Chapter 2 of Mark Smith’s exploration of youth work and social education – Creators not Consumers. Rediscovering social education (1982).

contents: · breaking down events · opportunism · learning by experience · being participative · the social context · conclusion ·

[page 12] The skating trip gives us a flavour of what social education might mean in practice. In the next few pages I want to look more closely at five elements of the way the skating workers appeared to operate. They:

- tried to break down complex events into usable pieces;

- used existing opportunities rather than created them;

- used ‘learning by experience’;

- were participative; and

- put their work in its social context.

a. Breaking down events

When Neil suggested the skating trip, the workers asked him to take a board round to try and get a list of likely participants. It was other young people who undertook the more complex tasks. If the workers had asked Neil to do the phoning and calculating it is quite likely he would have refused. They were taking one step at a time.

When we looked at the knowledge, feelings and skills involved in the organisation of the trip, the complex nature of doing something fairly straightforward was revealed. It is easy to forget the worries and difficulties we ourselves experienced as youngsters when faced with similar tasks for the first time. Neil was able to handle getting names.

[page 13] There is a danger when starting small, of under estimating what young people can do. Subsequently Neil did take on more complex tasks— such as organising the lorry for the carnival float — but the process took some time and was deliberately unforced. With other individuals the pace is likely to be different and workers should be far more ready to take risks and force issues. Their ability to do this partly depends on how well they know the individuals concerned — risks need to be calculated. It also depends on the workers’ own feelings and skills. There is a need to take chances, to risk failure, not just for the young person’s development but also for the workers’ own well-being. Workers cannot afford to go stale.

The above applies to situations where the individuals concerned have some control, that is, where it is possible to start small. Many of the ‘crises’ young people experience are not spread over time and don’t start small. Events bunch and appear out of sequence but the same principle applies — that is to break issues down into what is usable, to explore the areas where the individual or group does have some understanding and control. A good example of this type of crisis is when young people have to appear in court for the first time. They need to be able to present themselves, understand the procedures and the consequences, handle their feelings and so on. A court appearance is usually seen as a very significant event by the young people concerned. It therefore provides unusually large possibilities for learning if handled properly. The difficulty as far as the worker is concerned is dealing with this sort of ‘crisis’ is often very time consuming and involves him/her in some difficult choices.

One, largely unintended, consequence of this way of working was that it was a group rather than an individual that organised the trip. So far the focus has been on the development of individual competencies. An approach which also emphasises the development of collective ways of working has significant implications for social education as we will see later.

b. Opportunism

By opportunism I mean that the workers tried to respond to life as it was being experienced rather than, say, laying out a programme which states ‘relationships’ will be done on such a date, ‘contraception’ on another. Such a clean developmental approach does not fit well with what actually happens in young people’s lives. As already mentioned things often happen all at once rather than being spaced over a period and the “easy crisis” need not appear first. Many workers have discovered that on the whole it is unnecessary to manufacture events or stimuli in order to set people thinking. In fact opportunities for learning exist in such profusion that workers are faced with a major problem of [page 14] choice. A key factor here is the workers’ ability to recognise and then use the material. This can be illustrated by the following comments from one of the “ice skating workers”: –

“I was sat in the office one Tuesday morning when John came in asking to use the phone to fix an appointment with the social security. He didn’t know the number so I gave him the phone book. After a couple of minutes he threw the book down, said he couldn’t be bothered and left. A week or so later on a club night he wanted to phone up one of the local pubs to finalise a darts team. This time he looked at the phone book, said he couldn’t see the number and gave it to me to look up. The number was there all right and I twigged that John couldn’t use a phone book”.

The worker went on to describe how he had waited for a private moment with John to broach the matter and how he had helped John to construct a small telephone book of his own useful numbers — alphabetically arranged. He still had problems with telephone books (especially the Yellow Pages) but a start had been made.

The fact that the workers were attempting to deal with situations that were felt to be significant by the young people themselves meant that there was the possibility of some ‘extraordinary’ learning (as in the case of court appearances), but this has to be set against the random and [page 15] patchy way in which it is taking place. The difficulty with opportunism is that there is a very real danger of throwing the baby out with the bath-water. There is a place in youth work for manufactured stimuli even if it is as simple as putting a newspaper out in the coffee bar or a poster on the wall. Exactly because events often bunch it is not possible to pull out of a particular piece of experience all the various strands at the time, so it will be necessary to try to encourage thought at other times.

