The first settlement to be established outside London, and an extension of its parent institution at Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel, Manchester University Settlement was nevertheless, explains Stuart Eagles, deeply rooted in the specific political and cultural history of Ancoats. It, and Manchester Art Museum, owed much to the work of Thomas Coglan Horsfall.

contents: introduction · ruskinian origins of ancoats art museum · the establishment of the art museum in ancoats · a new university settlement · marriage · decline and separation · references · about the writer · acknowledgements · how to cite this piece

______

Manchester University Settlement was the first settlement to be established in Britain outside London (in 1895). It was:

Founded in the hope that it may become common ground on which men and women of various classes may meet in goodwill, sympathy and friendship, that the residents may learn something of the conditions of an industrial neighbourhood and share its interests, and endeavour to live among their neighbours a simple and religious life. (Rose and Woods 1995: 13)

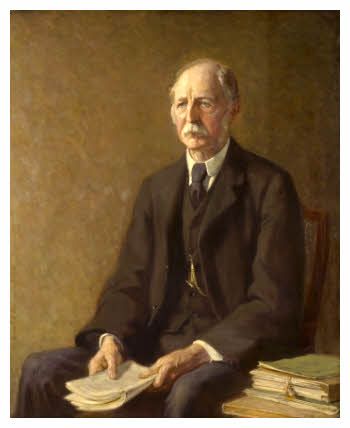

In this piece, we explore its development, and that of the Manchester Art Museum, as well as comment on the pivotal contribution of Thomas Coglan Horsfall (1841-1932).

The Ruskinian origins of the Art Museum in Ancoats

The most significant of these was his Art Museum, established as a direct response to the art and social critic, John Ruskin (1819-1900). In 1918, Thomas Horsfall explained in a letter to a Manchester Councillor that the museum had been specifically ‘formed for the purpose of giving effect to Ruskin’s teaching’ (quoted Harrison 1985: 121). To love beauty was to reaffirm a true Christian faith, and Horsfall’s commitment to a belief in the personal and wider social benefits of appreciating beauty through art also reflected his sense of personal indebtedness to Ruskin. It was from Ruskin that he derived his strong commitment to civic duty, and it was no accident that when he wrote, ‘men in my position have almost the same duties as officers have towards the soldiers they lead’ that it echoed Ruskin’s appeal in his seminal work on political economy, Unto This Last (1860, 1862), to the ‘captains’ of industry to lead by example (quoted Harrison 1985: 121). Art, extended to the poorest members of the community, became a social mission. ‘Art owes its high value to us’, Horsfall wrote, ‘to its relation both to the beauty of the earth and to human feeling and thought’ (Horsfall 1910: 14).

Thomas Horsfall and John Ruskin corresponded extensively and publicly, and Ruskin gave Horsfall’s project his approval, despite a lifetime’s hostility to Manchester, the city which had come to symbolise everything that Ruskin deplored. His hostility arose, not merely with regard to modern industrial society, but specifically about the economic system of laissez-faire, the so-called ‘Manchester School’ of economics, which underpinned it. When Ruskin referred to Manchester as ‘the greatest Mercantile City in England’ he implied no compliment (Ruskin 1903-1912: 29.519). ‘I perceive that Manchester can produce no good art and no good literature,’ he wrote in Fors Clavigera (1871-1884), his monthly letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain, adding for good measure, though not as any kind of personal insult to Horsfall himself, that ‘it is falling off even in the quality of its cotton’ (Ruskin 1903-12: 29.224).

In his introduction to Thomas Horsfall’s The Study of Beauty (1883), Ruskin implored him to spend his ‘artistic benevolence on less recusant ground’ (Ruskin 1903-12: 34.429). Ruskin had counselled that ‘until smoke, filth, and overwork are put an end to, all other measures are merely palliative,’ yet despite such caveats, the general tone of Ruskin’s letters to Horsfall reveal that beneath the hostility was a supporting faith in the justice of attempting such a project (Ruskin 1903-12: 37.624). ‘The future of England may be, for aught I know, redeemable,’ Ruskin admitted, nevertheless insisting, ‘but she must first recognize her state as needing redemption’ (Ruskin 1903-12: 29.592).

