Murray Bookchin: social anarchism, ecology and education. Murray Bookchin made a significant contribution to the development of thinking around ecology, anarchism and later communalism. As a result he helped to shape the anti-globalization movement – and has continuing relevance for informal educators and those seeking to foster more convivial forms of learning. Mike Wood explores Bookchin’s contribution.

contents: introduction · life and contribution · social anarchism · murray bookchin on education · conclusion · further reading and references · how to cite this piece · about the writer

Murray Bookchin (1921-2006) was one of the most insightful and controversial anarchist thinkers of the mid-to late twentieth century. His ideas on localized, self-governed communities seem particularly insightful today, as the strains of globalization and resource depletion has made “thinking local” a viable plan for future societal sustainability. Bookchin’s ideas have particular relevance for informal adult education, ideas he used in his own history as a teacher.

Life and contribution

Bookchin was born in New York City to the Russian Jewish immigrants. Both parents were Marxists, and he was, thus, exposed to left ideology from a young age. He worked in factories (including General Motors) when older and put rhetoric into action, becoming an organizer for the Congress of Industrial Organizations in the early 1930s. By the end of that decade, Stalinist purges and show trials lead him briefly toward Trotskyite ideals, eventually breaking with Communism altogether. Seeking a less centralized, oppressive forum, he founded the Libertarian League in 1950s New York. Continuing to work a series of manual labour jobs, he began writing down his own theories and also began teaching, first at the Free University in Manhattan in the late 1960s. This lead to a tenured position at Ramapo State College in Mahwah, NJ. Most significantly, in 1971 he co-founded, the Institute for Social Ecology at Goddard College in Vermont, an institution with a long history of anarchist ideals and informal learning. Murray Bookchin taught there until 2004. His collection of essays – Post-Scarcity Anarchism (published in 1971 and including the seminal piece ‘Listen Marxist!’) – not only helped to redefine anarchist thinking but also laid the foundation for anarchism’s influence in the later anti-capitalist movement. In the 1970s he was involved with the Clamshell Alliance, an anti-nuclear group which pioneered tactics of non-violent direct action (Small 2006).

One can argue that Murray Bookchin played a significant part in stimulating the environmental movement, since his 1962 book Our Synthetic Environment, published as Lewis Herber, came out shortly before Rachel Carson’s more celebrated Silent Spring. As Janet Biehl (c2007) has commented it was significant because it was written for a general readership and highlighted the environmental threat posed in a number of areas. He discussed pesticides, food additives, and X-radiation as sources of human illness, including cancer (op. cit.). Other books of his that influenced a generation of radicals to consider both the community and the planet include The Ecology of Freedom (Bookchin 1982), The Rise of Urbanization and the Decline of Citizenship (republished as From Urbanization to Cities) (Bookchin 1995b), and The Third Revolution (Bookchin 1996).He also wrote many essays that challenged Marxist presumptions and the danger of radical individualism at the expense of the larger community.

A pioneer in the ecology and conservation movements, Murray Bookchin was also a libertarian socialist whose ideas on the social role of anarchism put him at violent (at least verbally) odds with a new generation of anti-capitalists who focused more on personal rebellion than social action. To Bookchin, this was a retreat into a bourgeois self-absorption that absolved anarchists from responsibility to enact change, thereby betraying the basic principles set down in the nineteenth century by Bakunin, Kropotkin and others.

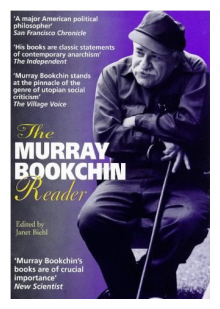

A great believer in Goya’s statement that “Imagination without reason produces monsters,” Murray Bookchin increasingly became opposed to some movements that he initially inspired. The Deep Ecology philosophy seemed to him to be a retreat into mythology, rather than a force for real action and change. He believed the environmental movement was drifting into a self-absorbed, self satisfied longing for oneness with nature, a return to an intuitive relationship with the land, a myth that, like all myths to Bookchin, was based on fear of reality and self-centeredness. By 2000 he was framing his ideas within communalism rather than anarchism (Bookchin 2007). During this period he worked with his partner of some twenty years – Janet Biehl – both to produce a reader, and an overview of his thinking (The Politics of Social Ecology) (Biehl and Bookchin 1998).

Murray Bookchin died at his home of heart failure in July 2006 in Burlington, Vermont. He was 85. Bookchin was survived by his partner Janet Biehl, his former wife Bea and his son and daughter.

Social anarchism

His main ideological battle played out in the distinction between lifestyle anarchism and social anarchism, the latter of which he championed. In lifestyle anarchism, promoted by the like of Hakim Bey and the magazine Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed, the focus is on the self. One can, no matter the circumstances, create a liberate space for oneself—an “autonomous zone,” at any time, within which one can be free of the State and creatively independent. To Murray Bookchin, that was a recipe for self-absorption:

Thus is social nature essentially dissolved into biological nature; innovative humanity, into adaptive animality; temporality, into precivilizatory eternality; history, into an archaic cyclicity. Lifestyle anarchism, by assailing organization, programmatic commitment, and serious social analysis, apes the worst aspects of Situationist aestheticism without adhering to the project of building a movement. As the detritus of the 1960s, it wanders aimlessly within the bounds of the ego and makes a virtue of bohemian incoherence. (Bookchin 1995a)

To Murray Bookchin, this detachment achieves ‘not autonomy but the heteronymous ‘selfhood’ of petty-bourgeois enterprise’. He used the traditional Vermont Town Meeting as an example of sustainable, local, communal anarchy, in which each has a voice in the affairs of the whole while still able to stand as an individual. Bookchin’s ideas, as applied to informal education, zones of autonomy can be created from within which opportunities to affect the larger community are possible. He stressed the need for a ‘new politics—grassroots, face-to-face, and authentically popular in character’ that was ultimately ‘structured around towns, neighbourhoods, cities, citizens’ assemblies, freely confederated into local, regional and ultimately, continental networks’.

