Marie Paneth (1895 -1986) was a talented painter, art therapist and pedagogue. Her book, Branch Street, is a classic examination of community-based work with children. In this piece, Mark K Smith explores her work and continuing relevance.

Contents: introduction • early life and family • New York • London and Branch Street • The Windemere Children and Rebuilding Lives • Rock the Cradle • later life • Marie Paneth’s pedagogy and use of art • conclusion – on personality • resources • references • acknowledgements • how to cite this piece

Introduction

Marie Julia Paneth (1895-1986) was a talented painter, art therapist and pedagogue. Her book, Branch Street (1944) is a classic exploration of community-based work with children during the Second World War – and the healing use she made of art – both with The Windemere Children (2020) and in later practice – was pioneering. Her approach was based in pedagogy and an appreciation of therapeutic practice. In this piece, we explore her work – mostly in the 1940s – and its continuing relevance.

Early life and family

Marie was born in Sukdull (near Wurzing), Austria on August 15, 1895, into what appeared to be a prosperous Jewish family. Her father, Alfred Fürth, was part of a family that owned a large fez factory in Strakonitz in Bohemia. However, it seems that all was not well financially. When he died in 1899 at the age of 40, Marie’s mother (Marie Jeiteles 1869-1950) was left with four young children (Walter, Marie, Hans Johann and Gertrude) and no visible means of support except for the generosity of relatives. Luckily, help was forthcoming from the Jeitelites (Ulrich 2018 – see, also, geni.com and Yivo Institute, undated).

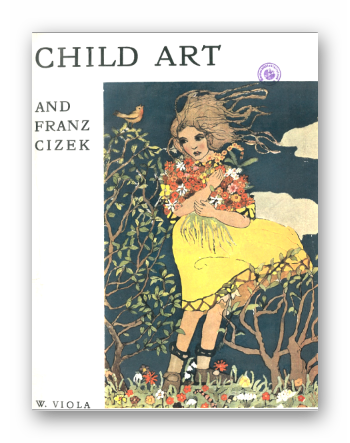

While she talks about her education stopping at Matriculation ‘after spending six years in a Lyceum in Vienna’ (Paneth 2020: 45), Marie also studied there under the painter Franz Cižek (1865-1946) an Austrian genre and portrait painter. Cižek, as we will see, had a significant impact on the way she used art with children and young people. Known for popularizing the term ‘Child Art’ and developing a more creative art pedagogy, he also helped to build the Child Art Movement that came to prominence in the 1920s.

Marie Fürth was tall (6ft. 1in.) and a ‘great beauty’ (Ulrich 2018.). In June 1918, she married a doctor – Otto Paneth (1898-1975) – in the Evangelische Pfarrgemeinde A.B. Wien-Hietzing. Otto was a son of Joseph Paneth (1857-1890) a physiologist whose work included studies of cells that provide host defence against microbes. It was because of Joseph Paneth’s earlier friendship with Sigmund Freud that Marie came to know Freud in the period before moving to the Dutch East Indies with Otto. Joseph Paneth was also known for his correspondence with philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

After the end of the First World War, Marie and Otto appeared to have moved around – probably as there were few jobs available in Austria. In 1919 they had a daughter Brigitte (born in Vienna, Fairfax County, Virginia, United States) who was later (in 1941) to marry and live in Oxford with the architect Bruce Watling. In 1921 the family was in Amsterdam in the Netherlands, where they had a son Matthias (who became a heart and lung surgeon and finished up as chief surgeon at the Brompton Hospital, London). They moved on to Indonesia (then the Dutch East Indies) and had another son – Anton – born in 1926 in Sumatra. Anton also became a doctor, but tragically committed suicide in February 1955 (his wife Dulcie had died a few weeks before) (Daily Herald, February 15, 1955: 5). Anton and Dulcie were buried together in St George’s churchyard, Crowhurst, close to where they had lived, and were joined by Anton’s sister Brigitte in 2002.

Marie and Otto’s marriage broke down in the second half of the 1930s and they were later divorced (Ulrich 2018, Geni 2020). Otto Paneth stayed on in Kaban-Dajhe (DEI) for a time but eventually moved to the United States in 1951.

New York

Marie Paneth returned to Europe and appears to have been in Paris in 1938. She left France later in that same year for New York. It is possible that it was around this time that she also began a ‘great love affair’ with Heinz Hartmann, the famous psychoanalyst/psychiatrist (Ulrich 2018). Elizabeth Jane Howard (see below) spoke to him in 1946 and reported that he ‘was extremely glad to have news of Marie, whom, clearly, he loved’ (2002: 188). Hartman had been a pupil of Sigmund Freud in Vienna and had undergone analysis with him. Leaving Austria with his family in 1938, he arrived in New York in 1941 via Paris and Switzerland. Heinz Hartman, along with Erik Erikson were key contributors to the development of ‘ego psychology’ within psychoanalysis (Isbister 1985: 244) following a founding contribution by Anna Freud The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence (1937). Anna Freud also helped to legitimate child analysis in the psychoanalytical movement (Isbister 1985: 244) and was to become a friend of Maria Paneth (Avery 2020).

In New York, Marie exhibited in the 1939 Society of Independent Artists (SIA) show (Ulrich 2018). The Society, formed in 1916, set out to provide progressive artists with an opportunity to show their work through an annual exhibition. The SIA set itself against the more conservative National Academy of Design. SIA shows were modelled of the French Salon des Indépendants, without jury or prizes (see Weininger 2020). However, Paneth was only to stay in New York for seven months at this time – sailing for Southampton, England at the beginning of July 1939.

London and Branch Street

Marie Paneth spent much of the Second World War in England and did various jobs. When she entered the UK she was listed as a ‘female enemy alien’ but following an appeal was exempted from internment and classed as ‘non-refugee’. Her occupation was listed as ‘Artist Painter’, but she first found work as a matron in Scotland at Gordonstoun School, Elgin with Kurt Hahn (National Archives HO 396). After several months she returned to London and, amongst other things, learnt to type. Whilst doing this she became friends with Elizabeth Jane Howard who was, at the time (1941/2) working as an actress and model (but who later achieved fame for her novels – and her marriages to Peter Scott and Kingsley Amis):

We had hardly been at Pitman’s for a week before we both noticed that there was one student utterly unlike the others. She was far older than any of us, very tall, with iron-grey hair that fell carelessly across the side of her high forehead. She had the most ravishing smile, became a beauty on the instant. She had a kind of seductive liveliness, an inward amusement at anything we said. She carried her remarkable appearance with an assurance that fascinated both of us. She was Austrian, she told us, a refugee now living in England. She was, or had been, married to a Dutch doctor and had spent much of her married life in Malaysia. She had three children who were here too: Matthius was training to be a doctor, Brigitte was married and lived in Cambridge, and Tony was at Gordonstoun School. She knew Kurt Hahn who’d started a similar school in Germany. She was a painter, and she wrote. Her name was Marie Paneth. She used to enjoy amazing and shocking us with her stories, and when she’d finish we’d cry, ‘Oh, no, Marie! Surely not!’ and she’d laugh and say, ‘Oh, yerse! That is how it was’. We felt excited and proud to know anyone so unusual and exotic. (Howard 2002: 113-4)

Thomas Ulrich (2018) has described his experience of Marie Paneth (who was his aunt) as follows, ‘Being so talented she was a difficult person and quite intimidating for me when I knew her as a child during the war’.

