Mary Augusta Ward aka Mrs Humphry Ward was one of the best-known writers of her day. She was also a key pioneer in the settlement movement and the development of provision for children with disabilities and for play. Alongside this Mary was an advocate for the rights of women, yet she opposed the extension of the right to vote to them. We explore her life and contribution, and the settlement she founded.

Opening picture: Passmore Edwards Settlement (now Mary Ward House) by Charles S. Olcott, Public domain sourced via Wikimedia Commons.

contents: introduction | developments | suffage | The First World War | final days | bibliography

_________

Mary Augusta Ward (1851 -1920) was a granddaughter of Dr Thomas Arnold of Rugby and a niece of Matthew Arnold. Born in Hobart, Tasmania, her father was a professor of literature and later an inspector of schools. The family returned to the UK in 1856. Mary Arnold was sent to boarding school and spent much of her time with her grandmother (her father was teaching in Dublin). When her father gained an appointment as a lecturer in history at Oxford, Mary was able to return to the family. In 1872, she married Thomas Humphry Ward, a fellow and tutor at Brasenose College (and a member of the staff of The Times) and was subsequently known as Mrs Humphry Ward (Thomas generally wrote as Humphry Ward). Within a couple of years, she was to have her first child – Dorothy Mary and then in 1876 her son Arnold Sandwith. In 1879, her final child – Janet Penrose – was born (Sutherland 1991: 58-9).

She developed her activities as a writer and was also central to efforts to open up Oxford University to female students. One element of this was participation in the campaign to found Somerville College – and to name it after Mary Somerville (1780-1872) – the Scottish scientist and polymath. Mary Humphry Ward went on to become Secretary to Somerville College Oxford (1879-1881) before moving to London. She lived at 61 Russell Square during much of the 1880s (on a site now covered by the Imperial Hotel).

Mary Ward was becoming heavily engaged as a writer. She contributed to the monthly Macmillan’s Magazine and started work on a children’s book – Milly and Olly – that was published in 1881 [this and a significant number of her other works are available from Project Gutenberg). She was to write a further 27 novels. A number had romantic/spiritual themes. An early example, Robert Elsmere (1888) caused some controversy and centred around a ‘modern priest who could no longer believe in miracles who founded a sect in the East End which preached a melange of Christianity, Positivism and the social gospel’ (Briggs and Macartney 1984: 10).

Mary Ward was becoming heavily engaged as a writer. She contributed to the monthly Macmillan’s Magazine and started work on a children’s book – Milly and Olly – that was published in 1881 [this and a significant number of her other works are available from Project Gutenberg). She was to write a further 27 novels. A number had romantic/spiritual themes. An early example, Robert Elsmere (1888) caused some controversy and centred around a ‘modern priest who could no longer believe in miracles who founded a sect in the East End which preached a melange of Christianity, Positivism and the social gospel’ (Briggs and Macartney 1984: 10).

In 1892, the Humphry Wards moved into Stocks Manor House – a substantial Georgian mansion close to Aldbury, Hertfordshire. Built in 1773, it was to become a popular weekend destination for writers and thinkers. One of its minor claims to fame is that it features on the cover of the Oasis album Be Here Now. However, there was still a great deal for the Wards to do in London. As a result, they also kept a ‘house in town’ in Grosvenor Place rather than spending time travelling by rail from Tring Station (about 2 miles from Stocks) (Sutherland 1991: 133).

The success of Robert Elsmere – and Ward’s interest in the establishment and work of the Toynbee Hall in 1884 – appear to have led her to seek to establish a similar (but largely Unitarian) settlement. The original settlement began as University Hall Settlement in rented premises in Gordon Square in 1890. The stated aim was to provide ‘improved popular teaching of the Bible and of the history of religion’, and to secure for residents of the Hall ‘opportunities for religious and social work’ (quoted by Katharine Short, undated). Ward had adopted the standard settlement model of providing accommodation in exchange for work with local people. Soon the Marchmont Hall on Marchmont Street was also used for various clubs, lectures and small concerts. John Passmore Edwards – who financed many philanthropic efforts in London – offered to fund a new building – and this opened in 1897 as the Passmore Edwards Settlement at 9 Tavistock Place WC1. Designed by A. Dunbar Smith and Cecil Brewer, (who were also residents of University Hall Settlement), the building was distinctly art-nouveau in style – as can be seen by the opening photograph. It has now become a Grade One Listed Building.

