One of the most ‘able, wise and sympathetic educationalists of her generation’, Josephine Macalister Brew made a profound contribution to the development of thinking about, and practice of, youth work and informal education.

contents: introduction · life · in the service of youth · informal education · innovations in practice · youth and youth groups · final days · references · articles and links

Picture: Brew’s memorial window at Avon Tyrell. Designed and made by Stella Gross

Introduction

Josephine Macalister Brew (1904 – 1957) was an accomplished and innovative educator, whose ‘service to the young was unequalled in her generation’ (Woods 1957). She wrote not just one, but three classic books: In the Service of Youth (1943); Informal Education. Adventures and reflections (1946) – the first full-length exploration of the subject; and Youth and Youth Groups (1957). The last started as a rewrite of the first but ended up a completely different book, ‘because we live in a different world’ (Brew 1957: 11). She had an extraordinary ability to connect with people through her writing and speaking. She was also associated with several significant innovations in practice, including the growing interest in social group work in the UK; the development of ‘residentials’ as an educational form; and the formulation of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award (she wrote much of the programme for young women).

Life

Born on February 18, 1904, in Llanelli, Carmarthenshire – then known officially as Llanelly – she was registered as Mary Winifred Brew. The first months of her life were spent in a house on Park Terrace (this may be Bigyn Park Terrace or Park View Terrace in Llanelli). Mary Winifred was the eldest of three sisters (the other two being Margaret and Betty). Her father, Frederick Charles Brew, is listed as a boot salesman on her birth certificate – although later there was talk of his being in the army. Her mother, Elizabeth/Lizzie (Rees), had grown up in Llanelli, and Elizabeth’s father (Robert Rees) appears to have been a stonemason and contractor. He is listed as deceased on the wedding certificate. Looking at the date of the wedding, it may have been arranged fairly quickly (Lizzie was two months pregnant). The couple was married from Park Terrace. Previously, Lizzie had been living a few minutes away in Park Street with her mother (Margaret Rees), according to the 1901 Census.

The Brew family appears to have moved several times while the three girls were growing up. For example, in 1911, they were living on the High Street in Newport, where her father was listed as a manager of a shoe shop. Mary Winifred had been enrolled at St Woolos (Infants) School, Newport, a couple of years earlier (National School Admission Registers and Log Books). It was just a short walk from home. In 1921, they were based in the Rhymney Valley in Ystrad Mynach. Her father was now listed as a Boots (the chemist) Retail Manager. It looks like the family lived over the shop on Bedwlwyn Road. It is still a pharmacy.

Brew went to the University of Wales at Aberystwyth and graduated in 1925 with a lower second in history. She entered teaching, becoming a history mistress at Shaftesbury High School for Girls, Dorset. According to one of her colleagues (Gladys Gildersleve Powell), she was a born teacher, but not a teacher in a girls’ high school! She looked to the possibilities of the different areas of school life, for example, writing and helping to produce a play for the young women. By this time, she was known as ‘Jo’. In 1932, she decided to leave the school and live with her mother in Cardiff (her father had died in 1928 in Merthyr Tydfil). She took up writing for local papers and studied to attain her Doctor of Law. (Graduates of the University of Wales could obtain the LL.D. by the submission of a thesis around a particular aspect of law). It was at this time that she became involved as a worker in youth projects.

Youth work in Cardiff, Lincoln and beyond

Josephine Macalister Brew’s first encounters with the work had been in Tiger Bay (Butetown) in Cardiff.

My first introduction to club work at a very tender age was to be sent to a club in one of our most notorious docklands. I was welcomed, if you could call it that, by a harassed leader who hustled me into a roomful of girls, most of them seventeen-year old girls from dressmakers’ and tailors’ sweat-shops-but of course I did not have even that crumb of information then! ‘Well, girls,’ said the ‘bright’ leader, ‘here is little Miss – who is going to play you some lovely music.’ She then turned to me, and said, ‘I’m sorry, but the girl who usually plays for dancing isn’t here tonight. I’ll come back and do what I can for you later.’ That was the last I saw of her until she came back to tell us that the club was closing. In my more cheerful moments I attribute the fact that the class survived the evening to qualities I share with Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, but in moments of grim truthfulness I realize that it was just luck and the fact that even the adolescent shrinks from practising cruelties on the very young and innocent! This may be, one hopes it is, a rare introduction to club work. (Brew 1943: 82-3; 1957: 190)

Just when this introduction took place is unknown, and it may have been some time before she was recorded as being involved in work with the Butetown Women’s and Girls Club (Western Mail and South Wales News 1935). She was also, it appears, connected to the South Wales educational settlements. There were a number close to where she or her family lived (e.g. Merthyr Settlement, Bargoed and Rhymney Valley Educational Settlement, the Brynmawr Experiment (near Ebbw Vale) and Maes Yr Haf Educational Settlement, Cardiff). These projects were part of an initiative undertaken by the Society of Friends (Quakers) and drew on the experience of adult schools and other educational settlements such as Woodbrooke, Fircroft and Swarthmore. Strong links were also made with University College, Cardiff, the WEA and with local leaders such as teachers (see Jones 1985). Significantly, with the involvement of people like A. D. Lindsay (then Master of Balliol) and Tom Jones (Secretary to the Cabinet), a coherent philosophy was developed, and resources followed. Perhaps the most interesting of the nine settlements established were those pioneered by William Noble and Emma Noble in the Rhondda Valleys (at Maes-yr-Haf from 1927 onwards), and Peter Scott’s Brynmawr Experiment (near Ebbw Vale) (see Freeman 2004 for an overview of educational settlements).