Horsfall passionately believed in the redemptive power of art, and as with the ideal St. George’s Museum, the small space Ruskin had set aside for the edification of working men in Walkley, Sheffield, as part of his utopianist Guild of St. George, Horsfall’s Art Museum would be small, selective, educational, and specifically targeted at the working man, although Horsfall also felt that the greatest potential art possessed for engendering social progress and spiritual enlightenment rested with the young. Parties of local children, including school-based groups from every district in Manchester, were welcomed to the Art Museum, and a sense of missionary zeal lay behind the concept of a schools’ picture loans collection. In 1890, 45 sets of 12 pictures were circulated in loan exhibitions to schools, mainly funded with £1000 from Horsfall himself, in a project which resembled the work of the Art for Schools Association, founded in 1883, of which Ruskin was President. Horsfall obtained an amendment to the Education Code, after a meeting in 1894, which permitted schoolchildren for the first time to visit museums, art galleries, historic buildings and botanical gardens in school hours as part of their education.

Thomas Horsfall believed sincerely that the Christian Church could help effect progressive social reforms. In promoting the Manchester branch of the Church Reform Union, which was based around a belief in the power of action and the unity of Christians in serving God’s will whilst simultaneously disparaging dogmatic debate, Horsfall said: ‘we find that what we have habitually done has had far more power to determine what we believe than the beliefs with which we started life have had to determine our actions’ (Manchester City News, 4 December 1880). For Horsfall, social engagement was not merely an expression of his Christian faith, it helped to sustain it.

The establishment of the Art Museum in Ancoats

The Art Museum Committee was formed in December 1877, with the support and involvement of the Manchester Literary Club, the Manchester and Salford Sanitary Association, of which Thomas Horsfall had long been a member, the Manchester Statistical Society, local branches of the Sunday Society, the Ancoats Recreation Committee, and, from 1879, the Ruskin Society. Owens College and the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts were also involved, and support came from the Manchester Guardian in the shape of journalists W. T. Arnold and C. P. Scott.

Despite a general air of moral support, the local and national depression was partly responsible for a lack of funding for Horsfall’s Art Museum project, and the delays this caused were compounded by difficult negotiations with Manchester Corporation. Although rooms were initially taken for the Art Museum at a new gallery in Queen’s Park, in north Manchester, relations between the Art Museum Committee and the Parks Committee broke down, and the former seat of the Mosley family at Ancoats Hall on the western bank of the River Medlock was not eventually secured until 1886 when it became the Museum’s home. Ancoats, in Manchester’s East End, consisted of cramped back-to-back jerry-built housing, with a densely-packed, largely immigrant population all competing for a gasp of the industrially-polluted air that swirled around the cotton mills, iron foundries, coal wharves and slaughterhouses, squeezing through the tight alleyways and narrow canals. Like Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel, the Art Museum at Ancoats stood as a cultural beacon on the edge of the dirtiest, dreariest neighbourhood.

The socialist, Charles Rowley (1839-1933), had earlier worked in Ancoats, both through the Ancoats Recreation Scheme and from 1889 the Ancoats Brotherhood, advocating a cleaner physical environment and greater access for all to things of beauty in an attempt to ameliorate the suffering of the poor. Extension lectures at Ancoats in the 1880s attracted much attention, with 500-900 men attending on Sunday afternoons to hear some of the country’s leading speakers. Rowley’s group also co-ordinated concerts and excursions. The wealthy engineer, Francis Crossley, had also established a missionary hall nearby.

When the Art Museum opened, its rooms, variously dedicated to painting, sculpture, architecture and domestic arts, together attempted to provide a chronological narrative of art, with detailed notes, labels and accompanying pamphlets and, not infrequently, personal guidance, all underlining a sense of historical development. John Ruskin himself provided some copies of Turner, and a copy of Holman Hunt’s The Triumph of the Innocents (1876-1887), framed by C. R. Ashbee’s Toynbee Hall-based Guild of Handicraft, once hung in the gallery. Alan Crawford has written:

It is hard to imagine an object more strongly associated with the vanished late Victorian ideal of social reform through art than this, with its reproduction from Holman Hunt, its quotation from Ruskin, made in London’s East End by reformed craftsmen to bring light and culture to the poor of Manchester. (Crawford 1981: not paginated)

It is a symbolic representation of Horsfall’s Ruskinian mission, linking art, Ruskin, social reform and the university settlements.

