Chapter 1 of Mark Smith’s exploration of youth work and informal education – Creators not Consumers. Rediscovering social education (1982)

Just after club had finished Neil came into the office and asked if we could organise an ice skating trip. He thought we could easily fill a coach if we charged £1.50 per person. How did he arrive at £1.50 we asked? That’s what the British Legion had charged. How many people had he spoken to? About half a dozen. In the end it was agreed that he should take a list around next club night to gauge the response. He got 45 names and a delegation trouped in, would we now organise the coach and book the rink? You do it, we suggest, and after some discussion they go away and decide on a date and sort out ‘who is doing what’. Tony and Sue return, phone a bus company, and book a 42 seater. That’s three less seats than people who said they wanted to go, we say, and anyway where are we going to sit? People are bound to drop out comes the answer. They leave a scribbled note for the secretary to type in the morning. Meanwhile Neil is out canvassing the choice of rink. “Silver Blades” is the most popular so Tony and Sue do their bit again. What are you going to charge? They’d clean forgotten to ask the cost of the coach. Another phone ca/I and Mike (who was skilful with figures) produced the answer — £1.65 if we were going to allow a little leeway for those who didn’t turn up on the day and to give a tip to the driver. Mike took responsibility for the deposits, giving them to us to bank.

Youth workers are always booking coaches and organising trips, young people aren’t. It takes a lot of confidence, a fair bit of knowledge and quite complex skills to do what these young women and men did, yet they were all what could be called ‘low stream secondary modern’ and aged from 1 5 to 18 years. Take Neil for instance. When the workers first knew him he had considerable difficulties in relating to anyone in authority [page 6] and often to his peers. His frequent violent out-bursts and apparent concern only for his own feelings had gained him the reputation of being a “right bastard” and posed the workers problems. It had taken two years to establish a comfortable relationship between Neil and the workers and what was significant about his suggestion of an ice skating trip was not so much that he had made it, but that he had taken responsibility to do something about it. The workers had therefore been very keen to respond to his suggestion.

In this first chapter I want to look at two frameworks that can help us understand why organising a skating trip in this way can be seen as social education. These frameworks are:

- Youth work as process and product.

- Knowledge, feelings and skills as elements of a problem.

Product and Process

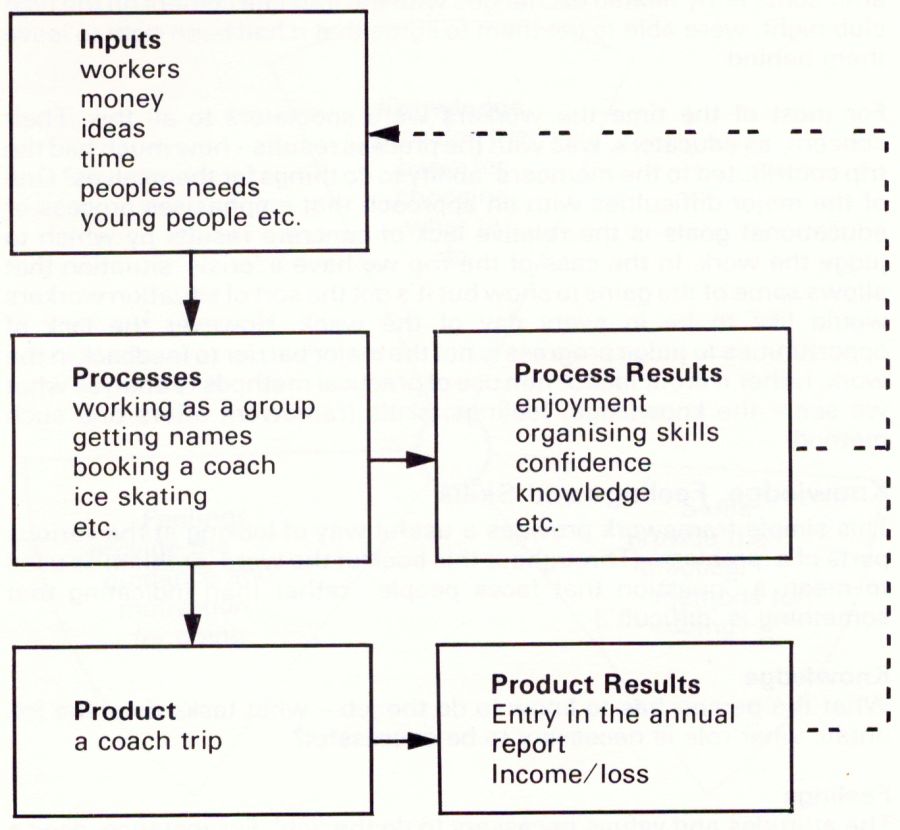

These workers wanted to build up people’s ability to do things for themselves. The way they went about doing this can be more clearly seen if we think of youth work as having processes and products. Processes are the way we use the different resources (or inputs) at our disposal. Products are the concrete events or things we create. Both products and processes have certain results. Thus we can show the ice skating trip in the form of the diagram. (See Figure 1.)

