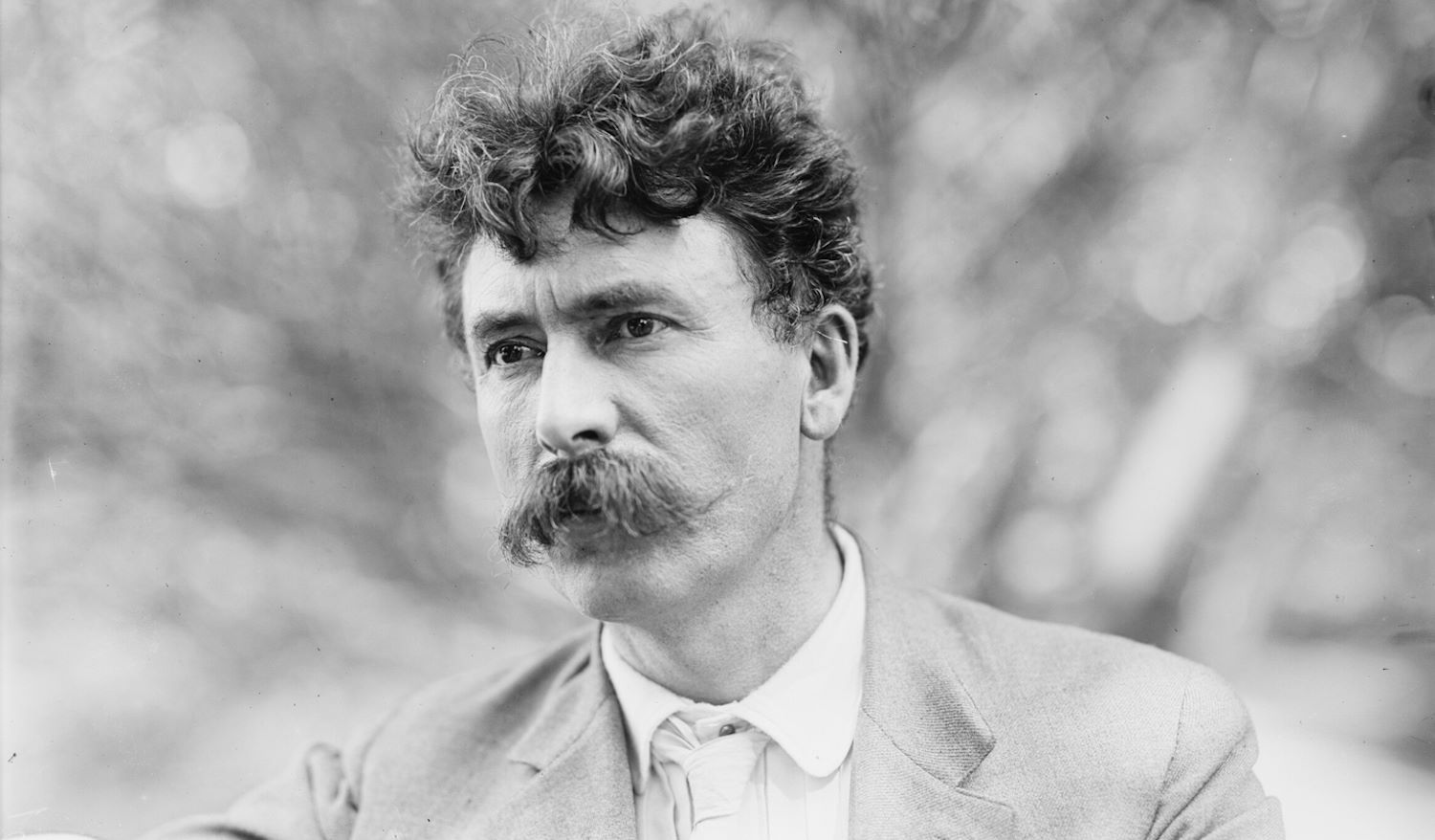

Ernest Thompson Seton and woodcraft. Known as a writer of animal stories, and the Chief Scout of the Boys Scouts of America, Ernest Thompson Seton was a champion of the spirit of woodcraft.

Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946) grew up in Toronto (although he was born in South Shields, County Durham, England). He was the son of a ship builder who, having lost a significant amount of money left for Canada to try farming. Unsuccessful at that too, his father gained employment as an accountant. Macleod (1983: 6) records that much of Ernest Thompson Seton ‘s imaginative life between the ages of ten and fifteen was centred in the wooded ravines at the edge of town, ‘where he built a little cabin and spent long hours in nature study and Indian fantasy’. His father was overbearing and emotionally distant – and he tried to guide Seton away from his love of nature into more conventional career paths. Seton went through puberty late, and ‘suffered the social handicaps that slow development entails. [He] fled outdoors for solace’ (ibid.: 7).

He displayed a considerable talent for painting and illustration and gained a scholarship for the Royal Academy of Art in London. However, he was unable to complete the scholarship (in part through bad health). His daughter records that his first visit to the United States was in December 1883. Ernest Thompson Seton went to New York where met with many naturalists, ornithologists and writers. From then until the late 1880’s he split his time between Carberry, Toronto and New York – becoming an established wildlife artist (Seton-Barber undated). In 1902 he wrote the first of a series of articles that began the Woodcraft movement (published in the Ladies Home Journal). He had invited a group of boys to camp at his estate in Connecticut in the same year and had experimented with woodcraft and Indian-style camping. However, he began developing his ideas around woodcraft from the 1880os on.

In 1910 Ernest Thompson Seton became chairman of the founding committee of Boy Scouts of America. As part of his involvement he wrote the first handbook (it incorporated some material from Robert Baden-Powell’s Scouting for Boys). He served as Chief Scout from 1910 until 1915. As his daughter put it, ‘Seton did not like the military aspects of Scouting, and Scouting did not like the Native American emphasis of Seton. With WW I, the militarists won, and Seton resigned from Scouting’. He revived Woodcraft in 1915 as a coeducational organization – the Woodcraft League of America – as a co-educational program open to children between ages “4 and 94”.

Exhibit 1: The nine leading principles of woodcraft

Ernest Thompson Seton first set out what he saw as the ‘cardinal principles’ of woodcraft in 1910. This version was in the 1927 edition of The Birch Bark Roll.

(1) This movement is essentially for recreation.

(2) Camp-life. Camping is the simple life reduced to actual practice, as well as the culmination of the outdoor life.

(3) Self-government with Adult Guidance. Control from without is a poor thing when you can get control from within. As far as possible, then, we make these camps self-governing. Each full member has a vote in affairs.

(4) The Magic of the Campfire. What is a camp without a campfire? — no camp at all, but a chilly place in a landscape, where some people happen to have some things… The campfire… is the focal center of all primitive brotherhood. We shall not fail to use its magic powers.

(5) Woodcraft Pursuits. Realizing that manhood, not scholarship, is the first aim of education, we have sought out those pursuits which develop the finest character, the finest physique, and which may be followed out of doors, which in a word, make for manhood.

(6) Honors by Standards. The competitive principle is responsible for much that is evil. We see it rampant in our colleges to-day, where every effort is made to discover and develop a champion, while the great body of students is neglected, That is, the ones who are in need of physical development do not get it, and hose who do not need it are over-developed. The result is much unsoundness of many kinds. A great deal of this would be avoided if we strove to bring all the individuals up to a certain standard. In our non-competitive tests the enemies are not “the other fellows,” but time and space, the forces of Nature, We try not to down the others, but to raise ourselves. Although application of this principle would end many of the evils now demoralizing college athletics. Therefore, all our honors are bestowed according to world-wide standards. (Prizes are not honors.)

(7) Personal Decoration for Personal Achievements. The love of glory is the strongest motive in a savage. Civilized man is supposed to find in high principle his master impulse. But those who believe that the men of our race, not to mention boys, are civilized in this highest sense, would be greatly surprised if confronted with figures. Nevertheless, a human weakness may be good material to work with, I face the facts as they are. All have a chance for glory through the standards, and we blazon it forth in personal decorations that all can see, have, and desire.

(8) A Heroic Ideal, The boy from ten to fifteen, like the savage, is purely physical in his ideals. I do not know that I ever met a boy that would not rather be John L. Sullivan than Darwin or Tolstoy. Therefore, I accept the fact and seek to keep in view an ideal that is physical, but also clean, manly, heroic, already familiar, and leading with certainty to higher things.