Being opportunist is not an excuse for not thinking about or planning the work. For opportunism to be successful workers need to bring to each situation a way of judging what their response should be. ‘Knowledge, feelings and skills’ is one framework, their personal values and knowledge of the people involved are two others. All this amounts to a considerable “hidden curriculum”.

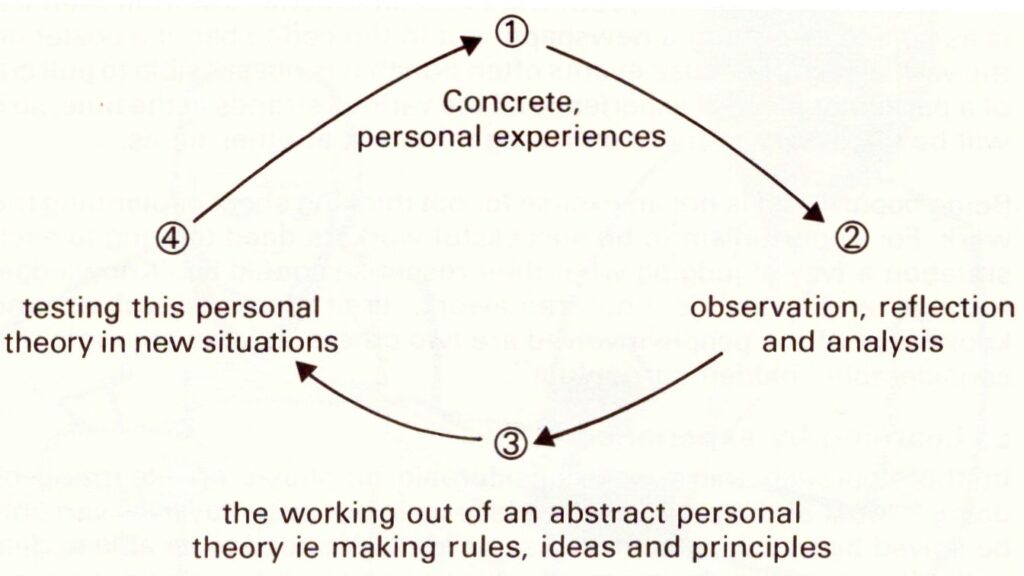

c. Learning by experience

In this approach there is a considerable emphasis on “learning by doing”. Most of the problems that face us in our everyday lives can only be solved by us taking action of some kind. We need to be able to deal with officials, make decisions about money, search for information and so on. Yet little has been done in the past in formal education to help people gain the knowledge, feelings and skills necessary to perform these tasks.

Learning by doing (experiential learning) is based on three assumptions, that:

- people learn best when they are personally involved in the learning experience;

- knowledge has to be discovered by the individual if it is to have any significant meaning to them or make a difference in their behaviour; and

- a person’s commitment to learning is highest when they are free to set their own learning objectives and are able to actively pursue them within a given framework

In recent years there has been a growth in teaching social skills, but teachers have faced considerable difficulties because they are dealing with experience at second or third hand. In many respects youth workers [page 16] have the same difficulty. The workers involved with the ice skating trip were able to use a real event with an outcome (the trip) that definitely mattered not just to the organisers but also to the other twenty or so youngsters who wanted to go skating. The fact that people were engaged in something ‘real’, rather than say a classroom simulation, is a considerable aid to learning. Here the workers were able to see at first hand what was happening but for much of the time we have to deal with feelings and descriptions of events that we have little immediate or direct knowledge of. Workers are not there when Debbie gets hit by her father or when Stephen is rejected by his mates. Their knowledge is gained vicariously. Social educators therefore have to be sceptical about what is presented as “experience”. In a sense their most useful role is to help people identify and understand significant experiences. Yet this is not enough because one of the stranger aspects of adolescence is the way we try to cut ourselves off from certain new experiences.