People put different emphasis on product and process. In general workers and administrators are keen on work that can be readily seen and counted. They are interested in concrete results from their efforts, such as the number of football teams a club fields, attendance on club nights or building usage.

Process results are far less tangible. They are to do with relationships, the strengthening of people’s competence and feelings. Both product and process results can feed back into the inputs. Thus a financial loss on an activity, (a product result), might mean there is less money available for other events or the development of people’s skills, (a process result), might mean a more involved ‘activity’ is possible.

If we return to the trip, the product result was an ice skating trip that in the end has 29 participants, a financial loss (£16) and left four members stranded in London when they did not turn up on time for the returning coach (the decision of the organisers). It is not an outcome that recommends itself to youth work administrators keen to justify their work by the usual standards. Some of the process (or educational) results can be seen when the members organised another trip – they [page 7] demanded larger deposits and increased the price. Nobody was late for the return journey!

Figure 1: Product and process in the skating trip

The decision to leave people behind marked an interesting stage in the group’s developing confidence and ability to weigh up alternatives. The factors they had taken into consideration included the coach driver’s impatience, the responsibility to return younger members home at a reasonable time, the ability of the late four to handle their predicament and the possible strains on friendships (one of the late four was the elder brother of one of the organisers!). Moments of crisis such as this are often one of the few opportunities youth workers have to see if people’s feelings and abilities have changed. A difficult decision or action has to be taken and the results lived with. In the event the ‘organisers’ came out [page 8] pretty well. They certainly increased in standing within the club and, after some fairly heated exchanges with the four late-comers on the next club night, were able to get them to agree that it had been right to leave them behind.

For most of the time the workers were spectators to all this. Their concern, as educators, was with the process results— how much had the trip contributed to the members’ ability to do things for themselves? One of the major difficulties with an approach that emphasizes process or educational goals is the relative lack of concrete results by which to judge the work. In the case of the trip we have a ‘crisis’ situation that allows some of the gains to show but it’s not the sort of situation workers would like to be in every day of the week. However the lack of opportunities to judge progress is not the major barrier to feedback in the work, rather it is our lack or non use of practical methods to analyse what we see — the knowledge, feelings, skills framework offers one such method.

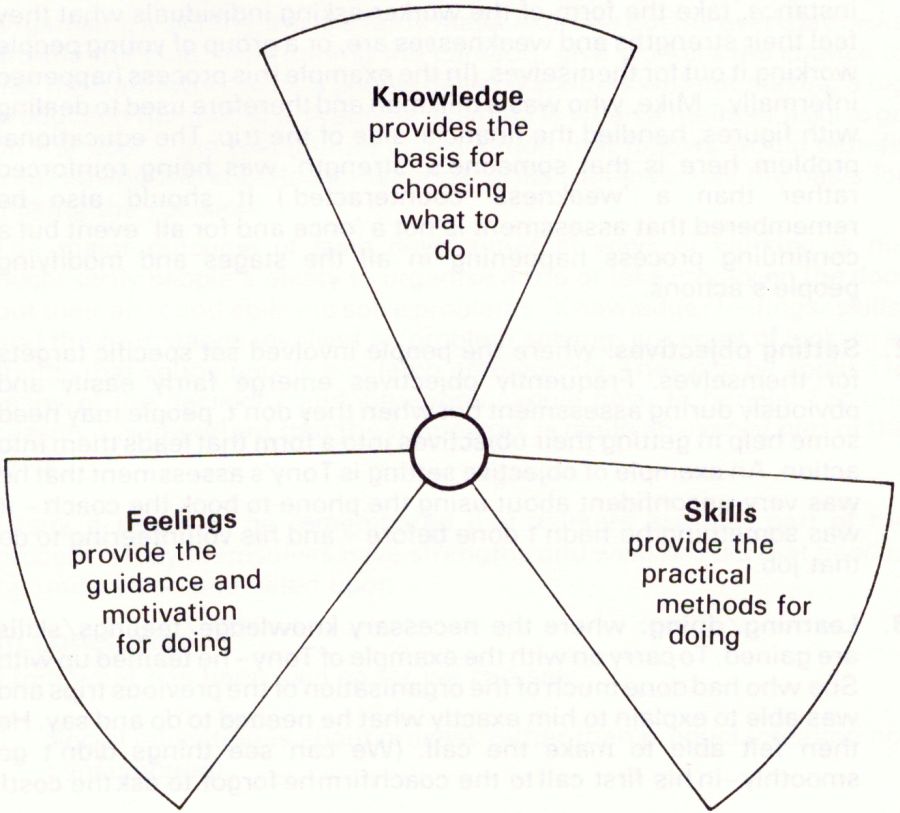

Knowledge, Feelings and Skills

This simple framework provides a useful way of looking at the various parts of ‘problem’. (Throughout this booklet the word ‘problem’ is used to mean a “question that faces people” rather than indicating that something is ‘difficult’.)

