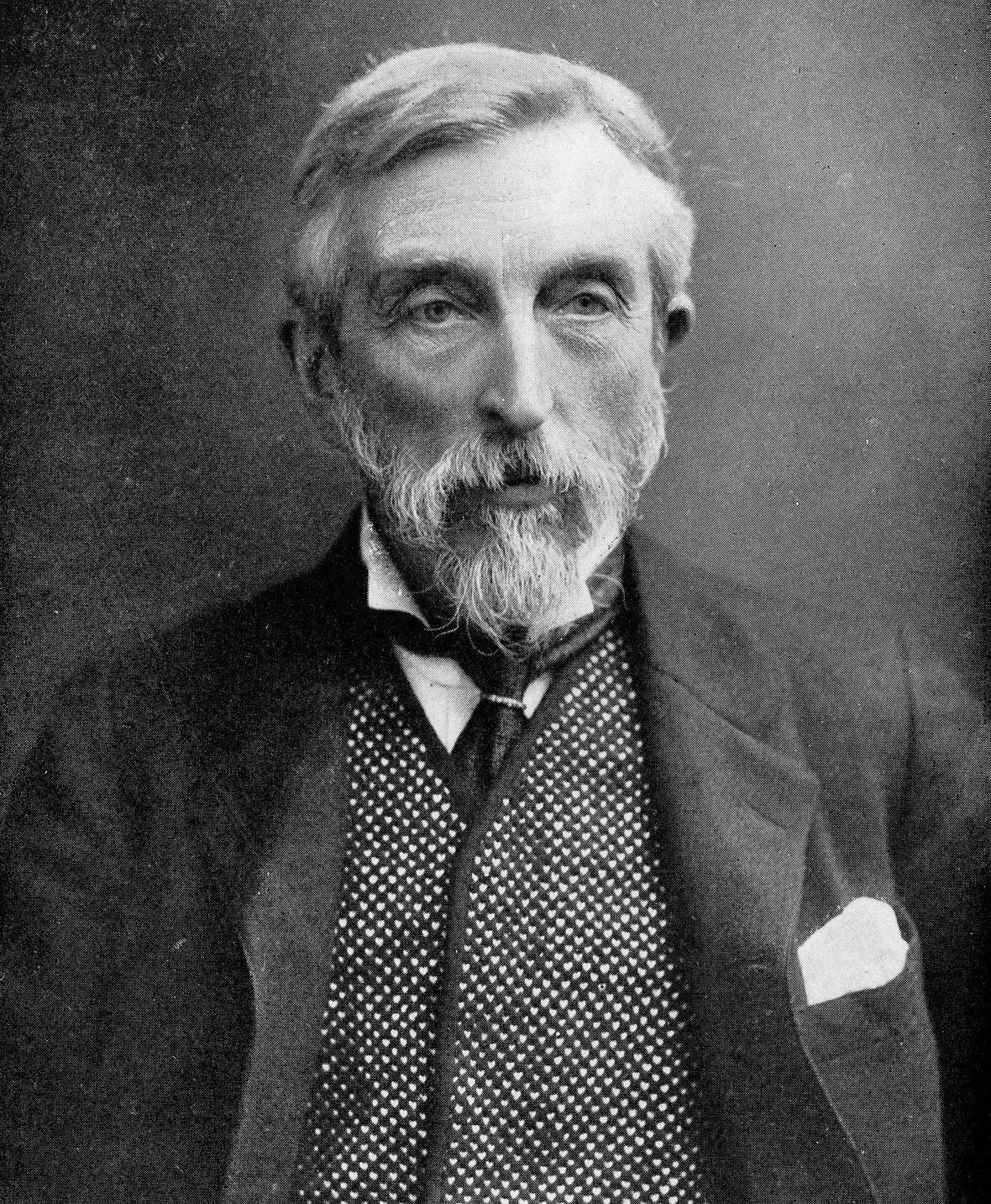

Charles Booth, The Wellcome Collection ccby4 licence

Charles Booth’s work in gathering data around poverty and wealth, both deepened the processes of social research and extended the attention given to it. He made a lasting contribution to the analysis of poverty and the development of government intervention to improve the situation faced by many.

