James (Jimmy) Butterworth, Christian youth work and Clubland. The Rev. James Butterworth (1897-1977) made a very significant contribution to thinking and practice around youth work in the church. He pioneered a more youth-oriented approach within the Methodist Church and established a lasting Christian institution – Clubland – in Walworth, London.

contents: introduction · james butterworth – early life · walworth and clubland · james butterworth – his contribution to christian youth work · conclusion · further reading and references · links · how to cite this article

James Butterworth – early life

Jimmy Butterworth was the eldest of a family of five children living in Oswaldtwistle near Accrington, Lancashire. Born in 1897, he did well at school – but had to leave, aged twelve, when his father died (Poor Law regulations required that he had to contribute to the family income). He worked a ten-hour day in a dye works (enduring some pretty nasty conditions and earning just 3s a week) and then, in the evenings he sold newspapers or served in an eating-house. Jimmy Butterworth resented having to leave school and envied those boys who had been able to stay on and complete their grammar school education. His experience led him to the strong belief that young people, however, poor their circumstances, needed a place where they could go in the evenings for friendship, recreation and education (Eagar 1953: 374).

When his sisters were old enough to work he was able to return to education (at a local night school) and soon became known locally as ‘the boy preacher’.

Like many Lancashire lads stunted by premature employment and thirsting for self-expression, he might have trodden the worn road from preaching to politics, but the First World War broke out and he became Private Butterworth, James, in the Bantom Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers. The intimate knowledge of other men fostered by Army life gave him further instances of frustration, and he formed a conviction that the waste of boyish powers and the perversion of boyish ambitions were wicked things which should be corrected by the churches, for they alone, as far as he knew, had a mission to secure social justice. (Eagar 1953: 374-5)

Through army chaplains, James (Jimmy) Butterworth was able to gain admission in 1919 to Didsbury Theological College to train for the Methodist ministry. He did not have an easy time, having very particular ideas about his ministry and the role of the church. He was allowed to take over a derelict mission on the edge of Manchester where he soon became known as ‘the wee parson’ (he was of very slight build – just five foot tall) and began to develop work with local working boys. However, the College was approached by a group to help them to find someone to take over a run-down church in Walworth, London. It seemed that James Butterworth fitted the bill.

Walworth and Clubland

When James (Jimmy) Butterworth came to the Walworth church in 1922 there were just 25 people in the congregation. A Wesleyan Methodist Church had been on site since 1813 and amongst its famous former attendees (during the 1850s) was William Booth (the founder of The Salvation Army). However, most of the congregation some seventy years later came to the Sunday services from the suburbs to which they had migrated. While loyal, they were something of an anachronism – their church had become an ‘alien institution’:

Around it had been compacted a muddle of mean streets, bestridden by railway arches and coal-sidings, in which a miscellany of small factories, crammed into the former garden space of houses, built for single families but ‘made down’ without structural alterations for several, smoked, smelt and were noisy. Children, adolescents and adults alike ignored the grimy chapel, which ignored them. (Eagar 1953: 376)

It was a situation that appalled James Butterworth. The only direct knowledge he had of the area before he arrived was his contact with ‘Patrick’ – a reformatory schoolboy he had met in Manchester. Butterworth sought him out – and found that he had both returned to Walworth and to criminal activity (in part to escape the sordid conditions he had come back to). ‘Patrick’ ended up in prison – and his situation confirmed and quickened James Butterworth’s desire to focus his ministry on work with local young people. He told the congregation that there were Methodist churches in the places where they lived – and that they should worship there.

James (Jimmy) Butterworth then set out to reach young people who would not normally be attracted to the church. His youth work approach involved four particular elements:

Young people deserved good quality facilities. Their activities and clubs should be housed in attractive buildings that were both functional and beautiful. They also deserved the best equipment. Why are these things less necessary for those who live in the slums of south London, he asked, than for university undergraduates? (Morgan 1939: 285)

There should be a strong emphasis on participation and involvement in the governance of the club or group. Clubland had large separate clubs for boys and girls and older members organized on ‘a specially thought-out system of self-government (club parliament. separate ‘houses’ run by selected members from each section) (Rooff 1935: 182).

Members should make an adequate contribution to the cost of the facility.

All members should take their part in the life of the church. ‘Church loyalty’ and ‘all-round fitness’ were central aims.

