We have witnessed a long-running and comprehensive failure in housing policy across Britain. Scotland’s record is better than that seen south of the border – but is now in danger of failing badly. Mark K Smith explores what is going wrong – and what can be done so that all can have decent homes. This piece is also available as a pdf (A4) – click to download.

contents: introduction | the data | what is to be done | conclusion | references | acknowledgements

Housing is a fundamental human right. It is a gateway to other human rights, it offers safety and security giving individuals the opportunity to pursue other basic human rights like educational attainment, work and wellbeing.

All these rights are tied into having access to good quality, affordable housing. (Angela O’Hagan, Chair – Scottish Human Rights Commission 2024)

Introduction

Across Scotland, Shelter has reported, 1.5 million people are currently denied a safe, stable home. Many private renters face increasingly unaffordable rents and poor conditions, others have no permanent home. ‘The bottom line is’, Shelter argues, ‘the absence of good quality, affordable social housing is denying people across Scotland the chance of a decent home’ (Shelter 2024a). Housing is also fundamental to the eradication of child poverty. As Shelter and Aberlour Children’s Charity have stated:

… the importance of providing access to safe, secure and affordable homes cannot be overstated. Scotland is in a housing emergency with a failing homelessness system and falling numbers of social homes becoming available.

The result of this emergency is low-income families stuck in high-cost accommodation, unable to access social housing. We must build more social homes to reduce the numbers of families and children being pushed into poverty by high housing costs. (Shelter 2024b)

Over 24% of children in Scotland lived in relative poverty after housing costs in 2020-23 (Scottish Government 2024f). The Scottish Human Rights Commission has reported the apparent failure in Scotland to meet basic international obligations. These concern the right to food, the right to housing, the right to health, and the right to cultural life. They also report an apparent regression or deterioration of rights across the Highlands and Islands. ‘This is exacerbated by decisions on budget reductions or indeed the complete elimination of previously existing services, without sufficient mitigating measures’ (2024 p.8).

In May 2024 the Scottish Government declared a national housing emergency blaming UK government budget cuts and austerity measures. Sadly, the main roots of the problem go much further back. Governments have generally failed since the early 1980s to develop sensible and comprehensive housing policies. The decision by the UK Thatcher government to support the discounted sell-off of social housing was welcomed by many at the time. In retrospect, it was an error of grotesque proportions, especially when linked to economic and social policies that have led to growing income and wealth inequalities. As the cost of renting and buying houses has grown, younger people have become increasingly forced into privately rented accommodation. Thankfully, the Scottish Government called a halt to the sell-off in 2016. However, nearly half a million affordable rental homes had been lost in Scotland.

Here we will approach the housing crisis by exploring the situation in one Scottish local authority – Orkney. While some elements discussed relate particularly to rural and island settings, much of the analysis and argument applies across Scotland and the rest of Britain.

Three key factors have generated a heavy demand for homes in the County:

The islands attract a significant number of incomers (and some returners). A rich variety of work and study/research opportunities are on offer, and the County is known for the quality of life on offer.

People are living longer. Orkney has the highest average healthy life expectancy in the UK – 74.35 years (Renfree 2024), and the number of households with members over 65 is rising significantly.

There has been a hefty loss of housing to second homes – and short-term letting.

Other local authorities will have different profiles but experience similarly critical, outcomes. Central to these is a lack of social and affordable housing for younger people, families, and some groups of older people. The situation is further complicated by the large number of people living in houses far too big for them (and often with accessibility issues).

Local developers, and social housing providers such as the Orkney Islands Council (OIC) and Orkney Housing Association (OHAL), have not been able to keep up with these needs in recent years. Indeed, there has been a sizeable reduction in the supply of new social housing. Housing associations and councils across Britain have, of course, been limited by the failure of national governments in Britain to prioritise social and affordable housing developments and to fund them properly. Significant rises in building costs and interest rates have hit all sectors.

Our experience in Orkney will be familiar to many living in rural, coastal, and island communities. Politicians may talk about a housing emergency (or act as if it is an illusion), but key underlying issues are either ignored or glossed over. Here we highlight five fundamental areas for action – and explore the way forward. We focus, in particular, on the need to:

Prioritise – and focus on building – well-designed social, affordable, eco-aware rental housing.

Develop accessible and welcoming houses and localities that invite older people, in particular, to ‘rightsize’ and release larger properties for families and younger people.

Contain and reduce the number of second homes and holiday lets in order to increase the supply of housing available to local people and the amount of temporary/short-term accommodation needed for incoming workers, and for those who are homeless.

Actively support and finance community-led initiatives.

Encourage people to view houses as homes rather than investments and governments to significantly increase funding for new social and truly affordable rental properties.

In other words, we must unhook ourselves from the housing policies (or lack thereof) of the last forty or so years, and look, in particular, at the local development of social and affordable rental housing and living communities. All five areas apply, with particular force, to the situation in Orkney.

We will start with a collection of figures concerning Orkney’s (and Scotland’s) population and housing situation – and an apology. There is a lot to digest here.

The data

Here we highlight some of the main statistical elements that should be steering housing policy in the County – and explored across Scotland and the rest of the UK. The figures used are largely obtained from the 2022 Census (Scotland’s Census – Housing 2024) and other recent government sources. They provide a comprehensive statement of the situation faced. This differs in some ways from the 2023 Orkney Housing Need and Demand Assessment (OIC 2023) used in the Orkney Islands Council’s local housing strategy (2024b). We have used more recent data and tackled key omissions.