The Museum was essentially a Ruskinian experiment, with many of its most ardent supporters sharing Thomas Horsfall’s enthusiasm both for John Ruskin and for civic engagement. These included the prodigious local author, journalist and deputy chief librarian, W. E. A. Axon (1846-1913), the solicitor, Methodist, journalist, local councillor, and extension lecturer, John Ernest Phythian (1858-1935) and the later Principal of Dalton College, Manchester, John W. Graham (1859-1932), the Quaker.

The Museum boasted a Model Workmen’s Room and Model Dwellings’ Sitting Room, which spawned craft classes in woodwork and drawing, and paintings of nearby beauty spots breathed an albeit short life into an associated rambling club. Free music, lectures and entertainments on weekday evenings and Sunday afternoons proved popular, as did children’s concerts and readings. From 1892, a new concert hall was built to hold 600 people, and visitors to Ancoats Hall steadily increased throughout its first decade. This varied activity, reaching far beyond the bounds of any art gallery which predated it, including Ruskin’s Museum in Sheffield, underscores its ambitious missionary intent. The first Annual Report makes the matter clear: ‘the mere exhibition of works of art, even with the aid of written and oral explanation, would not suffice to attract a sufficient number of visitors to the Museum to make it a force in the neighbourhood’ (First Annual Report of the Manchester Art Museum 1886: 1). The local philanthropist, Oliver Heywood (1825-1892), had significantly claimed the same year that the Art Museum was a ‘Toynbee Hall’ for Manchester.

A new university settlement

Thomas Horsfall shared the belief of the pioneer of university settlements, Canon Samuel Barnett, in a practicable ‘socialism’: civic engagement at a grass-roots level, with cross-class co-operation at the base of a mutual exchange of social experience and informal education. The eventual marriage between the Ancoats Art Museum and a new university settlement was inevitable.

Horsfall had been present, and had spoken, in May 1883, when Barnett had addressed the students of Oxford University’s Palmerston Club on ‘Our Great Towns and Social Reform.’ From its inception, Toynbee Hall had itself enjoyed Horsfall’s generous financial support. He believed, as Barnett did, that ‘It is impossible to make the poor rich, but it is possible by ‘nationalising luxury’ to make more common the better part of wealth’ (quoted Harrison 1985: 126). He did not mean state nationalisation, but greater access for all to ‘wealth’ as Ruskin defined it, to life-enhancing cultural experiences such as that offered by the best art.

As early as 1884, Horsfall had written, ‘Once let the lowest classes cease to receive the large number of recruits from the higher grades of the working class who fall into vice, crime, pauperism, chiefly through the dullness and miserableness of the life of our towns, and the community would be able to break up its criminal and pauper class’ (Horsfall 1884: 29). Horsfall’s belief was the art could transcend social barriers, and prove transformative for those touched by it. In 1895, he remembered the middle decades of the century when ‘the existing disastrous division of classes was in a less advanced state’ (Horsfall 1895-6: 14).

Thomas Horsfall’s Art Museum had already reached out to the people, and it was natural that a new university settlement should ally itself to his foundational work. The settlement’s first historian, Mary D. Stocks, wrote that the Art Committee ‘had become under Horsfall’s leadership an active body for the encouragement of public interest in art and nature’: ‘What Miss Miranda Hill and the Kyrle Society were doing in London (see Octavia Hill), the ardent volunteers of the Art Museum were doing in Manchester; all that and more’ (Stocks 1953: 13).

The university settlement grew out of a meeting at Owens College. Barnett addressed their Union on 27 March 1895, where those present recognised ‘the desirability of setting on foot an organization of social work in Manchester, in the spirit of the University Settlements Scheme as explained by Canon Barnett and the Right Hon. Sir John Gorst’ (Stocks 1956: 6). The founding committee appropriately appointed Horsfall as chairman. With the Art Museum now informally sharing a base around Ancoats Hall with the Manchester University Settlement, the two institutions worked closely together, the museum borrowing the settlement’s residents for lectures, and in turn providing the lecturers with a collection of practical teaching aids and illustrative materials. University men and women now lived among the poorest residents of Manchester, each and all learning from their mutual exchange.