Butterworth’s focus on young people necessarily meant that there was significantly less emphasis on work with other ages – and this was a bone of contention within the Methodist Church. His emphasis on parliamentary-style ‘government’ and large clubs had some parallels in the boys’ clubs championed by Charles Russell (Russell and Rigby 1908) and later by Basil Henriques (1933). In many ways, the set up in this, and the other examples, would better be described as involving a measure of self-government. Both Basil Henriques and Jimmy Butterworth, for example, were major presences in their organization – and the process is a slow one (they were also friends). Initially, the leader has to take responsibility, then gradually hand over work to a committee initially selected by the leader and helpers. Then elections might be possible (Henriques 1933: 79-93). James (Jimmy) Butterworth urged club workers to be patient and to persevere with the encouragement of self-government – especially in the face of setbacks. He argued from his experience that members ‘soon discover for themselves that legislation by the proper procedure is a thrilling way to govern’ (1932). ‘They find it sensible’, he continued, ‘to listen whilst others talk and are not likely to have the whole thing spoiled by a few foolish members out for a lark or allow a rowdy element to turn it into a pantomime’. While he does appear to have genuinely sought to take things further down the road of self-government than many boys’ clubs workers, he inevitably remained a central reference point.

James (Jimmy) Butterworth wanted to build a complex of buildings for young people and, after some years of fundraising, he was able to demolish the old church in the mid-1930s and build Clubland. It consisted of club rooms, workshops, an art room, a church, a theatre, a gymnasium, a hostel, an open-air playground (on the roof) and a residence for the Head a building for girls and boys clubs and was designed by Sir Edward Maufe (the architect of Guildford Cathedral). It was opened in 1939 by Queen Mary, (who was the patron of Clubland for several years). In many respects, James (Jimmy) Butterworth had taken a leaf out of Henry Morris‘ book. Morris had also insisted on the importance of good architecture and convivial surroundings. A. E. Morgan (1939) singled out Clubland for special comment. ‘Clubland’, he asserted, ‘has achieved the impossible’. Sadly, the new church and several of the clubrooms were destroyed just two years later by a bomb during an air raid. Work was able to continue in some of the lower club rooms and at the end of the war renovation work began. The new building was finally opened in 1964.

In the late 1960s, the work of Clubland had to be rethought. Much of the area it served was cleared – and rebuilt as the Aylesbury Estate (it was the largest public housing estate in Europe and is again now subject to major redevelopment). According to Frost (2006: 67), the housing clearance meant the loss of 300 members and 30 out of the 36 officers. At the same time, the way of working used by Jimmy Butterworth – with its emphasis on club life and more formal activities – was no longer fashionable or necessarily attractive to large numbers of young people. There were several factors also at play here (see our discussion of youth work) and the situation rather depressed Jimmy Butterworth (see Loyalty and Service, a short film on his work).

Much of the work was only made possible by Jimmy Butterworth’s abilities as a fund-raiser. He was able to network and communicate the vision underpinning the work – the desperate needs locally, and the unique contribution that Clubland could make. He gained the support of notable celebrities such as Bob Hope (who was originally from south London), John Mills, Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. He was also supported by Lord Rank and the Joseph Rank Benevolent Trust (who were great funders of Methodist building projects) (see Frost 2006). Butterworth himself became something of a celebrity (appearing for example on This is Your Life in 1955) (Frost 2006: 65-6).

James Butterworth’s contribution to Christian youth work

Leonard Barnett makes the following assessment of Butterworth’s contribution:

For years he spoke bluntly to his own Church, neither giving quarter nor desiring it. Like most men of his calibre, he had to stand a great deal of misunderstanding and acrimony from those who refused to face the facts, or were unable or unwilling to do anything about them in the way he passionately pleaded for. If he was for long the stormy petrel of Methodist youth work, he was undoubtedly the one to set at length many others winging in the same adventurous and essentially Christian direction. (Barnett 1951: 58)

Barnett goes on to make two key points about the work undertaken at Clubland. First, it was not a pattern that could (or should) be picked up by many local churches. ‘In its largely youthful membership, it tends toward a denial of the true family nature of the Church, and towards creating a kind of “club Christianity” which in the long run does not ideally serve the interests of the Kingdom of God’ (op. cit.). This was a judgement echoed by Bryan Reed, another important figure in the development of Methodist youth work. ‘Will young people reared in youth centres’, he asked, ‘afterwards settle down in ordinary churches? (quoted by Frost 2006: 67).

Second, while the pattern of work that emerged ran against that which in an ideal world was desirable, it was what emerged out of that particular environment. ‘It must always be the Christian’s task, Barnett (1951: 58) comments, ‘to do the thing that is nearest, to the best of his ability, rather than wait until all the omens and circumstances are favourable’.

A further, important, consideration is the extent to which the success of Clubland depended upon the personality of James (Jimmy) Butterworth – and the relative uniqueness of what it offered. Butterworth’s personality – and his ability to attract high profile supporters was not easy to follow nor to emulate (Frost 2006: 67). Further, the more centres there were that looked like Clubland – the less ‘special’ they appear to funders.

