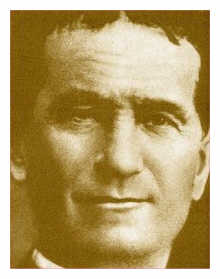

Rotherhithe children – Waldo McGillycuddy Eagar CBE circa 1933 – placed by the National Maritime Museum in Flickr Commons. Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) licence.

Here we explore the nature of social action through a walk in Bermondsey and Rotherhithe in London. This area has experienced severe poverty and disadvantage over the years. Settlements, missions and various government bodies have been involved in trying stimulate change – and some notable innovations were made. However, support and important change has also come from local people and their organizations.

The full walk and commentary follows. Further resources include: maps · doing the walk with a guide.

Stops: Introducing social action · Introducing Bermondsey and Rotherhithe · George Orwell and Tooley Street · Devon Mansions · London City Mission · Ernest Bevin · Dockland unionism · Bermondsey factory women’s strikes, 1911 · Maggie Blake’s cause · Docklands development · The battle of the houseboats · Charles Booth and Jacob’s Island · Oxford in Bermondsey · Alex Patterson/Across the bridges · The LCC and housing · Community work in the 1950s · Celebrity · Time and Talents and Dockhead youth work · Lesley Sewell and youth work · Two Towers TMO · Beormond Community Centre · On missions and settlements · The Bustins and Bermondsey Mission · Salmon and the Cambridge University Mission · Bermondsey Spa regeneration · Riverside School · John Scott Lidgett and Bermondsey Settlement · Grace Kimmins and playwork · Ada Salter, clean air and housing ·Alfred Salter · Waldo Eagar and the river · The lost world of Rotherhithe Street · Pearl Jephcott and married women working · Don Bosco and the Salesians · Time and Talents · St. Mary Free School · Rotherhithe Overground Station

The walk begins in Potters Fields on Tooley Street (close to the junction with Tower Bridge Road and to the rear of City Hall). This particular small, green area was, from 1586, an additional churchyard for St Olave’s Parish. Within a few metres of this point, we can see the sites of, and memorials to, significant social action. These include: philanthropic interventions around housing; community and union organization; religious evangelism and educational innovation; social commentary. As we continue the walk we will find a fascinating mix of social intervention, community action and social research.

Introducing social action

Here we explore social action. By social action we mean organized activity that seeks to improve human welfare, deepen civic culture and develop group life and commitment to others. Such a definition entails looking at the cultivation of a just and caring communal life. As such it involves a direct appeal to values and principles – and this will usually be grounded in some sort of shared belief system such as those that develop within religious institutions and social movements. Thus Catholic social action is likely to appeal to Catholic social teaching and ideas such as the dignity of the human person; human rights and duties; the social nature of the person; the common good; relationship, subsidiarity and socialisation; solidarity and options for the poor (Caritas 2003).

Many of the groups and organizations that today define their activities as social action have religious roots. Quaker Social Action, for example, began in 1867 as the Bedford Institute Association. Its initial work involved education such as children’s Sunday schools, and adult schools; religious efforts; moral training (including temperance meetings, penny banks and lending libraries); and relief of the sick and destitute. Settlements and the like were important breeding grounds both for social action thinking and activity, as were the traditions of local organizing that developed with unionism and the emergence of neighbourhood and community organizing.

links: caritas – catholic social action; quaker social action

Introducing Bermondsey and Rotherhithe

Bermondsey and Rotherhithe were, up until the Second World War, great centres of trade and industry. The wharves along the River Thames and Surrey Docks on the Rotherhithe peninsula handled a range of goods. Tooley Street was known as ‘London’s larder’, there were huge cold stores between Jamaica Road and the river, and Surrey Docks were the centre of the timber trade. Rotherhithe was significant for ship repair and barge building, and maritime-related industries like rope-making flourished. A roll-call of food processing industries grew in Bermondsey: Courage Brewery next to Tower Bridge, Cross and Blackwell in Crimscott Street, Pearce Duffs in Spa Road, Liptons on Rouel Road, and Peek Freans (first by St Saviour’s Dock, then on Drummond Road). Engineering and the leather trade were also important.

This was an area of considerable poverty and deprivation. Much of the work available was casual and wages were often low. Housing conditions were appalling with overcrowding, unsanitary conditions and absentee landlords. In addition, all the industrial activity made for poor air quality.

Philanthropists and social commentators were attracted to the area. It became a centre for social settlements and university and other missions. A range of innovatory and influential work emerged. The settlements, in particular, looked to social action. Local people also organized themselves through unions, political parties, and a range of local groups. Later, Bermondsey, in particular, was the focus of innovatory local government activity and there was a transformation of housing and environmental conditions.

The walk

We begin with George Orwell ‘s Down and Out in Paris and London which was written in part a few feet from the entrance to Potters Fields

George Orwell and Tooley Street

George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair – 1903-1950), the writer and social commentator, spent some time living in a doss house on Tooley Street when writing Down and Out in Paris and London (published in 1933 by Victor Gollancz). ‘The dormitory was … disgusting’, he wrote, ‘with the perpetual din of coughing and spitting — everyone in a lodging house has a chronic cough, no doubt from the foul air’ (quoted in Crick 1980). Parts of Down and Out.. were written in St Olave’s public library (which stood at the junction of Tooley Street and Potters Fields.

George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair – 1903-1950), the writer and social commentator, spent some time living in a doss house on Tooley Street when writing Down and Out in Paris and London (published in 1933 by Victor Gollancz). ‘The dormitory was … disgusting’, he wrote, ‘with the perpetual din of coughing and spitting — everyone in a lodging house has a chronic cough, no doubt from the foul air’ (quoted in Crick 1980). Parts of Down and Out.. were written in St Olave’s public library (which stood at the junction of Tooley Street and Potters Fields.

Following a brief career in the Burmese Police George Orwell had decided in 1927 to become a writer and to explore social conditions. He began living and journeying alongside tramps sometimes for several weeks at a time. This took him to the hop fields of Kent and to doss houses such as those in Tooley Street. An initial impetus was to see if the English poor were treated as badly as the Burmese. George Orwell also lived for a time in Paris taking low paid jobs and gradually developing his trademark, direct and plain style of writing. The first result was Down and Out in Paris and London. George Orwell’s journalism, novels and social commentaries (perhaps, most famously, The Road to Wigan Pier) were, and remain, deeply influential. They provide a graphic description of the sorts of conditions in which significant numbers of people were condemned to live and work during the 1930s. Later they were to be a significant element in several generations of socialists’ education.

Links: george orwell links – includes the full text of down and out in paris and london. Reference: Crick, B. (1980) George Orwell. A life, London.

Diagonally across the road, we see part of Devon Mansions – a housing initiative which stretches down Tooley Street to Dockhead (the picture below is of a section of Devon Mansions that stretches east from Tower Bridge Road).

Devon Mansions (formerly Hanover Buildings)

Behind Devon Mansions on the other side of Fair Street lies Naismith House. It can be seen just through the trees from Tooley Street. This is the headquarters of the London City Mission. It occupies the site of the old St John’s Church which was destroyed by bombing in the Second World War. To the west of the churchyard stood the Parish Street workhouse which originally served the parishes of St Olave and St John.

London City Mission

London City Mission [LCM] was founded in 1835 by David Nasmith and two friends. Nasmith had been involved in various religious improvement schemes and the establishment of city missions in Glasgow, Paris and New York. London City Mission began in a small terraced house by the canal in Hoxton. It was intended to be interdenominational, but there were difficulties with the Anglican church linked to David Nasmith’s tendency to over-extend himself via the formation of different associations and groups. The aim was to work among the largely non-church-going populations of inner-city areas who had been neglected by churches. London City Mission quickly attracted support and developed into one of the largest and most successful missions in the UK. Amongst other things, it pioneered and financed evangelists (usually linked with particular congregations, but sometimes ministering to particular groups such as dockers). The first paid missionary was Lindsay Burfoot in the Spitalfields neighbourhood (receiving £1 per week for his services). By 1885 it had some 460 staff.

As an evangelical organization, London City Mission had a significant philanthropic element. This continued even when others withdrew from this role. It was involved in the formation of ragged schools (including giving them their name). Working in the poorest districts, teachers (who were often local working people) used such buildings as could be afforded – stables, lofts, railway arches. There was an emphasis on reading, writing and arithmetic – and on bible study (the 4 ‘R’s!). They were important forerunners of youth work. LCM was also involved in providing coffee stores and the formation of mothers’ meetings (see Bible women). London City Mission remains a large and active organization combining the same mix of evangelism and social service. It moved to its then-new headquarters on Tower Bridge Road in the 1970s.

