Leonard Barnett and the church youth club. Leonard P. Barnett was a key figure in the development of youth work within the Methodist Church. He also wrote two classic texts on youth clubs that provide workers with a coherent and informed basis for their work fostering learning, fellowship and the more abundant life.

Leonard Barnett and the church youth club. Leonard P. Barnett was a key figure in the development of youth work within the Methodist Church. He also wrote two classic texts on youth clubs that provide workers with a coherent and informed basis for their work fostering learning, fellowship and the more abundant life.

contents: introduction · leonard barnett – life and works · the church youth club · education and evangelism · fellowship, friendship and association · club and church · conclusion · further reading and references · links · how to cite this article

The Rev Dr Leonard Palin Barnett BD (Lond), Hon LDH (1919-2001) was well known and respected as a Methodist minister, preacher and writer. He was also a frequent contributor to BBC radio’s Thought for the Day. However, it was his time spent as National Secretary of the Methodist Association of Youth Clubs (1949-1958) – and his contribution to the the thinking and practice of work in church youth clubs that is our focus here. His books The Church Youth Club (1951) and Adventure with Youth (1953; 1962) were important and pioneering works. Leonard Barnett looked to the power of fellowship and the educative nature of club life – but set these in a rounded Christian understanding. ‘It is only with that prior knowledge, plus our own deep spiritual convictions about God and man, that we can hope to see practical matters of club life and organization in their proper light. We can only see where we should be going, in club, when we see where they, the boys and girls, are in fact going. He believed that the task of Church club leaders was both to educate and evangelize.

Leonard Barnett – life and works

Leonard Barnett was born in 1919 in Crewe. His father had worked on the railways and was a local Methodist preacher; his mother was a teacher who encouraged her sons to take school seriously (Greet 2001). Aged 17 years, Leonard left and entered the Civil Service in London – working in the Post Office. According to Tom Styche (2001) he worshipped at Kingsway Hall and was greatly inspired by the preaching and guidance of Donald Soper.

His stirring preaching of the Gospel of the kingdom, his vision of a better world, his advocacy of the cause of peace fired the Heart and quickened the mind of this young man. Early on, he grasped the fact that shaped his life and ministry down the years. That the outrageously radical element in the teaching of Jesus is the news that the God whom we worship is a non-violent God who calls his servants to the way of non-violence. (Greet 2001)

Barnett offered himself, and was accepted, as a candidate for the ministry. In 1939 Leonard Barnett went to Hartley Victoria College to train. He spent his probationary period at Holyhead and then moved to the Nantwich Circuit. There he met and married May – who was to be a key influence in his life. He had two sons: Andrew (born in 1949) and Richard.

At the end of the Second World War Leonard Barnett was sent to Guernsey to help re-establish youth work on the island. One his innovations was to start a youth hostel in a disused church. In 1949 Leonard Barnett was appointed National Secretary of the Methodist Association of Youth Clubs (MAYC). The Methodist Youth Department had been established in 1943 (bringing together the existing Sunday School and Guild Departments) and under the guidance of Rev. Douglas A. Griffiths MAYC came into existence in 1945 (Hubery 1963: 80). When Leonard Barnett joined MAYC it was working from buildings in Ludgate Circus. Under his secretaryship special attention was given to training and laying a proper foundation for youth club work within the Methodist Church. He wrote two classic texts: The Church Youth Club (1951) which reviewed recent developments and provided a rationale and theoretical base for church youth club work; and Adventure with Youth (1953; 1962) – a handbook for church club leaders. As Hubery (1963: 80) comments, it became the standard work on youth service within the Church.

After nine years at MAYC Leonard Barnett moved to Doncaster Trinity Place as Superintendent Minister, and then in 1962 went to Epsom. He was also to serve Methodist churches in Finchley, Bromley, Ewell and Cheam. He retired in 1983, but remained very active – being a regular preacher around Methodist circuits and involved in his own church in Epsom. He was also involved in the Back Pain Association, the University of the Third Age (in the Sociology Group), and a member of the Epsom Literary Society (Styche 2001).

Leonard Barnett spent his final days at Collumpton House. He died on June 26, 2001. Kenneth Greet (2001) reported:

On one of my last visits, Len was sitting by a table. On the table, there was a notebook and pen. But there was no writing on the page. The pen that had sped so swiftly was still and the voice that had preached so eloquently was silent. Len sat there waiting. Waiting for what?