Population change

First, the population of Orkney is growing. In 2011 it was recorded as being 21,249, by 2022 it was 22,000 – an increase of 751 people or 3%. The size of the population may well be slightly different to this. Figures were adjusted because not everyone completed a census return. However, the return rate for Orkney was close to 94% and around 90% for Scotland. The population of Scotland grew by 141,200 or 2.7% over the same period. This was a significant drop from the 4.6% recorded in 2001-2011 (Scottish Census 2022).

Second, and significantly, the number of households in Orkney was up by 8.9% (9,725 in 2011 and 10,600 in 2022) – close to three times the growth in population numbers. This effectively required building, or bringing back into service, some 875 homes (i.e. 79 per year). In Scotland as a whole the total number of households increased by 5.8% since the 2011 Census (Scottish Census 2024). This was more than double the percentage growth in population numbers.

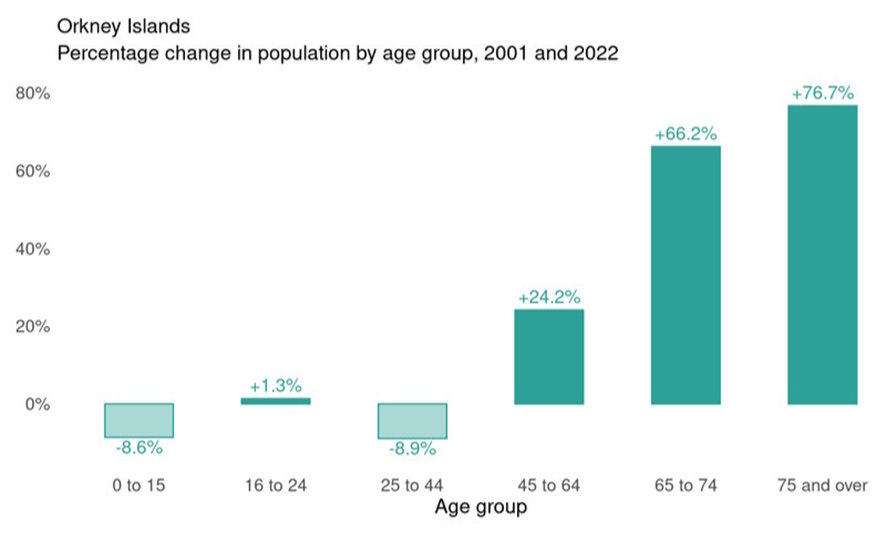

Third, the increase in the population and number of households in Orkney can be largely explained by the number of incomers and returners. There appears to have been a net migration in 2011-2021 into Orkney of 1662 individuals. This figure is almost completely made up of those aged 0-64 (close to 92%). The other main component of population growth is linked to people living longer – there were 1200 more over 65-year-olds in 2022 than in 2011 (Scottish Government 2024d) – some of which were incomers. By 2022, the age group constituted 24.9% of Orkney’s population – the sixth-highest percentage in Scotland (around 5,400 people). It was up from 19.8% (just over 4200 individuals) in 2011 (a rise of 5.1%). This compares with an average of 20.1% across Scotland in 2022 and 16.8% in 2011 (an increase of 3.3%). As also can be seen from the diagram below, between 2001 and 2022, there were decreases in the 0-15 and 25 to 44 age groups (-8.6 and 9%). The 75 and over age group saw the largest percentage increase (+76.7%).

(National Records of Scotland 2024c)

Fourth, as we will see, the ageing of Orkney’s and Scotland’s population has major implications for housing. Across Scotland, older people are far more likely to live alone than younger people. Around 1 in 6 people in households aged 16 to 54 lived alone in 2022 (14.1%). Around 1 in 3 people in households aged 55 and over, lived alone (30.1%). In Orkney in 2022, just over 8% of the total population (1844 people) lived alone and were over 65. A further 3487 people over 65 (or just under 16% of the population) lived in two or more people households. Another group of 97 people were listed as residing in medical or care establishments. By 2040 it is suggested that the 65+ population in Orkney will grow again by a third – around 2000 extra people (Shakespeare Martineau 2024, p.10).

Housing in Orkney and Scotland

Close to 70% of occupied properties are owned or part-owned. This compares with just over 63% in Scotland as a whole. This difference of 7% can be largely explained by the size of Orkney’s ageing population.

Across Scotland over 35% of households rented their homes. In Orkney, just under 17% of properties (1795) were social-rented and a little under 10% were privately rented. Just under 3.5% of properties were listed as having people living rent-free. Between 2011 and 2022 the number of households renting in the private sector decreased by around 7% while those in social housing increased by around 29% (or 250 households – close to 23 housing units per year) (Scotland’s Census 2011, 2024). These figures reflect a significant growth in the social housing provided by the Orkney Housing Association (OHAL) and the local council (OIC). This is particularly noteworthy, given that the ‘Right to Buy’ scheme was in place up until July 2016. Between 1979-80 and 2014-15 a total of 494,580 council and housing association homes had been sold at discounted prices in Scotland (BBC News 2016).