Reference: Thompson, P. (1985) To the Heart of the City. The story of London City Mission, London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Coming out of Potters Field we turn left along Tooley Street and cross into the small triangle with the two statues that lies next to Tower Bridge Road. The red brick building to our left is the former St Olave’s and St. Saviour’s Grammar School founded in 1571. This particular ‘Queen Anne’ building dates back to 1893-6 and was designed by E. W. Mountford (the architect of the Old Bailey and Battersea Polytechnic).

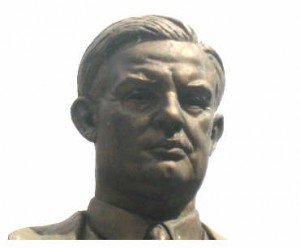

The two statues ahead are of S. B. Bevington the first mayor of Bermondsey and a local industrialist (he owned Neckinger Leather Mills) and Ernest Bevin (executed by E. Whitney-Smith in 1955).

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (1881-1951) was the first general secretary of the Transport and General Worker’s Union 1921-1940). He then entered Parliament serving first as Minister of Labour and National Service in Churchill’s War Cabinet (1940-5) and then as Foreign Secretary in Atlee’s government (1945-51). Bevin was born Somerset in 1881 to poor parents. Orphaned by the age of six and having the briefest of formal educations, he became a farm labourer. He moved to Bristol when he was eighteen where he worked as a van driver, became a Baptist lay preacher. Bevin joined the Dockers’ Union and later became a paid official. When the Dockers Union joined with over 30 other unions to form the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) Bevin was elected general secretary.

Ernest Bevin (1881-1951) was the first general secretary of the Transport and General Worker’s Union 1921-1940). He then entered Parliament serving first as Minister of Labour and National Service in Churchill’s War Cabinet (1940-5) and then as Foreign Secretary in Atlee’s government (1945-51). Bevin was born Somerset in 1881 to poor parents. Orphaned by the age of six and having the briefest of formal educations, he became a farm labourer. He moved to Bristol when he was eighteen where he worked as a van driver, became a Baptist lay preacher. Bevin joined the Dockers’ Union and later became a paid official. When the Dockers Union joined with over 30 other unions to form the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) Bevin was elected general secretary.

In the major dock dispute in 1920 Ernest Bevin argued the dockers’ case when the dispute went to arbitration. According to Howie (1986), he made a great impression, especially by exhibiting the actual amount of food a docker’s wages would buy. Through his advocacy, most of the demands were achieved and Ernest Bevin became known as the ‘the dockers’ KC’.

References: Bullock, A. (2002) Ernest Bevin. A biography, London: Methuen. Howie, Lord (1986) ‘Dock labour history’ in R. J. M. Carr (ed.) Dockland, London: NELP/GLC.

Dockland unionism

The work that dockers did was dangerous, heavy and precarious. In the 1850s the average wage was about 4d per hour. As Henry Mayhew put it at the time ‘Many of them, it was clear, came to the gate without the means of a day’s meal, and being hired, were obliged to go on credit for the very food they worked upon’. The docks were the site of considerable unrest and became the focus for union organizers. There were strikes in 1871, 1872 and most famously in 1889 with the battle for the ‘dockers’ tanner’. That strike was led by John Burns and Ben Tillett. The next major dispute came in 1920. Then it was Ernest Bevin who argued the dockers’ case. The unions continued to fight for decasualization. Industrial relations were tense. Through the 1960s and 1970s, there was a growing gap between local organizers and national union leaders. Howie has commented:

The dockers lived in a world of their own, with their own traditions and their own loyalties, mainly local. Their sense of loyalty was similar to that of the mining communities. They would react instinctively as a body in defence of any one their fellows threatened by injustice.

The role of, and demand for, dockers was changing rapidly. The development of mechanical handling (especially through the use of pallets and forklift trucks, and of tanks for liquids) had begun to be felt after the rebuilding of the docks following the damage of the Second World War. However, containerization put the final seal on the decline of London’s docks. Containerization entailed deep berths, specialist quayside handling equipment and a substantial road and rail infrastructure and capacity. These were easier to install on new sites. Employers were also keen to make a break with the local militancy of docker organization. The result was the closure of docks in quick succession (St Katherine, London and the Surrey Docks for example, in 1968-1970) and the emergence of Tilbury, downriver, as one of the largest container ports in Europe. This had a devastating impact both on local life and the local economy.

Reference: Howie, Lord (1986) ‘Dock labour history’ in R. J. M. Carr (ed.) Dockland, London: NELP/GLC.

Bermondsey factory women’s strikes, 1911

A landmark strike by women took place in Bermondsey in the summer of 1911. Some 15,000 women from over twenty factories with no particular history of union organizing spontaneously came out on strike. Most of the strikers were involved in food processing – many in jam making. As Ursula de la Mare (2008) has commented, these women were very poorly paid and had generally to endure adverse economic and social conditions. Actions by London dockers’ may have helped to stimulate their action – there was some help from docker’s leaders such as Ben Tillett (op. cit.).

After the strike began the National Federation of Women Workers moved in organizers – most especially Mary Macarthur. The result was the organisation of women in eighteen factories: jam and pickle makers, biscuit makers, tea packers, cocoa makers, glue and size-makers, tin-box makers and bottle washers (Cliff 1984 based on Drake 1920). Concessions were gained in a number of factories. For example, at Pinks’ jam factory (on Long Lane SE1), the wage rose from 9 to 11 shillings per week.

Some writers (e.g. Cliff 1984) have argued that this wave of activity led to a rise in women membership of the unions, which doubled between 1910 and 1914, and that the strike was an important impetus to militancy in the union movement. However, de la Mare makes the case for the strike being best seen as an independent, localized protest, supported by women trade unionists, but still separate from the wider industrial unrest of the time. That said, it did provide a powerful example of local action by women (many of whom were young).

References: B. Drake (1920) Women in Trade Unions. London ; Tony Cliff (1984) Tony Cliff, Class Struggle and Women’s Liberation. London: Bookmarks; Ursula de la Mare (2008) ‘Necessity and Rage: the Factory Women’s Strikes in Bermondsey, 1911’, History Workshop Journal 2008 66(1):62-80

We cross Tower Bridge Road, walk down Queen Elizabeth Street for a few metres, and then turn left down Horselydown Lane. The lane lay on the edge of Horsey Downe, a large field often used for fairs. It is said that King John was thrown from his horse here. At the bottom of the lane turn right onto Shad Thames. The building to your left (with the stairs going up and then down to the Thames is the Anchor Brewhouse. It is what is left of a large brewery (which extended up along much of Horselydown Lane and to the east) founded by John Courage in 1787. The brewery finally closed in 1981/2.

Walk a few metres along Shad Thames. On your left you will come to an alleyway leading to the river – Maggie Blake’s Cause.

Maggie Blake’s cause

Maggie Blake’s Cause is an alleyway connecting Shad Thames with the riverfront. Named after a local community activist it represents a significant victory – public access to the riverside in front of a section of Butler’s Wharf.

The main Butlers Wharf building was built between 1871-73. It is the largest and most densely packed group of Victorian warehouses left in London. With the development of mechanical handling and containerization, it fell into disuse with the last ship berthing in 1972. During the early 1970s, it briefly hosted a number of studios. Both David Hockney and Andrew Logan, had their studios in the area but Butlers Wharf was becoming derelict. In 1981, Sir Terence Conran, with his architectural practice Conran Roche and various business partners made a bid for mixed-use redevelopment which won approval from the LDDC. This included moving the Boilerhouse Project at the Victoria & Albert Museum to a new Design Museum at Shad Thames (it moved to Kensington in 2018). The Conran group focused on the waterfront, developing six buildings: the Butlers Wharf Building (with significant restaurant space, expensive apartments and some other office and commercial use), and the renamed Cardamom, Clove, Cinnamon, Nutmeg and Coriander warehouses. Back from the river, other architects and developers converted derelict space and Victorian warehouses into and commercial complexes. With the property downturn in the early 1990s, there was a gap in development – but by mid-decade a further wave of development took place.

Maggie Blake, along with other activists wanted to ensure that local people and the general public could walk freely along the south bank of the Thames. The developers wanted to restrict such movement – in particular so that space could be exploited for commercial purposes (largely eating).