Developments

The settlement, like Toynbee Hall, had been initially aimed at professional young men who committed to giving significant time to its work. However, this changed in 1915. It became a Women’s Settlement headed by a former Vice Principal of King’s College for Women – Hilda Oakeley (1867-1950). Oakeley retained a part-time lectureship in philosophy at King’s and was later to return there as a reader in 1921 (Oakeley 1938). It became the base for several interesting developments and innovations. Two in particular stand out.

First, Mary Ward was a strong advocate of the enhancement of schooling for children with disabilities. As a result, the settlement housed the first fully equipped classrooms for children with disabilities living in the community. The model school opened its doors in 1898 and received funding (rate aid) from the London School Board the following year. It provided coursework, physical therapy and meals (Young and Ashton 1956: 203). The quality of the results was later used to pressure the London County Council into establishing similar schools (Vicinus 1985: 234-5).

A second, crucial, innovation was the development of a play centre for children. Mary Neal had begun a Saturday ‘playroom’ for children in Marchmont Hall. Mary Ward realized that there was considerable potential in the work. With the opening of the new centre, considerable effort was put into developing the work. By 1902 over 1200 children were coming to sessions (the most the building could hold) (Sutherland 1991: 225). The centre provided a place of warmth and safety; the opportunity to help children to develop their play; and the opportunity for comradeship and play in common in a situation where people have an equal chance and where bullying could be contained. (This was how Mary Ward herself described the qualities of a play centre in the prefatory note to her daughter Janet’s discussion of the first 25 years of play centre work: Trevelyan 1920). It is a testament to Ward’s ability to lobby and to publicise that there was a major expansion of play centres in London (attendance at play centres in London totalled 1.7 million in 1918/19).

Renamed in 1921 following Mary Humphry Ward’s death, Mary Ward House’s role as a women’s settlement continued. There was a focus on social work during the 1930s and 1940s. An advice centre was established in the 1940s to provide both legal and financial advice to those with low incomes. They also went on to set up and host clubs for unemployed men; a Dramatic Arts Centre and musical concerts; and adult education classes including formal courses, lectures and debates (Short, undated). However, Mary Ward House also faced significant financial problems and needed to respond to the gentrification of the area. As a result, there were discussions about relocating to a poorer neighbourhood – but for various reasons, this did not happen. The decision was thus made to share the building – and they were joined in the early 1960s by the National Institute for Social Work (Sutherland 1990).

The work continued and in the 1970’s the name of the organization changed to the Mary Ward Centre. There had been a shift in focus towards adult education (and some community outreach work). From 1982 it was based at 42 Queen Square WC1 (by Great Ormond Street). The Centre then moved in 2023 to Stratford [275-285 Queensway House, High Street, London, E15 2TF]. The Mary Ward Centre also merged with another former women’s settlement based in Southwark – Blackfriars. Mary Ward House, following the demise of the National Institute for Social Work, is today used as a conference and exhibition centre.

Suffrage

Whilst Mary Augusta Ward was a campaigner for women’s rights, and concerned with the needs of children and families, she was anti-suffrage. Indeed, she became the first President of the Anti-Sufferage League in 1908. She wrote extensively about her position and her belief that major political decisions should be taken by men. She helped to establish and went on to edit the Anti-Sufferage Review and was critical of the activities of Suffragettes (particularly in two novels – The Testing of Diana Mallory [1908] and Delia Blanchflower [1914]). A number of the people she had worked with – such as Mary Neal and Emmeline Pethick Lawrence were not just on the other side of the fence but at the centre of the Suffragette Movement. Significantly, her youngest daughter Janet was a Suffragist. She was ‘devoted to her mother, while at the same time expressing an ineradicable scorn and hatred for her mother’s set’ (Sutherland 1991: 251).