Marie Paneth lived in Chelsea and later in Hampstead. She began to work with children and young people in five London boroughs (in six different projects) (1944: 122). Some of this activity was based in deep shelters in the East End of London, particularly those organized in the Underground Stations. Often her fellow workers were conscientious objectors (often linked to a Pacifist Service Unit or Quaker organization) (Starkey 2000). Her book, Branch Street (1944), focuses on her work in a play centre that began in what had been a surface bomb shelter. It was no longer in heavy demand once the Blitz had finished in May 1941 (see Jeffs 2003). The project was later based in a condemned house loaned by the borough council. Paneth described her task as keeping ‘the children busy during the long blackout evenings’. Many of the children and young people she worked with had been written off by teachers and social workers; were at odds with their peers in different streets; and/or suffering significant poverty, poor health and family breakdown. The challenges she faced caused her to reflect on the situation and the work – and she recognized the need to communicate with others about it. Branch Street is full of vivid stories. Through these stories, Marie Paneth grapples with the nature of the work, the needs and experiences of the children and young people she encounters, and her feelings as a worker. It is all done with rare honesty and a breathtaking directness.

The location of Branch Street is disguised in the text – and trying to work out where exactly in London it was has been, and is, an interesting diversion. Betty Martha Spinley (1953: 41) says it was in Paddington – and this is confirmed by Elizabeth Jane Howard’s recollection of her conversations with Marie Paneth (2002: 168). The area appears to be somewhere in the old wards of Westbourne and Church close to Paddington Station (which includes the district between the Edgware Road and Lisson Grove [NW8]). The latter was the site for much of the detached work project later analysed by Goetschius and Tash (1967) in Working with the Unattached.

If you have been involved in street and club work with children and young people, then you are likely to recognize the situations Paneth describes. There is the testing out through talk of sex and your sexuality; the trip to the zoo where members get ‘lost’; the camping trip which is a major strain on the worker; being threatened; the stealing from the project; and the arrival of a new worker who is a wrestler. It is difficult to think of a book concerning work with children and young people where such stories have been better told. There is also a significant historical point here. While there had been excellent accounts of the sorts of encounters workers have with young people (e.g. Maud Stanley on work with girls; or Charles Russell on boy gangs) – Marie Paneth tells it directly, and in the language used at the time.

As Tony Jeffs has pointed out, details of how the programme ended are not supplied.

A first edition of the book appeared in July 1944 so we can assume it was late 1943 or early 1944. Paneth tells us a new organisation intended re-opening the house as a centre to be used exclusively by five to eight-year olds. We know that when Spinley arrived the local settlement provided a range of well-established youth clubs (2003: 94).

Branch Street received enthusiastic reviews and was reprinted within three months. John Betjamin, writing in the Daily Herald (July 26, 1944: 2) with the headline ‘We let this happen to dead-end kids’, concluded that ‘this is a book of the utmost importance, written shortly, graphically and calmly’. He didn’t agree with all of her approach, but recognized her patience, courage and desire to bring fuller life to those involved. As Tony Jeffs (2003) has noted, ‘sixty years on it is perhaps more widely cited by art therapists than youth workers’. Paneth ‘justifiably attained recognition as a pioneer in that field (see Hogan, 2001). Such indifference is a tragedy as Paneth serves up a dazzling exposition of the dynamics of youth work practice’ (op. cit.).

Windemere and rebuilding lives (the Windemere Children)

Three months after Germany and Austria were occupied by Allied Forces, a number of Jewish children (many Polish) were brought from camps to the UK. They were flown on Sterling bombers to Carlisle – a twelve-hour flight. Most were aged between 8 and 15 years, but six three-year-olds also arrived on the last plane. Marie Paneth was one of the team working with them. ’Blighted and seared in mind and soul though their muscles were strong’, she wrote, ‘these victims of Nazi corrosion had to be taught again to be children and human beings. But the question was how?’ (1946: 53). She continued:

On the gentle shores of Lake Windermere, one of England’s most beautiful, the busses arrived late at night with 300 of these children. As the busses spilled them into our arms they were talking. Talking, talking, talking, a frenzy of talking horror. They had lived a cadenza of horror that would have finished off any of us, and it was as if they wanted to give us their credentials by talking. It was a nightmare. There was no stemming the flood. Excitedly, but unemotionally, they rattled off their tales, while without the slightest unruliness they did what they were told: undressed, were inspected by the doctors, waited, had baths, went to bed.

The work in the camp – which was to last four months – was directed by Oskar Friedmann (1903-1958) a Jewish German social worker and psychoanalyst who had initially trained as a teacher. Another key figure was Alice Goldberger – the former superintendent at Anna Freud’s Hampstead Nurseries (Freud 1951). Friedmann had spent time in a concentration camp himself and had a concern with the welfare of children. As a child, he had been placed in an orphanage and had experienced an exceedingly tough time until he moved to another (Winnicott 1959). Now a refugee from Berlin, Friedmann had been working with The Central British Fund for German Jewry providing mental health care for young refugees. ‘He passionately believed it would be possible to bring these children, who had witnessed such extreme horrors, back into civilised society and he made it his mission to do so’ (World Jewish Relief 2020). Anna Freud helped to develop the approach taken with the younger children and worked with the group of six after they left Windemere (see Anna Freud with Sophie Dann 1951).

The overall approach to rehabilitation taken in the reception camp was that it would be useless to try to enforce orders.

We meant to make a few necessary rules, which might or might not be carried out. We were ready to face many major and minor disasters but were convinced that the most necessary part of our task was to keep the children clear of any feeling of pressure by authority.