Go through Maggie Blake’s Cause and walk along the riverside to just past Butler’s Wharf Pier. Across the river, you can St Katherine’s dock and some of the extensive development that took place in the last two decades of the twentieth century following the closure of the docks. One of these buildings (with a rounded roof) was the headquarters of the London Docklands Development Corporation for some years.

Picture: Bermondsey west by sarflondondunc | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence

Docklands development

The London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) was a significant feature of local for nearly seventeen years (July 1981 to March 1998). Established as the regeneration agency for the Docklands Urban Development Area by the then Secretary of State for the Environment, Michael Heseltine, it had a hand in much of the development that took place in the eight-and-a-half square miles of dockland stretching across Southwark, Tower Hamlets and Newham.

The Corporation became the target for a significant amount of local community action. Part of the reason for this was the extent to which it was an undemocratic body which had little or no relationship with local councils and planning authorities. A further, key, element was the perception that it consistently put the needs of big business above those of local people. This was especially the case on the Isle of Dogs where large-scale office developments took the place of relatively small scale industrial and housing developments; and in the Royal Docks where the proposal for, and eventually building of, London City Airport caused sharp splits in local opinion. In an area of significant poverty and housing deprivation, relatively little emphasis was put upon the encouragement of social housing – and just about all of the prime riverside sites went to developers concerned with the luxury market or with office and commercial development.

Links: LDDC History Pages

Continue walking along the riverfront past the Design Museum (cleverly converted in 1989 ‘Corbusian box’ from a warehouse) and the Paolozzi sculpture celebrating invention, and the next ‘warehouse’ block with Brown’s restaurant at ground level.

Ahead of you is St Saviour’s Dock (the mouth of one of London’s ‘lost’ rivers – the Neckinger) and beyond that some moorings.

The battle of the houseboats

The moorings on the Thames to the east of St Saviour’s Dock are the subject of a recent example of local community campaigning and activity. Barges and similar boats have used the moorings here by Mill Stairs (at Reed Wharf) for more than 200 years. However, the growing numbers of houseboats moored at the site, noise etc. linked to the barge renovation, and some issues around services to, and the organization of the moorings became a focus for discontent among some local residents and business people. They used various means to rid the moorings of the houseboats including seeking planning permission in 2004 for the stairs to be used as a point at which river ferries etc. could take on and put down passengers.

In response those living in the houseboats mounted a fascinating campaign using petitions, soliciting support from other local community groups, gaining celebrity endorsement e.g. Patrick Stewart, making very effective use of the local press and using the annual Britain in Bloom event to showcase their way of life and their campaign (some of the houseboat dwellers had spent some time creating garden space and enhancing the green potential of the boats). All this created a significant swell of support for their case and provided the right sort of environment for the planning hearing. This, effectively, ruled in their favour whilst making some requirements around the organization and servicing of the moorings.

Now cross the bridge (erected in 1999 for the LDDC). If you look up the dock you get something of a feel for the environment in the late nineteenth century. Many of the buildings housed steam mills processing the foodstuffs brought in on the boats. Wharves had developed here in the seventeenth century (it was initially used as a dock for Bermondsey Abbey). Tenements were erected in the early 1700s.

Go through the passage next to New Concordia Wharf, follow the path, and turn right onto Mill Street. Mill Street is named after the water mill established here by the monks of Bermondsey Abbey in the seventeenth century. You are now on Jacob’s Island

Charles Booth and Jacob’s Island

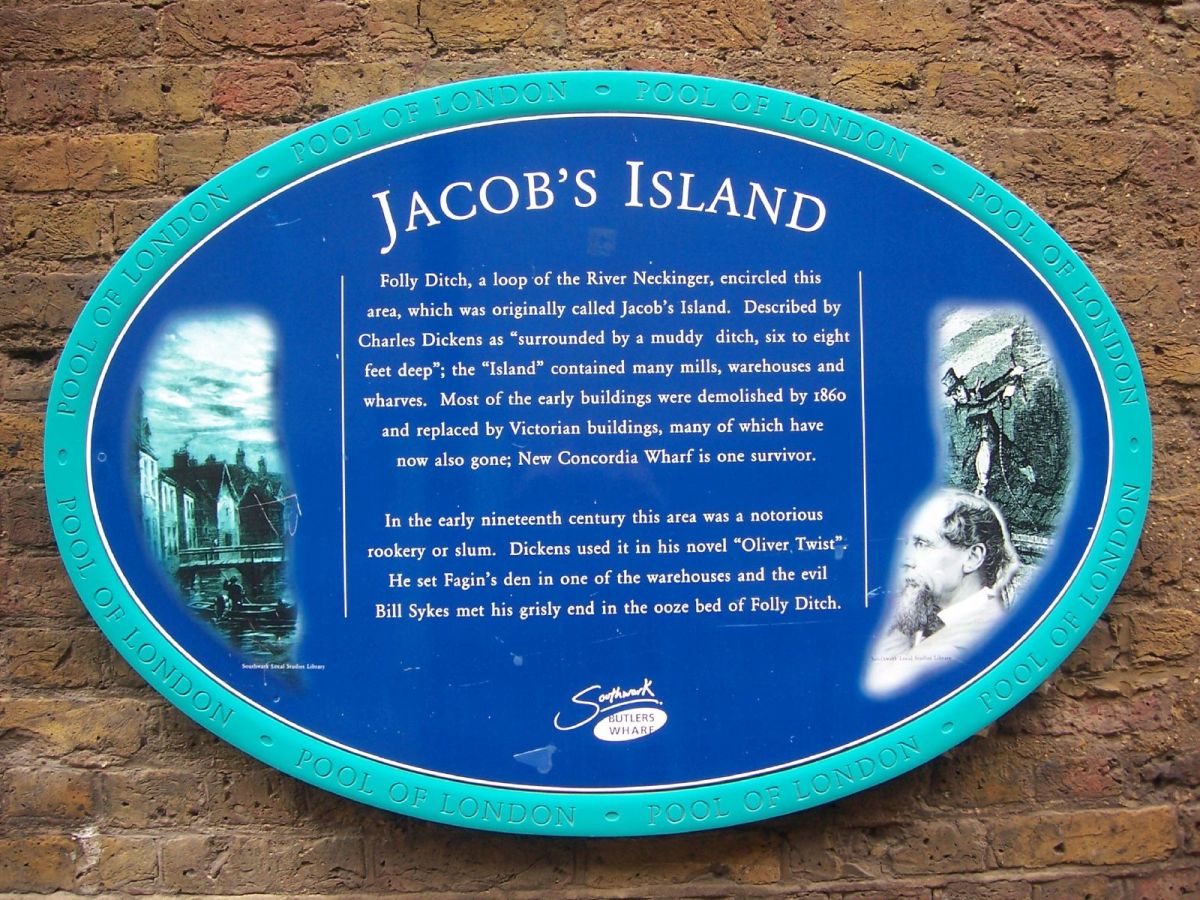

Jacob’s Island was a setting for scenes in Oliver Twist. Dickens described it as ‘the filthiest, the strangest, the most extraordinary of the many localities that are hidden in London’. Industry and housing had developed around St Saviour’s Dock (the mouth of the now ‘lost’ River Neckinger) by the eighteenth century. The worst housing on Jacob’s Island was cleared in the nineteenth century to make way for warehouses. However, this was not before a major cholera epidemic in 1849-50 and a fire that raged for two weeks or more in 1861.

The picture of the Jacob’s Island sign is by sarflondonunc and is reproduced here under a Creative Commons licence (Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 Generic). Flickr – http://www.flickr.com/photos/sarflondondunc/2495909843/.

This area like the rest of London was studied by researchers involved in Charles Booth’s (1840-1916) famous social survey of London life – Life and Labour of the People in London. A key element of the research was a series of maps coloured street by street to indicate the levels of poverty and wealth. The map for this area in 1898-9 shows a concentration of ‘very poor’ households in chronic want (often employed as casual labourers) and ‘poor’ households (existing on between 18s and 21s ‘for a moderate family’). Much of this was on London Street (now known as Wolseley Street – right – named after Field Marshall Sir Garnet Wolseley – the original of Gilbert and Sullivan’s ‘modern major-general). There were also some mixed streets.