Some of the themes that emerged in Josephine Brew’s later work can certainly be found running through the activities of these settlements. They were characterised by a focus on democratic control, self-help and cooperative ventures, and a belief in the power of community-based education to change society. ‘The principle was always to try to remove the taint of charity by involving local people in practical ways and by developing their skills for the benefit of the community, and to offer educational opportunity as a means of growth’ (Jones 1985: 94). A special emphasis was placed on self-governing clubs, often with club-houses built by members. In the Rhondda Valley, there were 52 clubs with a membership of 9,000 men, women and young people that provided ‘warmth, workshop equipment and a chance for people to develop latent abilities (Pitt 1985). Girls and boys clubs also formed a significant part of a number of the settlements. In addition, there was a strong emphasis on local investigation and community study, probably the best known being Jennings’ (1936) study of Brynmawr (see also, Pitt 1985 for a discussion of the Brynmawr experiment).

In 1936/7 Brew took up an appointment as the youth officer for Lincoln – one of the first local education authority-funded youth work posts. She also became the Secretary of the Lincoln Federation of Girls Clubs. (The ‘Macalister’ had appeared by this point – from where I do not know!). Jo’s mother moved up with her from Cardiff, and they found a house about a mile from Lincoln Cathedral on Roseberry Avenue overlooking West Common.

In Lincoln, Brew was involved in several different initiatives, including work around community centres and the development of a club for barge children. The latter was located in basic premises but was run with the philosophy that it was very much a member’s club. Brew had the principle that if you break a window, it will stay broken until you mend it; if you muck up a wall, it will stay like that until you paint it (conversation with Gladys Gildersleve Powell).

Through the Federation, she became involved with the National Association of Girls Clubs – serving on the Executive Committee, and speaking at the Secretaries’ Conference. She was reported as a funny, lively and often provocative speaker. This is a short report from the Standard, the local Lincoln paper from back in 1938:

What is Social Service?

What is social service? Miss J. Macalister Brew, secretary of Lincoln Juvenile Organisations Committee (JOC) told an audience that many people had a wrong idea of it.

They thought it involved people going round doing good to other people, but it was not. It was a “group of people going round having fun with other people.”

Miss Brew spoke of the great need for young business men to take an active part to arrange darts’ matches, to play the piano, and to arrange debates.

She amused people when she said she was prepared to give a substantial prize to anyone who could give her something she could not use for the clubs.

I can use anything from silk stockings to a luxury radiogram, she declared.

Miss Brew concluded her report with an ultra-short fairy story—“There was once a J.O.C. secretary who did not finish her speech by appealing for members.”

With the outbreak of the Second World War, there was considerable disruption to the work of the Association, followed by demands that it develop its services. Given the widespread interest in the launching of the ‘Service for Youth’, there was a need to help ‘those who have been called upon at very short notice and often with little preparation and experience to deal with new clubs, youth centres and the like’ (Brew 1940: 10). Jo was asked to edit several existing pamphlets into a book, the first under her name, which appeared in 1940: Clubs and Club Making.

Josephine Macalister Brew was also called upon to give talks in various places, and quite a number of these were reported in local and regional papers. She was making frequent trips to Scotland, Wales and across England. A number of these talks were later to appear in chapter form in In the Service of Youth (1943).

Brew moved to Oldham to be the Youth Officer there. Her mother stayed in Lincoln for a time, with her daughter Elizabeth, who was a nurse, joining her. The stay in Oldham was relatively brief for Jo as she was encouraged to join the staff of the National Association of Girls Clubs (by Eileen Younghusband, among others). She was appointed Education Secretary on June 1, 1942 (one of the other candidates for the job was Pearl Jephcott, who was, at the time, working for the Association as a temporary national organiser).

London and the National Association of Girls and Mixed Clubs

At NAGMC, Brew was to join a very talented group of women, including Eileen Younghusband (who was later to write several seminal books and reports in social work); Madeline Rooff (author of Youth and Leisure 1935); and Pearl Jephcott, who wrote a series of important books on the lives of young people 1942; 1948; 1954; 1967). Her work also brought her into contact with key figures around the education world such as Sir John Wolfenden, later to become vice-chancellor of the University of Reading and chair of several royal commissions; Henry Morris the pioneer of village colleges, and S. H. Woods (an influential senior official in the Board of Education who became a friend, and who chaired her committee at NAMC&GC).