For the moment when death would be swallowed up in victory and when, wonderfully when all his powers would find sweet employ in that eternal world of joy.

The church youth club

‘In essence’, Leonard Barnett (1951: 27) wrote, ‘a church youth club is a community of young people engaged upon the task of Christian education’. He saw that there was ‘a natural desire’, on the part of young people, to associate with others passing through the same experiences as themselves.

There is an immediate community of interest in the solid fact that they are growing up together. And the club is a place where not only can young people find a common bond of sympathy, but can together discover, in company with wise leaders, the secrets of harmonious self-adjustment. (Barnett 1951: 30)

His emphasis on the youth club as an educative community, and his concern with the associational needs of young people owed a great deal to the work of Josephine Macalister Brew (indeed Brew wrote the foreword to The Church Youth Club) and Marjorie Reeves. However, what Leonard Barnett was able to add was a distinctly Christian appreciation of the possibilities of club life.

A club… must be seen as an instrument which can aid and abet to a large degree the unfolding of the more abundant life by those who are members of it. It is a community which seeks to help forward the process of education for life by its consistent care for body, mind and spirit. And the differentiae of the church youth club derive from a basic conviction that the Christian faith alone and in its fullness can prove the ultimate integrating factor, both for the individual and for the community. It bids us exercise an over-all care for the well-being of the whole person, body and mind no less and no more than spirit, believing that they together form an inviolate trinity. (Barnett 1951: 34)

Our job is to provide such opportunities for development of body, mind and spirit, as will enable the boys and girls in our club to enter upon fullness of life as the sons and daughters of the living God. (Barnett 1962: 3)

When Leonard Barnett wrote The Church Youth Club (1951) there had been an extra-ordinary expansion of the membership of youth clubs (especially within the Methodist Church) (see Jeffs 1979; Smith 1988). Brian Reed (1950: 95), for example, reported in his survey of youth work in Birmingham that a great majority of the clubs identified had only come into existence recently. Leonard J. Barnes (1945) had also earlier identified a very significant growth in the proportion of young people attending youth clubs and youth provision in his study of Nottinghamshire. Leonard Barnett saw this as a great opportunity – many of the young people attracted to did not come from Church backgrounds and were groping after ‘a coherent view of life and their part in it’ (Barnett 1951: 32). Here, the club, as an educative community, had a vital role to play. It allowed for the free exchange of ideas, doubts and beliefs – and ‘in the communication of a pattern of thought and conviction occasioned by the very nature of the group of which the adolescent is a part’ (ibid.: 33).

Education and evangelism

Like later writers concerned with informal education (e.g. Jeffs and Smith 1990) Leonard Barnett placed fostering the good life at the centre of his conception of education. His concern for living life well (informed by his Christian convictions) and of the need to help everyone, ‘to play the highest and best part possible for him in the life of the society he belongs to, at each stage of growth and development’ (Barnett 1962: 5) provided the framework for educational effort.

Let us see this business of education in a practical setting. Think for a moment of the friends and acquaintances you regularly mix with. How many of them could you honestly say were characterized by an infectious zest for life, an obvious capacity for vigorous enjoyment of all it offers day by day? From how many of them do you confidently expect a considered opinion on any matter of general moment? How many strike you as balanced people holding reasoned (albeit simple) convictions? How many are typically stable, reliable people, not given to touchiness, mulishness, lethargic indifference, or other common features of an ill-balanced emotional life? How many practice consistently high personal standards and values? What proportion of them find regular enjoyment in reading books (other than light novels), listening to or helping to make decent music or stimulating conversation? How many of them are not only good at their work, but good also at getting on with their workmates and getting the best out of them? How many of them, would you say, habitually display the fruits of what can only be termed a philosophy of life? Do many betray abundant signs of a practical faith in themselves, their fellow-men, or God?

These are a few facets of the good life; the life of the educated man. A true education means the provision of such conditions as help human life to achieve abilities like these.

Leonard Barnett was at some pains not to set evangelism and education against each other. The task of workers in clubs, as we have seen, was to help young people ‘to grow up so as to enjoy the more abundant life…, to enter upon the fullness of life as the sons and daughters of the living God’ (Barnett 1962: 3). He endorsed the broader youth work concern for the development of mind, body and spirit – but was quite clear about how this was to be interpreted.