Social investigators such as Charles Booth provided both a spur for social action and arose from it. Many settlements combined both. Some of those associated with Booth’s efforts were involved in settlement work, some – like Beatrice Webb – became important political activists. Booth himself became a strong advocate of state old-age pensions as key means of alleviating destitution. His research had confirmed it as one of the commonest causes of pauperism. [link: Booth’s map of Jacob’s Island]

Continue walking up Mill Street. On your right is New Concordia Wharf – a defining redevelopment completed in 1981 by Andrew Wadsworth’s Jacob’s Island Company. Wadsworth along with Conran’s Butler’s Wharf Company was central to developments in this area. As well as conversions such as this Wadsworth also used post-modern designs, for example in China Wharf and The Circle. Further developments follow – all housing luxury apartments and sometimes offices. When you get to Vogan’s Mill (distinguished by the white 17 storey tower) you need to turn right down Wolseley Street. Stop by the Fire Station. This is close to the building where the Dockhead Club was housed.

Oxford in Bermondsey

A group of ‘Oxford men’ who had a significant impact on youth work, social policy more generally, and the church were drawn to Bermondsey by John Stansfeld (‘The Doctor’) in the first years of the twentieth century. They worked in a group of clubs later known as the Oxford and Bermondsey Club. One of those clubs – Dockhead – was based in London Street (now know as Wolseley Street) in some derelict buildings bounded by Halfpenny and Farthing Alley, and next to The Ship Aground. A series of rundown and overcrowded courts ironically called Pleasant Row, Virginia Row and Pansy Row, and Wolseley Buildings were close by. The main club and residence were 600m away on Abbey Street.

Stansfeld chose Fratres as the motto for the work. It was in Barclay Baron’s words ‘the epitome of his oft-reiterated phrase “We are all brothers”‘ (1952: 34). It described both the ideal of the mission – and the way of working adopted by the residents and workers. The boys’ clubs had a strong emphasis upon ‘the lads making their own club’. This meant, for example, that it was they who regularly decorated and repaired the premises. They were also involved in the organization of activities and the life of the club. The club appears to have had a remarkable impact on both many of its members – and those who worked in it.

Those associated with the work included Alexander Paterson, now remembered as a prison reformer; Waldo McG. Eagar, a key figure in the establishment and development of the National Association of Boys’ Clubs; Philip (‘Tubby’) Clayton, the founder of TocH; William Temple and Geoffrey Fisher (both, later, Archbishops of Canterbury), and Basil Henriques and Reg Goodwin who both became central figures in the boys’ club movement (Goodwin also became the leader of the Greater London Council).

Alec Paterson also lived close by.

Alex Patterson/Across the bridges

Alexander Paterson (1884-1947) had a profound influence on social policy in Britain. Now remembered as a prison reformer, he was also key in the establishment of TOC H and influential in boys’ club work. Paterson’s book Across the Bridges (1911) was also an important and widely read exploration of poverty and social conditions of the dockland districts of South London.

Paterson was invited to Bermondsey by John Stansfeld (from the Oxford Medical Mission, later known as the Oxford and Bermondsey Club). He lived in the area for 21 years – and was in touch with the work throughout his life. Initially, Paterson lodged at the Mission – but he soon moved out into a two-roomed tenement close by ‘in the worst building he could find and in the roughest riverside street’ (we assume Woseley Street). There he fought ‘an unequal battle with vermin’ and became ‘will-nilly, the adviser of his teaming neighbours and the godfather of many of their children’ (Baron 1952: 163). His knowledge of local life from first-hand experience. His belief that there was goodness in all also gave his work a special character. Paterson had a humanizing influence on the prison system – especially with regard to the treatment of young people. Across the Bridges influenced the thinking and actions of a significant number of his contemporaries. Its call to action on the part of those who have wealth and influence, to cross the bridge to those who are less fortunate, was powerful.

References: Baron, B. (1952) The Doctor. The story of John Stansfeld of Oxford and Bermondsey, London: Edward Arnold; Eagar, W. McG. (1953) Making Men. The history of boys’ clubs and related institutions in Great Britain, London: University of London Press; Paterson, A. (1911) Across the Bridges or Life by the South London River-side, London: Edward Arnold.

Links: Oxford in Bermondsey

This area was extensively redeveloped in the interwar years. In particular, it benefited from considerable investment from the London County Council – and we see the results just across the road on what became known as the Dickens Estate.

The LCC and housing

Over the twentieth century, there was a major change in housing conditions and tenures in Britain. Owner occupation grew from 10% to 67% of the stock; private renting declined from 90% to less than 10%; and the social housing sector, largely in the form of council housing, grew to about a third before it’s reducing to less than a quarter. In London, direct state intervention in housing dates back to 1875 when the Metropolitan Board of Works took powers. Sixteen schemes rehousing around 23,000 people were carried out – with the Board doing the clearance work and then disposing of the sites to different companies to build artisan’s dwellings.

The London County Council (LCC) was established in 1889. Under the Housing of the Working Classes Act (1890) further areas were cleared but as no offers to build came in (the returns on housing were no longer attractive to investors) the Council began building housing itself. Between 1890 and 1914 nearly 10,000 units were built – largely for those who were regularly employed. With the Housing and Country Planning Act (1919) establishing the principle of state subsidy for housing – and pressure following the First World War to provide ‘Homes fit for Heroes’ – there was an acceleration of activity. The LCC also began to attend to the housing needs of the very poor. In the interwar period 97,000 council flats and houses were built. Initially, there was an emphasis upon creating new suburban estates beyond the London county boundary. With local political antagonism to these schemes, there was a return to building blocks of flats in the boroughs.

Much of the housing in the area immediately south of the river in Bermondsey was in an appalling state. The London County Council (LCC) had condemned the area around Wolseley Street and George Row as unfit for human habitation – and by the end of the 1920s land had been cleared and work begun on the classic five-storey blocks that now stand in the area (and form part of the Dickens Estate). In 1965 the London County Council and the lower tier of 28 metropolitan boroughs were replaced by the Greater London Council (GLC) and 12 boroughs. The GLC was abolished in 1986. Their responsibilities for housing passed to the boroughs.

Walk down the road opposite the fire station. On your right, you will see the priests house and the Most Holy Trinity Church. Parker’s Row is ahead of you.

This area suffered from severe bombing during the Second World War. With housing being so close to natural targets such as the riverside warehousing is probably not surprising that there was a significant loss of life and damage. For example, on March 2, 1945, a flying bomb demolished the priests’ house (killing three priests), a number of flats and shops were destroyed and a further 30 shops and flats, 60 houses and the fire station were badly damaged. Most Holy Trinity Church had been destroyed in a previous attack. As a result, this area became the focus for significant rebuilding and development after the war finished.

Community work in the 1950s

Community work was not generally viewed as a distinct occupation until the early 1960s. Prior to this, there were separate groups of workers such as community centre wardens, secretaries of councils of social services and development workers on new housing estates. Work on the Dicken’s Estate in Bermondsey during the 1950s is a classic example of the last of these. London County Council approached Time and Talents about putting in a social/neighbourhood worker to live in one of the many new flats being built. The worker’s task was to share in local life and to ‘encourage a community spirit amongst the tenants, helping them with their problems and promoting the best use of the Community Club’ (Daunt 1989: 85). Work began in 1951. The flat (in Wade House) was opposite the new estate club room (which also opened in 1951). One room was used as an office/small meeting room. The estate club was run by an elected management committee and financed by a 6d weekly membership fee paid by each member flat (pensioners could join for free). It had a large hall plus a laundry room. The Clubroom hosted a range of activities including a toddler’s group, a youth club (until it caused too much trouble!), locally organized variety shows, whist drives, films, and some classes. Annalies Becker – who worked there for five years – described it thus:

I lived on the Estate opposite the Community Hall, which was hired out for weddings and parties. The wedding celebrations at times became a bit wild and noisy. At other times the hall was used by a classical music group led by Lady Maud, who was bent on sharing the experience of exquisite musical enjoyment with all and sundry. But alas, the piano – so well tuned and cared for – on one occasion did not achieve anything but a string of cacophonies and, on inspection, it was discovered there was a breadknife lodged in the bowels of the piano! This had accidentally slipped in when the wedding cake from the previous night’s festivities was being cut. Consternation! I was never allowed to forget breadknife in the piano story! (Becker undated)

Today the clubroom is still in use with the old laundry turned into a bar, and the main hall used mostly for hirings.

Much of the worker’s time was taken up with visiting the old, sick and lonely, club children’s parents and tenants needing special help. For the first five or six years, the worker also spent time working with the management committee and the various groups associated with the club room. In addition, they arranged a number of direct activities, trips and clubs. Annalies Becker describes this work.

