John Stansfeld (“the Doctor”) and ‘Oxford in Bermondsey’. John Stansfeld (“The Doctor”) gathered together a remarkable group to work with boys and young men in Bermondsey. Their work and subsequent contribution helped to define the shape of modern boys’ club work and social policy more widely. They were also a significant force in the Church of England. Here we review John Stansfeld’s contribution.

contents: introduction · the oxford medical mission · boys’ clubs · a change of direction · conclusion · further reading and bibliography · links · how to cite this article

John Stansfeld (“The Doctor”) (1854-1939) was born in Lincolnshire. His father worked in a bank and has been described as ‘a very loving Christian’ but ‘a poor hand at business’ (Baron 1952: 7). His mother, appears to be have been ‘a very good woman of affairs’ (op. cit.). He left school at the age of 15 to work in an engineering office, From there he had several jobs in the City before passing a Civil Service examination. At the age of 22 he began working in Customs and Excise (where he stayed for some 30 years.) After a while he transferred to the Oxford office and in his spare time he became an undergraduate of Exeter College. He had become set on taking Orders – and also joined Wycliffe Hall. He took his BA in 1889 and his MA in 1893. Having limited time he decided to read medicine sitting for his first MB examination in 1893 just before he was transferred to Glasgow. He was then transferred to London and attached to a distillery (meaning there was only 30 minutes work to do each day). He joined Charing Cross Hospital as a “spare time student” qualifying within a couple of years.

The Oxford Medical Mission

John Stansfeld had a strong evangelical sympathy. He was associated with ‘The Oxford Pastorate’ – essentially an evangelical reaction to the Oxford Movement – which was founded and steered by F. J. Chavasse, the Principal of Wycliffe College. He was invited to Bermondsey by a member of the group – Henry Gibbon – and Edwyn Barclay a key figure in the evangelical Layman’s Missionary Movement (and the head of a brewery close by Southwark Cathedral). After his visit they invited him to set up a medical mission. At this time the area of Bermondsey where he began to work (Abbey Street and Dockhead) was one of the poorest and most deprived areas of London. Work in what became known as the Oxford Medical Mission began in 1897 in a small house in Abbey Street. ‘The Doctor’ lived upstairs. No charge was made for treatment or medicines – but there was a box for gifts which largely paid the drugs bill.

The medical work provided only a limited outlet for the missionary activities of the young men who arrived from Oxford. A Bible Class was started. From there (following some disruptive activity on the part of local lads) they started orientating work towards boys and young men. The work grew quickly – and they took over an old corset factory (134 Abbey Street) in 1903. Downstairs was the dispensary, upstairs on the first floor a boys’ club. There were also rooms for resident missionaries on the top floor. John Stansfeld’s visits to Oxford Colleges attracted a remarkable collection of young men to Bermondsey to visit. ‘Come and live the crucified life with me in Bermondsey’ he invited one group (Baron 1952: 29). There is a picture of the officers at a summer camp (at Horndon in 1907) organized by Stansfeld. The group includes Geoffrey Fisher (later Archbishop of Canterbury), Alec Paterson (later Prison Commissioner); Barclay Baron (a key figure in the organization of Toc H) and Stansfeld himself. Other people associated with the work in the first two decades of the twentieth century included William Temple (Archbishop of Canterbury), Clement Attlee (later of the Labour Party and Prime Minister), ‘Tubby’ Clayton (who founded TocH) and Basil Henriques and Waldo Eagar – both later central figures in the boys’ club movement.

Boys’ clubs

As a condition for receiving free medical treatment young men and boys were asked to attend a Bible Class on the next Sunday. These classes became the centre of the work and it was out of these that clubs initially formed. He chose Fratres as the motto for the work. It was in Barclay Baron’s words ‘the epitome of his oft-reiterated phrase “We are all brothers”‘ (1952: 34). It described both the ideal of the mission – and the way of working adopted by the residents and workers. According to Barclay, John Stansfeld was clear that he had been ‘sent’ to Bermondsey to spread a gospel.