Figure 3: Stages in experiential learning

[Based on Johnson and Johnson page 7 – see further reading]

In adolescence the individual is consciously trying to make sense of the relationship of the external world to him/herself. In doing so s/he is creating a sense of self, of individuality. At this time we are reaching a stage of sexual, intellectual and physical ‘readiness’, yet we have very little experience of these things to handle this growth. As Richard Sennett (1973) has said: [page 17]

“This is the paradox of adolescence and its terrible unease. So much is possible, yet nothing is happening; lifelong decisions must be made, yet there is little to conceive of it, life in which he is independent, for him to draw on in making up his mind.” (The Uses of Disorder, Harmondsworth: Penguin, p. 27)

At this moment in their lives young people are experiencing a new and disorderly world. They need to be clear on their relationship to that world so that they might create their own identity. To avoid being painfully overwhelmed there is a tendency to ‘invent’ or exclude experience to fit their own understanding. This process of assuming the lessons of experience without undergoing the actual experience itself can lead people into holding cruelly stereotyped views and teaches them how to insulate themselves in advance from experiences that seem likely to upset their identity. In other words there is a real danger of people gaining a fixed identity, of them becoming locked in a sort of perpetual adolescence. Workers therefore have to walk on something of a knife edge. On the one hand it is important that young people are not overwhelmed by new and painful experiences, yet on the other if people are to grow and develop they need to actually undergo new experiences. Youth work should not therefore see ‘learning by experience’ simply as a means, it is also an end— “learning to experience”. This is a point we will return to in our later discussion of developmental needs.

d. Being participative

“Participation” has a long and untidy history within youth work. It is an idea much talked about and much misunderstood. The most useful way of approaching the concept is to look at the four main working styles youth workers can adopt.

Telling – which consists if giving straightforward orders often without explanation.

Selling – where the worker has something in mind that s/he wants people to do, such as pony trekking, and then tries to persuade people that it is a good idea and that they should take part.

Participating – is when workers and members jointly make decisions. Thus both parties have some control over the final product.

Spectating – in this instance the workers don’t intervene in any way —they have no power over what the outcome might be. The members simply get on and do things themselves. [page 18]

Figure 4: Youth work styles

Telling ——– Selling ——– Participating ——- Spectating

Without a doubt ‘selling’ is the most common approach in youth work. Just as advertisers and marketing people have become more subtle in their selling over the years — so have youth workers. Instead of simply putting a notice up advertising a football team we might now engage in market research — surveying opinions and then promoting the most popular product. Selling in this form can often pass as participation but the significant difference lies in the fact that ultimately it is the workers who have the power — it is they who in the end define the product – the club’s “programme”. The only power the members have in this example is to ‘vote with their feet’ — they can take it or leave it.

Obviously each of these approaches shades into another and it is often difficult to place a particular piece of work precisely. However the framework can show a general direction. Within a club different pieces of the work can fall within different approaches. For instance members usually have little say in who the leaders are — they are told or sold a particular group of people. On the other hand they might have a considerable role in the making of the club’s programme. It is therefore important to clearly define the areas under discussion.

Here “participation” is being presented as one of a number of different means a worker uses in his/her work. A common mistake made in youth work is to see participation as an end in itself. In some reports and pieces of writing the word seems to have gained an almost magical status. The significance of “participation” is in how it can help social education. For instance we have already discussed the need for young people to have certain new experiences so as to develop. One thing a participative style [page 19] does is to value their contributions and thoughts and this is a new experience for many young people.

Three major and inter-related sets of reasons are given by workers as to why a participative way of working is appropriate to youth work:-

- It matches their personal values and attitudes. In general participation reflects an optimistic view of the world, whilst a reliance on strict hierarchical structures tends to show a pessimistic view of human nature. One of youth work’s main values (as we will see later) is the belief that there is good in everyone.

- It makes sound management sense. Youth groups, because they are heavily dependent on the voluntary effort of both adults and young people, should have a method of management that recognises the special status and needs involved. When people feel, and are, involved in the making of decisions they are more likely to carry the decisions out.

- It makes good educational sense. For reasons already discussed, a participative style allows increased motivation and communication and the learning involved in working in groups.

There would seem to be seven main requirements for a participative style of youth work.

- Decisions should be taken by the appropriate people. This is made possible by having clear decision making structures that follow the principle of taking decisions where they hurt. That is to say the decision is taken by the people it will affect most. These structures should be adhered to.