The Association’s offices moved several times. For a time, they rented part of Hamilton House, Bidborough Street, London WC1 (sharing with the National Union of Teachers) – and Brew had a flat close by at 5 Grafton Chambers (it was also just a few steps from Euston Station). Later, when the Association moved to Devonshire Street, there was a little further to go to the office. The people she worked alongside talk of her with great affection. Jo was friendly – not at all ‘stuck-up’ – committed and talented. Much of her writing was done at a small desk in Grafton Chambers and later in the cottage at Wanstead. Gladys Gildersleve Powell, who was later to share the flat and cottage with her, talks about her living on a diet of black tea and cigarettes. She could never persuade her to eat proper food. As Brew wrote, beside her would be a teapot full of stewed tea and a big ashtray full of cigarette ends.

If all this activity wasn’t enough, Brew was also approached to write for a new and influential BBC radio series (To Start You Talking) aimed at young people. It ran from Autumn 1943 to Spring 1944. Her research involved hanging about in pubs, cafes and other places where young people gathered. Wearing a headscarf and a dirty old macintosh, she would observe and listen to their conversations. Young people were then invited to the studio to talk about the different themes raised (Alan Dein discusses this pathbreaking series in an Archive on 4 programme – The First Generation X; see also, Madge et. al. 1945). These programmes were, as the title suggests, designed as starters for discussion. Aimed at and involving young people, their directness and freshness proved to be very popular. As Charles Madge (1945: 2) commented, ‘Here was something remarkable. Something new in radio technique, and new also as a form of social documentation’. Jo did not appear on the programme but is acknowledged in several scripts as the writer of the ‘dramatic interlude’ that usually began the programme. The producers apparently said she had the wrong kind of voice, which she rather resented. As a speaker, Brew could hold large audiences in her hand. Her voice was ‘light’ and it could be considered upper-class. However, as Gladys Gildersleve Powell commented, ‘it could also be of no class at all’.

As well as being a period of significant change in her public life, there appears to have been major changes in her private life. Josephine Macalister Brew had met and seemingly married Robin Keene. It was a relationship that did not last long, as it seems he was killed either during the war or soon after (although I have not been able to find either a marriage certificate or a death certificate). Jo talked little about her husband to colleagues like Vera Mulligan (her secretary for much of the war). Gladys Gildersleve Powell – who was then a lecturer at Swansea Training College and rarely in London – never met Robin Keene. She did, however, talk of a time when she and Jo met at Paddington and Jo told her, ‘I’m going to do it’. Brew ‘never used his name and never referred to her marriage. It is a sort of empty space as it were’ (Gladys Gildersleve Powell).

Her career as a writer had taken off, with various articles appearing in the Times Educational Supplement concerning the needs of young people, and provision for them. The first few years spent at what became the National Association of Girls Clubs and Mixed Clubs (then Mixed Clubs and Girls Clubs) also produced two remarkable books: In the Service of Youth (1943) – which is, in effect, the first full statement of ‘modern’ youth work; and Informal Education (1946), the first single-authored book on the subject. Brew also left us with an array of shorter pieces from this period, for example, in the various publications and magazines produced by the National Association of Girls and Mixed Clubs and in the Times Educational Supplement.

In the Service of Youth

Brew’s books display her originality as an educational thinker. While her focus was on young people, she located what she was doing within a view of education that was lifelong. She also recognised the possibilities of learning in social life. In the Service of Youth, while a product of its time, is the first comprehensive statement of the principles and practice of ‘modern’ youth work (Smith 1991: 36 – 39). Indeed, it was one of the first books to discuss ‘youth work’ rather than ‘boys’ work’ or ‘girls’ work’.

The book argued for:

- A commitment to community, citizenship and co-operation. The central vehicle for realising this being the voluntary association of members – the club. Brew saw in the ‘club’ a means by which people could freely identify with one another and gain the skills, disposition and knowledge necessary for citizenship.

- A clear focus on process. One of the striking features of Brew’s writing is the attention she gives to the way things are done and what can be learnt from the process. ‘A youth leader must try not to be too concerned about results, and at all costs not to be over-anxious’ (1957: 183), she was later to write.

Only by the slow and tactful method of inserting yourself unassumingly into the life of the club, not by talking to your club members, but by hanging about and learning from their conversation and occasionally, very occasionally, giving it that twist which leads it to your goal, is it possible to open up a new avenue of thought to them (1943: 16).

- A recognition of the social and emotional needs of young people. Brew was a great reader of psychology texts – and she was well aware of the sea change in understandings of emotional, moral, intellectual and sexual development and the subconscious that had occurred. She displays both a belief in young people’s abilities to work things out for themselves and a concern that workers should not be neutral bystanders in this process.