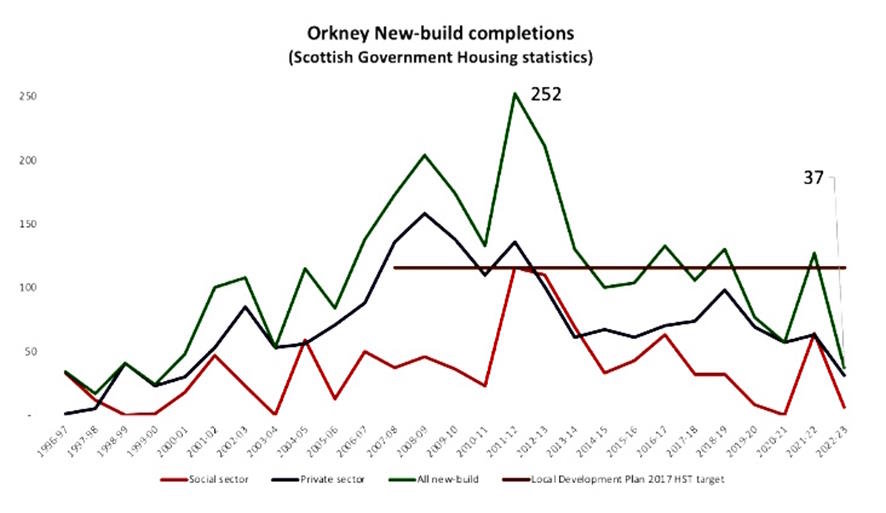

New starts: The situation has changed in Orkney in recent years. In the two years up to July 2024 only 31 new social housing starts were made (OIC – 14 and OHAL – 17) i.e. just over 15 starts per annum. This compares with a yearly average of 23 social housing starts for the previous 11 years. In the same period, there were 69 new starts for private buildings (just under 35 pa). (Scottish Government 2024c). The ten years before this period produced 1097 starts (just under 110 units per year) (op. cit.) – nearly three times the current annual figure. In addition, the new Orkney Housing Strategy (2024a) reports that the previous local housing strategy (2018/19-2022/23) had projected that 448 affordable homes would be built but delivered less than a quarter of this figure – 110 homes (under 28 homes per year). The dire nature of the situation is made clear in a graph in the strategy document (OIC 2024b p. 13):

Unfortunately, things had worsened in 2023-4. No local authority homes, and under 8 housing association units, were completed in Orkney (Scottish Government 2024c). The Strategic Housing Investment Plan (SHIP) (OIC 2021) had predicted 63 (although the figures appeared to add up to 59). The current SHIP is looking to build a total of 40 social housing units per year (split equally between OHAL and OIC) over the next 10 years (OIC 2024c). The new OIC strategy argues for 103 new builds per year (OIC 2024b p.13).

Given the scale of the current crisis, there could be significant problems around the supply of housing in Orkney. The SHIP does not look like an approach that will remove the current housing emergency. The strategy does, however, rightly recognize the need for a significant increase in social and mid-market rent properties. They would make up 56% of the proposed developments. Unfortunately, two essential questions are avoided:

- How this is going to be organized, financed and achieved; and

- Whether 103 builds is an adequate target – particularly given the impact of the housing crisis on young people and further increases in the number of older people.

At one level all this is not surprising given a similar lack of detail at a national level (both in Scotland and the UK generally).

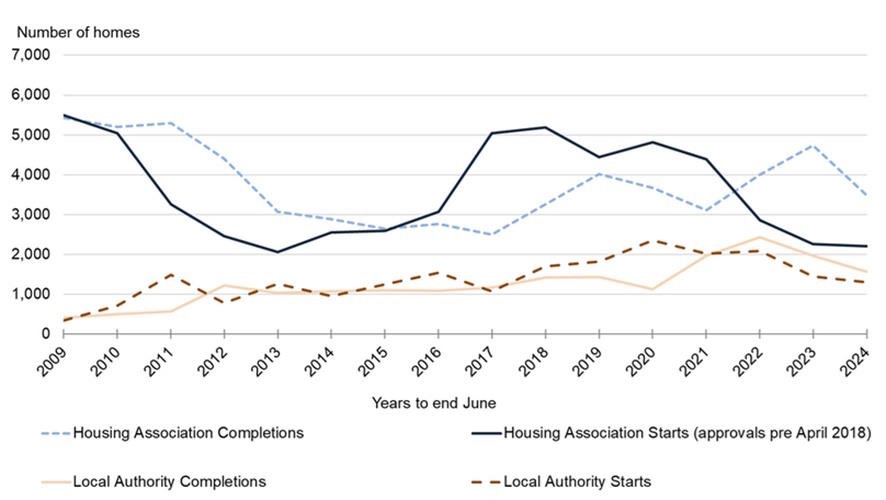

Across Scotland, the number of social housing units started was down by 5% in the year ending June 2024. Private sector starts across Scotland decreased by 19% (Scottish Government (2024c). As can be seen from the following chart, there have been some very noteworthy movements in the numbers of social housing starts and completions – especially in the housing association sector over the last 15 years.

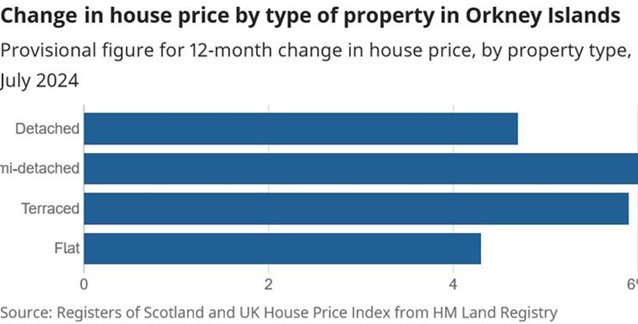

House prices: The provisional average house price in Orkney in August 2024 was £210,624. This was 6% higher than the average of £198,760 in August 2023 (revised) and 5% higher than the Scottish average of £200,000. (Figures provided by Registers of Scotland 2024). Given the relatively low number of sales in islands such as Orkney and Shetland the local figures may vary. Published statistics for April-September 2024, show the average house price was £207,385.