[W]e are bound in humility but conviction, to say dearly that for us, to grow to the full stature of men and women involves not only as healthy a body, as alert and informed a mind as possible, but also—supremely essential, and giving sense to both these—a personal relationship with Jesus Christ as Lord and Saviour. “Spiritual development” must be interpreted in those terms. The Christian Gospel is at once universal and authoritative. And “by their fruits, ye shall know them” must be taken here as everywhere else, as the acid test by which such Christian convictions must be judged.

That is to say, as Church club leaders we are educators, and evangelists… The youth club job is to educate; and to evangelize, in a Christian sense. And though we must part these two foundation principles in order to see their respective functions, it is of first importance to remember always that in practice they interweave inextricably throughout the whole of club life. (Barnett 1962: 4)

In contrast to to contemporary writers like L. J. Barnes he did not see character-building (inculcation) and the growing of personality (facilitation) as opposites. ‘In the business of Christian character-building’, Barnett (1951: 42) comments, ‘we are at no point called upon either to flee from reason, to disallow its claims, or to set it in opposition to the very process we are endeavouring to facilitate. And we may attempt to communicate the truth about life – an essentially religious truth – to club members, without doing despite to their personalities’.

Fellowship, friendship and association

One of the striking things about reading writers like Leonard Barnett today is the extent to which we have, today, been conditioned by professionalized and bureaucratized appreciations of what it is to be an educator and worker with young people. Within the professionalized view of the world there has been a shift from a concern with fostering community and association to much more privatized and individualized approach (much as C. Wright Mills argued would happen at the time Barnett was initially writing). There is, today, a much stronger focus on the troubles of the individual in youth work practice than with public issues. A dangerous element of this is the way in which public issues (such as the inability of schools to accommodate the different cultures and experiences of school students) are reformed as private troubles (truancy, for example, may well be presented as a result of poor student adjustment to schools). Reading Leonard Barnett we enter something of a different world – one in which the problems of the individual are seen as being related to the experiences of others, and to God. It is also a place where workers might be expected to have vocation or calling, and where their work is viewed as contributing to the health of a movement. These elements are, of course, familiar to the many workers operating within and around churches – but Leonard Barnett’s emphasis upon fellowship, friendship and association may well still be a little strange to ‘modern’ ears.

Let us look first at fellowship.

To my mind, this term “fellowship”, often so inadequately and lightly used by people within and outside the Churches, is the most vital word we need to have a full awareness of. It is steeped in New Testament values. In apostolic times, the koinonia or fellowship of the Church was its very life and essence. It still must be, if the Church is to minister truly to the young people within thousands of church clubs. Then, it carried no narrowly devotional connotation. It was not bound up with “meetings,” but with “meeting” at every stage and level of experience. It was not concerned with the culture of the soul only, but with a care for the whole person. Its hall-mark was the agape, the love or charity, of the New Testament. It is that rich and all embracing content which once more we must put into the word making it relevant to life in every aspect. It represented the fusion of the outgoing Christian love of every believer, issuing in a community experience which was intensely and essentially trustful, reverential always as regards the rights of the individual, and responsible to God and all mankind. (Barnett 1962: 75)

Fellowship is something more or different to friendship. For Len Barnett (like many others involved in informal education and lifelong learning at that time) it was an extension or expression of God’s Kingdom on earth. It involves encounter – what Martin Buber describes as a meeting between two or people who are fully present to each other. In other words, they connect as whole people – and this necessarily involved God. Such fellowship, as Richard Tawney had earlier seen, was not just a matter of feelings, ‘but as a matter of right relationships‘ which are institutionally based‘ (Terrill 1973: 199). In other words, fellowship entails the presence of God, and is both a quality of individual relationships, and the organizations and systems of which people are a part.

Like many other club workers at the time, Leonard Barnett was strongly committed to association. The process of joining together in fellowship to undertake some task – and the learning and good that flows from playing one’s part in a group or association was of great significance to him. Part of the essential nature of the club lay, for Barnett, in its character as a voluntary community of friends. However, another essential feature was ‘that of an adolescent community encouraged to take into its own hands as much of the practical organization and government as the members themselves are capable of assuming’ (Barnett 1962: 78). He was also acutely aware of the scope and nature of the task.

Self-government is not only a matter of Members’ Committees. It is a matter of the common weal, of the true concept of democracy as an order of society in which everyone finds a significant place. And this must be true of your club. “A real job for every member” is the perfectly practicable ideal for the self-respecting club. It should not be beyond the wit of any leader to discover the way to employ, in some significant fashion, every single member of the club. And it is hardly necessary to add that this sharing of responsibility, and the practical organization it involves, is likely to prove one of the most severe practical tests not only of the members’ but also the leader’s power to persevere.