- A championing of popular culture as a site for intervention. Brew displayed an engaging determination to work with the things that young people themselves value. But Brew was concerned to do more than start from where young people are, she did not want to rate activities on some bourgeois notion of value: ‘True culture is the appreciation of everything, from a plate of fish and chips to a Van Gogh… We must give our young club members a vision, but it must come by way of co-operation through appreciation to creation’ (1943: 15).

- A recognition of the economic and social context in which work takes place. As with many others within the girls’ club movement, Brew attended to the economic and social conditions that young people experience. ‘No club on earth will succeed with a programme which bears no relation to the industry, working conditions and economic and social background of the area which it serves’ (1943: 69).

A sixth element is also discernible in the book – that of youth work as a pioneering form of informal education (1943: 173-4) – but more of that is below.

Previous writers had, of course, addressed a number of these concerns. What made In the Service of Youth special was that Brew managed to bring these elements into a reasonably consistent relationship. She also grounds this in the daily realities of practice. Much of the significance of this book lies not so much in what is said, but in the way things are put. Her tone of voice and her descriptions of practice and individuals communicate much about her view of relationships between workers and young people. It also points toward where workers should focus their efforts. Her attention to form and process in her writing mirrors that which she expects in workers.

Looking back, we can develop a critique along several fronts. Brew did not have the political edge or analysis of the early feminist youth workers. While she was concerned with citizenship and community, her focus tended to be somewhat individualistic. In the end, she did not escape her class location. Nor would she have wanted to. There are residual elements which today be seen as patronising. However, we should take great care not to decontextualise her analysis. What we can see reflected in her writing formed much of the foundation for what was to come in the 1960s (Smith 1991).

Informal Education

Informal Education begins by setting out two contrasting methods of the educational approach. The first involved ‘serious study’ through schools, university extension classes and organisations such as the WEA. The second entailed ‘active participation in a variety of social units’ (1946: 22). It is the latter with which she is particularly concerned. She argued that education should be taken ‘to the places where people already congregate, to the public house, the licensed club, the dance hall, the library, the places where people feel at home’ (op. cit.). Much of the book is then explores how educators can ‘insert’ education into such units. In particular, she focuses on what we might describe now as the process of creating and exploiting teaching moments.

Again, it was not the individual elements of her approach that were new. Previous generations of educators had recognised each. Rather, it was the way she brought these together in a persuasive and accessible way. Here, I want to note five key elements.

- Our concern should be with the cultivation of the ‘educated man’. The focus of the work, according to Brew, should be people’s struggle to gain ‘the equipment necessary for the great adventure of living the life of an educated man’ (1946: 375). She suggests that probably the best definition of the educated man is that ‘he is capable of entertaining himself, capable of entertaining a stranger, and capable of entertaining a new idea’ (ibid.: 28).

- Every human activity has within it an educational value (1946: 27). Brew recognised that the requirement for continuing education could only be met if attention was paid to experiences, events and settings of everyday life. In Informal Education, she explored the educational opportunities that lie in different areas of endeavour. The book is structured around different arenas or approaches where these moments can occur: through the stomach, the feet, the work of the hands, the eyes, the feelings, and through the ears.

- Work with people’s interests and enthusiasms, and, if possible, address issues quickly and on the spot. ‘An activity which is so deeply rooted in the hearts of people is obviously a grand jumping-off point for educational programmes’, Brew (1946: 96) wrote. She argued that often what people need most is encouragement and that the responses that educators make need to be unhooked from the notion of ‘subject’, ‘course’ and ‘syllabus’. Much educational opportunity is lost because of a desire to encourage people to join classes, she (1946: 32) suggested. Things need to be kept simple and entertaining.

- Harness the power of association. Brew talked of the power of activities such as sports to deepen civic consciousness and of the need to link informal education with such interests, along with ‘home interests’ such as parent education, and education in other groups and associations. She had no wish to turn every association into a solemn conclave for “uplift”’, but recognised that there were considerable possibilities for learning in them (1946: 42).

- Informal educators need to have a wide cultural background and be lively-minded. They must be able to engage with themselves, others and ideas, and foster environments where people know belonging and learning. The standards that Brew sets for informal educators are high. Informal educators have to ‘educate’ themselves (see above), be ‘lively-minded, if unconventional’, able to relate to people, and flexible in approach.

At the time of publication, the book was well received. As Houle (1992: 285) has subsequently noted, ‘beneath its lively and anecdotal surface, the book makes some excellent methodological points’. For many people involved in youth work, it provided a way of making sense of, and developing their practice. One criticism that can be made of the book is that it does not draw upon an explicit or fully worked-through theoretical framework. framework. Her work does not directly address and develop the already rich tradition of thinking about ‘informal’ education. If she had made connections with the work of Dewey, Lindeman, Yeaxlee and others, then the book would have been even more powerful in its impact. This is not to say that Brew does not have a framework, but it does take some work to identify it.