Marriage

The two institutions, the Art Museum and the University Settlement, were formally amalgamated in 1901. Stocks wrote, ‘For six years they had striven for the same ideals, occupied the same premises, engaged the energies of the same workers, provided members for one another’s committees, breathed the same smoky air, appealed to the same obtuse public’ (Stocks 1956: 17).

From the following year, with the arrival of the energetic T. R. Marr from the sociologist Patrick Geddes’s pioneering civic experiment, the Outlook Tower in Edinburgh, the scope and breadth of activities engaged in by the joint organisation was expanded, as demonstrated by the establishment of Marr’s and Horsfall’s Citizens’ Association for the Improvement of the Unwholesome Dwellings and Surroundings of the People, in 1902, which was the principal stimulus in Manchester for housing reform. It encouraged favourable opinions of developments such as those at Burnage Garden Village, Chorltonville and Blackley. It marked the beginning of a productive decade, what the settlement’s historian called ‘a kind of golden age’ (Stocks 1956: 22).

In 1904, Horsfall wrote of the ‘masses of undersized, ill-developed and sickly-looking people … to be found in the poorer districts of London, Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, and all other large British towns’ (Horsfall 1904: 161). He saw housing reform as essential for public health. J. J. Mallon (1874-1961), the jeweller’s assistant recruited to the Manchester settlement from the trade union movement, later wrote:

Roused by Horsfall and Marr, those at Ancoats campaigned against bad housing. Under a one-party banner we went into local politics and in a conflict which seemed to us to make history carried T. R. Marr, our housing candidate, to the City Council. We formulated a municipal programme and explained it at local street corners. We demonstrated – we were always demonstrating. (Stocks 1956: viii)

The Annual Report for 1904 underlines the point:

It is not enough that in our rooms tired people may find pictures and other beautiful objects among which they may forget their weariness – or that from time to time Concerts, At Homes, and other gatherings bring the refreshment of music and good company to our neighbours… Alongside these other activities, therefore, we must develop and stimulate a healthy and vigorous sense of citizenship, which in time will find its expression in the work of our municipality. (Manchester Art Museum and University Settlement Annual Report 1904: 10.)

Yet, like the earlier Art Museum, the settlement was ‘at the outset, primarily an educational settlement’ (Stocks 1956: 18). Early lecturers included A. J. Carlyle (1861-1943) on Thomas Carlyle and Ruskin, J. J. Mallon and L. T. Hobhouse (1864-1929) teaching politics, and the socialist J. R. Clynes (1869-1949) lecturing on trade unionism. The old Art Museum entertainments and civic engagements were extended and augmented.

[There were] readings to the blind, penny banks, social evenings, dances, poor man’s lawyers, clubs for boys, clubs for girls, clubs for the casual denizens of common lodging houses, clubs for cripples; and always, everywhere, individual personal attention such as neighbours give to neighbours for the remedy of their unclassifiable misfortunes (Stocks 1956: 21).

The first building the university settlement added to the joint organisation was 20 Every Street, which for a short time at the end of the late 1890s had served as a residential working-men’s college, named Ruskin Hall, and affiliated to Ruskin Hall, Oxford. It became the base for the men’s settlement, and the women remained at Ancoats Hall.

In Manchester, as in London, university men and women were engaged directly with the educational needs and social conditions of the poorest members of the community.

Decline and separation

In February 1909, the former secretary of Toynbee Hall, the leading Ruskinian, John Howard Whitehouse (1873-1955) briefly became Warden of the settlement, but he would be the first of many who would not remain there for long. Both joint wardens of the women’s and men’s settlements, Alice Crompton and T. R. Marr, and another promising settler, J. J. Mallon, had all recently left the organisation, Mallon having been called away in 1908 as secretary to the Anti-Sweating League, campaigning on behalf of the Trade Boards Act. Although the settlement and Art Museum continued to do excellent work reaching out to the local poor, with such dedicated figures as settlement resident and Museum curator, Bertha Hindshaw, working particularly hard from 1912 to extend the joys of art to children, the institution steadily declined in significance.