In 1904 Janet married George Macaulay Trevelyan – who had just resigned as a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge to write full-time. He went on to become ‘the most famous, the most honoured, the most influential and the most widely read historian of his generation’ (Cannadine 1992). Mrs Humphry Ward was ‘displeased when her daughter took up with a man “so wholly non-Christian”, who “looks forward to a civil marriage” but Janet and George were her match and insisted on a registry office wedding. Janet had been home-educated, but was, according to David Cannadine (1992: 10; see, also Cannadine 2007), renowned for ‘the force of her intellect and the independence of her spirit’. She had already translated both Adolf Jülicher’s Introduction to the New Testament and Wilhelm Bousset’s Life of Jesus and went on to write several books including a history of Italy. As we have already seen, she also became involved in, and wrote about, the development of play centres and later authored a biography of her mother (1923). George and Janet were to have a daughter – Mary Caroline (born in 1905), and two sons Theodore Macaulay (born in 1906 but sadly died aged four and a half in 1911) and Charles Humphry in 1909. The Bournemouth Daily Echo reported that Theodore Macauley had died at Swanage ‘under an operation for appendicitis. Mrs Trevelyan had only just herself recovered from a similar operation, and the family were at Swanage for her health’ (April 28, 1911).

The First World War

Close on the heels of the last of her anti-sufferage books, Mary Ward began to write about the First World War. This was at the request of Theodore Roosevelt. He wanted her to explain why it was happening – and why it needed supporting. The result was three short books aimed largely at a USA readership: The War on All Fronts – England’s Effort (1916), Towards the Goal (1917), and Fields of Victory (1919). In the first of these, she explains in her introduction:

I have been allowed to go, through the snow-storms of this bitter winter, to the far north and visit the Fleet, in those distant waters where it keeps guard night and day over England. I have spent some weeks in the Midlands and the north watching the vast new activity of the Ministry of Munitions throughout the country; and finally in a motor tour of some five hundred miles through the zone of the English armies in France, I have been a spectator not only of that marvellous organisation in northwestern France, of supplies, reinforcements, training camps and hospitals, which England has built up in the course of eighteen months behind her fighting line, but I have been—on the first of two days—within less than a mile of the fighting line itself, and on a second day, from a Flemish hill—with a gas helmet close at hand! I have been able to watch a German counter attack, after a successful English advance, and have seen the guns flashing from the English lines, and the shell-bursts on the German trenches along the Messines ridge; while in the far distance, a black and jagged ghost, the tower of the Cloth Hall of Ypres broke fitfully through the mists—bearing mute witness before God and man.

The books sold well – both in the UK and the USA – and were translated into several languages. England’s Effort was, according to John Sutherland (1991: 354), a ‘shrewd mixture of eye-witness reportage, statistical bombardment, telling anecdote, and ‘beastly Hun’ propaganda’. He continues, ‘Odious as her war-mongering seems to later readers, England’s Effort was extremely well done. Propaganda is judged by results and Mary Ward’s book certainly got results’.

The final days

Mary Ward’s writing gained a wide readership – and generated a significant income which allowed the ‘two-house’ lifestyle and Humphry’s somewhat speculative expenditure on paintings etc. It could also be said to have, to some extent, allowed their son to enter Parliament as an MP, and amass serious gambling debts and a drinking habit. Her eldest daughter Dorothy never married and effectively became her mother’s companion and assistant – and manager of the house at Stocks. In addition, working together with Mary Ward’s secretary Bessie Churcher, she oversaw the activities of the Settlement, the playschools and the educational provision for disabled youngsters.