This attitude, successfully built up by the whole community, produced admirable results. I ascribe the fact that no major disaster occurred to this lack of pressure and the resulting atmosphere of ease. None of the boys or girls committed suicide in these critical weeks; none killed any other; nobody got seriously ill; nor were there any serious accidents. On the other hand, the straightforward outspokenness of their conversations with us showed their trust in the sanity of their surroundings. (Paneth 1946: 54)

It was in this context that Marie Paneth worked – using art with 48 of the children. Her method had elements of the approach taken in Branch Street. The work is described in a press release from the New York Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) for an exhibition of their work in 1948.

The studio was open to them every afternoon, and Mrs. Marie Paneth, who was in charge, made materials available in a congenial and friendly environment. Other studies were offered at the Center, and those young people, although usually restless and boisterous in their other classes, were quiet and spoke in whispers in the art studio, Eventually the subject matter of past experience, which seemed constantly to recur, brought back memories apparently too painful, and they ceased coming.

A few of the pictures depict the concentration camp, or symbolize the students’ attitude toward life, but on the whole they chose subjects from fantasy or observation, such as pleasant landscapes or formal patterns. Twelve of the young people had become tuberculosis cases. A comparison of their work with that of the more healthy ones shows that they never drew on past experience, but made exclusive use of symbolic material which may be interpreted as directly relating to their illness.

The project was based in a former war workers’ hostel on Calgarth Estate – which was located at Troutbeck Bridge near Windermere (click to view on a map). It became the subject of a feature-length film/drama produced for the BBC by Wall to Wall, Warner Bros. and ZDF – The Windermere Children – and aired in 2020.

Marie Paneth summed up the work as follows:

Here is our task—to make life worthwhile for them; to make them find a positive answer to “what for”; to make them fit to live in a normal society anti enjoy normal life.

What they have to learn, and indeed, are rapidly learning, apart from the subjects which school can teach, is what life under normal conditions teaches our children. That truthfulness is essential and punctuality necessary where people live in a community. That outside their group comradeship of “we three hundred together” there are people who mean well. They must learn to forget their misery. What they must get from us is a sense of security and continuity in their personal relationship, in their environment, and in their training. And last, though not least, we must give them happy experiences worth remembering. (1946: 55)

Some of the children involved in the art groups later travelled to New York to be with Marie Paneth at the launch of the MoMA exhibition featuring their work.

Click to view the MoMA exhibition – see image 7 for a picture of Marie Paneth with the children

Examples of this material are held in the Marie Paneth section of the Sigmund Freud Collection, Library of Congress. Mark Hartsall (2020) provides snippets of what is included and publishes a photograph showing Paneth with her young women pupils [their names inscribed on the front and notes of thanks on the back]. Art, Paneth wrote, ‘allowed these children to express through a medium other than words things that cannot be said in words’ — in images that, seven decades later, still haunt (op. cit.). Also included among her papers are short stories and an autobiography. The latter is called Fälschung (Fake), and ‘recounts her childhood in Vienna, Austria, her art studies with Franz Cižek, and her early married life in the Dutch East Indies’ (McAleer 2010). Mary Adams (2020) has commented:

One can only wonder at this title, “Fake”’. She herself relentlessly fought to stay true to her psychoanalytically-informed principles. ‘Fake’ has an emphatic anger to it not evident in the gentle, questioning, reflective and humorous narrator of Branch Street.

Rock the Cradle

In some respects, the most interesting item in the Library of Congress papers is a draft of an unpublished book dealing with the work Marie Paneth had undertaken in 1946/7. It provides further insight into her practice as an educator and psychotherapist. The manuscript, titled Rock the Cradle, ‘relates stories told by the children about their experiences in concentration camps, their adjustment to life in the British reception camp, and the ways artwork provided a nonverbal outlet for their emotional trauma’ (McAleer 2010). Following the showing of The Windemere Children on television, the book was finally published (Paneth 2020). It opens with the arrival of the children, and their Windemere experience. As such, some of the themes explored in her Free World article published at the time and discussed in the last section (Paneth 1946) are amplified. By this juncture however, it was clear to her that the children did not need pity, ‘but steady interest; no promises, but a rigid promptness in the execution of plans; and not protection, but readiness to help’ (op. cit.: 41).

The bulk of what follows is concerned with post-Windemere work. Paneth had been asked if she would teach eleven of the girls from the camp who had been housed in a North London hostel, ‘among other refugee youngsters who had spent the entire war or longer there’ (op. cit.). Her experience of this, and her learning from it, were her main reasons for writing Rock the Cradle (2020: 43). One of the strong themes emerging from her work with this group was the extent to which their early experiences of family life had been of great significance. Their capacity to recover from their experience of Auschwitz, and the appalling treatment they had been exposed to in Nazi concentration camps, was enhanced by their early upbringing.

[W]hat you learnt in the first few years of life was so strong it could withstand all life’s attempts to teach something else later. In their case, all the goodness and warmth, the order and friendliness, the shelter and protection, the general feeling that the world is good, which they had learnt when they were very small, had not been wiped out by everything they had gone through. (2020: 91-2)

What is also clear is that the steps these young women took toward recovering hope, and the possibility of living good lives, also owed a great deal to Marie Paneth’s capacity to gain their trust, appreciate their condition, and work with them to re-expand horizons, engage, reflect and act. When Rock the Cradle is added to Branch Street, we get a more sophisticated picture of her thinking and pedagogic practice and the extent to which it is based on the character, enthusiasm, and education of practitioners. We will return to this after discussing her later years.

Later years

New York and France

Marie returned to New York in the early 1950s, living initially close to Central Park on East 93rd Street. She became known as one of the earliest exponents of art therapy and earned her living working with psychiatrists and facilitating drawing by their patients. She was also exploring different dimensions of her work. The Marie Paneth collection includes substantial notes on:

- the Phenomenon of Drawing, circa 1958-1964

- Observations Grouped Around the Functioning of Visual Memory, 1957

- Picture Making When Toddlers Begin to Draw, undated

- On Trauma and Motility,” 1957

Also included in the papers are several works of fiction including short stories.

During this time Marie Paneth frequently returned to England to see her family. She also moved to Midtown Manhattan (300 East 37th Street). At least three exhibitions of her paintings took place in New York (Paneth 1955, 1958 and 1963) and another at the Galerie Marcel Bernheim in Paris (Paneth 1956). She made enough money from her work and painting to buy a farm near Grasse in the hills north of Cannes where, eventually, in the late 1960s, she went to live and paint full time. Even when she was over eighty, she had at least one one-woman exhibition in Paris (Ulrich 2018). Her work also appeared in exhibitions focusing on Austrian artists.