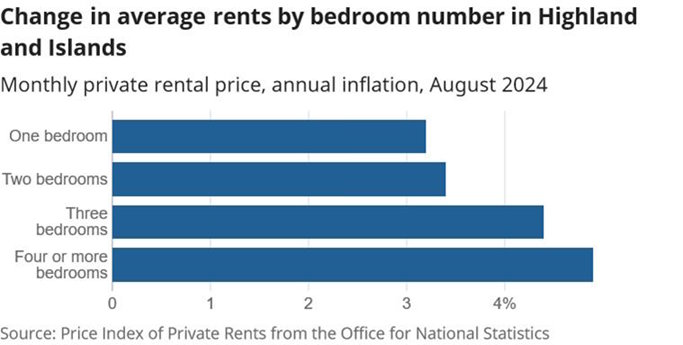

Rental prices: The statistics concerning rents are based on data from the Highlands and Islands. Private rents in this area averaged £676 a month in August 2024. This was an increase from £652 in August 2023, a 3.7% rise. Private rents in Orkney may well be higher than the figure quoted for the Highlands and Islands. Across Scotland, the average monthly rent was £969, up from £901 a year earlier.

While there was only a small difference in the price of buying housing between Orkney and Scotland generally, there was a substantial gap in private rental costs between the highlands and islands and the total for Scotland. This possibly reflects differences in demand for private rental properties in different areas and the capital cost of buildings (for example, the average price of properties in Orkney was 62% of that in the City of Edinburgh) (Scottish Government – Statistics.Gov.Scot 2023).

Rising building costs and government cuts

The cost of building houses has risen significantly over the last few years. Higher interest rates and wage costs, alongside major increases in the price of energy and raw materials, have led to a decline in the profitability of building private houses in several areas and placed a heavy strain on social housing providers. Brexit has been a very significant factor in this. First, an exodus of EU workers following Brexit left the construction industry ‘facing an acute shortage of labourers in some specialist trades and a looming’ (Financial Times 2021). Second, it appears that the cost of construction materials increased by 60% between 2015 and 2022. The Guardian reported that in the EU, ‘where similar pressures including supply chain and Covid problems applied, the cost of materials went up 35% while labour in countries such as Denmark and the Netherlands went up by just over 14%’ (The Guardian 2023). They also report a 30% rise in UK labour costs over the same period. Subsequently, we have also seen further pressure on costs caused by the Russia-Ukraine war.

On top of all this, we must recognise that building on Scotland’s islands is generally more costly than on the mainland. The National Plan for Scotland’s Islands (Scottish Government 2019) reported that house construction on islands is often more complicated and difficult than in many mainland areas ‘due to transportation costs and distances (adding upwards of 30-40 per cent to the price of building)’. They continued:

Regularity and reliability of ferries, weather, availability of workforce, accommodation for workforce and so on can also add to the difficulties. Additionally, participants highlighted that, on some islands, the number of short-term lets or second homes can limit the availability of homes to local residents and workers.

This figure varies between different islands and the size and nature of the development.

By 2024, the cost of building a three-bedroomed house to a ‘mid-specification’ (a standard finish) in Scotland was £2,465 per square metre or £271,140 in total (110 square metres) (BuildPartner 2024b). If we add the additional costs of building on islands, this rises to £352,482. However, this building size is larger than standard social and affordable housing properties with this number of bedrooms. A more realistic figure is probably closer to the level 2 space standard for three-bedroomed, two-floor buildings in England – 87 square metres (Department for Communities and Local Government. 2013 p. 51). The build price for this would be something like £214,415 or £278,791 allowing for additional islands costs. At the time of writing, no new three-bedroomed properties were advertised for sale in Orkney to compare with this estimate. We know the average price of a new build in Orkney was £308,000 in May 2024 (Land Registry 2024) but have no data concerning the size of properties.

The lack of new three-bedroom properties can be largely attributed to building costs above what the market expects to pay for such housing. In other words, local builders are not in a position to make what they see as an adequate profit from constructing such private houses. As a result, they have effectively stopped developing them and appear to be attempting to sell a smaller number of bigger new properties. There were four new four-bedroom properties on the market priced at £320,000, £360,000 (2 houses) and £375,000 at the time of writing [October 11, 2024].

Scottish government financial support has failed to keep pace with the rising cost of building social and affordable housing. Ministers have carried on talking about their target of building 110,000 affordable homes by 2032 (70% for social rental – 10% of which would be in rural and island communities). However, at the same time, they cut the funding for the Affordable Housing Supply Programme (AHSP) for 2024/5 by £163 million or 22% in real terms from 2023-4 (The Scottish Parliament 2024). They also slashed the budget that enabled local action groups to work with partners to deliver collaborative projects in rural and island communities (Scottish Government. 2024e). This reduction of the housing budget took place in the context of a continuing rise in construction costs. There is, in short, a serious deficit in funding for social and affordable housing. As the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, commented to the Finance and Public Administration Committee, ‘the Scottish Government has a pretty good record on housing—its record is much better than those of Governments elsewhere in the UK—and that is to its credit’, but it was ‘baffling that the affordable housing supply programme should be the victim of such a brutal cut’ (The Scottish Parliament 2024).

The UK Government 2024 Autumn budget contained a significant uplift in funding to Scotland. As a result, the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations has, along with other bodies, called for the reverse of the serious underfunding in Scotland’s housing sector in recent years (Scottish Housing News October 31, 2024a). The position will become clearer in December 2024 when the Scottish Government budget is announced for the coming financial year.