Its ‘Teaching’ was plain – that all mean are brothers as soon as they know God to be the Father of them all, and that the Way to brotherhood, the Truth about it and the Life of it are only to be found in Jesus Christ. (Baron 1952: 35)

The boys’ clubs had a strong emphasis upon ‘the lads making their own club’. This meant, for example, that it was they who regularly decorated and repaired the Abbey Street premises. Stansfeld also began to set up a series of group initiatives including a brass band (which made a lot of noise – but thankfully for the neighbours did not last long) and a club magazine – Fratres. He had a strong emphasis upon self-help. As Baron (1952: 220) put it, ‘If cash was short in the pockets of his men and boys, another resource was never in short supply – the gift of themselves, their spare-time, their ingenuity and skill, their love for the “family”‘.

The Abbey Street club drew its members largely from local streets – and the Stansfeld took the decision to expand the work into the poorest area of Bermondsey – Dockhead and the area that lay between it and the river (known as Jacob’s Island). It was this area that featured in Charles Dickens’ the famous passages concerning Fagin in Chapter 50 of Oliver Twist. The central residential area was then called London Street (now known as Wolseley Street). Of it lay a series of rundown and overcrowded courts somewhat ironically called Pleasant Row, Virginia Row and Pansy Row. It was close to these, in some derelict buildings bounded by Halfpenny and Farthing Alley and next to The Ship Aground public house, that Stansfeld set up the Dockhead Club. It was run by senior boys from the Abbey Street Club – Fred Gunning, Josh Jackson and Jim Ford. Baron describes then as laying the foundations well’ ‘with firmness, faith and unfailing humour’ (1952: 50) (assisted by residents). Other ‘branch clubs’ followed including Decima Street (run by a local man who had been a club member with the assistance of Donald Hankey) and the Gordon Club (initially in an old sausage shop halfway between Decima and Dockhead).

The Abbey Street club drew its members largely from local streets – and the Stansfeld took the decision to expand the work into the poorest area of Bermondsey – Dockhead and the area that lay between it and the river (known as Jacob’s Island). It was this area that featured in Charles Dickens’ the famous passages concerning Fagin in Chapter 50 of Oliver Twist. The central residential area was then called London Street (now known as Wolseley Street). Of it lay a series of rundown and overcrowded courts somewhat ironically called Pleasant Row, Virginia Row and Pansy Row. It was close to these, in some derelict buildings bounded by Halfpenny and Farthing Alley and next to The Ship Aground public house, that Stansfeld set up the Dockhead Club. It was run by senior boys from the Abbey Street Club – Fred Gunning, Josh Jackson and Jim Ford. Baron describes then as laying the foundations well’ ‘with firmness, faith and unfailing humour’ (1952: 50) (assisted by residents). Other ‘branch clubs’ followed including Decima Street (run by a local man who had been a club member with the assistance of Donald Hankey) and the Gordon Club (initially in an old sausage shop halfway between Decima and Dockhead).

John Stansfeld met and married Janet Marples in 1902. She was a volunteer worker at the nearby Time and Talents settlement. (Several other young men from the Mission were also to marry workers from Time and Talents). The daughter of a Sheffield master cutler, Janet Marples had trained as a nurse at the Middlesex Hospital. Children followed – and it became necessary for the Stansfelds to move initially to a house close by on Grange Road, and later to a building on Riley Street to which the the medical work had moved in 1907. They were later to return to Grange Road, Bermondsey.

Exhibit 1: Alec Paterson on the Doctor and the OMM (1910).

… the food was of the plainest. Hair shirts were too expensive, so ordinary ones were worn. Furniture was limited. The residents gave away all their clothes and dressed anew in the old-clothes cupboard. Bare boards and Windless windows were the fashion. So exposed were the bedrooms that men would dodge under the bed when dressing, and shave in a cupboard. It would have seemed chilly, but nobody was allowed to stand still or sit still long enough to notice anything. Blinds came from Reading and were cunningly hidden: a fragrant oilcloth rolled in from the West and was ruthlessly given away. The OMM was a stern ascetic brotherhood, deaf to the appeals of sisters and aunts. Nowadays we need not look far in search of an armchair, a curtain or a cigarette. But in 1897, the Doctor and his small band were laying strong foundations, and it is well that at the beginning the keynote of the Mission should have been clear and unmistakable. The utter abandonment of self to work, the simple concentration on a spiritual aim and method were high ideals and gave birth to a stern tradition, which the observer may still detect beneath the smoothness of a more ordinary life.