Marie Paneth eventually returned to London and the Hazlewell Nursing Home, Putney. The home was a few minute’s walk from where her son Matthius and his wife Shirley lived. She died on November 30, 1986. Marie Paneth was ninety-one.

Paneth’s pedagogy and use of art

It is possible to approach Paneth’s work with children and young people from within several different professional frameworks. She could be described as a social worker, youth worker, playworker or art therapist. However, probably the most useful starting point is where the social pedagogy tradition meets the therapeutic.

To begin, it may be helpful to consider some characteristics of social pedagogy. It is:

- A form of pedagogy and as such is rooted in education – and the philosophy of people like Rousseau and Pestalozzi.

- Holistic in character – as Pestalozzi says, there is a concern with head, heart and hand.

- Concerned with fostering sociality

- Based on relationship and care.

- Oriented around group and associational life (in contrast to much social work in the UK). Educators become part of the lifeworld of those involved. (Smith 1999-2019)

All five elements feature in Paneth’s account of her work in Rock the Cradle. She had quickly grasped that ‘what these victims of catastrophe needed more than else was a new sense of security’ (2020: 43-4). Marie Paneth continues:

The girls had lost all sense of direction in both a physical and emotional sense. We knew that the greatest need when leaving a concentration camp, even for an adult, was to know that the fact you were saved and alive was important to at least one other person in the wide world. This one other person could point the compass in the right direction for their ship to be steered across the high seas, but without this, any further voyage would be directionless. We could not give them this vital one person, but we could help these young people find roughly where they stood in space and time; geographically, historically, physically and biologically.

Ilse Korotin and Nastasja Stupnicki in their work on Austrian scientists and researchers label the work described in Branch Street as a sozialpädagogischen projekt (as could much of that in Rock the Cradle). They comment that Paneth’s:

… educational method deviates greatly from the educational ideals of the time. She advocates a relaxed, anti-authoritarian approach and lets the youngsters act out their angry and violent outbursts in order to achieve a cathartic effect. [Marie Paneth] urges her workers to allow the youngsters to express their anger out until they are fed up with it themselves. Like her children in other institutions, she gives her protégés material for independent, rule-free painting and drawing. This Cižek-inspired approach to children’s art drawing fails for the first time on Branch Street and results in attacks against the facility and the educators. When the children destroy the playground, the workers quit. However, [Marie Paneth] maintains her method and lets the children play as they have learned on the street. She presents them with a bombed-out place where everyone can build a new playground together with the building materials they have collected. Furthermore, they build a fire pit, a self-managed cafe and the like. The participatory Branch Street project uses the child’s game to build and maintain community. The young people can identify with a common place and a common project and, by taking on responsibility, build something new in the bombed and destroyed places of their city. (translated from Korotin and Stupnicki 2018: 669)

The ‘Cižek-inspired approach’ mentioned here is described by Mary V Gutteridge after visiting one of his classes as follows:

Cizek began his children’s classes as early as 1903. From the beginning all was free and experimental, the children choosing their own materials, with nothing in the way of a copy or a model. And free and experimental they continued and remained, as I was to observe in 1929, twenty-six years after the classes began. [click to read more]

This is how Cižek described his work:

The Juvenile Art Class is not a school, it is a work centre to which the children come of their own free will and where they can work just as their talents and inclinations prompt them. My educational task consists in furthering the creative giving of form and preventing imitation and copying. A drawing or any other product of a child is good, if the work accomplished accords with the child’s age and is altogether uniform in quality and when it is honest and true in every single detail.

I am the friend of my pupils. They are my fellow-workers and I learn from their work. (Viola 1936)

Marie Paneth did not, at first, use the term ‘art therapy’, nor ‘child art’, but she had developed a method of using art with ‘difficult’ children and young people ‘with much success’ (Hogan 2001: 293).

Roy Kozlovsky (2006: 8) has also commented that the approach that Marie Paneth took when responding to the ‘failure’ of the art activity is based on the work of another Austrian, August Aichhorn.

This strategy that promotes anarchy rather than enforcing discipline. Following Freud, he argued that aggression is unconsciously aimed to provoke punishment, which then justifies the hate one feels to his parents, and by extension, to society. The refusal to punish or condemn frustrates the delinquent’s expectations and destabilizes his relation to authority. Aichhorn allowed his subjects ‘to work out their aggression’ to the point of explosion: When this point came, the aggression changed its character. The outbreaks of rage against each other were no longer genuine, but were acted out for our benefit. Aichhorn builds on the make-believe quality of play, its self-reflexivity, to purge his subjects of their aggression through play….

Paneth allowed violence to rage without imposing limits, but rather than achieving catharsis, her group destroyed the play centre, and her staff quite. This failure brought about a change in Paneth’s outlook. Once she began to work with the children on their own turf, their behavior changed and their aggression diminished. (op. cit.)

There are several points to highlight here about Marie Paneth’s practice.

She draws on both pedagogic and psychoanalytical understandings

Paneth draws on both pedagogic and psychoanalytic understandings to shape her response to situations. More specifically, some of these insights are rooted in Austrian debates and explorations of the 1920s and early 1930s – before the impact of National Socialism. This was a period when Vienna was home to Sigmund Freud and to investigations of psychoanalysis which Marie Paneth was very much aware of. At the same time, and involving some of the same people, social pedagogy was emerging in Austria. It was, ‘linked to the establishment of a state policy on child-raising that sees the problems of children and young people as child-raising problems resulting from social problems and unfavourable living circumstances’ (Sting 2018: 110). Last, as we have seen, she drew on Cižek’s pedagogical approach.

She addresses issues with upbringing and the social environment

At the centre of the developments in thinking about social pedagogy in Austria were August Aichhorn and Siegfried Bernfeld. They ‘worked on a theory of waywardness and endeavoured to reform children’s residential care in the 1920s’ (op. cit.). This ‘waywardness’ was seen as largely a problem of upbringing. Aichhorn (1972: 97–98) describes child-raising as an ‘art’ that ‘requires a certain level of ability (involving, e.g., impartiality, catering to individuality, understanding, and empathy), but in which the significance of psychology is often overestimated’ (Sting 2018: 111). Paneth believed that the children that she was working with in Branch Street had missed out in significant ways – and that their indiscipline and aggression were a result of this. They were ‘hurt people’, people who lived ‘in an atmosphere which, though outspoken and tough in many ways, is secretive and untruthful on essential points’ (Titmus 1950: 123–4. See, also Welshman 2004). In Britain, others, linked to the Quakers Camp Committee, had been explicitly working with ‘wayward adolescence’ and developing approaches that were like Paneth’s and Aichnorn’s (see Wills 1941). Influenced by Paneth’s work, Ruth Wills and W. David Wills went on to develop their version of art therapy in the Barnes Project in Peebles (see Hogan 2001: 296; and Wills 1945).