Knowledge: What the person has to know to do the job – what tasks does the job entail, what role is necessary to be successful?

Feelings: The attitudes and values necessary to do the ‘job’. For instance, does a particular ‘job’ mean the person has to tell the truth, remain calm, be cheerful, like people etc? How much confidence does the person require?

Skills: What the person has to be able to do to complete the job. This includes observational/informational skills, thinking skills, communication skills and action skills.

If we view the ice skating trip as a ‘problem’ to be solved we can see that certain requirements will have to be met:

Knowledge: The cost and availability of ice skating. Details of coach companies. What the demand is. Timing – how long does the journey take. How long do people want on the ice. [page 9]

Feelings: Confidence to undertake the various jobs; Honesty (when dealing with money). Motivation to carry out the job. Persistence to see the job through. Respect for others.

Skills: Being able to: calculate costs; use a telephone write a letter; collect names; make decisions; communicate ‘personally’.

Figure 2. A framework for knowledge. feelings and skills

Broken down in this way it is easy to see how young people can flounder when they are told by workers to go away and organise something themselves. A more truly educative approach would involve: [page 10]

- Assessment: where people are helped to recognise their strengths and weaknesses in relation to organising the trip. This might, for instance, take the form of the worker asking individuals what they feel their strengths and weaknesses are, or a group of young people working it out for themselves. (In the example this process happened informally – Mike, who was a milkman and therefore used to dealing with figures, handled the financial side of the trip. The educational problem here is that someone’s ‘strength’ was being reinforced rather than a ‘weakness’ counteracted.) It should also be remembered that assessment is not a ‘once and for all’ event but a continuing process happening in all the stages and modifying people’s actions.

- Setting objectives: where the people involved set specific targets for themselves. Frequently objectives emerge fairly easily and obviously during assessment but when they don’t, people may need some help in getting their objectives into a form that leads them into action. An example of objective setting is Tony’s assessment that he was very unconfident about using the phone to book the coach – it was something he hadn’t done before — and his volunteering to do that job.

- Learning/doing: where the necessary knowledge/feelings/skills are gained. To carry on with the example of Tony – he teamed up with Sue who had done much of the organisation of the previous trips and was able to explain to him exactly what he needed to do and say. He then felt able to make the call. (We can see things didn’t go smoothly—in his first call to the coach firm he forgot to ask the cost!)

- Evaluation: where people reflect on what has happened and check whether their objectives have been met. In more formal groups this could be an item on the agenda. In the sort of situation described here it could simply involve the worker or another member of the group checking with an individual or the group whether they felt things had gone as they wished. (This four stage approach is similar to that suggested in Social Skills & Personal Problem Solving. A handbook of methods. See Further reading.)

Written like this the headings give the impression of airtight compartments when in reality it is a process whose parts greatly overlap. For instance learning takes place in all four ‘stages’ — often the realisation by an individual (during “assessment”) that s/he has a particular strength or weakness is a significant piece of learning. It also appears a far more formal process than it is. All it really does is to put [page 11]things into a framework that workers (and young people) can internalize so that they have an almost automatic way of analysing things. Organising a skating trip is a fairly major exercise but the everyday tasks around the club, like running the canteen, give workers the chance to use the framework to help people develop abilities without making a big production number of it. A simple example is when a member asks to go on the door. The two-minute conversation that follows would benefit from having the knowledge/feelings/skills framework as the basis for making the decision.

The major outcome of such developmental ways of working is not necessarily people’s ability to organise a trip or take money on the door but their all round ability to solve problems. ‘Knowledge/feelings/skills’ and the four stages involved in ‘problem solving’ are ways of looking at things that young people can latch onto quickly. They can be applied to many of the decisions and situations people have to handle. For this reason it is important that the framework is made an explicit part of the work.

Lastly it needs to be remembered that workers are also part of the process — they themselves have strengths and weaknesses that need to be understood and acted upon.

In conclusion

From what has been said so far we can say:-

- Social education is about process rather than product (creation not consumption).

- A comprehensive approach to education involves the conscious development of certain knowledge, feelings and skills.

We will go on to look in more detail at how this works in practice and what an appropriate definition of social education might be.

Mark Smith (1982) Creators not Consumers. Rediscovering social education 2e, Leicester: National Association of Youth Clubs.

Reprinted with the permission of Youth Clubs UK.

Chapter 1: pages 5 – 11.

© Mark Smith 1980, 1982

© Mark K. Smith 1980, 1982