Perhaps the main central question that lies over the book concerns her understanding of the notion of informal education. Is it the process of stimulating reflection and active participation, or is it, more narrowly, the insertion of teaching into different social situations? Brew would probably have argued that it is the former, but that there is a great danger that informal educators will neglect the need for teaching moments and organised programmes and sessions. In some ways, such criticism is churlish. Brew had made a formidable contribution. Informal Education is a landmark book. It is the first book-length exploration of this area of educational practice (Houle 1992; Smith 2000).

Innovations in practice

In the later part of the war and after, Brew was much in demand as a writer, an expert on youth work, and as a speaker. Jo may have been small, but she cut a flamboyant figure. With platinum blonde hair, colourful and fashionable clothing, and a certain energy, there are various stories of the attention she attracted. She became a member of the Central Advisory Council (England) of the Ministry of Education and also of bodies connected with the Ministry of Labour and the Colonial Office. As a speaker, Brew had that rare ability to connect with an audience, large or small, and to hold it in the palm of her hand. She continued to write for educational journals, but also augmented these with pieces for national papers such as the Daily Mail and the News of the World. Indeed, writing for the latter enabled her to buy some much-needed furniture when she and Gladys moved from central London.

As the Education and Training Adviser to the National Association of Mixed Clubs and Girls Clubs, she not only designed the Association’s training schemes for club leaders and members but was also the founder and director of the Association’s ‘residential courses for girls working in industry and commerce’. It is this latter area of work, along with her championship of mixed clubs, her involvement in the promotion of group work, and her work on the Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme, that mark out her enduring contribution to the field post-Informal Education. She was also involved with the Rank Organisation – sitting on a panel that advised J. Arthur Rank about films being made for children.

Mixing. Brew, along with many other staff members at NAMCGC, was a strong advocate of mixed work: ‘Our business is not with the encouragement of boys’ clubs, or girls’ clubs, but with the welfare of boys and girls, and this welfare is surely best served by the mixed club’ (1943: 56). She talked of those who opposed mixing as being either lazy or fearful and argued that mixed clubs and groups, properly led, contributed to the building of healthy relationships between young women and young men (1957: 151-57). Brew argued that boys and girls brought ‘different gifts to the enrichment of club life’ and that mixing did not imply homogenisation but rather the fostering of differing identities (1957: 155-56). She very clearly saw that young men and young women required different opportunities – and that there was a case for some forms of separate provision (see below). As can be imagined, mixing was not popular within the boys’ clubs movement and, in particular, with Basil Henriques (1933; 1937). Brew and Henriques had various ups and downs – and a ‘set to’ on television (Gladys Gildersleve Powell).

The Girls in Industry Programme. Once unfairly described as the ‘poor girls finishing school’ (see Allcock 1988: 23), these NAMCGC courses designed and run by Brew were targeted at young women working in industry and commerce. Young women were released and usually paid for by their employers to undertake one of the courses. Based around a residential experience – usually at one of the Association’s centres such as Avon Tyrell – the courses used almost stereotypical ‘girls’ interests’ such as homemaking, fashion and beauty and sought to open new vistas. As one person who worked on these programmes put it, Brew wanted to encourage ‘adventures of the mind’. The courses, which began in 1952, were innovative and proved to be very popular with their participants. They continued well into the 1970s at NAYC as ‘Macalister Brew Courses’.

Group work. Brew was part of the movement to popularise social group work in Britain. She was a member of the group chaired by Peter Kuestler that produced ‘a first contribution to the literature of social group work in Britain’ (Kuenstler 1955: 7). In the Service of Youth and Informal Education explored in different ways, ‘the fascinating possibilities of “education through the group”’ (Brew 1955: 89). She now bemoaned the tendency in youth work to pay too much attention to individuals rather than groups, and the extent to which group work among adolescents is regarded as a social palliative, rather than as ‘a new and exciting form of informal education (op. cit.).

The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme. The idea of a nationwide scheme of awards for young people grew out of an initiative by the Duke of Edinburgh in 1955 (the scheme itself was announced in 1956) (Wainwright 1966: 89). From the start, it was assumed that the Girls’ Award would be different from the Boys’. Brew was approached to chair a drafting committee to prepare the syllabus. What emerged, in particular, was a section, ‘Design for Living’, with an emphasis on ‘home-making’. Unfortunately, as with the Girls in Industry Courses, it was too easy for this to be interpreted in a rather domesticating way by those running the scheme. Dick Allcock described her vision as ‘very much to do with giving girls the time, space and skills to make the best of themselves. Those who interpreted this narrowly in terms of face, fashion and food missed the point, which was to aim for a broader, deeper expression of womanhood in every respect’ (1988: 24). The pilot Girls’ Award scheme was launched in 1958.

Youth and Youth Groups

While working on the new Award scheme, Brew was also writing Youth and Youth Groups (1957). She begins:

This book has been written almost by accident. The original intention had been to revise and bring up-to-date In the Service of Youth which was published in 1943. But it could not be done, for the latter was written in the war years and since then we have moved into an uneasy peace and the age of automation. In the intervening years there has been much social legislation, and it would be surprising if an era which had seen the birth of a Welfare State and full employment had not had far-reaching effects on the problems and attitudes of adolescents and, therefore, on the service designed for their well-being….