All this brings back to friendship – the ‘mutual affection divested of sentimentality’ that is ‘the cornerstone of fellowship, adding both strength and grace to the final structure of personality’ (Barnett 1962: 77). Today it can be argued that we have a very thin appreciation of friendship. For example, Bellah et. al. (1996: 115), drawing upon Aristotle, suggest that the traditional idea of friendship has three components: ‘Friends must enjoy each other’s company, they must be useful to one another, and they must share a common commitment to the good’. In contemporary western societies, it is sometimes suggested, we tend to define friendship in terms of the first of these elements. Len Barnett’s conception of friendship involved all three elements – but these were permeated and infused by Christian faith.

Like other club workers at the time (see, for example, Basil Henriques) Barnett looked to the club leader as friend with particular ‘personal’ moral authority:

The leader has no authority save that of “personal” moral authority. He stands in a unique relationship different from that of teacher-pupil or parent-child. And because he has not had authority over his members during their recent childhood, he will be in a position to take helpful advantage of the teenage tendency to confide in and take particular note of the opinions of such people. He stands in the relation of a friend, separated from his members by the simple, scaleable barriers of age and experience. The education that the club provides must therefore be informal, and interesting as possible. (Barnett 1962: 11)

Church club leaders had to enjoy the company of the members; be useful to them (and allow members to be of use); and share a common commitment to trying to live life well within the Christian faith. It is this that makes them friends, rather than just friendly, with the young people they work with.

Club and church

Leonard Barnett had a particular appreciation of the role that youth clubs play in the life of local churches.

The church youth club must be seen as an out-working of the faith and practice of the local community of Christians. It is an expression of the Church’s awareness of its responsibility to care for all… [Y]et in some quarters, one still hears it lamented that all and sundry young people come into this church club and that…. [T]he church youth club being what it is – a means of Christian education and evangelism – then the only criticism on this issues is that which might be launched against the ‘closed’ church club, which seeks as members only those who already have some association with the church in question. (Barnett 1951: 48)

He continues:

the more searching test of the true missionary spirit of many a Christian community has been the readiness or otherwise of its members to recognize that the unchurched youngsters who have crowded boisterously into its premises are part of the very constituency it was called into being to serve, and the neglect of which the church loses its very raison d’etre. (ibid.: 49)

The church club exists, Barnett argued, to provide ‘informal but adequate Christian education – in short to produce young Christians’ (1951: 50). As we might expect from the above emphasis on fellowship, he believed that personal encounter should lead to common enterprise (1951: 52).

A most vital part of the Christian’s creed is his belief that just as he has entered into an experience of God’s Fatherhood, so must that experience lead to practical action in his attempts to build and strengthen a family community where all men shall truly be at home together. The present expression of that community is the Church.

Leonard Barnett was well aware that the close association of a club with a church could sometimes prove a liability – with a lack of sympathy and co-operation on the part of adult church members and officers (1962: 184). He also appreciated that there might well be rather unrealistic expectations placed upon club leaders by members of local congregations. However, her believed that these things were to be approached in the spirit of fellowship – and that a key part of the worker’s job was to try to build bridges and to work so that diverse groups and individuals could encounter each other in a spirit of exploration and service.

Conclusion

The mainsprings of the leader’s every action in his club are his living faith, his personal devotion to his Church, and his genuine love for all his members. If these springs are not taut and coiled, if they are weak and flaccid, then he can never be a truly fit leader. Neither will added strength of one avail if another has lost its resilience. It is a case of all or nothing. (Barnett 1951: 143)

Church club leadership was, for Leonard Barnett, a Christian vocation – and ‘must be consistently regarded as such’ (ibid.: 142). It was something that took considerable time

[C]lub work is necessarily a slow process. No one can offer youth pre-fabricated friendship. To build that intensely personal relationship is essential a brick-by-brick operation. Club work is not a ten-day mission to youth. It is much more like a five-year plan. If a solid structure is to be built, then there is much debris of mutual ignorance and misunderstanding to clear away first, and ground to be levelled, before the materials of construction can be placed in position. To rush the job is to jeopardize the whole project. (Barnett 1951: 22)

Leonard Barnett’s vision was to inspire many workers and his practical guidance helped many clubs to flourish. His work in this area was distinguished by an attention to theoretical and theological issues that was grounded in the experience of the everyday. His was a rare gift – and he still has much to say to present day workers. We would do well to look closely at the power and possibilities of club life; to examine informal Christian education; and to explore the the experience of fellowship.