I also arranged for facilities for all age groups with a tenant’s management committee. We had outings for the elderly, visits abroad for mixed groups, of teenagers, house visits for the elderly, fundraising activities for local and national Time and Talents activities. I also took Social Work students to get their practical experience. The settlement house was nearby and we co-operated closely. It was a wonderful all-round experience with a lovely supporting group and endless scope for wider service.

Students came to visit or stay to gain experience in visiting and club work, and an American Fulbright scholar undertook some therapeutic group work with some ‘troublesome’ 12-year-old girls for a time (Daunt 1989). The project finished in 1960.

References: Becker A. (undated) Tread Softly. Scenes from my life. As told to Paul Marsden. http://homepage.eircom.net/~interfriendpublisher/tread.html. Daunt, M. (1989) By Peaceful Means. The story of Time and Talents 1887-1987, London: Time and Talents Association.

Carry on walking past the Wade Hall – on your left is a block of flats (Pickwick House), on your right is a school playground. You will come out onto George Row. To your left on the wall of Pickwick House you will see a blue plaque celebrating the contribution of Tommy Steele to popular music.

Celebrity

Jade Goody’s final journey through Bermondsey 2009

This was the gutter that Jade dragged herself from. It was here that Jade Cerisa Lorraine Goody on June 5, 1981, was born into a life of poverty and deprivation. Where she spent her early years with a mother with drug problems and a junkie jailbird father who hid guns under her cot.[News of the World, April 5, 2009]

Areas like Bermondsey have produced their share of celebrities – and have classically been demonized in order to accentuate the rags to riches nature of the stories. One small area along George Row in Bermondsey, for example, produced the singer and actor Tommy Steele (1936- ), the comedian Michael Barrymore (1952- ) and the reality star Jade Goody (1981-2009). The relationship of local people to those celebrities is complex.

There is the tendency fuelled by the mass media, as Christopher Lasch (1979: 21) has famously argued, of people warming themselves ‘in the stars’ reflected glow’. This can help to define people’s identity, but it can also encourage the desire for the same sort of popular recognition, wealth and lifestyle and the undervaluing of ‘ordinary’ life, communal involvement and relationships. According to Lasch, there has been a movement into a narcissistic culture where activities and relationships have become conditioned by the hedonistic need to acquire the symbols of wealth. Fired in significant part by consumerism, there has been a growth in individualization, the infantilization of adults and an undermining of a civic community (Barber 2007). At the same time, in local communities, there is often resentment at the success of ‘their’ celebrities – that somehow they didn’t deserve or merit fame and influence. Both reactions could be found in local responses to Jade Goody’s death in 2009. There was a lot of talk of her being a ‘Bermondsey girl’ and calls for the estate (The Dickens Estate) to be renamed in her honour. There were also questions about what she had ever done for the area (Southwark News March 26, April 2, 2009).

Questions about the contribution celebrities make to the communities of which they have been or are, a part has become more complex. Over the last twenty-five years or so entertainers, as Martina Hyde (2009) has commented, ‘have become an institutionalised part of charitable aid and activism, and are now a virtually unquestioned element of the response to intractable global problems’. The effect has been deeply damaging as ‘their extraordinary influence means that talking bullshit is not a victimless crime’. Hyde demonstrates celebrities have done little to further philanthropy. In the United States average charitable giving per household has remained more or less at this number for 40 years (at around 2.2%). She makes the point that the claim that celebrities are using their fame for good is hollow. Furthermore, it distorts debates and confuses issues.

Acknowledgements: The picture of Jade Goody’s funeral procession in the Blue, Bermondsey was taken by Steve Punter and is reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic Licence [http://www.flickr.com/photos/spunter/3413574891/].

References: Barber, Benjamin R. (2007) Consumed. How markets corrupt children, infantilize adults and swallow citizens whole. New York: Norton. Hyde, Marina (2009) Celebrity: How entertainers took over the world and why we need an exit strategy. London: Harvill Secker. Lasch, Christopher (1979) The Culture of Narcissism. American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. New York: W.W. Norton.

Turn right down George Row towards Jamaica Road. You will go past the school and nursery and then on your right you will see a hall. This was the site of a large, purpose-built girls’ club set-up and run by Time and Talents. The club was damaged by bombing during the Second World War – and was severely affected by subsidence (probably due to the impact of the the ‘lost’ River Neckinger.

Time and Talents and Dockhead youth work

Dockhead was the setting for some significant developments in clubwork. As well as the pioneering boys’ work undertaken by Oxford in Bermondsey, Time and Talents also did interesting work with girls and, significantly, with mixed groups. The first Dockhead club run by Time and Talents was established in a disused warehouse in 1903 at 1 Halfpenny Avenue (close to the Oxford in Bermondsey club for boys). They later moved to a shop in Jamaica Road, and then to an old public house in George Row – The White Hart. The area around them was condemned as unfit for human habitation – and as part of the rebuilding effort Time and Talents was offered a site to build a large, purpose-built club. The new Dockhead Club (on the corner of George Row and Abbey Street) opened in 1931 and had a large hall, club rooms, library, chapel, protected roof playground and five rooms for residents. The work included girls groups, cub and scout packs, and, crucially, mixed club work. The last took the form of the 50/50 club (the name was decided through a vote). It opened in the autumn of 1931 and was an experiment championed by the then warden, Honoria Harford. Another key figure in the development of clubwork was E. Lesley Sewell (1901-1975).

Reference: Daunt, M. (1989) By Peaceful Means. The story of Time and Talents 1887-1987, London: Time and Talents Association.

Leslie Sewell and youth work

E. Lesley Sewell (1901-1975) had won a mathematics scholarship to Newnham College, Cambridge (graduating in 1923) – but came to see her future in social work. She became Bursar and a Tutor at Time and Talents from 1925, and a Warden from the early 1930s. Marjorie Daunt has described her as ‘one of the great Settlement Wardens’.

She had more than her fair share of qualities which seem too good to be true, but they WERE true. Combined with a first class brain, she had great integrity and vision, a lovely sense of humour and fun and enjoyment of life. Modest withal, and transcending all, was her Christian faith. Her influence for good was tremendous. (Daunt 1989: 18)

E. Lesley Sewell’s experience of girls’ and mixed work at Time and Talents was put to very good use. She went on to be General Secretary of the National Association of Mixed and Girls Clubs (which then became the National Association of Youth Clubs) from 1953 to 1966. She joined the organization at the start of 1940 as Deputy Organizing Secretary. Under Lesley Sewell’s guidance, the Association developed a number of significant programmes and initiatives including Endeavour Training and Phab (Physically Handicapped and Able Bodied) clubs and responded to changes in the wider youth work environment (especially in relation to the Albemarle Report). Perhaps the best-known response was the growth of developmental and experimental project work – especially around detached youth work (see, especially, Mary Morse’s [1965] The Unattached). Honoria Harford. a previous warden and colleague at Time and Talents had also, earlier, joined the National Association as organizing secretary.

References:Daunt, M. (1989) By Peaceful Means. The story of Time and Talents 1887-1987, London: Time and Talents Association. See, also, in the archives Leslie Sewell’s booklet Looking at Youth Clubs.

Walk up to the traffic lights on Jamaica Road and cross. Then cross Abbey Street and turn left. On your right is Lupin Point, part of the Two Towers Housing Coop.

Two Towers TMO

Two Towers Housing Cooperative is an example of one of the key changes in housing policy in the mid-1990s. It is a tenant management organization (TMO). The residents control significant aspects of the running of the estate. In this case, Two Towers looks after cleaning, repairs, parking, rent collection and minor works (such as rebuilding the lift lobbies). They deal directly with developers etc. Major works such as lift replacements are still undertaken by the council. Two Towers is run by a committee and general meetings and employs its own estate workers. It has been in existence since 1999. Every five years residents have voted on whether to stay with the Coop or return to Council control. In 2004 some 97 per cent voted for the former.

Tenant management organizations have been promoted by the government. They significantly increase the numbers of people involved in local housing matters (because they have real powers), and of generally improve the service residents get. In the case of Two Towers, the Coop has focused on the quality and safety of shared environments like the lobbies, cleaning, the functioning of the lifts, and the speed and quality of repairs. Having local estate workers and the freedom to use different contractors helps in these matters, and boosted levels of rent collection. Involvement in the Coop or TMO can also lead to residents acting directly to deal with matters e.g. around graffiti. A further advantage of TMOs has been their development into organizations that provide or facilitate other local resources such as provision for children and young people.