Achievement and frustration, failure and fulfilment, have been the lot of all those who have laboured ‘in the service of youth’, in those arduous years. (1957: 11)

Given her interest in informal education and group work, change was not surprising. She believed that the ‘most interesting and promising development in educational theory in fifty years’ had taken place in nursery schooling and youth work. There was within the latter, she argued, an ‘unresolved conflict between those who still regard the work as a social palliative and those who regard it as a new and exciting form of informal education’ (1957: 100). Alongside this there had also been a growing appreciation of the nature and power of group experience, and how learning can be facilitated within groups.

In the skillfully constructed group people after their schooldays can become better acquainted with the basic processes of social life, cooperation and mutual help. It is in these groups that they can learn the social attitudes of sympathy, kindness of brotherly love. (1957: 101)

Brew goes on to argue that it was in the area of the promotion of healthy relationships that youth groups had the most to offer to the well-being of communities: ‘[T]he revitalized youth group, far from being an anachronism, can have a very important part to play in the general education of many young people for whom the continuing school pattern is not psychologically satisfying’ (Brew 1957: 103). The interest in democratic living and association remained, but the needs of young people became more clearly articulated. The book’s organisation made them the starting point for the work. Classically, she warns us against expecting results.

We are dealing with the most mercurial quality in the world, the adventurous yet timid, changeable yet loyal, earnest yet frivolous adolescent human being. Often these young people have passed out of the group long before the effect of their membership will be apparent to them or others. (1957: 114)

She also counsels us against underestimating the intelligence of young people – their ‘keenness to use their minds as well as their bodies’.

We tend constantly to water down the milk of education when what is really needed is that it should be presented in a vessel of a different shape, in the adult cup instead of the infant’s feeding bottle. (1957: 213)

Three years later, the Albemarle Report was published – and the landscape of youth work began to change again. A new edition of the book – revised by Joan E. Matthews – appeared in 1968, but it was now faced with a growing focus on social education, the growth of state-defined practice, and, a little later, the raising of the school-leaving age. A new generation of writers had appeared with a changed vocabulary. In the process, Josephine Macalister Brew received less or little attention in training for, and debates about, youth work. It had to wait for another generation of commentators to rediscover her significance and re-embrace informal education.

The final days

In the early 1950s, Josephine Macalister Brew and Gladys Gildersleve Powell moved out of the flat in Grafton Chambers to a cottage in Epping Forest (Forest Cottage, Oak Hill, Woodford Green). It is pictured in the memorial window at the start of this article (upper left) along with their cat, Minnie. While the setting was peaceful, Jo continued to work at the same demanding pace.

People used to say isn’t she wonderful, but they never knew what it cost her. Before she made these public addresses she was sick as anything. There was a tremendous physical cost. The work was burning her out. A frail body, never strong. When she went into action, it was as it were, it was as if a light came on, and afterwards nothing. It is difficult to use the word genius – but she had this extra quality, this something. (Gladys Gildersleve Powell)

She did relax and would go to the theatre, which she loved, but also experienced ‘moods of depression, but would snap out of them quickly’ (op. cit.).

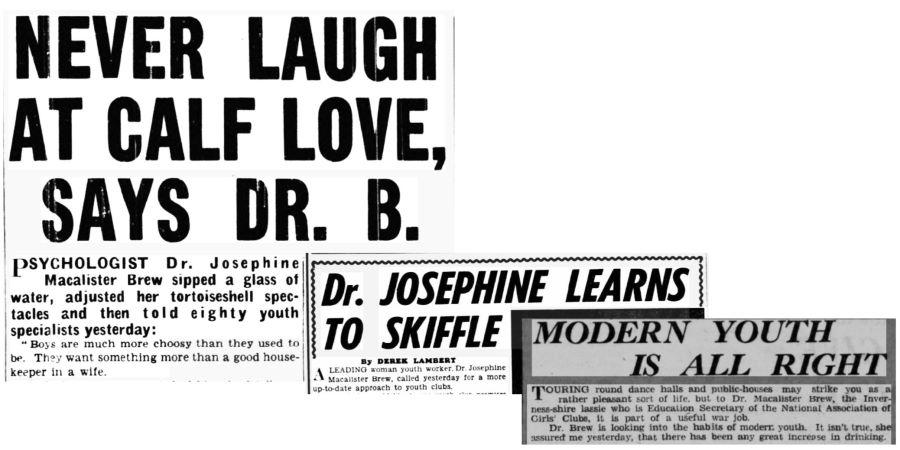

Josephine Macalister Brew had also become something of a public figure with profiles in national papers like The Sketch and stories in tabloids like The Mirror and Daily Record.