By the end of the First World War, and after a period of slower activity, the social and cultural foci of the settlement and the art museum had become more distinct and their objectives diverged. The organisations were formally separated in 1918 – with the Art Museum being taken over by the City. It eventually closed in 1953 when most of the collection was transferred to the Manchester Art Gallery (formerly the Royal Manchester Institution). Graham, the long-serving honorary treasurer, resigned on falling ill in 1919, and the following year, Thomas Horsfall, by then elderly, disappointed by the depressing effects on business of the war, and grieving for a son killed in action, resigned his Presidency. Without its founding personalities to keep it together, and with the wider social changes which broadly saw the development of a state assumption of responsibility for social welfare and education, the art museum and the settlement shared little but their premises and neither would again reach the heights they had enjoyed in the late Victorian and Edwardian periods.

Further reading and references

Further reading

Kidd, Alan (2006) Manchester: A History, 4e. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing.

O’Gorman, Francis (1996) ‘Sage and City: John Ruskin and Manchester’ Manchester Memoirs: The Memoirs and Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, 135, pp. 55-70.

Rose, Michael (1989) ‘Settlement of university men in great towns: university settlements in Manchester and Liverpool’, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 139, pp. 143-4.

Skinner, D. F. (1947) ‘T. C. Horsfall: A Memoir’ mss. typescript [by Horsfall’s daughter] Manchester Local Studies Library, ref. Misc/690/11.

Works cited

First Annual Report of the Manchester Art Museum (Manchester, 1886).

Manchester Art Museum and University Settlement Annual Report (Manchester, 1904).

Crawford, Alan (1981) in C. R. Ashbee and the Guild of Handicraft, exhibition catalogue, Cheltenham: Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum.

Harrison, M. (1985) ‘Art and Philanthropy: T. C. Horsfall and the Manchester Art Museum’ in Kidd and Roberts (eds.), Manchester, pp. 120-147.

Horsfall, T. C. (1883) The Study of Beauty and Art in Large Towns, London.

Horsfall, T. C. (1884) Means Needed for Improving the Condition of the Lowest Classes in Towns, Manchester.

Horsfall, T. C. (1895-6) ‘The Government of Manchester’, Transactions of the Manchester Statistical Society.

Horsfall, T. C. (1904) The Improvement of the Dwellings and Surroundings of the People, Manchester.

Horsfall, T. C. (1910) The Need for Art in Manchester, Manchester.

Kidd, A. J. and Roberts K. W. (eds.) (1985) City, class and culture: Studies of social production and social policy in Victorian Manchester, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Rose, Michael E. and Woods, Anne (1995) Everything Went On at the Round House: A Hundred Years of the Manchester University Settlement, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Ruskin, John (1903-1912) The Works of John Ruskin Library Edition). 39 vols. Eds. E.T. Cook & Alexander Wedderburn, London: George Allen.

Stocks, Mary D. (1956) Fifty Years in Every Street: The Story of Manchester University Settlement, 2nd edn., Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Links

Manchester Art Gallery. The site includes a brief history of the Gallery and details of its collection including many of the pieces that came from the Art Museum in Ancoats.

Manchester University Settlement. This site outlines the current work of the settlement.

About the writer: Dr Stuart Eagles wrote an MA dissertation on Ruskin and Dickens at Lancaster University, and gained his D.Phil from the History Faculty at the University of Oxford, writing a thesis on Ruskin’s legacy for civic and national politics in Britain. He is the author of the forthcoming Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for Thomas Coglan Horsfall and has contributed to the Ruskin Review and Bulletin and to Carmen Casaliggi and Paul March-Russell’s (eds.), Ruskin in Perspective (Newcastle, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007).

Acknowledgements: The picture of Thomas Coglan Horsfall by Samuel Beaumont (1861-1954) is reproduced here with the permission of The Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester. All rights reserved. The picture of Ancoats Hall is reproduced with the permission of Chetham’s Library, Manchester. All rights reserved.

How to cite this piece; Eagles, Stuart (2009) ‘Thomas Coglan Horsfall, and Manchester Art Museum and University Settlement’, the encyclopaedia of informal education. [www.infed.org/settlements/manchester_art_museum_and_university_settlement.htm].

© Stuart Eagles 2009

updated: August 14, 2025