One of the last actions undertaken by Mary Ward concerned the latter. Janet Penrose Trevelyan (Ward’s youngest daughter), describes it thus:

Mrs. Ward succeeded, in the spring of 1918, in persuading the House of Commons to add a clause to Mr. Fisher’s great Education Bill, making it compulsory for Education Authorities throughout the country to “make arrangements” for the education of their physically defective children. She used for this purpose the machinery of the “Joint Parliamentary Advisory Council” which she had founded in 1913, but the bulk of the work—involving as it did the sending out of circular letters to ninety-five Education Authorities, the sifting and printing of the replies and the forwarding of these to every Member of Parliament—was carried out from Stocks, causing a heavy strain—long remembered!—on the secretarial resources of the house. (1923, Chapter XV).

In other words, it relied heavily on the work of Bessie Churcher and Dorothy Ward.

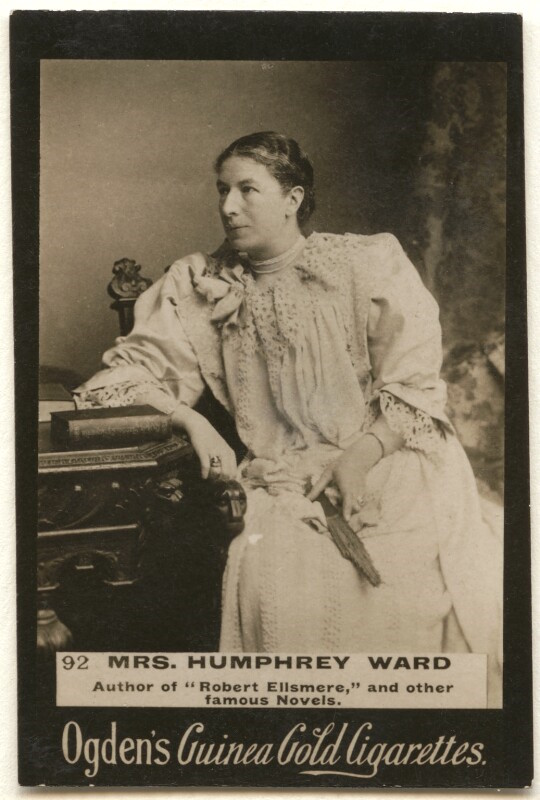

During the early years of the twentieth century, Mary Ward aka Mrs Humphry Ward was probably one of the most successful writers of her time. It was no accident that she was featured on a cigarette card. Today she is largely forgotten – but thanks to the efforts of Project Gutenberg the vast majority of her books are still available. Her concern, with others, about the needs of children and young people suffering from disabilities did lead to significant improvements in provision. Similarly, the importance of provision for children’s play remains recognized but not always well-funded by governments.

Mary Augusta Ward’s work was formally recognized in the 1919 New Year Honours when she was appointed as a Commander of the Order of the British Empire. She had battled with health difficulties for a significant proportion of her life, but late in 1919, she had a severe attack of neuritis in the shoulders and arms. Within a couple of months, she showed signs of bronchitis, together with significant heart problems. She died on Wednesday 24 March 2020 and was buried in the churchyard at Aldbury – not far from Stocks.

Humphry and Arnold

Humphry Ward and Dorothy Ward stayed at Stocks and began the task of selling the house, much of its contents, and the surrounding lands, to clear a ‘daunting set of outstanding debts and obligations’ (Sutherland 1991: 376). They left Stocks in February 1922 with a total of £5,325. In the process, many of Mary Ward’s letters were destroyed by Humphry. He and Dorothy moved to a small flat in Eccleston Square, close to Victoria Station in London. Dorothy continued to undertake tasks for the Settlement. Thomas Humphry Ward died on 6 May 1926, with his hand being held by Dorothy (op. cit.). He had not long finished writing a book on the history of the Athenaeum. Humphry was buried beside Mary in the graveyard at Aldbury. Dorothy Ward then went on to destroy many of his letters and her mother’s remaining papers. Around the same time, as John Sutherland (op. cit.) notes, her brother Arnold ‘went to live at the coast, where he apparently earned a living as a journalist’. On 1 January 1950, he died in a London nursing home. Dorothy was with him. The Bucks Herald (6/01/1950) in reporting his death and burial commented that ‘Illness hampered his life. He became a wide reader and a first-class bridge player. He was unmarried.’ He, like his father, was buried at Aldbury, alongside his mother. Dorothy, again, destroyed much of his surviving paperwork.