The Mirror 1949 and 1956 . Daily Record 1942

John Wolfenden later (1957) commented, ‘her unorthodox methods and rather unusual appearance sometimes frightened, even alarmed, the traditionalists’. One of the interesting features of the reporting is the different labels attached to her. She was variously described as a psychologist (Daily Mirror, May 31, 1949), an educationalist (Daily Herald May 31, 1949), ‘a very determined hider of lights under bushels (The Sketch October 21, 1953), a legal expert and psychologist (Fifeshire Advertiser February 19, 1955) and an ‘Invernesshire lassie’ (Daily Record October 17, 1942). Most of these things were true. She had gained a doctorate in law, was indeed an educationalist, and very well-read in psychology. Just where the ‘Invernesshire lassie’ came from, I have no idea.

Not long after Easter in 1957, Jo had been very sick on a flight to Northern Ireland. She had not been well for a time and had put off going to the doctor. This convinced her. She was quickly referred to a specialist who admitted her straight to the Jubilee Hospital in Woodford. Told she had a stomach ulcer, and although she feared worse, she knew she required an operation. Jo worked on the foreword to the Award scheme in the short time she was waiting in hospital for her operation. She had also just learnt that she had been awarded a CBE.

Josephine Macalister Brew died in the local cottage hospital on May 13, 1957. The specialist knew before the operation that what he was looking at was cancer – but he didn’t want Brew to know. In the end, there was little that could be done. Over the years, she had often been ‘under the weather’ and suffered from a bad chest from her constant smoking. Her GP, Dr Challis, was a little annoyed at the result of the autopsy. Although she had been warning Jo about her smoking, her lungs were quite untouched. Jo’s death was due to cancer of the stomach and of her liver (conversation with Gladys Gildersleve Powell).

There was a private funeral at the West London Crematorium at Wanstead. Jo was remembered in a memorial service at the St Marylebone Parish Church on June 14, 1957 (which was close by the headquarters of the National Association of Mixed Clubs and Girls Clubs). Vera Mulligan was commissioned to create a stained glass window for Avon Tyrell to commemorate her work [and is pictured at the start of this article]. Her ashes were scattered in the back garden of Forest Cottage by Gladys Gildersleve Powell and Mrs Low (who lived close by and helped with cleaning the cottage).

One of Brew’s favourite texts was ‘I have come to you and you will have life’ – and life is exactly what she had and gave. John Wolfenden (1957) commented, ‘There can be few people who have lived life so fully, so usefully, or so serviceably… It was not surprising that she was worked to death’. Josephine Macalister Brew wasn’t just one of the most able, wise and sympathetic educationalists of her generation; she made a profound contribution to the development of thinking about, and practice of, youth work, and informal education generally.

____

The opening image of the memorial window at Avon Tyrell shows Forest Cottage – where Josephine Macalister Brew lived – on the left. Towards the bottom (and the right) is Minnie the cat.

References

Allcock, D. (1988). Development Training. A personal view. Stoneleigh: The Arthur Rank Centre.

Armson, A. & Turnbull, S. (1944). Reckoning With Youth. London: Unwin and Allen.

Brew, J. Macalister (1940). Clubs and Club Making. London: University of London Press/National Association of Girls’ Clubs.

Brew, J. Macalister (1943). In The Service of Youth. A practical manual of work among adolescents. London: Faber.

Brew, J. Macalister (1945). ‘Only one living room’, ‘When should we be treated as grown-ups?’, ‘All out for a good time’ – dramatic interludes in C. Madge et al To Start You Talking. An experiment in broadcasting. London: Pilot Press.

Brew, J. Macalister (1946). Informal Education. Adventures and reflections. London: Faber.

Brew, J. Macalister (1947). Girls’ Interests. London: National Association of Girls’ Clubs and Mixed Clubs.

Brew, J. Macalister (1949). Hours away from Work. London: National Association of Girls’ Clubs and Mixed Clubs.

Brew, J. Macalister (1950). ‘With young people’ in the Bureau of Current Affairs Discussion Method. London: Bureau of Current Affairs.

Brew, J. Macalister (1955). Group work with adolescents in P. Kuenstler (ed.). Social Group Work in Great Britain. London: Faber & Faber.

Brew, J. Macalister (1957). Youth and Youth Groups. London: Faber & Faber.

Brew, J. Macalister (1968). Youth and Youth Groups 2nd. edn. Revised by J. Matthews. London: Faber & Faber.

Coyle, G. (1947). Group Experience and Democratic Values. New York: Women’s Press.

Coyle, G. (1948). Group Work with American Youth. New York: Harper.

Davies, B. (1999). From Voluntaryism to Welfare State. A History of the Youth Service in England Volume 1: 1939 – 1979. Leicester: Youth Work Press.

Dein, A. (2014). The First Generation X. Archive on 4. London: BBC Radio. [https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b03wgt9r. Retrieved April 17, 2024].

Edwards-Rees, D. (1943). The Service of Youth Book. Wallington: Religious Education Press.