The experiences that the children and young people faced on being liberated from the concentration camps – and that Paneth and the others had to work with – can be seen, on one hand, as an extreme version of those faced in Branch Street.

It seemed as if the Nazis had succeeded in wiping out of the minds of these boys and girls any capacity for planning the future, perhaps any wish for the future, or any belief in the reality of its ever becoming the present. For six years of their young lives, that future held so many possibilities to be feared and so few, if any, of pleasure, that the mechanism of planning, of remembering the plan and of an effort of will to execute it, seemed to be completely out of gear. They had been successfully trained to forget about the future. (Paneth 1946: 54)

However, what we also see in Rock the Cradle is the extent to which Paneth believed the subsequent recovery and growth of many of the young people was based in their early experiences of family life.

They had experienced so much, and that had made them wiser. In trying to stay alive, they had been especially resourceful and adaptable, understanding and ready take reality for what it was – grim though it might be. They had managed abd learnt and grown through their experiences; they had not only suffered. They were capable of coming out at the end with qualities, which could only be understood by accepting the fact that ten or eleven years, as in their case, of living in good, happy families, with parents and brothers and sisters, where they learnt what was good and how people lived together, had made the good in them so strong, it could withstand all the evil of their experience in th camps. (Paneth 2020: 75)

She hadn’t expected this to be the case. They had a base that allowed them to develop an appreciation that what was in the camps abnormal.

She focuses on relationships

Marie Paneth’s task in Branch Street, and that of those who worked with her:

… started by letting them behave in as “young” and undisciplined manner as one expects new born child to behave, as if they were absolutely irresponsible creatures, whom one had to accept as such. In this period of our acquaintance they had to find out that we were utterly unconcerned about their behaviour but enormously concerned with being “on their side”, seeing their side of the question, bringing them things which they might want or need, so that they might find out and become convinced that we were really for them, irrespective of what sort of persons they were. We had to continue in this way until we would be sure that the children had understood and had accepted us for what we were. (1944: 47)

Through this process, she hoped that the children would develop self-discipline. However, this was not an easy process. The world she had inhabited was very different from theirs – and there was considerable animosity to her nationality at times (she was technically a ‘registered alien’). It took considerable patience and courage to stay alongside and engage with them. Yet she found the resources to persevere.

At Windemere, there was another level of problem. Truth had been subordinated to survival. In the concentration camps, the children had ‘to lie about the most fundamental facts to keep alive’ (Paneth 1946: 55).

Everything depended on instinct… Only the fittest could survive… Picked by the Nazis for their physical toughness, picked by fate as those who had the greatest will to survive, to live, they are here now, with us in Britain. (op. cit.)

Paneth comments that the children ‘soon discovered that survival was one thing—and living, another’ (op. cit.). By the time she was working with the young women in North London, we see the relational element of the work developing more clearly.

The kind of teaching I had done was not just about transmitting facts. Teacher and pupils had also become aware of attitudes towards life and its problems. Through my approach, it seemed they had started to like and trust me, just as I had started to like them. Now we wanted to know more of each other. I also felt that they had a great need for something I could easily be – the teacher, aunt, distant relative, or older woman who is a very useful figure in young girl’s lives. (Paneth 2020; 61)

This allowed them to share confidences, and for Marie Paneth to share her personal interests.

She aims to foster democracy and cooperation

Maria Paneth is also clear about the political motivation of her work. Her goal in educational work, ‘was to make good, independent citizens for a good community’ (1944: 46). She was only too aware of the human costs of totalitarianism. Paneth had a strong belief in trying to work in a way that encouraged the children and young people to take responsibility and organize things for themselves. She was frustrated in this in various ways – and talks of her horror that “the children’s house” in Branch Street:

was changing from my original conception – a house run by the children from Branch Street according to their own ideas – into an imitation of a club, to be run like any other club, according to the ideas of grown-up people, and this before the children had so much as set foot on the doorstep.

Within youth work at the time, others were also arguing for clubs to be run by young people themselves and adopting ways of working that do not put themselves at the centre. Perhaps the most notable of these was Josephine Macalister Brew (1904 – 1957) who was also to write the first book on informal education:

Only by the slow and tactful method of inserting yourself unassumingly into the life of the club, not by talking to your club members, but by hanging about and learning from their conversation and occasionally, very occasionally, giving it that twist which leads it to your goal, is it possible to open up a new avenue of thought to them (1943: 16).

We can see that Marie Paneth could work similarly; to move from using one setting or approach to another; switching from moments when they are at the centre of activities to being at the periphery.

She looks to experience, conversation and reflection

Marie Paneth was keen to encourage situations where children and young people could experience new things and open new horizons to understanding:

… the fact that something new had entered their lives – something which, up till then, they never had the chance of experiencing – would, we hoped, make that change possible after all. (1944: 48)

One of the means she uses is going with children and young people to new places or relatively untried activities. However, she is an artist and is especially tuned into the potential of making art to the processes of developing an understanding of one’s feelings, relationships and thoughts.

One of the issues we have with Branch Street is that it is framed as a sociological analysis. As a result, we are provided with limited insight into the detailed processes of encouraging reflection and supporting the development of children and young people. There are glimpses here and there – such as her description of conversations about sex with young men and young women or the camping trip with a group of young women (1944: 16-28; 73-87). At face value it can seem what she does is set up situations e.g. for painting, and then work from the edge trying to help people hold boundaries and keep to the task. This may, in itself, be a helpful therapeutic or pedagogic activity. But from what Maria Paneth says, it is apparent that engagement with art media (and with many of the other activities) is generating material concerning emotional and social issues that are confusing and perhaps distressing. From time to time we get glimpses of her interventions, for example, talking with the children in the project about money being stolen from her purse; and encouraging young women to talk about their experience of the evacuation early in the war. Her account of her work with the Rock the Cradle group shows how she is encouraging reflection and learning. The group visits museums and galleries and Paneth encourages them to engage with what they see and experience. They explore different historical experiences at the British Museum, the readability of art at the National Gallery, and splitting the atom at the Science Museum.

She is self-reflective

Being able to respond to situations in the way that Paneth does entails the ability to reflect-in- and -on-action (Schön 1987). There is substantial evidence in Branch Street and Rock the Cradle of her ability to self-reflect and question her activities. We also know she insisted on the Branch Street project workers sharing and reflecting on their experiences.