There are often tensions with local authorities. The level of monitoring and administration required by them is substantial and has grown. There are conflicts around securing major works as TMOs have to compete for resources. Lastly, there are tensions around how TMOs see themselves and what local authorities believe them to be. Members of TMOs can tend to see themselves as community groups, representing the interests of local people, whilst local authorities view them as extensions of their administration.

Just beyond the gardens close by Lupin Point on the right (west) side of Abbey Street, you can see the Beormond Community Centre.

Beormond Community Centre

Community centres and associations have become a common feature of many local neighbourhoods. In Britain, their emergence is usually associated with the development of new housing estates following the First World War. Prior to this, there had been various initiatives and movements – notably the development of village and church halls (especially in the early decades of the twentieth century). There had also been influential developments in the United States (especially in Rochester) and Mary Parker Follett, in particular, had made a powerful case for centres and associations. One of the first recognizable associations was formed in Dagenham (Pettits Farm Association) in 1929. By 1938 there were some 304, 33 of which were in Scotland (Mess and King 1947: 73)

The Beormund Community Centre was established in 1982 as a result of community activity. Local people came together to form an action team to lobby the Greater London Council to make funds available for the purchase and conversion of the building (which had been a tannery – Nathenial Lloyds). They were successful and Southwark Council became the managing agents for the centre. A Management Committee was formed and charitable and limited company status followed in 1986/7. It is now the largest community centre in Southwark. It currently houses a purpose-built nursery, a gym and fitness suite, a training area (where there are both NVQ 2 and recreational programmes) plus a large community room which is used by a range of local community groups and individuals. A number of the training programmes are concerned with gaining ‘tools for the job’ (the centre is a JobCentre Plus provider). Sure Start is also a major user of the facilities.

Reference: Mess, H. A. and King, H. (1947) ‘Community centres and community associations’ in H. A. Mess (ed.) Voluntary Social Services since 1918, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co.

On the opposite side of the road from Lupin Point (at the corner of Abbey Street and Old Jamaica Road) is a new building (unnamed) which consists of flats and residences for retired missionaries and current young missionaries associated with the London City Mission. Up until 2001, the site was occupied by the Bermondsey Gospel Mission.

On missions and settlements

The work of missions and settlements has taken contrasting forms and been marked by political and theological difference. They were often concentrated in disadvantaged areas. In Bermondsey, for example, within a 400-metre diameter circle could be found in the early 1900s: three settlement houses – Time and Talents at Dockhead (broadly liberal and ecumenical), Bermondsey Methodist Settlement (ecumenical with a significant socialist agenda), and a forerunner of Bede; two missions with settlements – Oxford Medical Mission (broadly Liberal and evangelical [in the old sense]) and Cambridge University Mission) (‘low church’, evangelical and fairly conservative), and a number of independent missions.

Settlements were overwhelmingly inspired by the Christian faith of their founders and settlers. Their orientation was summed by Rev Samuel Barnett, when he talked of coming to work and live among the poor, ‘not in a patronising spirit but in a spirit of neighbourliness. You will find that there is more for you to learn than to teach’. They typically combined social service, research and campaigning work. A number of colleges also set up missions. Like settlements, they often involved people living in and serving poor areas; and had as a central form the club. Several undertook medical and dental work. Most were Anglican and some inclined toward evangelicalism. In contrast to settlements, such missions tended to be less campaigning and instead emphasized conversion. They often required or encouraged church attendance, and formed part of parochial systems. There were also independent gospel missions such as the Bermondsey Gospel Mission that focused on conversion and worship. Some were linked into larger organizations such as the London City Mission.

Reference: Doyle, M. E. and Smith, M. K. (forthcoming) Christian Youthwork. Lessons and legacies.

The Bustins and Bermondsey Mission

The Bermondsey Gospel Mission was founded in 1864 by Walter Ryall. It was initially known as the London Street Mission. For over a century it provided a setting for worship and local activity. In more recent years the Mission building was used as a residence and base for young missionaries working with London City Mission. The Mission site was redeveloped in 2000/1 by LCM. It still provides a base for young missionaries, some training rooms and some flats for retired missionaries.

Bermondsey Gospel Mission also provided the setting for a remarkable family saga. Walter Ryall’s daughter – known as Madam Annie Ryall – was a well-known gospel singer. She and her husband William Bustin ran the Mission from 1891 to 1946. At that point her son, Cyril Bustin, took over as superintendent and ran the Mission until to 1962. He had worked for the Mission in one guise or another for most of his life. Cyril Bustin also wrote a fascinating memoir – From Silver Watch to Lovely Black Eye. A portion of this memoir deals with his experiences as an Assistant Relieving Officer under the closing years of the old Poor Law.

After Cyril Bustin, the mission was led by Donald Mills until it was closed by the trustees in 1967. The building was then taken over by London City Mission.

Reference: Humphrey, S. (2004) Bermondsey and Rotherhithe Remembered, Stroud: Tempus.

Cross to the west side of Abbey Street and walk down Old Jamaica Road. On your left, on the corner of Marine Street and Old Jamaica Road, you will see a newish development – The Salmon Youth Centre.

Salmon and the Cambridge University Mission

Cambridge University Mission (now the Salmon Youth Centre) was founded in 1907as medical mission with a boys mission club and residential settlement. The chief instigator was the Rev. Harold D. Salmon (who became the first head of settlement – 1907-21). Concerned about the condition of young people in Bermondsey he gained the support of a group of Cambridge evangelicals (partly based around Ridley Hall). A building on Jamaica Road was bought and refurbished in 1907; further land and new halls added in 1910. A girls branch followed in 1916. In 1922 the name changed to the Cambridge University Mission Settlement. The early workers were described by Eagar (at the nearby Oxford and Bermondsey Club) as a ‘stricter section of Low Churchmen’. Certainly Salmon was to fall out with the local vicar of St James and appears to have given a wide berth to the other local settlements.

A significant number of Cambridge undergraduates and graduates found their way to the Mission – sometimes during vacations, often when undertaking further study in London (especially medical training). While the residential element had to close during the Second World War (the building was also damaged by a land mine) it reopened in 1947/8 – and uniquely among BASSAC members has continued up until today. The buildings were significantly rebuilt during the 1950s, then demolished in 2004/5 for a redevelopment which included a sports hall, drama space, chapel, residences, and some housing (provided with Hyde Housing).

Walk on – the tower to your left is part of the Two Towers Housing Co-op and the new development to your left is part of a housing scheme initiated and run by Hyde Housing – a housing association.

Picture: Bermondsey west from the top of Casby House by sarflondondunc | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence

Bermondsey Spa regeneration

Over the last decade or so, community-oriented forms of work within local neighbourhoods have withered in England. The buzzword has become regeneration. It involves a much harder focus on economic development and the renewal of physical assets such as housing.

The Bermondsey Spa Regeneration is a good example of this trend. It entailed Southwark Council setting out a vision for the neighbourhood (with some consultation with local people and ‘stakeholders’) and putting parcels of land up for sale. Developers then had to submit detailed proposals, their merits and issues were assessed, and a sale made to what appeared to be the ‘best’ proposal. Most of the initial schemes involved between 25 and 30 per cent of social housing (close to the minimum required) and a high proportion of one and two-bed flats. Schemes had to conform to the Mayor of London’s requirements for high-density housing in inner-city planning zones. Developers had to consult with local stakeholders such as local agencies, tenants groups and community organizations.

The eventual developer for the area south of Jamaica Road was Hyde Housing (a housing association) after the preferred, developer dropped out following the slow down in the property market. This has meant a much higher proportion of properties for rent and for key workers. However, the scheme still follows the national trend in having a very high proportion of two-bed flats. In 2005 Propertyfinder reported that 41 per cent of new units were two-bed flats or starter homes with only 20 per cent of buyers wanting such properties. Overall, there was a shortage of some four million three-bed houses and apartments. Building work began in 2005 and ended in 2015.

Carry on walking along Old Jamaica Road. Take the path between the school playground and the churchyard. At the end of the path is the Gregorian public house. Across the road ahead of you (St James’ Road) is a new apartment block. On the site of the block of flats beyond it was based another settlement (which later became Bede House).

Cross to the north side of Jamaica Road either by the underpass or via the traffic lights. Ahead of you is Bevington Street. Cross Scott Lidgett Walk down Bevington Street. About 150m on your right is a school.