Charles James Booth (1840 –1916) was born in Liverpool into a well-to-do family involved in shipping and the sale of corn. At 16 he was apprenticed into the company run by his father company. When his father died he joined with his brother Alfred to set up a company dealing in skins and leather and later took over the running of the firm. He was known for his fair business practices – and for his use of data in making decisions.

As a young man, Booth was also actively involved in politics – campaigning for the Liberal Party. He saw poverty at first hand while canvassing and appears to have been deeply affected by it. He had been brought up as an Unitarian but was not particularly religious. He did, however, have a strong sense of duty towards poor people – and a belief in action to improve their situation. One expression of this was his involvement in Joseph Chamberlain’s Birmingham Education League and, it appears, the undertaking of a survey in Liverpool which estimated that around 25,000 local children were neither at school nor at work.

In 1871 Charles Booth married Mary Macaulay, niece of the famous historian Thomas Babington Macaulay. Mary’s cousin was the Fabian, Beatrice Webb. They settled in London – and were soon involved in a circle that included key social activists as Octavia Hill, Henrietta Barnett and Samuel Barnett. He became involved in the the allocation of the Lord Mayor of London’s Relief Fund and looked to census data to help target resources. This led to Charles Booth questioning the quality of the data gained, and working to change the information gathered in the 1891 Census. At the same time he questioned claims made by a study undertaken by the Social Democratic Federation (and published in 1885), that found that up to twenty-five percent of the population of London were living in extreme poverty. Charles Booth decided to undertake his own inquiry starting in 1886. What ended up as Life and Labour of the People in London the work took until 1903. Three editions of the survey were published with the final edition consisting of 17 volumes.

The London School of Economics – which holds the Booth Archive, and has digitized the inquiry’s maps and data – describes the survey as follows:

The inquiry was organised into three broad sections: poverty, industry and religious influences. The poverty series gathered information from the School Board Visitors about the levels of poverty and types of occupation among the families for which they were responsible. Special studies into subjects such as the trades associated with poverty, housing, population movements, the Jewish community and education were also included. The industry series, working as a complement to the information already gathered about occupations from the School Board visitors, investigated every conceivable trade in London, from cricketers to wigmakers, to establish wage levels and conditions of employment. The series also covered the “unoccupied classes” and inmates of institutions, thereby including some fascinating material on the workhouses and causes of pauperism. The religious influences series – perhaps better described as social or moral influences – sought to describe these other forces acting on the lives of the people. As well as religion and philanthropy, it also covered local government and policing. [https://booth.lse.ac.uk/learn-more/who-was-charles-booth]

There are a number of striking features to the survey including the use of maps that were coloured coded to show patterns of wealth and poverty. Another, is the meticulous attention given to street by street data collection and analysis. [Click to download maps]

Social investigators such as Charles Booth (and Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree) provided both a spur for social action and arose from it. Many settlements combined both. Some of those associated with Booth’s efforts were involved in settlement work, some – like Beatrice Webb – became important political activists. Booth himself became a strong advocate of state old-age pensions as key means of alleviating destitution. His research had confirmed it as one of the commonest causes of pauperism. His work also helped to make the case for free school meals for the poorest children.