Marie Paneth also questions the use of the whole project and the sensibilities that may have informed it:

Have we been intruders, disturbing an otherwise happy community, and is it the bourgeois in us, coming face to face with his opponents, who mind and wants to change them because he feels threatened? Or do they need help from outside?

At the end of Rock the Cradle Marie Paneth asks herself how much the young people she had been working with had benefitted directly from the teaching and how much from the personal contact and her readiness to give of her time. Some of the work was planned, but much was developed on the spur of the moment as situations arose. Paneth reported that she could not assess how much they would have advanced without these interventions. She is sure there could have been many ways of dealing with situations: ‘but all would have shown how little was necessary, as their goodwill unfolded in all its beauty. You have to experience it to believe how easily the innate strength of their sane nature turned towards life’ (Paneth 2020: 114). The thing about this is that such ‘unfolding’ requires relationship and sensitivity on the part of the educator – and this is what Marie Paneth was able to offer and what we need to cultivate.

Conclusion – on personality and stance

While we have explored some of the concerns lying behind Marie Paneth’s practice – and the sources of theory she appears to be drawing upon, we have not considered her personality. Nor have we looked particularly at her haltung or stance – and these are likely to have been central to how she was experienced.

First, personality. If we listen to Elizabeth Jane Howard, then it is obvious that she was a presence in a room – and engaging company. She described her as having a ‘kind of seductive liveliness, an inward amusement at anything we said’; being assured, and enjoying amazing and shocking people with her stories. She was ‘unusual and exotic’ (Howard 2002: 114). Thomas Ulrich, when he was a child, recognized her talent and experienced her as ‘difficult’ and ‘quite intimidating’. We also know that she had grit and determination when working in Branch Street. She appears to have been a ‘larger than life’ character. This, combined with her ability to think on her feet and a repertoire of theories and approaches, meant she must have been a formidable force. This can then be added to her talent as an artist. Her contemporary, Josephine Macalister Brew was similarly described. Their exoticness, enthusiasm and interests can be both engaging and threatening – and it is easy to understand some of the reactions to Paneth in Branch Street. On the other hand, for the children and young people they are working with, they can be exciting, insightful and life-changing.

Second, haltung. Within informal education and social pedagogy, there is an emphasis on the bearing and attitude of the worker. The German term for this is Haltung. It is also translated as stance, posture or mindset. Pedagogues act in the belief that, as Bertold Brecht put it some time ago, ‘When taking up a proper bearing, truth …will manifest itself.” (BBA 827/07, ca. 1930, in Steinweg 1975: 101).

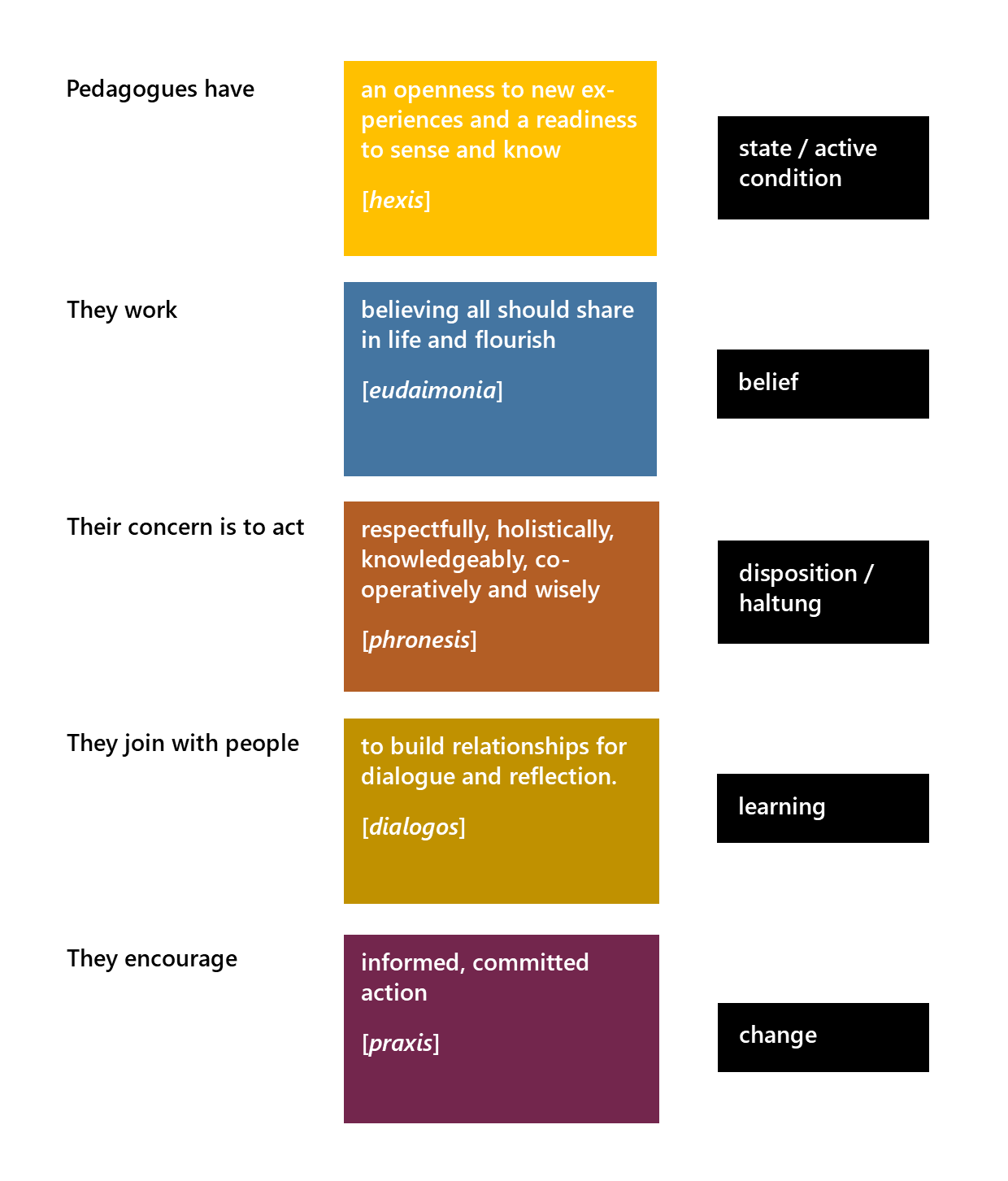

When looking at what pedagogues (and informal educators) do, we find – in Aristotle’s terms – a leading idea (eidos); what we are calling ‘haltung’ (phronesis – a moral disposition to act truly and rightly, and the ability to reflect upon, identify and decide on ends that cultivate flourishing); dialogue/interaction; and praxis (informed, committed action) (Carr and Kemmis 1986; Grundy 1987). To this, we need to add what Aristotle discusses as hexis – a readiness to sense and know. This is a state – or what Joe Sachs (2001) talks about as an ‘active condition’. In the following summary, we can see many of the elements we have been exploring here about Marie Paneth.

