new & updated

Maude Stanley, girls’ clubs and district visiting. Maude Stanley was one of the central pioneers of girls’ work and neighbourhood work in general. She produced an early and influential youth work text, and a fascinating exploration of work happening in the highly deprived Five Dials area of London. Maude Standley also helped found the London Union of Girls Clubs. (Updated January 2026).

Walking informal education – exploring developments in central London. Walking in central London, we can find many places associated with key figures and moments in the making of informal education. Explore them through a virtual (or real) walk based on Charles Booth’s famous poverty map. (Updated January 2026).

What is pedagogy? A definition and discussion. Pedagogy is often, wrongly, seen as ‘the art and science of teaching’. Mark K. Smith explores the origins and development of pedagogy and finds a different story – accompanying people on their journeys. Teaching is just one part of what they do. [Updated October 2025].

Josephine Macalister Brew, youth work and informal education. One of the most ‘able, wise and sympathetic educationalists of her generation’, Josephine Macalister Brew made a profound contribution to the development of thinking about, and practice of, youth work and informal education. [Updated September 2025]

featured

Education in Robert Owen’s new society: the New Lanark institute and schools. Robert Owen’s educational venture at New Lanark helped to pioneer infant schools and was an early example of what we now recognise as community schooling. Yet education was only a single facet of a more powerful social gospel which already preached community building on the New Lanark model as a solution to contemporary evils in the wider world. Ian Donnachie investigates.

Ivan Illich on deschooling, conviviality, and systems. Possibilities for education and social change. Known for his critique of modernisation and the corrupting impact of institutions, Ivan Illich’s concern with deschooling, learning webs and the disabling effect of professions struck a chord among many educators and pedagogues. We explore some key aspects of his theories and his continuing relevance for teaching, pedagogy and learning. [Updated and extended January 2025]

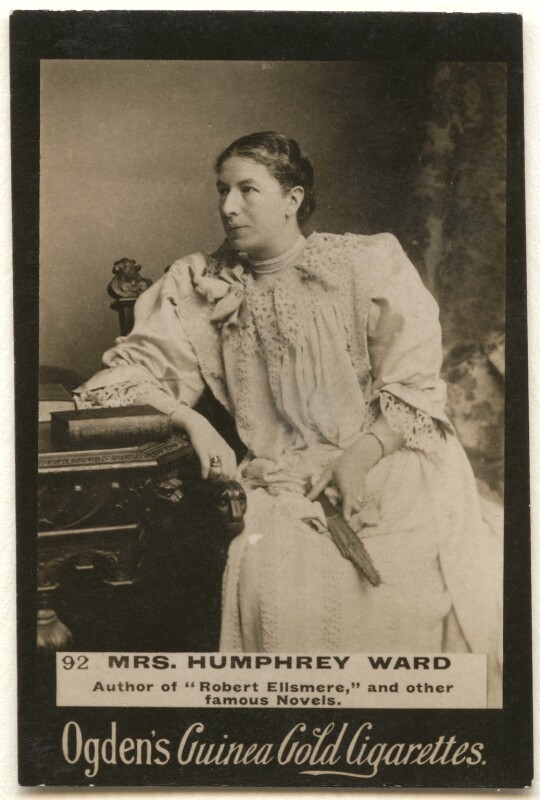

Mary Augusta Ward | Mrs Humphry Ward and the Passmore Edwards Settlement. Mary Ward, aka Mrs Humphry Ward, was one of the best-known writers of her day. She was also a key pioneer in the settlement movement and the development of provisions for children with disabilities and for play. Alongside this, Mary Ward was an advocate for the rights of women, yet she opposed the extension of the right to vote to them. We explore her life and contribution, and the settlement she founded. [updated November 2025]

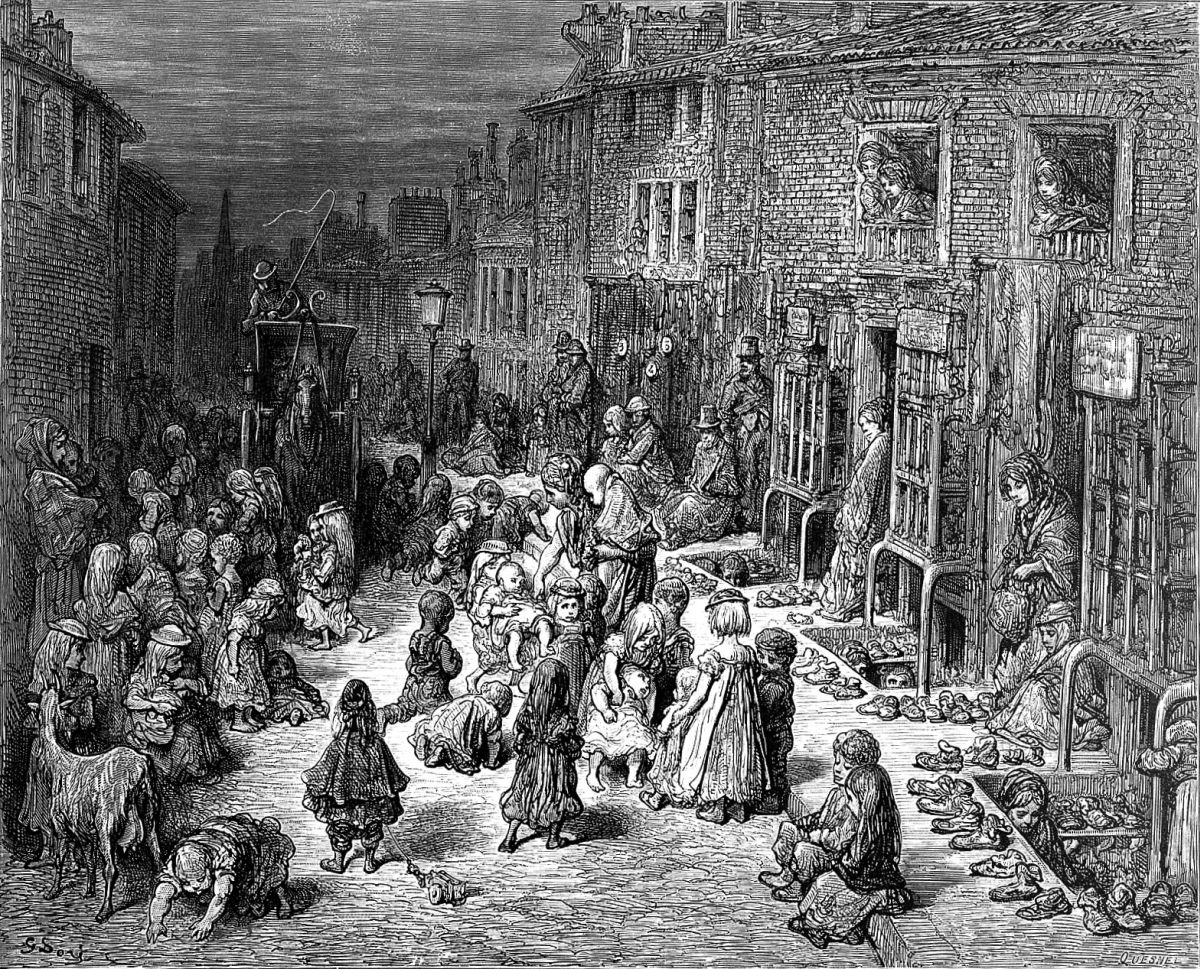

Our opening picture, Dudley Street, Seven Dials, London, by Gustave Doré. Wellcome Commons ccbya licence. It was one of the areas that Mary Ward worked in.

updated: January 24, 2026