Conclusion

The crusading spirit of James Butterworth and Clubland was of ‘enduring and universal value’ (Barnett 1951: 59). His writing and people’s direct experience of the work was to influence a significant number of people both within the Methodist church and beyond. The quality of the facilities he developed was an obvious example to others; his emphasis on self-government an important focus. But it was his calls for the Church to focus more strongly on the needs of young people – especially in areas where there was significant deprivation that commanded attention – and helped create the right environment for the establishment of the Methodist Association of Youth Clubs and the massive expansion of youth club work within Methodism during the Second World War and after.

Today Clubland is part of the Walworth Methodist Church which has the largest Methodist congregation in London with 450 members and its average weekly attendance for worship is 350. 95 per cent of the membership is black – with the largest number coming from West African families (walworthmethodist.org.uk). Youth work remains, but there is also a full community programme operating within the building with over 50 voluntary groups regularly using the premises. These include clubs for those with special needs (the Freddie Mills Club), for ethnic minorities (including a Turkish Luncheon Club, an African Caribbean Luncheon Club and classes for those with English as a second language) and young people (Clubland Methodist Young Adults and Southwark’s Black Mentor Scheme) (details from the Walworth Methodist website). Clubland also joined with the West London Mission to run a 34-bed Hostel (for overseas students and asylum seekers) (using the hostel building that Butterworth built). West London Mission’s Big Hour project also has 10 flats for a rough sleepers initiative. Southwark Carers (who also offer a range of counselling services) are also based in the building now.

Further reading and references

Butterworth, John and Waine, Jenny (2020). The Temple of Youth. Jimmy Butterworth and Clubland. London: JL Club Press. This book is the first complete biography of the Reverend James Butterworth (1897-1977) and authoritative history of Clubland. Click for details. [John Butterworth is Jimmy Butterworth’s son].

References

Barnett, L. P. (1951) The Church Youth Club, London: Methodist Youth Department.

Butterworth, J. (1925). Byways in Boyland. London: Epworth Press

Butterworth, J. (1927) Adventures in Boyland. Pages from a boys’ club scrapbook. London: Epworth Press.

Butterworth, Jimmy (1932) Clubland, London: Epworth Press.

Butterworth, John and Waine, Jenny (2020). The Temple of Youth. Jimmy Butterworth and Clubland. London: JL Club Press.

Dawes, F. (1975) A Cry from the Streets. The boys’ club movement in Britain from the 1850s to the present day, Hove: Wayland Press.

Eagar, W. McG. (1953) Making Men. The history of boys’ clubs and related movements in Great Britain, London: London University Press.

Ette, G. (1946) For Youth Only, London: Faber and Faber.

Frost, B. with S. (2006) Pioneers of Social Passion. London’s cosmopolitan Methodism. Peterborough:

Henriques, Basil L. Q. (1933) Club Leadership, London: Oxford University Press. (2e 1934; 3e 1942)

Morgan, A. E. (1939) The Needs of Youth. A report made to King George’s Jubilee Trust Fund, London: Oxford University Press.

Rooff, M. (1935) Youth and Leisure. A survey of girls’ organizations in England and Wales, Edinburgh: Carnegie United Kingdom Trust.

Russell, C. E. B. and Rigby, L. M. (1908) Working Lads’ Clubs, London: Macmillan and Co.

Links

JB-Clubland – The official Clubland website, funded from the JB Memorial Trust and maintained by a team of family and ex-members. Its purpose is to provide an archive for social historians and any other interested visitors and invites those who remember Clubland to contribute thoughts, photographs, letters, etc., or just to contact old friends. https://jb-clubland.co.uk/

Rev. Jimmy Butterworth and the activities of Clubland. You can view several silent different films – some colour, some black and white – shot over several years of Clubland. (British Film Institute).

See, also, a short film – Loyalty and Service – reflecting on Jimmy Butterworth’s achievements [https://www.londonsscreenarchives.org.uk/title/3357/]

Clubland: the Walworth Methodist Church page gives a flavour of the work today.

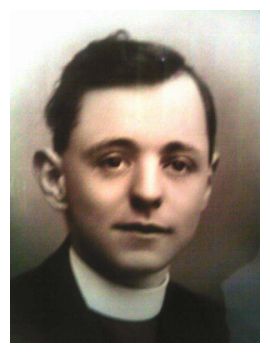

Acknowledgement: The picture of James (Jimmy) Butterworth was kindly provided by Wandsworth Methodist Church. The picture of Clubland, Wandsworth – infed.org.

To cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2002-2020) ‘James Butterworth, Christian youth work and Clubland”, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/james-butterworth-christian-youth-work-and-clubland/ Retrieved: enter date].

© Mark K. Smith 2002, 2009, 2020