It is interesting to try and work out where Marie Paneth fits into all this. She was open to new experiences and had a readiness to sense and know. It is also clear that she shared the concern for the flourishing of all and had a stance or haltung that is close to the disposition described above. She also looked to build relationships, to encourage conversation and to stimulate thought and reflection. From accounts of Branch Street and the work undertaken with The Windemere children, there is evidence of change and development but the extent to which it could be described as praxis probably differs from intervention to intervention – and between Branch Street and Windemere, and then Rock the Cradle.

As stated at the outset, Marie Paneth was a talented painter, art therapist and pedagogue. Branch Street was a remarkable piece of work – and has to be seen as a great piece of reflective writing about practice. In the film The Windemere Children and the accompanying documentary, we can appreciate something of her impact as an art therapist and hopefully, this will bring her work to the attention of more pedagogues and therapists. Now, thanks to the publication of Rock the Cradle we can see the developments in her thinking and practice and confirmation of her importance as an educator.

Resources

Library of Congress: Marie Paneth Papers

Correspondence, a diary, writings, reports, notes, and children’s artwork chiefly documenting Paneth’s therapeutic use of art in working with children who suffered traumatic experiences. Subjects include Paneth’s book, Branch Street: a sociological study concerning her work with children during the bombardment of London, England, during World War II, her post-war work with children who survived German concentration camps, her years in Vienna, Austria, and Indonesia, her theories about drawing, and her art studies with Franz Cizik. Correspondents include Heinz Hartmann.

https://www.loc.gov/item/mm82058735/

References

Aichhorn, A. (1925/1951). Verwahrloste Jugend. Die Psychoanalyse in der Fürsorgeerziehung [Wayward youth. Psychoanalysis in care education]. Bern, Switzerland: Huber.

Aichhorn, A. (1972). Erziehungsberatung und Erziehungshilfe: 12 Vorträge über psychoanalytische Pädagogik. Aus dem Nachlass August Aichhorns [Educational counselling and educational support: 12 lectures about psychoanalytical pedagogy. From the inheritance of August Aichhorn]. Reinbek, Germany: Rowohlt.

Avery, T. (2020). The Windemere Project, talking in The Windemere Children. In their own words. (Producer Francis Welch), BBC 4. [https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000dt7g. Retrieved February 12, 2020]

Bernfeld, S. (1926/1971). Die psychologischen Grundlagen der Gefährdetenfürsorge [Psychological basics of care for people at risk]. In L. von Werder & R. Wolff, (Eds.), Antiautoritäre Erziehung und Psychoanalyse [Anti-authoritarian education and psychoanalysis] (pp. 275-278). Frankfurt am Main, Germany: März.

Bernfeld, S. (1929/1971). Der Soziale Ort und seine Bedeutung für Neurose, Verwahrlosung und Pädagogik [Social place and its meaning for neurosis, waywardness and education]. In L. von Werder & R. Wolff, (Eds.), Antiautoritäre Erziehung und Psychoanalyse [Antiauthoritarian education and psychoanalysis] (pp. 198–211). Frankfurt am Main, Germany : März.

Block, S. (Writer). (2020). The Windemere Children (Director Michael Samuels). First shown: January 27, 2020. IMDb details: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt10370380/

Brew, J. Macalister (1943). In The Service of Youth. A practical manual of work among adolescents. London: Faber.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research. Lewes: Falmer.

Freud, A. (1937). The ego and the mechanisms of defence. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, A. in collaboration with Dann, S. (1951). An experiment in group upbringing, The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 6:127-168. Reproduced in 1968 in The writings of Anna Freud. Volume IV Indications for Child Analysis and other papers 1945-1956. (New York: International Universities Press Inc.). The writings of Anna Freud can be borrowed from the Internet Library [https://archive.org/details/writingsofannafr0004freu/page/162/mode/2up]

Geni.com. Genealogy [https://www.geni.com/people/Marie-Paneth/6000000007470155807. Retrieved January 12, 2020].

Grundy, S. (1987). Curriculum. Product or praxis. Lewes: Falmer.

Gutteridge, M. V. (undated). The classes of Franz Cizek, The Free Library. [https://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+classes+of+Franz+Cizek.-a08934232. Retrieved: January 17, 2020]

Hartnell, M. (2020). ‘Lost Girls’ Artwork from the Holocaust, Library of Congress Blog January 15, 2020. [https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2020/01/lost-girls-artwork-from-the-holocaust/. Retrieved: January 18, 2020].

Hogan, S. (2001). Healing Arts: The history of art therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Howard, E. J. (2002). Slipstream. A memoir. London: Macmillan

Hothi, A. (2014). On the methodologies of the adaptation of text for gallery exhibition. MPhil by thesis, Critical Writing in Art & Design, Royal College of Art, London. [http://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/1680/1/AH_thesis270115.pdf. Retrieved January 14, 2020].

Isbister, J. N. (1985). Freud, an introduction to his life and work. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Jeffs, T. (2003). Classic texts revisited – Branch Street by Marie Paneth. Youth & Policy 81. [https://www.youthandpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/y-and-p-81.pdf. Retrieved January 14, 2020].

Koslovsky, R.: The Junk Playground. Creative destruction as an antidote to delinquency. Paper presented at the Threat and Youth Conference, Teachers College, April 1, 2006. [http://threatnyouth.pbworks.com/f/Junk%20Playgrounds-Roy%20Kozlovsky.pdf. Retrieved: January 16, 2020]

Koslovsky, R. (2007). Adventure Playgrounds and Post-war Reconstruction in Gutman, M./de Coning-Smith, N. (Hg.): Designing modern childhoods: History, Space and Material Culture of Children: An International Reader. Rutgers.

Korotin, I and Stupnicki, N. (2018). Biografien bedeutender österreichischer Wissenschafterinnen. Die Neugier treibt mich, Fragen zu stellen. Wien – Köln – Weimar: Böhlau Verlag. [https://austria-forum.org/web-books/biografienosterreich00de2018isds/000667. Retrieved January 12, 2020].

McAleer, M. (2010). Marie Paneth Papers. A Finding Aid to the Papers in the Sigmund Freud Collection in the Library of

Congress. Washington DC: Library of Congress.

Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) (1948a). Art Work by Children of Other Countries. Exhibition Record [https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3236?. Retrieved December 19, 2019].

Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) (1948b). Concentration camp children’s art from Europe to be compared with the work of D.P. children, in America. Press Release. New York: MOMA. [https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_325598.pdf. Retrieved: January 14, 2020].

The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 396 WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards 1939-1947; Reference Number: HO 396/67 [Retrieved May 28, 2020]. [NB there are two cards with the same reference – one for the appeal, another detailing the exemption].

Paneth, M. (1944). Branch Street. A sociological study. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Paneth, M. (1946). Rebuild those lives, Free World, April 1946. [https://www.unz.com/print/FreeWorld-1946apr-00053/. Retrieved January 15, 2020].

Paneth, M. (1955). Marie Paneth. Catalog of an exhibition held Mar. 9-22, 1955. New York: Van Diemen-Lilienfeld Galleries. [https://www.worldcat.org/title/marie-paneth/oclc/77739556&referer=brief_results. Retrieved: September 16, 2020].

Paneth, M. (1956). Paneth. Catalog of an exhibition held Mar. 9-22, 1956 [in French]. Paris: Galerie Marcel Bernheim. [https://www.worldcat.org/title/paneth/oclc/78844321&referer=brief_results. Retrieved: September 16, 2020].

Paneth, M. (1958). Paintings by Marie Paneth. New York: Condon Riley Gallery, inc. [https://www.worldcat.org/title/paintings-by-marie-paneth/oclc/79951340&referer=brief_results. Retrieved: September 16, 2020].

Paneth, M. (1963). Maria Paneth Exhibition Catalogue – January 15-February 2, 1963. New York : Gallery 63. [https://www.worldcat.org/title/marie-paneth/oclc/11382807&referer=brief_results. Retrieved September 16, 2020]

Paneth, M. (2020). Rock the Cradle. Fallowfield, Manchester: 2nd Generation Publishing.

Russell, C. E. B. and Rigby, L. M. (1908) Working Lads’ Clubs, London: Macmillan and Co.

Schön, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. How professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith.

Smith, M. K. (1999-2019) ‘Social pedagogy’ in The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, [https://infed.org/mobi/social-pedagogy-the-development-of-theory-and-practice/. Retrieved: January 16, 2020].

Smith, Mark K. (2006). George Goetschius, community development and detached youth work, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/george-goetschius-community-development-and-detached-youth-work/. Retrieved: December 22, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2007a, 2020). M. Joan Tash, youth work, and the development of professional supervision, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/m-joan-tash-youth-work-and-the-development-of-professional-supervision/. Retrieved: April 8, 2024].

Smith, M. K. (2007b) ‘Classic studies in informal education – Working with unattached youth’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/classic-studies-working-with-unattached-youth/. Retrieved: December 22, 2019].

Spinley, B. M. (1953). The Deprived and the Privileged. Personality development in English society. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Stanley, M. (1878). Work About the Five Dials. London: Macmillan and Co. See extract in the archives.

Stanley, M. (1890). Clubs for Working Girls. London: Macmillan. (Reprinted in F. Booton (ed.) (1985) Studies in Social Education 1860-1890, Hove: Benfield Press.

Starkey, P. (2000). Families and Social Workers. The Work of Family Service Units 1940-1985. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Steinweg, Reiner, ed. (1976). Brecht’s Modell der Lehrstücke. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Titmuss, R. M. (1950). Problems of Social Policy. London: HMSO and Longmans.

Ulrich, T. (2018). Correspondence with the writer.

Viola, W. (1936). Child Art and Franz Cizek. Vienna: Austrian Junior Red Cross | New York: Reynal and Hitchcock. [https://another-roadmap.net/articles/0002/8598/viola-cizek-textteil.pdf. Retrieved January 16, 2020]

Welshman, J. (2004). The Unknown Titmuss, Journal of Social Policy, 33, pp225-247 DOI:10.1017/S0047279403007475. [https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/19952/1/S0047279403007475a.pdf. Retrieved January 14, 2020].

Weininger, S. S. (2020). Society of Independent Artists [SIA], Oxford Art Online/Grove Art Online. [https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T079485. Retrieved January 15, 2020].

Wills, W. D. (1941). The Hawkspur Experiment. An informal account of the training of wayward adolescence. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Wills, W. D. (1945). The Barns Experiment. [An account of the organization of a hostel for boys in Peebleshire. With plates.] London: George Allen and Unwin.

Winnicott, D. W. (1959). Obituary: Oscar Friedman in L. Caldwell and H. T. Robinson (eds.). The Collected Works of D. W. Winnicott: Volume 5, 1955-1959. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

World Jewish Relief (2020). The Boys. World Jewish Relief. [https://www.worldjewishrelief.org/about-us/the-boys. Retrieved: January 17, 2020]

Yivo Institute (undated). The Yivo Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. [https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Jeitteles_Family. Retrieved January 12, 2020].

Acknowledgements: My thanks to Tom Ulrich who provided important biographical details – Marie Paneth was his aunt.

Image: A group of boys set to work creating an allotment on a bomb site in London in 1942. Imperial War Museum IWM Non-Commercial Licence.

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2024). Marie Paneth – Branch Street, The Windemere Children and art therapy and pedagogy. The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/marie-paneth-branch-street-the-windemere-children-art-and-pedagogy/ . Retrieved: insert date].

Note: Parts of this article (especially on Branch Street) first appeared in 1996. A revised version was published in 2020 based on further research (a lot more material was available), and information provided by Tom Ulrich. Details of addresses and travel from 1939 onwards came largely from passenger arrival databases and probate information. In writing this I have not been able to access Marie Paneth’s papers in the Library of Congress which, I am sure, would spread considerable light on some important elements discussed here. However, a key manuscript – Rocking the Cradle – has been published (Paneth 2020) and I have used it to make further revisions. MKS (April 2024).

© Mark K. Smith 2024

The Juvenile Art Class is not a school, it is a work centre to which the children come of their own free will and where they can work just as their talents and inclinations prompt them. My educational task consists in furthering the creative giving of form and preventing imitation and copying. A drawing or any other product of a child is good, if the work accomplished accords with the child’s age and is altogether uniform in quality and when it is honest and true in every single detail.

The Juvenile Art Class is not a school, it is a work centre to which the children come of their own free will and where they can work just as their talents and inclinations prompt them. My educational task consists in furthering the creative giving of form and preventing imitation and copying. A drawing or any other product of a child is good, if the work accomplished accords with the child’s age and is altogether uniform in quality and when it is honest and true in every single detail.