In the lower rooms, medical work reigned supreme for a year. The Doctor then determined to start a Bible-class for boys. A Sunday came when two boys were fighting outside the very door of the Mission. The Doctor hid behind the door, waited his chance, rushed out and seized both unawares, dragged them in, gave out a hymn, while they were regaining breath, and thus the Bible-class began. This was not enough. The streets were full of boys every night, whose spare time was being wasted, whose characters were being formed by any chance combination of instinct, passion or convention. Every evening from the Mission windows (and especially when they were broken) could be seen a procession of boys in noisy gangs on their way to the Star Music Hall at the top of the street.

A Boys’ Club was declared essential, a pair of gloves and a bagatelle table were hurriedly procured, and the ground-floor was invaded by a crowd of ready members. The Doctor sat seeing his patients each evening behind a screen; on the other side was rampant boyhood. Now and then the Doctor would think the tumult beyond the limits of family life, and would dodge round the partition, wave a thermometer, and eject two of the biggest without mercy. Even in these early days it was the custom to close the Club each evening with family prayers, and the Sunday Bible-class grew to such a size as to make these first headquarters seem very small. A shed was built at the back, but this was in its turn too small for the numbers of boys who were taking refuge in this small Mission.

Opposite was an old corset factory, big and ugly, with strong floors and large rooms. The rent was stiff, but the Doctor was inexorable, and a move was made to the new building, which was six times as large and quite as uncomfortable. Here the big Abbey Street Club sprang into being, every room humming with life, and the Doctor in a white coat dealing with a growing stream of patients on the ground-floor. On the top floor, wooden partitions grew up, and produced a number of small bedrooms. Oxford men began to trickle down a little faster, and soon counted themselves lucky to secure a bed.

The Doctor visited more and more patients, kept up his Government work in the City, filled the large Club Chapel on Sunday afternoons, plotted a few economies and many extensions, dreamed of camps and convalescent homes, and was never content.

All this time the Doctor earned his living as a clerk in the Civil Service. He fed on biscuits and out of paper-bags, and came home in the evenings, wearing the silk hat then obligatory on City men and Government clerks, to talk very quickly and simultaneously plans and persons, methods and hopes—but he was out of the house again in ten minutes, wearing his silk hat now as the badge of doctorship, to attend the dispensary, to look into the Club, to visit the sick and dying into the small hours and to be off punctually next morning to his bread-winning job. The finance of the Mission was totteringly unsound. “What we have got to do”, said the Doctor in a rush of words, “is to do more work. There are hundreds of boys in Dockhead completely neglected. The Abbey Street boys are civilised now. They must go out to Dock-head as missionaries.” Four boy-officers went. Dock-head, home of Bill Sykes and Nancy, lived up to its reputation. ‘Rough houses’ were the order of the day; the door was a scene of constant fights. Evening prayers were sometimes a riot; but sometimes they were not. The Doctor slipped in during the evening, perhaps to take prayers himself and always to stay afterwards to advise, consult and pray with the officers. When they were nervous and discouraged, he would say: “Friction is a sign of life. Don’t be afraid. Here are all these boys and God is in every one of them.”

Slowly but perceptibly something new crept into the outlook of many Bermondsey boys. ‘Rough houses’ fell out of fashion. Sport, and particularly boxing, was seen to be possible and more attractive. Club members themselves quelled riotous outsiders and brought them in.

Alec Paterson (1910) The Doctor and the OMM, London: Oxford Medical Mission

A change of direction

In 1909 Stansfeld announced that he intended to take Orders – and within a year he had been ordained and taken up the incumbency of St Anne’s, Thorburn Square, Bermondsey. The impact on the work was significant. Not having a medical superintendent, the medical mission had to be wound up. The work now focused on the boys’ clubs and the adult activities that flowed from it. There was also a change of name to the Oxford and Bermondsey Mission (OBM). The residents launched an appeal for a Stansfeld Commemoration Fund – which became the basis of the Stansfeld Club (opened in 1911). This was adult provision for the boys’ club ‘old boys’ – many of whom either still came to Abbey Street and the branch clubs – but who needed a different environment. The Club was established at 134 Abbey Street – and the boys’ club When the First World War came many associated with the Club – both members and residents – joined the local territorial battalion. As Baron (1952: 174) notes, many who went to war did not return (in fact 120 died). During the war the clubs limped on. After the war the Stansfeld Club relocated to an Old Methodist Church in what became known as Hankey Place (named after Donald Hankey who died leading his platoon to the attack on the Somme in 1916). The Mission also changed its name to the Oxford and Bermondsey Club.