Janet

Janet Penrose Trevelyan, as chair of the Children’s Play Centre Committee, continued to oversee the work up to 1940 when she handed over 50 play centres to the London County Council (News Chronicle 23/06/1936 p.9 and Halifax Daily Courier and Guardian 10/09/1956 p. 4). She also initiated, and was secretary to, the successful Save the Foundling Site appeal over five years. It sought to purchase the site of the Foundling Hospital in Bloomsbury as a playground and welfare centre for children. Close to Mary Ward House, it is now known as Coram’s Fields – and is still enjoyed by large numbers of children. Janet Trevelyan was the vice-chair of the Council of Coram Fields up to her death. As a result of her efforts, she was appointed in 1936 as a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour. George Macaulay Trevelyan had received the Order of Merit (OM) in 1930 – and was later to turn down a knighthood both because the OM ‘was the only honour seriously worth having’, and that Janet ‘did not want to be Lady Trevelyan’ (Cannadine 1992: 18).

Unfortunately, the death of Theodore Macaulay in 1911 appears to have had a significant impact on the two remaining children. As David Cannedine notes:

As in most upper-class households, the children were brought up by nannies while their parents were busy with their good books and their good works; in addition, Trevelyan spent a great deal of time away, travelling and researching in Europe. And after the death of Theodore, both parents seem to have made a cult of him in a manner which can only have harmed his surviving siblings: making annual expeditions to the grave and weeping ostentatiously over their lost dauphin. (1992: 49)

There is some evidence that Mary Caroline and Charles Humphry thought of themselves as disappointments. However, as they grew up their relationship with their parents appears to have changed to some degree, particularly as they had their own successful careers. Charles Humphry graduated from Trinity College and became a lecturer in German. Later, he became a Fellow at King’s in 1947. He married Mary Trumbull Bennett in 1936 and they had five children. Charles Humphrey died in 1964 aged 55.

Mary Caroline gained a love of poetry and a kinship with Wordsworth in her childhood (Jonathan Wordsworth 1994). Her love of Wordsworth seems to have come about from exploring Langdale from Robin Ghyll, what was then ‘the Trevelyan cottage’ (it had previously been Dorothy Ward’s sanctuary). In 1930, Mary Caroline married John Moorman and ‘took on the role of vicar’s wife’. John was later to become Principal of Chichester Theological College, and then in 1959 the Bishop of Ripon. (op.cit). Mary Caroline had studied at Somerville College and embarked on several writing projects. These included William III and the Defence of Holland, 1672-44 (1930) (written as Mary Caroline Trevelyan), and her major two-part biography of William Wordsworth. Early Years, 1770-1803 appeared in 1957; and Later Years in 1966 (both written as Mary Moorman). Mary also became a trustee of the Wordsworth Trust in 1960 and later the Secretary, then Chairman, of the Trust. She retired in 1977. Mary Caroline Moorman died at home two weeks before her 89th birthday in 1994.

Janet Penrose died on September 7, 1956, in the Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. She had experienced a long and debilitating illness and spent some of this time at Hallington Hall, near Corbridge. George M. Trevelyan had inherited the Hall in 1928 and the family often spent Christmas and summer holidays there. His death came six years later, at Garden Corner, West Road, Cambridge – the house where he had lived on and off, also, since 1928.

Dorothy

Dorothy Mary Ward had died in 1964 aged 89. She had been living in Chelsea in Fernshaw Close, Fernshaw Road – a short walk away from the River Thames and a couple of miles from the old flat in Eccleston Square. Her assets amounted to £34,962. Dorothy’s ashes were buried with her mother in the Aldbury churchyard. Interestingly, she made several bequests to public institutions including, at the wish of her late father, three bronzes of female figures by A. W. Gilbert to the British Museum (or if not accepted, to such museum or gallery as her executors select). As a great-niece of Matthew Arnold and great-granddaughter of Dr Thomas Arnold, the famous headmaster of Rugby School, she left to the governors of the school a portrait of the doctor’s wife. The Rugby Advertiser (April 10 1964, p.10) carried the following piece:

ARNOLD LINK

PROBABLY the last link with a long past era was broken last week by the death in London of Miss Dorothy Ward, a great-granddaughter of Dr Arnold, of Rugby, at the age of 89. Miss Ward’s mother was Mrs. Humphry Ward the Victorian novelist whose father was Thomas Arnold, one of the eight children of the famous headmaster.She resided with and cared for her parents and then, on her mother’s death in 1920, carried on the social and welfare work which Mrs. Ward had initiated in London. The main place in her affection was held by the Mary Ward Settlement in Tavistock Place and by the playgrounds now known as Coram’s Fields.

See, also, Toynbee Hall, adult education and association

References

Briggs, A. and Macartney, A. (1984). Toynbee Hall. The first hundred years, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Cannadine, D. (1992). G.M. Trevelyan: a life in history. New York: W. W. Norton. [https://archive.org/details/gmtrevelyanlifei0000cann/page/n9/mode/2up. Retrieved August 9, 2024].

Cannadine, D. (2007). Trevelyan [née Ward], Janet Penrose (1879–1956). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press.

Dyhouse, Carol (1995). No Distinction Of Sex?: Women In British Universities, 1870-1939. London, Routledge.

Joannou, M. (2005). Mary Augusta Ward (Mrs Humphry) and the opposition to women’s suffrage. Women’s History Review. 14 (3–4): 561–580.

Keene, C. A. (2005). Oakeley, Hilda Diana (1867-1950), in Stuart Brown (ed.). Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Philosophers. Bath: Thoemmes Press.

Oakeley, H. D. (1939). My Adventures in Education. London: Williams and Norgate.

Short, K. (undated). The Mary Ward Settlement. London Metropolitan Archives. [https://web.archive.org/web/20131202221645/http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visiting-the-city/archives-and-city-history/london-metropolitan-archives/the-collections/Pages/mary-ward-settlement.aspx. Retrieved August 9, 2024).

Sutherland, J. (1990). The Mary Ward Centre 1890-1990. London: Mary Ward Centre.

Sutherland, J. (1991). Mrs Humphry Ward. Eminent Victorian, Pre-eminent Edwardian, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Trevelyan, J. P. (1920). Evening Play Centres for Children. The story of their origin and growth, London: Methuen.

Trevelyan, J. P. (1923). The Life of Mrs Humphry Ward, New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. Also available from Project Gutenberg.

Vicinus, M. (1985). Independent Women. Work and Community for Single Women, London: Virago.

Ward, H. (1926). History of the Athenaeum. London: Printed for the Club. [https://archive.org/details/historyofathenum0000ward/page/n7/mode/2up. Retrieved August 7, 2024].

Wordsworth, J. (1994). Obituary: Mary Moorman, The Independent 1st February 1994. [https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-mary-moorman-1391235.html. Retrieved August 11, 2024].

Young, A. F. and Ashton, E. T. (1956) British Social Work in the Nineteenth Century, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Links etc

The Mary Ward Trust have an interesting website that provides a virtual tour of the house plus material on some of the key people involved: http://www.themarywardhousetrust.org.uk/

Acknowledgements: The photograph of Passmore Edwards Settlement is by Charles S. Olcott, Public domain sourced via Wikimedia Commons. The photograph of Mrs Humphry Ward (Mary Augusta Ward) (1851 – 1920), Novelist and Social Worker, is believed to be in the public domain – wikipedia commons – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mary_Augusta_Ward00.jpg. The cigarette card of Mary Augusta Ward (née Arnold) was published by Ogden’ circa 1894-1907 and is part of the NPG Photographs Collection – NPG x136532 | ccbyncnd3 NPG licence. Mrs Ward by the Lake of Lucerne is by Dorothy Ward and included in Trevelyan (1923). It is believed to be in the public domain. The picture of Coram’s Fields is by Benjamin Ragheb flickr | ccbysa4 licence.

© Mark K. Smith 1997, 2024