- Decisions should be taken in groups. Participation is a communal experience, it is not simply making sure that everyone is consulted. Participation is about encouraging people to act and think collectively, to co-operate, and to feel part of a group. This is not to say that every single decision needs to be taken in a group but that decisions need to be taken with reference to a group. All this has implications for the size of groups. Whether the club has 30 or 1 50 members, on the whole they will have roughly the same number of committed and active members who share in the organisation and running of the group. Splitting the group and improving staffing ratios are only limited solutions. A participative style, if it is to be successful, therefore, involves the use of reasonably small units.

- The decision must be real. The issues should be significant and the decision acted upon. One of the most common criticisms made of ‘participation’ in youth work is that the matters covered are trivial and that outcomes are conveniently forgotten if they are not to the worker’s taste. [page 20]

- Decision makers should be accountable for their actions. Two points need noting here. First, people should not on the whole be shielded from the consequences of their decisions. Where unpleasantness or difficulties result from a decision made by a group of young people, it is not uncommon for workers to step in to ‘protect the youngsters’. This rather cuts across the educational nature of the experience. People have to learn that participation also involves taking responsibility for your actions. Second, where participation involves the use of small groups, it is crucial that some mechanism is adopted that keeps the group or committee in close touch with what the wider membership thinks. Furthermore, such groups should be accountable to the wider membership for their actions.

- The decision makers must have the knowledge, feelings and skills necessary. Thus they must have adequate information, the ability to work together as a group, confidence and so on.

- A youth work style should be adopted that enables people to have the appropriate opportunities, resources and abilities. So far there have been a number of things suggested for this — a concern for process, starting small and using learning by doing. Further suggestions are made about workers’ values and attitudes and the need to put the work in its social and political context.

- Participation needs time. It takes time for people to develop skills (and to realise that they have developed them!). Time is important on two counts. First it is usually necessary for a group to exist over a period of time for the necessary feelings and attitudes to grow. Second workers need to devote substantial time to such projects.

The ice skating workers were fairly strong on the last six requirements but weak on the first. The structures in which the young people were operating were not that clear or appropriate. The club did have a members’ committee which included several of the people involved in organising the trip to the ice rink in London. Yet the decision to organise the trip was taken on the spur of the moment by the workers and members that happened to troup into the office with Neil that club night. There was no question that the committee would have approved the trip especially as several of its leading lights were involved but that sort of instantaneous by-passing is bound to undermine it. Herein lies a tension which has to be resolved – between the desire of the workers to be able to respond quickly and the need for consistency and fairly rational decision making. Another course in this instance might have been to encourage Neil to get a list of names and to present a case at the next members’ committee. [page 21]

In this particular example the workers were also not as strong as they might have been on the second requirement — that decisions should be made in groups. As we have seen the decision to go ice skating just happened — it involved a number of people — but were they a group? The first decision, to gauge the members’ response, was taken by the workers and Neil. The second, to book dates, the rink and the coach, was taken by a number of members including some of the members committee. The next decision about cost and financial arrangements was taken by three members of the committee — Mike, Sue and Tony. Such a mish mash worked and was acceptable because there was a history of participation in the club and because the process was progressive i.e. in the end it was the people who had responsibility for finance who actually took decisions about money and costs. The people involved did feel a part of a group— they were all fairly central members of the club. However, had there been any problems or disagreements at this stage then the fragile nature of this sort of ad-hoc approach would have been shown.

There is a real danger in this sort of situation of the worker getting drawn into taking on what seem attractive roles for him/herself and so denying young people access to learning. One of the most difficult times for workers using this approach is when things appear to be going wrong. Does the worker stride in and save the day or does s/he remain in an enabling role even if it means the thing the members are organising fails? In some cases the experience of failure may do more harm than good, in others it can be a valuable experience. The only general rules here is that the young people concerned must agree to the worker taking on a different role (like selling or telling) and that any action taken must help meet peoples’ developmental needs.

e. The social context

One of the topics the workers often talked over was the extent to which their work was about containing ideas and behaviour that the rest of society found undesireable. These conversations were often sparked off by remarks about the character of the club’s membership. A good number of the members were in some sort of trouble with the law or were what the social workers called “at risk”. The youth office had an ambivalent view of these young people. On the one hand they frequently justified their share of the resource cake by claiming that money spent on the youth service stopped vandalism and anti-social behaviour but on the other they complained about the bad name such young people gave the club. The idea that youth work was simply about curbing vandalism and so called anti-social behaviour disturbed the workers. There was no doubt that the workers wanted to encourage changes in young people’s attitudes and behaviour. They were concerned about the unhappiness [page 22] and pain that ‘trouble’ both reflected and caused but they tried to link the troubles with broader issues.

