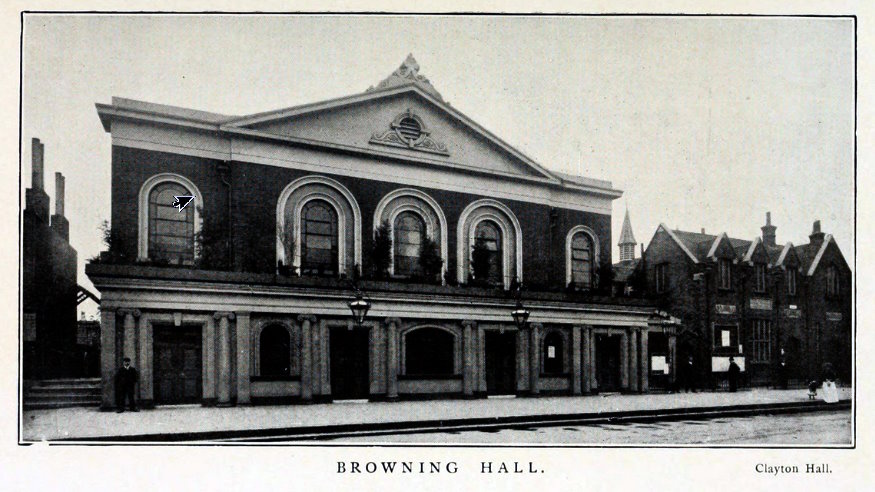

F. Herbert Stead was born in 1857 at Howden. He was the son of a minister. Like his brother – the journalist William Thomas Stead (1849-1912) who died when the Titanic sank – he too entered journalism but fairly quickly realized that his vocation lay elsewhere. He trained for the ministry at Glasgow University and went on to undertake further studies in Germany (Scotland 2007: 139). He then served as a minister at Gallowtree Gate Congregational Church, Leicester (1884-90) and during this time married Bessie Macgregor (they were to have four children). They then moved to London where Stead edited The Independent and Nonconformist for a couple of years. He also became the minister at the Browning Hall, Wandsworth. Formerly known as the York Street Chapel, it was built in 1790 and could seat 800 people. The poet and playwright, Robert Browning was baptized there in 1812 – and it was in the year after his death that the chapel was renamed in his memory. The building was demolished in 1978 and replaced by part of the Ben Ezra Court housing estate. [It was on the south side of what is now Browning Street (renamed 1937), to the west of Morecambe Street (Alan Patient undated)].

Influenced by the theology of F. D. Maurice and earlier Christian Socialists, F. H. Stead was committed to serving the needs of poor and working people – and to finding ways in which they could build and experience fellowship, engage in social action and change, and in so doing follow the example of Jesus. He believed that Christianity was essentially social:

Social relations are not, in the teaching of Jesus, secondary, derivative or accidental. They are not a temporary sphere for the conduct of the individual. They are the texture and fibre of the New Life. The very purpose of Jesus was to found a Community – a Community which should fulfil and surpass the noblest dreams of Hebrew prophecy. (Stead 1924 [volume 1]: xi)