Riverside School

In 1868 as deputy president of the Board of Education William Edward Forster (1818-1886) was charged with developing a national system of education. There had been debate around the role of church schools (and the voluntary societies largely organizing them) and concerning the lack of provision for many children. His Elementary Education Act 1870 established popularly elected (by ratepayers) local school boards and gave the right to women to vote and be candidates. The Boards had to examine elementary education provision in their area. If there were not enough places, they could build and maintain schools out of the rates. The activities of both the Boards and the voluntary societies seeking to maintain their position led to some 4,982 schools being set up by 1874 (8,281 were already established).

Riverside School was one of the first generation of schools designed for the new School Board for London (established 1870). Built in 1874, to the design of M. P. Manning it continued in the Gothic style commonly used up to around 1870 and is ‘an early and fine example of London School Board architecture’. It makes good use of a cramped site. There is a ground floor playground and it opens to the front in an arcade. The next generation of London schools was built in a Queen Anne style and generally followed a pattern developed by E. R. Robson (the Board’s architect) based on German schools. Instead of a large hall with tiered seating for classes, these had separate classes opening out from the hall – a design that was adopted by many other boards. School boards were important in encouraging local democratic participation in schooling. They involved direct local oversight of schooling and could be a counterbalance both to the power of heads and of central government. They were replaced by local education authorities under the Education Act 1902.

Reference: Williamson, E. and Pevsner, N. (1998) London Docklands. An architectural guide, London: Penguin.

Carry on walking down Bevington Street. Again, to your left, you can see how close housing came to the warehouses and docks that were the lifeblood of the area. At the top turn right onto Bermondsey Wall East. Just past the public house you will see Farncombe Street. Bermondsey Settlement (see below) was close to the school.

John Scott Lidgett and Bermondsey Settlement

Rev. John Scott Lidgett (1854-1953) established Bermondsey Settlement in 1891. It was to be the only Methodist settlement and provided an opportunity for better-off Methodists to live in a deprived area and to share the lives of people there. John Scott Lidgett had a vision of the settlement as a ‘community of social workers who come to a poor neighbourhood to assist by methods of friendship and cooperation those who are concerned with upholding all that is essential to the well-being of the neighbourhood’. He argued for stronger action to advance the social, economic and spiritual conditions of the working classes. As well as becoming the Warden of the settlement, John Scott Lidgett was an important Methodist theologian arguing for tolerance and Christian unity. He was a strong advocate of the formation of the Wesley Guild (1890) which became the main means of organizing work with young people within the Methodist Church (the Guild also involved older people). The Guild had 152,000 members in some 2000 groups by 1900. He was also recognized as the principal architect of Methodist Union in 1932. Scott Lidgett was not afraid to engage in politics. He became was an alderman on the London County Council and leader of the Progressive Party on the LCC between 1918 and 1928. He was made a Companion of Honour in 1933.

Bermondsey settlement hosted a range of innovatory work and attracted some significant residents and helpers including Ada Salter, Alfred Salter and Grace Kimmins. The settlement finally closed in 1969.

Reference: Tuberfield, A. (2001) John Scott Lidgett: Archbishop of Methodism?, Eastbourne: Epworth Press.

Grace Kimmins and playwork

Bermondsey Settlementhad a particular concern for children’s play. Mary Ward (at the Passmore Edwards Settlement) had pioneered the development of play centres and playgrounds during the early years of the twentieth century and had advocated and organized around better schooling provision for those with disabilities. Workers at Bermondsey also developed provision and had strong links with a number of geographically close and related initiatives at Passmore Edwards, West London Mission (run by the radical Nonconformist leader, Hugh Price Hughes 1847-1902) and some organized by the feminist Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (1867 – 1954), Mary Neal (1860 – 1944) and others.

Perhaps the most significant figure was Grace Kimmins nee Hannam (1871-1954). Grace Kimmins joined the settlement in late 1895 and lived in ‘a spartanly furnished working-class flat in Rotherhithe’ (Koven 2004). With other workers at Bermondsey settlement she set up the Guild of Play. Grace Kimmins argued that education should not be confined to school timetables and scheduled hours but it should, ‘invade all public playing-spaces, parks and open places as well as halls of entertainment, and even the streets and alleys of towns and cities’ (Brehony 2001). She described the purpose of the Guild of Play as that of the provision for ‘little girl children’ of, ‘vigorous happy dances for recreative purposes on educational lines’ (op. cit.). Koven (2004) suggests that Grace Kimmins was influenced by John Ruskin’s ideas about the redemptive power of beauty and that she ‘viewed children’s play as a vital moral agent in the transformation of individuals and society, and as a way to examine the history and ethnography of nation, race, and empire’. She explored these themes and the experiences of children in the slums in her novel: Polly of Parker’s Rents (1899).

Grace Kimmins also helped to set up The Guild of the Poor Brave Things when working at West London Mission (as Sister Grace) in 1894. It sought to promote the use of alternative pedagogies – including play – in the education of those with disabilities. The Guild was to be based at Bermondsey Settlement for some time.

In 1898 Grace married the child psychologist Charles William Kimmins (1856–1948), a London county council inspector of education, and resident at the men’s branch of the Bermondsey settlement. Both were deeply committed to improving the welfare of poor and disadvantaged children and this bore fruit in a further innovation the Heritage Craft School and Hospital. Established initially in 1902 in a derelict workhouse at Chailey in Sussex not far from where she was born, this residential centre had the aim of enabling those with a disability who showed a particular craft talent to train and if possible become self-sufficient. Helped by Alice Rennie and supported by Scott Lidgett, the Heritage School and Hospital was to be the centre of Grace Kimmins work for the remainder of her life. It became a major therapeutic centre

References: Brehoney, K. (2001) A “socially civilising influence”? Play and the urban ‘degenerate’, http://www.inrp.fr/she/ische/abstracts2001/BrehonyP.rtf

Seth Koven, ‘Kimmins, Dame Grace Thyrza (1870–1954)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edition, May 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/34315, accessed 4 Aug 2008]

Turn back up onto Bermondsey Wall East until you come to Wilson Grove. Turn right and walk a few metres.

Ada Salter, clean air and housing

Ada Salter was initially a resident at Bermondsey Settlement. She was deeply moved by the condition of people in London, and Bermondsey in particular. With Alfred Salter she made a significant contribution to the life and welfare of the area. A committed pacifist and Quaker she was imprisoned for a short time during the First World War. She became the first woman councillor (1910) and woman mayor in London and the first Labour mayor in Britain (1922).

Two of the most visible signs of her work are the trees that populate Bermondsey streets and parks and the housing in the Wilson Grove area. Ada and Alfred Salter saw at first hand the disastrous effects of industrial and domestic pollution. Ada’s championship of tree planting resulted in a major programme of work and had a significant effect on air quality in the borough.

The cottages in Emba Street, Wilson Grove and Marigold Street were also the results of the Salter’s efforts (and are now known as ‘Salter Cottages’). Built in 1928 (and designed by Culpin and Brothers) they are one of the first attempts in London to provide municipal housing in “garden village” form.

Return to Bermondsey Wall East and turn right (east). On your left, you will see Cherry Gardens Pier (where the City Cruisers operate from). This area was a well known recreational area in Stuart times – and was particularly popular on Saturday afternoons. Samuel Pepys records in his diary coming to the gardens to buy cherries for his wife. Much of the riverside had the usual mix of wharves and warehouses – with some public houses, offices and residential buildings mixed in.

A number of people involved with Oxford and Bermondsey, such as Hubert Secretan, lived in this immediate area – often in quite poor conditions.

Walk on past Naylors and Corbett’s Wharf. As you come past National Terrace (a late twentieth-century development on your left) you come to an open space. To the left of the space you used to find a sculpture by Diane Gorvin ‘Dr Salter’s Dream’. Alfred Salter looks at his daughter (who died age nine). Their cat looks on. (This piece was originally on the promenade by Cherry Gardens – but local residents complained that the sculpture had become a gathering place for young people – so it was moved! It was then stolen.

Alfred Salter

This is a picture of the original statue – it has been replaced by a new version

Dr Alfred Salter (1873-1945) studied medicine at Guy’s Hospital and was drawn to set up in practice in Bermondsey in 1900 following a period of residence (from 1898) at Bermondsey Settlement. Alfred Salter later described the conditions he found in the 1890s. ‘Water was drawn from one standpipe for 25 houses, “on” for two hours daily but never on Sundays. There was no modern sanitation and only one WC and cesspool for 25 houses. Queues lined up each morning, often standing in rain or snow. It was utterly impossible to maintain bodily cleanliness. The conditions of thousands of homes were the same at the time’. Whilst at the settlement Salter organized mutual insurance schemes around health and a men’s adult school.