Under-occupation and empty homes

A large number of houses in Scotland’s island communities are under-occupied. Na h-Eilean an Iar had the highest percentage of households in Scotland with at least 2 more bedrooms than required (50.6%). It was followed by Aberdeenshire (45.6%), Shetland Islands (44.5%) and Orkney Islands (44.1%). The Housing Report (Scotland’s Census 2024) comments ‘These council areas tended to have lower population density. They had a lot more households living in houses than flats and more bedrooms on average. They also had relatively more people in older age groups. By comparison, in Glasgow just 16% of properties were under-occupied, Edinburgh 24% and West Dumbartonshire 25.3%.

It is not surprising that homes inhabited by older people might be under-occupied. Houses bought or rented for families will accumulate empty bedrooms as members leave to create their own households or join others. The other side of the coin here is, that for those that remain, there may be growing problems around access, the cost of heating and maintenance, and the availability of support. If local, smaller, accessible and convivial housing was available – such as that proposed by Hope Cohousing in South Ronaldsay – some older people might be happy to move and release larger housing units to families etc.

Given the sheer scale of under-occupation in Orkney, it was, thus, surprising that the Local Housing Strategy 2024-2029 (OIC 2024b) failed to address it in any significant way. If things carry on at the same rate as occurred between 2010 and 2020, then the predicted situation in 2040 rises to 91% of Orkney’s 65+ households being under-occupied (Shakespeare Martineau 2024, p.24). While this may not be a particularly reliable figure, it does show the direction of travel involved. Essentially, Orkney – and many other local councils – require an approach that increases the supply of smaller, accessible housing units that are attractive to older people living in larger properties. The latter could then be released to families and groups that can fill the space. The strategy document (and SHIP) does accept that there is a shortage of one- and two-bedroom properties across the County. Sadly, it doesn’t properly recognize the scale of the development needed and what this can do to release under-occupied housing.

An obvious, but not straightforward, question also arises around the number of empty properties in Orkney. Across Scotland in the 10 years up to 2023, long-term empty properties over 6 months increased by 68.4% (Scottish Government 2023c). In Orkney, in 2023, the number of empty properties was recorded as 252 and some 399 homes were registered as unoccupied homes – and exempt from paying council tax. Interestingly the same four council areas head the list for vacant properties as were top in under-occupation. Orkney was fourth again with 5.6% of properties being vacant (National Records of Scotland. 2024b). There was a huge difference, however, in scale. The number of under-occupied properties was nearly 8 times the number vacant. That said a concerted effort to bring some of those vacant properties into use as housing might be helpful. Major questions here concern the number of units that are not worthwhile financially to reclaim; the location of services (mobile signals, power, water etc.), amenities, and employment opportunities; and the nature of the incentives that would be necessary.

Second homes and short-term lets

Like many other island, coastal and rural communities there are a significant number of second homes in Orkney. In 2005, there was a total of 286 such units. This had nearly doubled to 563 second homes in 2022 (Scottish Government 2023a). In 2023 it dropped to 474 units – probably a result of owners reclassifying their second homes as short-term lets (see next paragraph). Many of these properties were in outer and linked island communities rather than Kirkwall. In earlier years, some decrease in the number of second homes may have been related to them being declared as long-term empty properties (OIC 2023 p.37).

Legislation requiring application concerning short-term lets was brought into use in Scotland in October 2022. The figures here relate to the number of applications made by the end of December 2023 (Scottish Government 2024b). By that time 327 applications had been made. This amounted to 415 ‘accommodation units’. These figures do not differentiate between lets for those coming to Orkney to work etc. and those in the County for holidays.

In addition, the Scottish Government has also increased the “Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS) – an extra charge which is added to any Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) on the purchase of a second home in Scotland. It now stands at 6% [It also applies to rental property, holiday homes, and properties used by family and friends even if you don’t charge rent]. Whether any revenue from this finds its way to developing Orkney’s housing is another matter.

The combined total of second homes and short-term lets amounts to more units than was required to handle the growth of households in Orkney between 2011 and 2022 or that required to meet the targets set by the new housing strategy (OIC 2024b).

Homelessness and safety

In Scotland, Shelter reports that in the year 2023/24 there were 40,685 homeless applications made to local authorities. Of these, 33,619 households were assessed as being homeless or threatened with homelessness (Shelter 2024c). In England, Shelter’s figures show that over 3,000 people are sleeping rough on any given night (a 26% increase in 2023). Some 279,400 are living in temporary accommodation (a 14% increase in 2023) – most of whom are families. Around 20,000 people are in hostels or supported accommodation (Shelter 2023). England has the highest rate of homeless households in the OECD (2024).