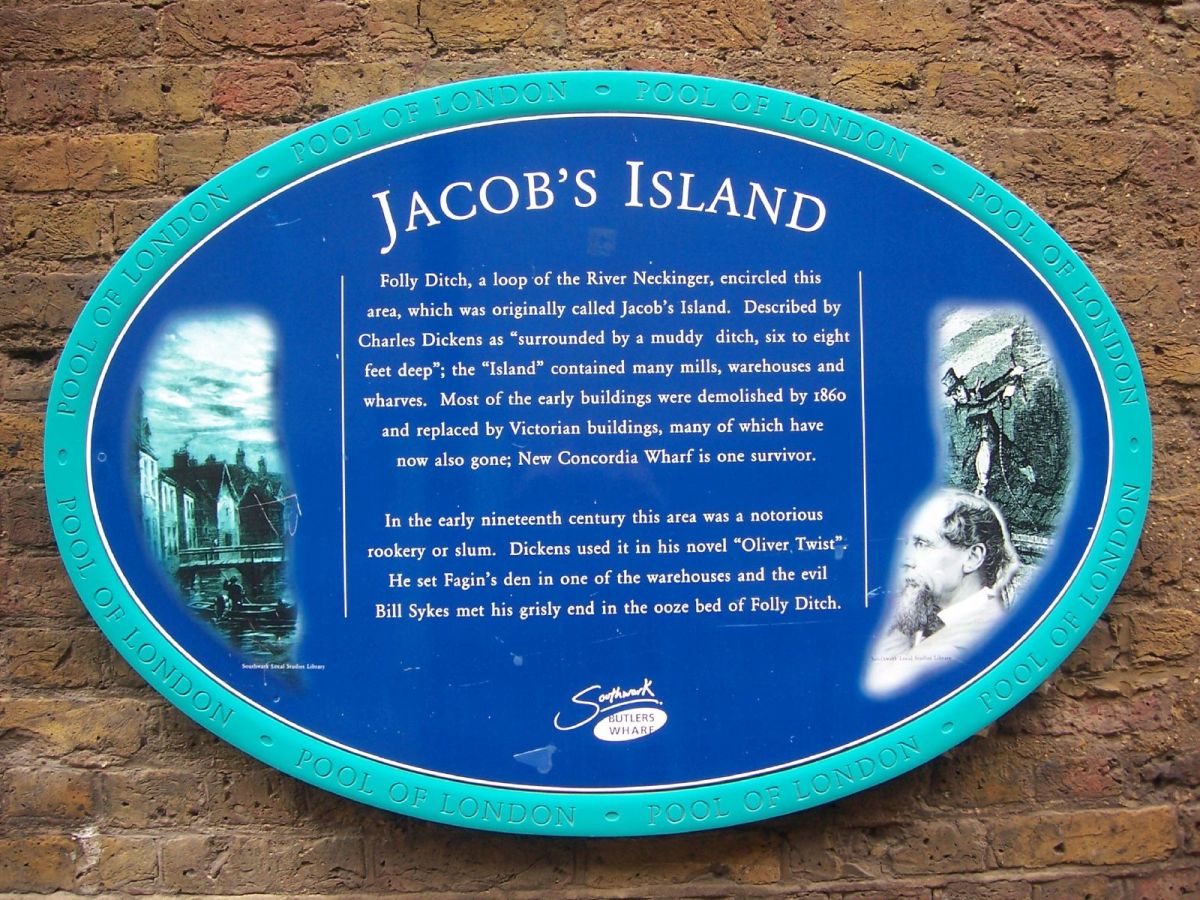

An example of the survey work – Jacob’s Island

Jacob’s Island was a setting for scenes in Oliver Twist. Dickens described it as ‘the filthiest, the strangest, the most extraordinary of the many localities that are hidden in London’. Industry and housing had developed around St Saviour’s Dock (the mouth of the now ‘lost’ River Neckinger) by the eighteenth century. The worst housing on Jacob’s Island was cleared in the nineteenth century to make way for warehouses. However, this was not before a major cholera epidemic in 1849-50 and a fire that raged for two weeks or more in 1861.

This area, like the rest of London, was studied by researchers involved in Charles Booth’s (1840-1916) famous social survey of London life – Life and Labour of the People in London. The map for this area (see opening image) in 1898-9 shows a concentration of ‘very poor’ households in chronic want (often employed as casual labourers) and ‘poor’ households (existing on between 18s and 21s ‘for a moderate family’). Much of this was on London Street (now known as Wolseley Street – right – named after Field Marshall Sir Garnet Wolseley – the original of Gilbert and Sullivan’s ‘modern major-general). It is marked on the map above. There were also some mixed streets. [link: Booth’s map of Jacob’s Island – type in “Jacob Street” (Southwark) and you will find the area. It stretches from Dockhead down to the river].

Acknowledgement: The picture of the Jacob’s Island sign is by sarflondonunc and is reproduced here under a Creative Commons licence (Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 Generic). Flickr – http://www.flickr.com/photos/sarflondondunc/2495909843/.

The original archival material (notebooks and poverty maps) used to create Charles Booth’s London is out of copyright. The digitised derivatives on the site are therefore licensed under a Public Domain Mark with no rights reserved, meaning that they have “No Known Copyright” associated with them. [https://booth.lse.ac.uk/about]

The picture of Charles Booth is part of the The Wellcome Collection and is reproduced here under a ccby4 licence. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/yb5ctajv CC-BY-4.0

First published in July 2019: updated June 2024.

© Mark K Smith 2019, 2024