In 1909 Stansfeld announced that he intended to take Orders – and within a year he had been ordained and taken up the incumbency of St Anne’s, Thorburn Square, Bermondsey. The impact on the work was significant. Not having a medical superintendent, the medical mission had to be wound up. The work now focused on the boys’ clubs and the adult activities that flowed from it. There was also a change of name to the Oxford and Bermondsey Mission (OBM). The residents launched an appeal for a Stansfeld Commemoration Fund – which became the basis of the Stansfeld Club (opened in 1911). This was adult provision for the boys’ club ‘old boys’ – many of whom either still came to Abbey Street and the branch clubs – but who needed a different environment. The Club was established at 134 Abbey Street – and the boys’ club When the First World War came many associated with the Club – both members and residents – joined the local territorial battalion. As Baron (1952: 174) notes, many who went to war did not return (in fact 120 died). During the war the clubs limped on. After the war the Stansfeld Club relocated to an Old Methodist Church in what became known as Hankey Place (named after Donald Hankey who died leading his platoon to the attack on the Somme in 1916). The Mission also changed its name to the Oxford and Bermondsey Club.

Early in 1912 John Stansfeld and his family moved out of Bermondsey to take up a living in a poor parish in Oxford (St Ebbes – part of the Oxford Pastorate). Like many of the former residents who had families, as their children grew older they found it difficult to stay – both on health grounds and because of the quality of the environment. Stansfeld’s daughter, Janet suffered from tubercular glands – and he decided to ‘take his family into cleaner air and more open space before it was too late’ (Baron 1952: 66). Baron continues, ‘Nothing less would have moved him’.

Stansfeld served at St Ebbes, Oxford until 1929 when he was given a country living at Spelsbury (close to Charlbury). During this time he had become very involved in missionary work (with some of his old Bermondsey colleagues. John Stansfeld’s wife – Janet – died in 1918. His son – Gordon – who lived in Bermondsey for a time but then went to work in Borstals died in a tragic accident in 1931 (he was working at a training school in Burma, got caught in some nets and drowned). Stansfeld himself died in 1939. He was 85.

Conclusion

John Stansfeld was able to gather a remarkable group of men around him in Bermondsey. They were to make a significant impact not just on boys’ club work – but on social policy generally. As a doctor, worker and priest he also had a very direct impact on people’s lives. Along with a group of other doctors (Alfred Salter, Selina Fox – both physicians; and Scott Lidgett – the theologian and Methodist minister who was warden of the Bermondsey settlement for 60 years) Stansfeld had a longstanding effect upon Bermondsey. A small housing estate now bears his name – but his influence is now largely unseen.

Further reading and bibliography

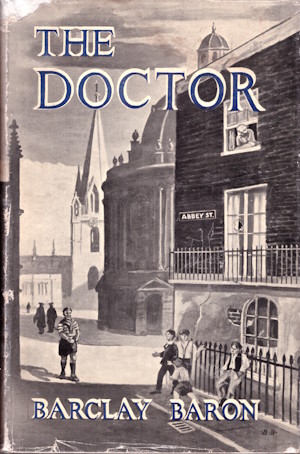

Baron, B. (1952) The Doctor. The story of John Stansfeld of Oxford and Bermondsey, London: Edward Arnold.

Eagar, W. McG. (1953) Making Men. The history of boys’ clubs and related institutions in Great Britain, London: University of London Press.

Paterson, A. (1910) The Doctor and the OMM, London: Oxford Medical Mission

Links

See the infed feature – Oxford in Bermondsey.

Acknowledgements: Picture: Blue plaque for John Stansfeld by Owen Massey McKnight ( addedentry) and sourced from Flickr (addedentry/4522466233). Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) licence.

How to cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2004). ‘John Stansfeld (“the Doctor”) and “Oxford in Bermondsey”‘, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/john-stansfeld-the-doctor-and-oxford-in-bermondsey/ Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K. Smith 2004