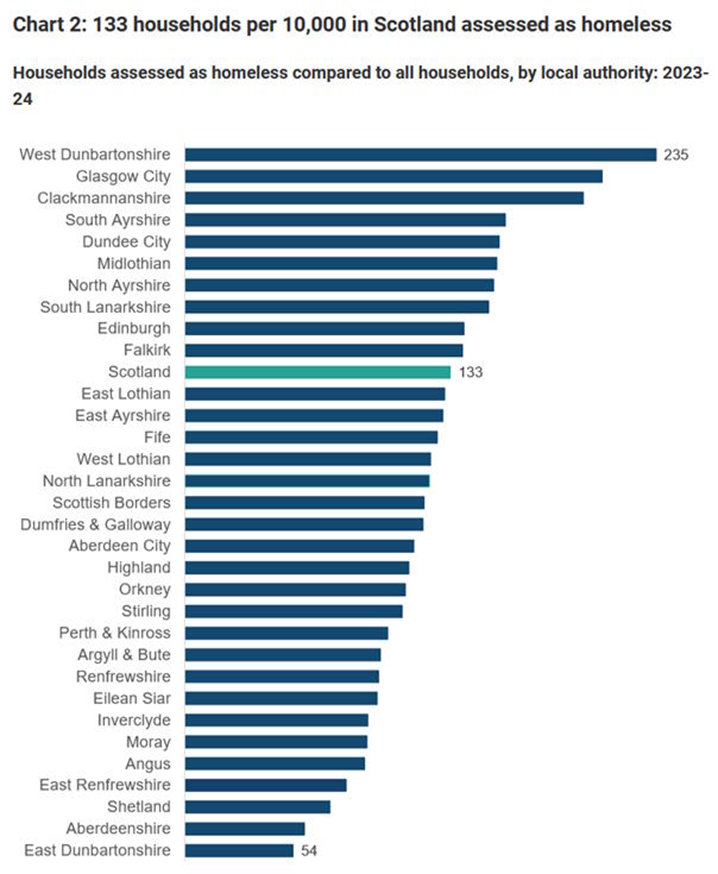

The number of households in Orkney classed as homeless in 2023/4 appears to be around 111 per 10,000 households (or 116 in total). This was close to the figure for the Highlands but below the Scottish average of 133. However, it was significantly higher than Shetland (around 73). (Scottish Government [2024a]).

The number of Orkney households in temporary accommodation as compared to all households was around 68 per 10,000 households (the national average is 64). Shetland was higher at around 108 per 10,000 households – but still a great deal lower than Edinburgh (at 158). Better availability of temporary accommodation may well reduce the number of homeless households in Shetland when compared to Orkney.

A recent from Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) also draws attention to the impact of the shortage of housing. It reports that some people are staying in abusive relationships longer due

to a lack of housing options. On Orkney, for example:

…survivors of incidents such as being attacked by someone nearby have struggled to be transferred to accommodation away from the alleged offender, with as many as 40-50 people applying for each property.

Survivors with health conditions are at a disadvantage in completing applications, and there is no local authority support during the application process. (SHRC 2024, p.47).

Accessibility and care

There is a UK-wide chronic shortage of accessible housing – and fundamental problems around the provision of care for older people, and those with complex needs. As Lorna Campbell, the CEO of Horizon Housing has pointed out, over the last ten years £1.2 billion has been spent due to delayed hospital discharges in Scotland alone (Findlay 2024). At this moment, 31,000 wheelchair users are waiting for accessible homes in Scotland, the number of care home places is reducing, and across the UK we have a social care system that is under-staffed and under-financed. With the further growth of an ageing population, we face a major crisis in provision and care (op. cit.).

When we examine the situation faced by wheelchair users, we find that the lack of accessible homes has a serious impact. They ‘risk injury, loss of independence, or face huge costs for adapting their existing homes or moving into specialist accommodation’ (Habinteg 2023, p.7). Earlier research showed that people with an unmet need for accessible housing ‘are estimated to be four times more likely to be unemployed or not seeking work due to sickness/disability than disabled people without needs or whose needs are met’ (op. cit., Provan et. al. 2016). Accessible homes can have significant positive impacts on wheelchair users’, ‘health, wellbeing, independence, and general lifestyle, with economic and social benefits to the individual and wider society’ (Habinteg 2023, p.7). Research conducted by the London School of Economics (LSE) and the Political Science Housing and Communities research group found that the benefits of new wheelchair-accessible housing are greater than the costs. What the researchers did was to look at the cost of construction and the additional space required to enable accessibility – and then compare this to the savings that could be made in benefits, health costs and support – and the revenue generation through tax where accessibility enables people to work. They found:

- Building an accessible home occupied by a working-age adult wheelchair user creates 4x the benefit compared to the cost.

- Building an accessible home occupied by a later year’s wheelchair user creates 5x the benefit compared to the cost.

- Building an accessible home occupied by a household with a wheelchair user child creates 2.5x the benefit compared to the cost. (Habinteg 2023, p.10).

There is, in short, a strong economic case for developing new wheelchair-user homes. There is also a case for significantly increasing the accessibility of housing generally for older people. However, to do this requires the NHS, local authorities, housing associations, and other bodies to work together.

The position of younger people

In a survey by Young Scot, a significant number of 11 to 25-year-olds indicated that a lack of affordable housing was one of the main issues worrying them about their future (Young Scot 2024). It is certainly a matter of concern for many higher education students today. There is a severe shortage of bed spaces in cities such as Edinburgh (13,852), Glasgow (6,093), and Dundee (6,084) (Chartered Institute of Housing 2024). They also face relatively high rents. A similar problem for students appears to arise in Orkney. It is certainly, the case that there is limited opportunity for them to rent social or private housing at an affordable rent.

For those young people setting out to own their homes, affordability has taken a hammering across the UK. The mean price of a property in Orkney in 2004 was £74,866, in 2023 it was £206,615 (Scottish Government – Statistics.Gov.Scot 2023). During that period the annual inflation rate was 2.9%. If house prices had risen at that rate, the same property would have cost £129,313 (i.e. £77,302 or 40% less) (Bank of England 2024). Using a standard calculator for a repayment mortgage we can see how much more expensive housing is for younger people. Here, we have assumed that the young buyers have raised 10% of the purchase cost. If house prices had increased at the same rate as inflation, our buyers would be paying £647 per month at an interest rate of 4.5%. They would pay £193,990 over 25 years. Instead, they will now pay £1033 per month or £309,957 over 25 years (Money Saving Expert 2024) – nearly 60% more. [At the time of writing the average mortgage interest rate for a 5-10% deposit fixed-term mortgage was between 4.98 and 5.6%. Given current circumstances, it may well not fall much and could bounce back to 6%-plus given ‘shocks’ to the economy].