Making links is important. Many personal troubles simply cannot be dealt with by the individual or their immediate family or friends because they are linked with public issues. (C Wright Mills talks about this relationship in The Sociological Imagination, Penguin, 1970, p 14—16). An illustration of the relationship between personal troubles and public issues is the housing situation currently facing young people. A young woman or man who wants, but cannot find, suitable accommodation has a personal trouble. On the other hand the lack of adequate housing is a public issue. When a worker helps to find someone accommodation s/he is tackling a personal trouble only. Currently there is less adequate accommodation for single people than people wanting it, thus only a limited number of personal troubles can be solved. Consequently workers, if they want to help in alleviating all personal housing problems they must also work with young people on the public issue — the expansion of local housing for single people. By setting the personal in its social and political context and, for instance, recognising that housing is a political problem, these workers were taking an important step. They were no longer suggesting that it was the young persons ‘fault’ that they could not get accommodation.

The nineteenth century philosophical origins of youth work have, over the years, given strength to the view that individuals are to blame for their misfortunes. It was people’s own fault, for instance, that they were poor or ill. What was wrong was people’s inability to save, rather than the economic system which gave them low wages. Youth workers therefore needed to instill the relevant virtues such as thrift and self discipline in their young charges. By being careful and working hard poverty could be avoided. This lack of sociological understanding was mirrored in the sixties and early seventies where youth workers adopted the group work methods of writers like Carl Rogers. Here again was the concentration on the individual and his/her immediate group which led to an overemphasis on psychological factors and an ignoring of the social context of the work. Such analysis, whilst perhaps helping people in one direction, may have disabled them in others.

The skating workers were keen to make connections, to understand private troubles within their economic/political setting. One of the main links they made in this respect was with class. Most of the club’s members came from two adjacent council estates and their values, attitudes and way of life could only be described as working class. One of the most common feelings amongst young working class men and [page 23] women is their sense of powerlessness in the face of the major economic and political processes that govern their lives. To be told that it is their ‘fault’ that they are unemployed or can’t get housing, for instance, is to further compound that sense of resignation and powerlessness. This is the importance of making connections — not only does a better understanding lead to the possibility of more realistic action — but it liberates people from the burden of unnecessary guilt. It suggests that the most useful role a worker can adopt is to separate the “problem” from the person. Because a problem affects a particular individual or group it does not mean it is of their making. And because a problem is not wholly of their making it can only be solved when consideration is given to all the major factors involved. This is the challenge facing youth workers — to recognise that many personal troubles cannot be solved merely as troubles, but can only be fully understood in terms of public issues.

In conclusion

In this chapter I have looked more closely at five elements of the way the ice skating workers operated. They:

- tried to break down complex events into usable pieces;

- used existing opportunities rather than created them;

- used “learning by experience”;

- were participative; and

- put their work in its social context.

This group of workers were only able to work in this way because they had a shared and common set of aims and objectives and they knew what each other were doing. In other words, they were a team. For these workers at this stage, the sense of common purpose had come about more by luck than judgement. They were friends, had similar backgrounds and interests, and met socially. They often talked about the club and its members. However, they were very unsystematic in the way they did these things and a few months after the trip, when some pretty basic decisions had to be made about the future of the club, the need for a more formal and systematic approach to the staff team became apparent. For this sort of approach to be successfully applied we must therefore add a sixth element — the need to create and maintain a team approach to youth work.

Mark Smith (1982) Creators not Consumers. Rediscovering social education 2e, Leicester: National Association of Youth Clubs.

Chapter 2: pages 12 – 23

Reprinted with the permission of Youth Clubs UK..

© Mark Smith 1980, 1982