Murray Bookchin on education

In an informal educational setting Murray Bookchin’s ideas can be seen and expressed in a variety of ways:

- Seeing the teacher as partner in learning, not as an ultimate authority.

- Individualized learning plans and paces, in which the learner gains knowledge relevant to them and their needs in order to advance.

- Recognition of the whole person—the need for breaks, need for quiet space, need to leave early, recognition that learners have complex lives beyond the classroom and may benefit from being in class for reasons beyond learning.

- Respecting students as adults while maintaining order—to discipline without demeaning them.

- The celebration of small victories.

- Setting realistic goals—an honest environment that is compassionate and respectful, but clear about expectations.

- Recognition that learner may be better served elsewhere.

- Through individualized, the needs of the group—for safety, respect, attention, instruction—is paramount; ensuring this can mean anything from asking learners to leave program to peer tutoring, small group exercises, parties, etc.

- The recognition and reinforcement of the fact that as the learner improves, new knowledge and ideas will be brought back to the family and to the community, creating opportunities for empowerment.

Conclusion

Murray Bookchin’s work as activist, philosopher, teacher and community organizer is still relevant today. Bookchin’s insistence on building local, communal awareness through individual empowerment and collective sharing ring true today, in a world where the retraining of adults in new skills and the need to think locally are keys to economic recovery in the poorest neighborhoods.

Further reading and references

Bookchin, Murray (1971) Post-Scarcity Anarchism. San Francisco: Ramparts. Also published 1974 by Wildwood House, London. 288 pages. Influential collection of essays that sought to integrate ecological ideas with a libertarian theory of society. Includes ‘Listen Marxist’, ‘Post-Scarcity Anarchism’ and ‘Ecology and revolutionary thought’.

Bookchin, Murray (1971) Post-Scarcity Anarchism. San Francisco: Ramparts. Also published 1974 by Wildwood House, London. 288 pages. Influential collection of essays that sought to integrate ecological ideas with a libertarian theory of society. Includes ‘Listen Marxist’, ‘Post-Scarcity Anarchism’ and ‘Ecology and revolutionary thought’.

Bookchin, Murray (1982) The Ecology of Freedom: The emergence and dissolution of hierarchy. Palo Alto, Calif: Cheshire Books.

Bookchin, Murray, and Janet Biehl (1997) The Murray Bookchin Reader. London: Cassell. Excellent starting point for an exploration of Bookchin’s thinking. Includes an introduction by Murray Bookchin and by Janet Biehl.

Murray Bookchin Archive at Anarchy Archives – As well as a short biography by Janet Biehl, the archive includes various pieces by him, and Janet Biehl’s introduction to the Reader.

Bibliography

Biehl, Janet (c2007). ‘A Short Biography of Murray Bookchin’, Anarchy Archives. [http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/bookchin/bio1.html. Accessed January 23, 2010].

Biehl, Janet and Murray Bookchin (1998). The politics of social ecology: Libertarian municipalism. Montreal: Black Rose Books.

Bookchin, Murray (writing as Lewis Herbert) (1962). Our Synthetic Environment.

Bookchin, Murray (1971). Post-Scarcity Anarchism. San Francisco: Ramparts. Also published 1974 by Wildwood House, London.

Bookchin, Murray (1982). The Ecology of Freedom: The emergence and dissolution of hierarchy. Palo Alto, Calif: Cheshire Books.

Bookchin, Murray (1983). ‘Spectacle to Empowerment: Grass Roots Democracy and the Peace Process’ in Burlington Peace Coalition. The Vermont peace reader 1983: Vermont strategies, non-violent civil disobedience, church activism, the European peace movement, poetry, fiction, and more. Burlington, Vt: The Coalition.

Bookchin, Murray (1986). The Limits of the City 2e. Montreal: Black Rose Books. Originally published in 1973.

Bookchin, Murray (1986). “Municipalization: Community Ownership of the Economy” (Green Perspective, February 1986)

Bookchin, Murray (1995a). Social anarchism or lifestyle anarchism: The unbridgeable chasm. Edinburgh, Scotland: AK Press.

Bookchin, Murray (1995b). From urbanization to cities: Toward a new politics of citizenship. London: Cassell.

Bookchin, Murray (1996). The third revolution: Popular movements in the revolutionary era. London: Cassell.

Bookchin, Murray (2007). Social ecology and communalism. Edinburgh: AK Press.

Bookchin, Murray, and Janet Biehl (1997). The Murray Bookchin reader. London: Cassell.

Herber, Lewis (1962). Our synthetic environment. New York: Knopf.

Small, M. (2006). ‘Murray Bookchin – obituary’, The Guardian, August 8, 2006. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2006/aug/08/guardianobituaries.usa. Accessed January 23, 2010].

Sucher, J., & Fischler, S. (1981). Anarchism in America? United States: Pacific Street Film Projects, Inc. [production company].

Acknowledgements: The picture: Bookchin’s bookshelf is by Phillip Chee. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 Generic licence – http://www.flickr.com/photos/pchee/187086897/. Additional information gathered from Wikipedia

How to cite this piece: Wood, Mike (2010). ‘Murray Bookchin: Social anarchism, ecology and education’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/murray-bookchin-social-anarchism-ecology-education/. Retrieved: Insert date].