If we go back to 1981, the average house price in Orkney looks to be around £19,000 (or, using the Bank of England’s inflation calculator – £71,190 today – just over one-third of the current average market price). These figures indicate how different the situation facing younger people today is compared to that of their parents and grandparents. We also need to remember that those living in council houses in 1981, had gained the right to buy their home at a discount of 33% to 50% for a house (there was a larger discount for flats). The 2040 Housing Report prepared by Shakespeare Martineau notes:

The first-time buyers of 2040 are teenagers and young adults living with their parents today, so they will be completely new entrants to the housing market. The consequences of not adequately providing for this segment of the housing market are considerable, and result in many young people moving back into the family home – with delays to household formation and fertility rates in younger adults directly impacted. (2024, p.6)

There is, also, a particular problem around the shortage of affordable homes for young people in Scotland’s rural areas and islands. So much so, that Community Land Scotland has called for legislation to enable young people to have a legal right to live in the community where they grew up. They have argued that the “Right to Live” should be written into legislation, and sit alongside, people’s rights to food and education (BBC News, October 11, 2024). A study undertaken concerning 12 – 25-year-old islanders by Young Islanders Network (YIN) reports that 62% of respondents plan to leave their island when they are older because of a shortage of suitable accommodation (BBC News July 11, 2024). Community Land Scotland’s proposal recognizes that younger people face particular difficulties with housing, but they also stress that they are concerned with local people generally.

A Right to Live is about ensuring that local housing stock is used to meet local needs and that those who want to live, work and contribute to local communities are able to…

Greater regulation of ownership of land and buildings is needed to sit alongside greater investment in rural communities and infrastructure. (Community Land Scotland quoted in Scottish Housing News 2024b)

As with under-occupation, the Orkney Local Housing Strategy (OIC 2024b) does not properly address the scale of the financial mountain that younger people endure and the contribution that social housing provision can make. That said, it is also difficult to find anything significant from the Scottish Government since 2017 concerning the life chances of young people concerning housing (Scottish Government 2017).

What is to be done?

As Alex Diner et. al. have said, we all need affordable, safe, secure homes to build a foundation for ourselves and our families. They continue:

But our housing system is broken, failing to deliver these fundamentals and leading to rising housing insecurity, unaffordability, record levels of homelessness, and surging costs to local government providing temporary accommodation. To resolve the housing crisis, we must dramatically increase the supply of new homes, across all tenures but particularly genuinely affordable homes for social rent, in the places we need them the most. (Diner et. al. 2024)

We now turn to the five key elements needed to create a sensible approach to developing homes and housing in rural, coastal and island communities generally in Scotland. What is proposed here can be equally applied to urban settings. The first component is to place social rental and genuinely affordable housing at the core of our efforts. To this, we add the fundamental need for an emphasis on eco-aware design and construction and the need to avoid retrofitting.

Prioritising a focus on building well-designed, social, affordable and eco-aware rental housing

Since the 1980s and the introduction of the ‘Right to Buy’ social housing, there has been a very significant rise in the cost of housing. This increase can be seen as the main factor in creating the current crisis around renting and buying houses. Before this, as Nick Bano has commented:

Landlords could not command the extravagant rents that we have come to take for granted. Private rents were capped and regulated by law, and the large-scale provision of council housing had diverted a very large number of would-be consumers away from the private rental market altogether. The cost of securing accommodation was much lower because of those cheaper rents (and, for homeowners, consequentially lower house prices), and because of a system that was generally less hospitable to the profiteering activities of landlords, lenders and speculators. (2024, Introduction)

With the loss of millions of social rental homes in Britain to the ’Right to Buy’, it has meant that people have often been driven into the more costly private rental market. This can be extremely stressful – particularly where tenants are not covered by the sort of legislation that exists in Scotland. ‘The business of private renting is simple’ Vicky Spratt argues, ‘private renters add to their landlord’s wealth while (usually) diminishing their own’. Furthermore:

… our cultural conflation of homeownership with success and renting with failure imbues an unshakeable and corrosive shame. Being caught in the rent trap is Sisyphean: each month you work to earn money to pay rent on a home you will never own and from which you could be evicted at any time. (Spratt 2022, Chapter 6).

As we have already seen, many younger people are now effectively barred from home ownership. They have become, in Chloe Timperley’s words ‘Generation Rent’ (2020).

Not all private renting takes this form. The Scottish Government has both stopped the ‘Right to Buy’ (in 2016) and legislated to create a more robust private rental policy. A significant number of community-based initiatives in Scotland have, thus, been able to offer private rental housing that addresses local needs with rents held at local housing allowance levels. They can also provide a level of tenant protection similar to that within social housing. In Wales the ‘Right to Buy’ was ended in 2019 – and it looks now like the first major cracks in the policy are appearing in England. New council housing may be removed from right to buy scheme (Guardian, November 7, 2024). Rachel Reeves had also announced measures in the Autumn Budget to allow councils to keep all the money they receive from social housing sales. This was a policy that the previous Conservative government had followed for two years up to March 2024.