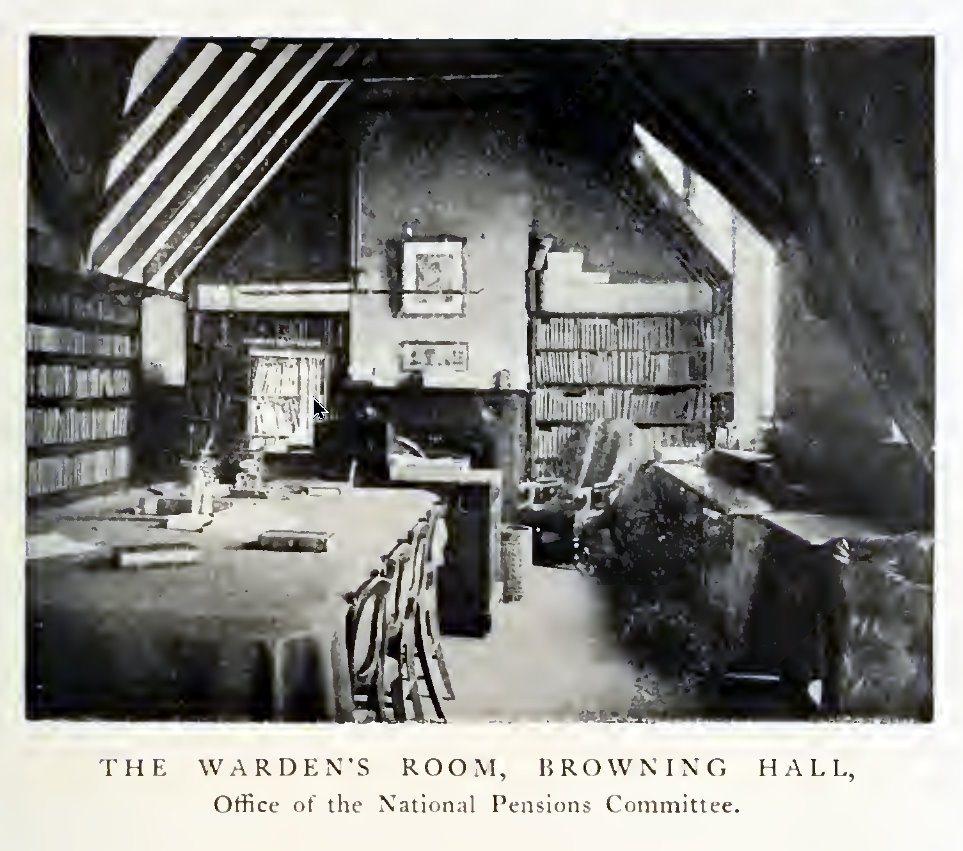

Settlements offered one way forward in the contemporary context – and Stead was impressed by the work of the Barnetts at Toynbee, and Percy Alden and others at the nonconformist Mansfield House in Canning Town (formed in 1890). Frederick Herbert Stead worked to establish a settlement linked to Browning Hall. Inaugurated in November 1895 by an address given in the Hall by Herbert Asquith (British History Online), the settlement was to have a distinctive character and to play an important part in the development of the labour movement in Britain. Stead also became the first warden of the Settlement.

F. Herbert Stead demonstrated considerable abilities as an organizer at the Hall – most famously around the campaign for state pensions for old people (see below). However, he also wrote some important books including an account of the struggle for pensions (Stead 1909), an account of the early years of the work at Browning Hall and Settlement (Browning Hall/Stead 1913), and an exploration of Social Christianity (1924). In 1921, after 26 years as Warden of the settlement, Herbert Stead stepped down. Several major books followed (Stead 1922; 1924; 1927). He died in 1928.

Robert Browning Settlement, Walworth

The Settlement (at what is now 195 Camberwell Road) was in an area of considerable poverty and disadvantage. In June 1902, when opening the new building Charles Booth had the following to say:

For loftiness of ideal, for the successful promotion of the union of Churches in the service of the poor, and for width of practical sympathy with the lives of the people, the Browning Settlement holds the palm among all such institutions. (quoted by Alan Patient undated)

Stead (Browning Hall 1913: 15) echoed strongly Barnett’s belief in the importance of those with education, wealth and social advantage living among the poor and disadvantaged, and joining with them in seeking to make a change (see Barnett 1898). That said, while university people made up the majority of residents, there was an unusually large number who had left education either after elementary or secondary schooling. For example, James Keir Hardie (1856-1915) the first independent labour Member of Parliament (elected to West Ham in 1892) was a resident for a time.

Wood and Ball (1922: 27) comment that Browning Hall was ‘a Social Settlement rather than a University Settlement’. They continue:

Its ideals are more civic than academic. Its aim is to cultivate the friendship of the people of Walworth, to bring sweetness to their lives, and to help them by any and every means that come to hand.

Browning Hall’s entry in the Directory of Settlements also brings out something of the political and religious commitment:

We stand for the Labour Movement in religion. We stand for the endeavour to obtain for Labour not merely more of the good things of life, but most of the best things in life. Come and join us in the service of Him who is the Lord of Labour and the soul of all social reform (quoted by Scotland 2007: 142):

Frances Herbert Stead and his co-workers developed a wide range of clubs and activities – one of which was the Goose Club (which was a savings club for Christmas groceries and which had over 10,000 members by 1908 (Browning Hall 1913: 73). Browning Hall also hosted a significant adult education programme (being the Walworth Centre of the London University Extension Society), organized the provision of country holidays, and made some early efforts in social work training. It opened various facilities including the Browning Tavern – an initially well-used temperance ‘tavern’ that served meals and non-alcoholic drinks; and developed housing provision for older people.