Alfred Salter understood the limits of individual effort and became active in politics. Elected to Bermondsey Council in 1903 and MP for the constituency from 1922 (as a member of the Independent Labour Party) he and his wife Ada Salter made a profound difference in the area. As well as working to improve housing and environmental conditions, he helped to establish a comprehensive local health service – with facilities unknown in this sort of area and an emphasis upon health education (making early use of film). Sadly, Ada Salter and Alfred Salter had direct experience of the problems families experienced in the area. While living in Storks Road (just off Jamaica Road) their only child died, aged eight, from scarlet fever.

Alfred Salter was a committed Christian and pacifist (being involved with the Quakers for a number of years). He also was a strong advocate of Guild Socialism and associationalism.

Reference: Brockway, F. (1949) Bermondsey Story. The life of Alfred Salter, London: George Allen and Unwin.

Carry on walking alongside the river. To your right you will see the ruins of a manor house (c.1350) built for Edward III, and to your left the Angel Inn. (An inn has stood on this site since the fifteenth century – built by the monks of Bermondsey Priory. The present building dates from the early nineteenth century. Captain Cook prepared for his voyage to Australia at the old inn and Samuel Pepys was a visitor). Walk past the inn. Ahead you will see a single building on the riverside (at the end of Fulford Street). There is a set of watermen’s steps by its side (The Kings’ Stairs).

Waldo Eagar and the river

Waldo McGillicuddy Eagar (1884-1966) was, for a number of years, associated with, and warden of, the Oxford and Bermondsey Club in Southwark (then known as the Oxford and Bermondsey Mission). He played an important role in the formation and running of the National Association of Boys’ Clubs. Waldo Eagar also wrote the classic statement of Principles and Aims of the Boys’ Club Movement, along with Basil Henriques, Lionel Ellis and Colonel Campbell (Ellis and Campbell were joint secretaries of NABC) Later 1953 he wrote a classic history of boys’ work Making Men (1953).

While living in Bermondsey Eagar began photographing the Thames and the life of the people who lived and worked along its shores. The resulting collection (a significant part of which is held in the National Maritime Museum) is described as forming ‘a remarkable document of a maritime community that no longer exists’ (PortCities: London undated).

Links: PortCities: London – View some of Eagar’s photographs – Letts Wharf, Commercial Dock, Rotherhithe children, Royal Victoria Gardens. One of his photographs – Boys at a Rotherhithe Wharf – featured the foreshore by the King’s Stairs.

Walk on a few metres past the building. Stop. This was the bustling centre of Rotherhithe.

The lost world of Rotherhithe Street

The western end of Rotherhithe Street and the adjoining streets was, in many respects, the heart of Rotherhithe. Today only one property remains – No. 41, a house which for many years was offices for Braithwaite and Dean, Lightermen. The buildings to the west of No. 41 up to the Angel Public House were either destroyed by a fire just before the Second World War or by bombing at the start, the buildings to the east by London County Council in the early 1960s.

The riverfront properties had largely been occupied by barge builders and repairers and before that sail-makers and mast-makers. The historic ‘Jolly Waterman’ public house also stood here and was in use up until the 1950s. Many of the buildings were mid-eighteenth century and featured in James McNeill Whistler’s well known ‘Thames Set’ of etchings. By the 1950s the buildings had become popular among a certain artistic set. Anthony Armstrong Jones lived here and it was said that Princess Margaret was a frequent visitor (Ellmers and Werner (1988). The London County Council were ‘determined to replace this ancient vitality with parkland’ (Humphries 2004: 35). There was a campaign to save the houses and some of the character of the area. Sir John Betjeman and others tried to make the case for alternative developments – but they failed.

References: Ellmers, C. and Werner, A. (1988) London’s Lost Riverscape, London: Viking; Humphries, S. (2004) Bermondsey and Rotherhithe Remembered, Stroud: Tempus.

Just past what was No 41 Rotherhithe Street – and close by the post at the top of the steps commemorating Queen Elizabeth II golden jubilee – another important social organizer and researcher lived for eight years at 47 Rotherhithe Street – Pearl Jephcott.

Pearl Jephcott and married women working

Pearl Jephcott (1900-1980) was a talented social researcher and organizer. For nearly twenty years she helped to develop and sustain girls’ and mixed clubs. Alongside this work, Jephcott also began researching and writing about the lives and experiences of young people. Unlike many other researchers, she placed an emphasis on exploring the experiences and circumstances of ‘ordinary’ young people. Her research broadened out to studies of particular neighbourhoods and social phenomenon. She was the first person to research and write at length about the experiences of people living in tower blocks; undertook an important study of Notting Hill following the ‘race riots’ of 1958; undertook a major study of married women working. This last study brought her to live in Bermondsey.

Pearl Jephcott (1900-1980) was a talented social researcher and organizer. For nearly twenty years she helped to develop and sustain girls’ and mixed clubs. Alongside this work, Jephcott also began researching and writing about the lives and experiences of young people. Unlike many other researchers, she placed an emphasis on exploring the experiences and circumstances of ‘ordinary’ young people. Her research broadened out to studies of particular neighbourhoods and social phenomenon. She was the first person to research and write at length about the experiences of people living in tower blocks; undertook an important study of Notting Hill following the ‘race riots’ of 1958; undertook a major study of married women working. This last study brought her to live in Bermondsey.

Married Women Working (Jephcott with Sears and Smith 1962) throws considerable light on the experiences and situations facing women and was published at a time when there was often ill-informed, debate around the subject. However, one of the most engaging features of the book is the way in which Pearl Jephcott was able to get inside the lives of local people in Bermondsey and to present their experiences truthfully. She drew upon the experiences of her neighbours – and was able to mix this with data gained from more formal interviews and research in a local large factory – Peek Freans. The result was an insightful picture of the processes of ‘home-making’, working and raising children.

link: Pearl Jephcott and the lives of ordinary people

Walk away from the river down Fulford Street until you come to Paradise Street (a name like this was the sure sign of a slum!). The church to your left across Paradise Street is St Peter and the Guardian Angels (built in 1902). The building to the right is the Bosco Centre, a Salesian house.

Don Bosco and the Salesians

Don Bosco (1815-1888) was a talented educator and animateur. He was particularly concerned with the needs of young people. His work initially looked to encourage work with children and young people in the sorts of settings familiar to youth workers. The main form he adopted  was the youth oratory – a mixture of what might be called a youth club and a youth parish. Later he was to turn his attention to schooling, particularly trade schools. His educational system is often described as the ‘preventive system’. It was an approach built on love and the character of the educator. The concern, in Don Bosco’s words, was for learners ‘to obey not from fear or compulsion, but from persuasion. In this system, all force must be excluded, and in its place charity must be the mainspring of action’. He taught that educators should act like caring parents; always be gentle and prudent; allow for the thoughtlessness of youth; be alert for hidden motives; speak kindly; give timely advice; and ‘correct often’. Alongside love, Don Bosco stressed the importance of reason and religion. His educational method was largely developed through reflection upon his own experience and disseminated through letters, talks and example.

was the youth oratory – a mixture of what might be called a youth club and a youth parish. Later he was to turn his attention to schooling, particularly trade schools. His educational system is often described as the ‘preventive system’. It was an approach built on love and the character of the educator. The concern, in Don Bosco’s words, was for learners ‘to obey not from fear or compulsion, but from persuasion. In this system, all force must be excluded, and in its place charity must be the mainspring of action’. He taught that educators should act like caring parents; always be gentle and prudent; allow for the thoughtlessness of youth; be alert for hidden motives; speak kindly; give timely advice; and ‘correct often’. Alongside love, Don Bosco stressed the importance of reason and religion. His educational method was largely developed through reflection upon his own experience and disseminated through letters, talks and example.

Don Bosco also founded the Salesian Society – now the third-largest Catholic religious order in the world – in 1859. The Society was named after St. Francis de Sales who was known for his kindness and gentleness, a trait which Don Bosco wanted his Salesians to acquire. In Britain they have focused on the provision of Catholic secondary schools initially for ‘the aspiring working class’, homes and residential schools for children at risk, and more recently local community projects and retreats.

Walk eastwards along Paradise Street and then take the path directly ahead through King’s Steps Gardens. At the far end, walk carry on walking along the path between the flats and houses until you come to Mary Church Street. The Ship public house should be to your left. Our next stop is to the right on the opposite side of the road through a wrought-iron gateway.

Time and Talents