Freeman, M. (2004). ‘Educational settlements’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/welcome/educational-settlements/. Retrieved June 8, 2004]

Henriques, B. (1933). Club Leadership.

Henriques, B. (1937). The Indiscretions of a Warden.

Homans, G. (1951). The Human Group. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Houle, C. (1992). The Literature of Adult Education. A Bibliographic Essay. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Jeffs, T. (1979). Young People and the Youth Service. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Jeffs, T. & Smith, M. (eds.). (1990). Using Informal Education. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Jennings, H. (1936). Brynmawr: A study of a distressed area based on the results of the social survey carried out by the Brynmawr community study council. London: Allenson & Co.

Jephcott, A. P. (1942). Girls Growing Up. London: Faber & Faber.

Jephcott, A. P. (1943). Clubs for Girls. Notes for new helpers at clubs. London: Faber & Faber.

Jephcott, A. P. (1948). Rising Twenty. London: Faber & Faber.

Jephcott, A. P. (1954). Some Young People. A study of adolescent boys and girls. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Jephcott, A. P. (1967). A Time of One’s Own. Leisure and young people. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

Jones, E. (1985). Education as a response to social stress. The South Wales educational settlements in R. Cann, R. Haughton and N. Melville (eds.) Adult Options. Three million opportunities. Goudhurst: Weavers Press/Educational Centres Association.

Kuenstler, P. (ed.).(1954). Youth Work in England. London: University of London Press.

Kuenstler, P. (ed.).(1955). Social Group Work in Britain, London: Faber and Faber.

Madge, C., Coyish, A. W., Dixon, G. and Madge, I. (1945). To Start You Talking. An experiment in broadcasting. London: Pilot Press.

Ministry of Education (1945). The Purpose and Content of the Youth Service. A report of the Youth Advisory Council appointed by the Minister of Education in 1943. London: HMSO.

Montagu, L. (1904). The girl in the background in E. J. Urwick (ed.).Studies of Boy Life in Our Cities. London: Dent.

Pethick, E. (1898). Working Girl’s Clubs in W. Reason (ed.) University and Social Settlements. London: Methuen.

Piaget, J. (1932). The Moral Judgment of the Child. New York: Harper and Row.

Pitt, M. R. (1985). Our Unemployed. Can the past teach the present? Work done with the unemployed in the 1920s and 1930s. London: M. R. Pitt/Friends Book Centre.

Russell, C. & Rigby, L. (1908). Working Lads’ Clubs. London: Macmillan.

Smith, M. (1988). Developing Youth Work. Informal education, mutual aid and popular practice. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Smith, M. (1991). Classic texts revisited: In the Service of Youth, Youth and Policy 34: 36-39. [ https://www.youthandpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/y-and-p-34.pdf. Retrieved April 18, 2024].

Smith, M. K. (2000). Informal Education – Classic texts revisited, Youth and Policy 70, pp 78-90. [https://www.youthandpolicy.org/y-and-p-archive/issue-70/. Retrieved April 18, 2024].

Spencer, J. (1955). Historical development in P. Kuenstler (ed.) Social Group Work in Britain. London: Faber and Faber.

Wainwright, D. (1966). Youth in Action. The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme 1956 – 1966. London: Hutchinson.

Western Mail and South Wales News (1935). Flannel dance, Western Mail and South Wales News May 2.

Wheeler, O. (1945). The Adventure of Youth. London: University of London Press.

Wilson, G. and Ryland, G. (1949). Social Group Work Practice. Cambridge: Houghton Mifflin.

Wolfenden, J. (1957). Dr. Josephine Macalister Brew, C.B.E.. Nature 180, 68. [https://doi.org/10.1038/180068a0].

Woods, S. H. (1957). Josephine Macalister Brew, The Times May 31.

Young, A. F. and Ashton, E. T. (1956). British Social Work in the Nineteenth Century. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Articles and links

Josephine Macalister Brew – Why clubs at all? This 1943 piece written by Brew and others explores the rationale for youth club work.

Josephine Macalister Brew – Informal Education. Adventures and reflections can be borrowed from the Internet Archive.

Acknowledgements: I would like especially to thank Gladys Gildersleve Powell for sharing her memories of Josephine Macalister Brew. Vera Mulligan and Marjorie Smith also gave me some important insights into her character and work. Thanks also to Youth and Policy for allowing me to use material from articles (1991 and 2003) about Brew’s work, and to Catherine Kirkwood for digging out over 100 newspaper pieces about Brew. This 2024/5 version contains additional details of her work – particularly around To Start You Talking and Youth and Youth Groups, plus some further material from the 1997 interview with Gladys Gildersleve Powell.

To cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2025). Josephine Macalister Brew, youth work and informal education, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [ https://infed.org/dir/josephine-macalister-brew-and-informal-education/. Retrieved: insert date]

© Mark K. Smith 2001, 2020, 1925

updated: October 20, 2025