Not unexpectedly given the orientation of Browning Hall, there was considerable concern about the conditions in which local people lived. Unfortunately, the Church of England (through the Ecclesiastical Commissioners) were the ground landlord of some of the worst slums in London – and this became a focus for action by residents – and some clearance work took place (Scotland 2007: 150). The settlement was also involved in the successful campaign for the clearance and redevelopment of the nearby and notorious Tabard Street area (where Charterhouse Mission was also working). Alongside this, the settlement intervened in local elections – making the case for electors to support candidates of ‘good character’. Browning Hall also became a centre for trade union and labour activity – regularly hosting meetings and conferences (see Browning Hall 1913).

Much of the success of the Hall lay with F. H. Stead and his wife Bessie. This is how an early visitor to the settlement described things:

Mr. and Mrs. Stead are peculiarly bright and able people. Few are more cultured, and few represent in themselves a finer type of life. Their settlement is in South London, in the midst of what Mr. Charles Booth has proved to be even more desolate than the East. Before entering this field Mr. Stead had been a pastor in Leicester, and for some years had edited the Independent. From what we know of the workers we should say that Toynbee Hall should be studied as an educational center among the poor; Oxford House for its men’s amusement clubs ; Mansfield House as the one which is doing most to reach and ennoble the laboring men, and to relieve present distress ; and Browning Hall as the one where there is probably the most intelligent and wise study of the many phases of the social problem. (Chicago Commons, October 1896)

One of the key people that Francis Herbert Stead invited to join him was Tom Bryan (who was also a Congregationalist and went on to be the first warden of Fircroft College, Birmingham). Bryan developed various clubs, outdoor meetings and groups. One of his first actions was to establish an adult school which involved short courses and reading circles. Other activities established at Browning Hall included a savings bank, legal aid, summer camps, a ‘Cripples’ Parlour (of which his wife Fanny Bryan was the head) and a Boys Brigade. He became a tireless campaigner around local public health issues (and in recognition of this was elected Mayor of the Borough of Southwark in 1902).

Francis Herbert Stead, Browning Hall and the fight for old age pensions

Frances Herbert Stead had become interested in the question of old age pensions as part of a wider concern with poverty and disadvantage. Other residents at Browning Hall had also become progressively concerned about the plight of older working-class people. In 1898 a committee chaired by Lord Rothschild had argued that there were around one million older people on the breadline – not able to make provision for their basic needs (Scotland 2007: 146). In the same year, the New Zealand government started an innovative pension scheme. Stead invited William Pember Reeves of the New Zealand High Commission to talk about the scheme on several occasions. As a result of the discussions that took place, Stead called a conference at Browning Hall (on December 13, 1898) and invited many key union leaders, some trades council officials and what Macnicol (1998: 145) has described as a ‘motley collection of smaller friendly society officials’. Charles Booth attended and spoke (and this gave the event significance beyond the labour movement).

The Conference at Browning Hall was followed by some regional events – and within a few months the National Committee of Organized Labour for Promoting the Old Age Pensions for All was formed (May 1899) (see Stead 1909). This committee spearheaded the labour movement’s campaign for the next nine years (Macnicol 1998: 146). The work was realized when, in 1908, the Old Age Pension Act received Royal assent. Some months later a member of the Cabinet went to Browning Hall’s Annual General Meeting ‘to extend the government’s thanks to the Settlement for its “splendid educational work in the cause of Old Age Pensions”‘ (Scotland 2007: 147).

Browning Settlement also took an important role in promoting a Bill for National Old Age Homes (based on its own experience of providing ‘homes for old folks’ and that of the Durham and Northumberland Miner’s Homes for the Aged). Unexpectedly, ‘these were made legally possible by a Housing Act on the outbreak of the [First] World War’ (Stead 1924 [Volume 2]: 217).

Conclusion

Frances Herbert Stead is now something of a forgotten figure – although with the celebrations of 100 years of state pensions in Britain in 2008 his name did reappear. Some of his importance (and the significance of the activities of his co-workers at Browning Hall) can be gauged from the following extract of a parody of Browning’s Love among the ruins that appeared in Punch just after the Hall was opened:

Well, a Walworth chap may not quite grasp Sordello,

Poor good fellow!