Further reading and references

Barnett, Leonard P. (1951) The Church Youth Club, London: Methodist Youth Department. 190 pages. A path-breaking account of the church youth club that connects theory and empirical research with a great deal of practical wisdom about practice. As well as including useful material on the development of Methodist youth work there is discussion of the function of the club, relationships between churches and clubs, and the qualities of church club leadership.

Barnett, Leonard P. (1953; 1962) Adventure with Youth : a handbook for church club leaders, London: Methodist Youth Department. A popular ‘principles and practices’ handbook for church club workers. It provides a clear and properly theorized framework for the work – and lots of practical guidance.

References

Barnes, L. J. (1945) Youth Service in an English County, London, King George’s Jubilee Trust.

Barnes, L. J. (1948) The Outlook for Youth Work, London: King George’s Jubilee Trust.

Barnett, Leonard P. (1955) What’s the use of youth clubs : M.A.Y.C. clubs suggest an answer / a survey, London: Methodist Youth Department

Barnett, Leonard P. (1966) Here is Methodism : for church membership training groups and other interested people, London: Epworth.

Barnett, Leonard P. (1966) Getting it over : a guide book for the Christian advocate, London: Denholm House.

Barnett, Leonard P. (1980) What is Methodism? London: Epworth Press.

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A. and Tipton, S. M. (1985; 1996) Habits of the Heart. Individualism and commitment in American life 2e, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Brew, J. Macalister (1943) In The Service of Youth. A practical manual of work among adolescents, London: Faber.

Brew, J. Macalister (1946) Informal Education. Adventures and reflections, London: Faber.

Greet, K. (2001) ‘Leonard Barnett. A tribute’, Epsom Methodist Church, http://www.emc.org.uk/leader/leader index.htm

Jeffs, T. (1979) Young People and the Youth Service. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Jeffs, T. & Smith, M. (eds.) (1990) Using Informal Education. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. (Full text is in the archives)

Ministry of Education (1945) The Purpose and Content of the Youth Service. A report of the Youth Advisory Council appointed by the Minister of Education in 1943. London: HMSO.

Reed, B. (1950) Eighty Thousand Adolescents. A study of young people in the City of Birmingham by the staff and students of Westhill Training College, London: George Allen and Unwin.

Reeves, M. (1945) Growing Up in Modern Society, London:

Smith, M. (1988) Developing Youth Work. Informal education, mutual aid and popular practice. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. (Full text in the archives)

Styche, T. (2001) ‘Rev Dr Leonard P Barnett’, Epsom Methodist Church, http://www.emc.org.uk/leader/leader index.htm

Links

Leonard Barnett – club and church (the informal education archives)

Leonard Barnett – why youth clubs? (the informal education archives)

Leonard Barnett – responsible people (fellowship and self-government in church youth clubs) (the informal education archives)

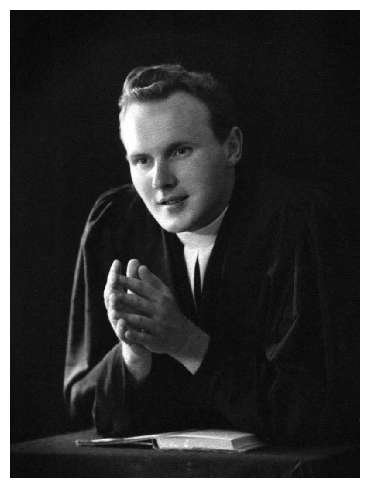

Acknowledgement: Picture: Leonard Barnett in 1947 (with kind permission of his family).

To cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2002). ‘Leonard Barnett and the church youth club’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [ https://infed.org/dir/leonard-barnett-and-the-church-youth-club/. Retrieved: insert date]

© Mark K. Smith 2002

Leonard Barnett and the church youth club. Leonard P. Barnett was a key figure in the development of youth work within the Methodist Church. He also wrote two classic texts on youth clubs that provide workers with a coherent and informed basis for their work fostering learning, fellowship and the more abundant life.

Leonard Barnett and the church youth club. Leonard P. Barnett was a key figure in the development of youth work within the Methodist Church. He also wrote two classic texts on youth clubs that provide workers with a coherent and informed basis for their work fostering learning, fellowship and the more abundant life.