(9) Picturesqueness in Everything, Very great importance should be attached to this. The effect of the picturesque is magical, and all the more subtle and irresistible because it is not on the face of it reasonable. The charm of titles and gay costumes, of the beautiful in ceremony, phrase, dance, and song, are utilized in all ways.

taken from Ernest Thompson Seton (1927) The Birch Bark Roll. The full text can be found at:

www.inquiry.net/adult_association/seton/bow/9_principles.htm

Ernest Thompson Seton drew on the thinking of writers like G. Stanley Hall, for example using his ideas around ‘recapitulation’ as a rationale for camping. According to Macleod (1983: 131) he came upon his Indian motif from two directions:

First, he was concerned not merely to preserve resources for man’s use, the reigning form of conservation, but also to defend the ecological balances of nature in the wild. The American Indian, he believed, had lived in harmony with those balances, whereas the white man destroyed them. Second, in reaction against his father, Seton exalted natural drives; this predisposition, combined with an interest in animal behaviour, led him to embrace Hall’s instinct psychology and the idea of boyish savagery. Yet instead of seeing ‘savagery’ as merely a rung on the ladder to civilization the way Hall did, Seton came to value Indian life as an end in itself, until by 1915 he proposed a Red Lodge for men to learn the spirit of Indian religion.

The approach he proposed used camping out and various ceremonies, games and awards. Significantly, Ernest Thompson Seton did not follow the usual path of character builders by ensuing the preaching of conventional morality. Crucially, he made all offices elective and looked strongly to the associational life of the group (see the above principles).

Ernest Thompson Seton made a significant impression on Robert Baden-Powell – and his thinking influenced the way in which he thought about the organization and shape of Scouting. He visited Britain in 1904 and 1906 to promote his work around woodcraft – and was later to claim that Baden-Powell had stolen ‘many of Scouting’s essential ideas from him’ (Rosenthal 1986: 71). Seton also believed that Baden-Powell’s use of ‘Be Prepared’ ‘was transparently a prescription for war, a commitment that in his view the entire Scout organization, in its activities, rhetoric and principles of unwavering obedience to Scout officers, shared’ (op. cit.). In short he believed that Baden-Powell had betrayed the spirit of woodcraft. His ideas also inspired splinter groups from the Scouts such as Ernest Westlake’s Order of Woodcraft Chivalry (formed in 1916) and John Hargrave’s Kibbo Kift Kindred (founded in 1920). The Woodcraft League of America grew to some 5000 members – but ‘organizational laxness and perhaps the eccentricity of Seton’s ideas barred sustained growth’ (Macleod 1989: 239).

Further reading and references

Macleod, D. I. (1983) Building Character in the American boy. The Boy Scouts, YMCA and their forerunners, Madison: Wisconsin University Press.

Rosenthal, M. (1986) The Character Factory. Baden-Powell and the origins of the Boy Scout Movement, London: Collins.

Seton, E. T. (1903) Two Little Savages, New York: Grosset and Dunlap (1911 edn).

Seton, E. T. (1906) The Birch Bark Roll of the Woodcraft Indians : containing their constitution, laws, and deeds, New York: Doubleday, Page and Co. Online (1927 version): http://www.inquiry.net/adult_association/seton/birch_bark_roll/index.htm

Seton, E. T. (1948) Trail of an Artist-Naturalist. The autobiography of Ernest Thompson Seton, New York.

Seton, E. T. (1949) The best of Ernest Thompson Seton / selected by W. Kay Robinson, London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Seton-Barber, D. A short biography of Ernest Thompson Seton, The Ernest Thompson Seton Institute, http://www.etsetoninstitute.org/BIOBYDEE.HTM, accessed June 12, 2002.

Wadland, J. H. (1978) Ernest Thompson Seton: Man and nature in the Progressive Era 1880-1915, New York.

Links

Ernest Thompson Seton Institute: useful collection of material on Seton and Woodcraft.

Acknowledgement: The picture of Ernest Seton is from the Wikipedia Commons who say: “This is a press photograph from the George Grantham Bain collection, which was purchased by the Library of Congress in 1948. According to the library, there are no known restrictions on the use of these photos”.

To cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2002). ‘Ernest Thompson Seton and woodcraft’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, [https://infed.org/mobi/ernest-thompson-seton-and-woodcraft/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K. Smith 2002