But the author of Sordello hath the whim

To grasp him,

And for Hall and Settlement to bear his name

He holds fame!

With this Robert Browning Social Settlement

I’m content,

Over poverty, pain, folly, noise and sin,

May they win.

As I say, despite wit, wealth, fame and the rest,

“Love is best“.’*

*Last line of ‘ Love Among the Ruins.” (Punch December 21, 1895 pp. 22-3)

In many respects, Browning Hall was the most politically committed of the university and social settlements (although Mansfield House came close in some ways). They could also claim some major concrete successes over their first twenty years or so. Francis Herbert Stead’s contribution was pivotal. His ability as an organizer, commitment to progressive social action, and ability to demonstrate what social Christianity involved both provided an important example and developed into a movement that made a fundamental difference in the lives of older people in Britain.

References

Barnett, S. A. (1898) ‘University settlements’ in W. Reason (ed.) (1898) University and Social Settlements, London: Methuen.

British History Online. (1955). Nonconformist Chapels in Walworth’, Survey of London: Volume 25, St George’s Fields (The Parishes of St. George the Martyr Southwark and St. Mary Newington), (London, 1955), pp. 101-104. [https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol25/pp101-104. Accessed 30 June 2024].

Browning Hall (Stead, Francis Herbert) (1913) Eighteen Years in the Central City Swarm. London: W. A. Hammond.

Bryan, T. (1912) ‘Education and civic life’ Paper read at the Education Conference of the Cooperative Union in Birmingham, July 20. Reproduced in H. G. Wood and A. J. Ball (1922) Tom Bryan. First warden of Fircroft, London: George Allen and Unwin. Available in the informal education archives: http://www.infed.org/archives/e-texts/bryan_education.htm.

Chicago Commons – A Monthly Record of Social Settlement Life and Work. Volume 1 [http://libsysdigi.library.uiuc.edu/oca/Books2007-07/commonsmonthlyre/commonsmonthlyrev1chic/commonsmonthlyrev1chic_djvu.txt. Accessed August 6, 2008]

Macnicol, John (1998) The Politics of Retirement in Britain 1878-1948, Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Patient, Alan (undated). Robert Browning Settlement. London Remembers [https://www.londonremembers.com/subjects/robert-browning-settlement. Retrieved June 30, 2024].

Scotland, Nigel (2007) Squires in the Slums. Settlements and missions in late Victorian London. London: I B Taurus.

Stead, Francis Herbert (1889) A handbook on Young People’s Guilds, London: Congregational Union of England and Wales.

Stead, Francis Herbert (1892) The English Church of the Future: its polity. A Congregational forecast … together with letters from leaders in the principal denominations of British Christians, etc. London: J. Clark and Co.

Stead, Francis Herbert (1909) How Old Age Pensions Began to Be. London: Methuen and Co. Available online: http://www.archive.org/stream/howoldagepension00stea. [Accessed September 23, 2008].

Stead, Francis Herbert (1909). To Abolish War. Letchworth: Garden City Press. Available online from the Internet Archive.

Stead, Francis Herbert (1917) No more War! “Truth embodied in a tale.”. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co.

Stead, Francis Herbert (1922) The Unseen Leadership. A word of personal witness. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Stead, Francis Herbert (1924) The Story of Social Christianity. 2 vols. London: James Clark and Co. Available online: https://archive.org/details/storyofsocialchr0000stea.

Stead, Francis Herbert (1927) The Deed and the Doom of Jesus. London: J. Clark and Co.

Wood, H. G. and Ball, A. J. (1922) Tom Bryan. First warden of Fircroft, London: George Allen and Unwin.

Photograph: Robert Browning Settlement sign 195 Walworth Road, Southwark – LondonRemembers.com | The pictures of Browning Hall and the warden’s room are included in Stead (1909) and are published here as they are believed to be out of copyright.

How to cite this piece: Smith, Mark K (2008, 2024) ‘Francis Herbert Stead, Browning Hall and the fight for old age pensions’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [www.infed.org/thinkers/herbert_stead_browning_hall_pensions.htm].

© Mark K Smith 2008, 2024