Unfortunately, over the last decade or so, rather too many politicians have failed to admit the obvious – owner-occupation has peaked. The percentage of households that could call themselves owner occupiers peaked in England in 2003 (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. English Housing Survey 2021-2 / Gov.UK 2024) and in Scotland in 2006 (Scottish Government 2024g]. As Julian Richer (with Kate Millar) have pointed out:

For there to be a surge in homebuying, young people’s wages would have to shoot up. Or house prices would have to plummet, or the taxpayer would have to finance huge state ‘help to buy’ subsidies. The only other way would be for families to cripple themselves financially…

We need to recognize that providing good-quality, rented housing, let on secure tenancies, at rents people can afford, is the only way to address society’s immediate, urgent, needs. (2024, Introduction)

Since 2011 there have been attempts to shore up owner occupation with initiatives such as ‘Help to Buy’ – but these efforts fall into a similar trap as the ‘Right to Buy’. They both cost the state a significant amount of money – the first because it is a rather large subsidy, the second because in over 41% of cases, it eventually led to inflated private rents which often had to be subsidized by increased housing benefits (which in England amounted to over £23 billion in 2022) (Fitri 2022).

Many people have, in short, experienced four decades of deeply problematic housing policies. We need to drop the fantasy:

… that we will ever reach a nirvana of home ownership for all, and acknowledge that millions of people need homes that are developed in such a way … that residents can have tenancies at rents they realistically afford and which will not increase beyond their means (Julian Richer with Kate Millar 2024, Chapter 5).

Priority, therefore, needs to be given to social and truly affordable rental housing. By affordable I mean housing that is in the reach of people with low and average incomes and in line with Local Housing Allowances (LHAs). We need to move away from a system that encourages house price growth. As Nick Bano has argued we have to start decommodifying housing:

As a country, we have bet the farm on house prices, and successive governments have been understandable cautious about altering the laws designed to encourage homes to become more expensive. But the scale of the harm of this system can no longer be denied. (2024, p. 208)

This involves emphasizing the ‘social’ in social housing and significantly expanding the number of homes owned by, and provided for, local communities. It also entails designing neighbourhoods and projects so people feel safe, can easily access services, and engage with neighbours.

Building well-designed social housing

Looking at the building statistics for Scotland, it is first necessary to focus on social housing rather than the social housing and affordable housing figures as they include ‘affordable’ homes that are outside our definition of affordability. What we find is, that in the period 2011-2023, housing associations built 45,465 homes (or just under 4000 pa) and local authorities completed 18,226 homes (just over 1400 pa) (Scottish Government 2024c). Since 2021, the Scottish Government has sought to realize a route map with the aim that all have a safe, good quality and affordable home that meets their needs where they want to be. Unfortunately, they continued to use the term ‘affordable’ but at least set a social rent target of 70% of the 100,000 homes promised by 2032 (Scottish Government 2021). This target was then increased to 110,000 homes. Ten per cent of the new homes were to be ‘in our remote, rural and island communities’ (Scottish Government 2022).

When turning to the building statistics for England we need, again, to strip out so-called ‘affordable’ housing and focus on social housing. Over the same period as above, housing associations started 307,576 homes (close to 23,660 units per year) and local authorities began 22,200 homes (around 1710 units per year) (figures from the Office for National Statistics 2024b). Funding for social housing in England was largely routed through housing associations during this period of Conservative-led government. When we adjust these figures to reflect the different national population sizes in 2021-2022, we can see that the English government supported housing associations to build the equivalent of 65% of the houses constructed in Scotland. For homes built by local councils in England, this figure dropped to around 12% of the Scottish figure. The overall rate at which social housing was built in England was under half that achieved in Scotland.

Sadly, one of the elements often missing from the way governments and local authorities approach social housing is serious consideration of the quality of design involved. It is easy to get the feeling that the job, in their eyes, is just to put a roof over people’s heads. One of the fascinating things about the development of many of the new towns from the late 1940s through to the 1960’s, is the care with which neighbourhoods and housing were often designed. There was, often, variety in the housing, an emphasis on green spaces, and a concern for creating neighbourhoods. This certainly wasn’t the case in a lot of urban development, particularly when it came to the planning and execution of tower blocks and estates. There were some excellent, and carefully designed developments, that looked to enhance the life and experiences of tenants but sadly they were not in the majority.

Here, there is something that we can learn from the approach taken by Hjaltland Housing Association and the architect Richard Gibson in Shetland. As Rowan Moore put it:

In the northernmost British Isles he created thoughtful, well-made places for people to live. His projects respond to Shetland’s windy climate and steep landscapes, and to its hardy, constructive, communal spirit. Some form sheltered enclaves with sturdy masonry, others are timber structures that light up the landscape with their strong colours. Now, when the need for genuinely affordable homes is pressing, and the quality of their design is a crucial question, Gibson shows how it can be done. (Moore 2024)

One of the striking things about their schemes is the variety of the buildings they plan, the setting for them, and the attention given to communities across the length and breadth of Shetland (click to see them mapped). That said, there has been a strong demand for, and emphasis upon, developing housing in Lerwick. In general, the social housing in Shetland is, according to the Scottish Human Rights Commission:

… regarded as the best quality by members of the community. Homes there are built with thicker walls and better insulation. The Commission observed the some of social housing on Shetland first hand, and suggests that it may be a model for other local authorities to replicate. (2024: 45)

As Matilda Agace, the policy lead at the Design Council has pointed out,

The truth is that most new development isn’t good enough, 75% of new housing schemes are poor or mediocre… (C)ampaigners are calling for an ambitious housebuilding agenda, but we need to be equally ambitious about the design quality and climate credentials of the homes Britain creates. (quoted by Phineas Harper 2024).

There is a robust case in Scotland, and across the rest of the UK, for increasing the amount of social housing currently available – but it has to be done in conjunction with other elements. These include reducing under-occupation, attending to design, and ensuring that existing and new housing is safe, fit for purpose, and eco-aware.

Eco-aware housing

A large amount of existing housing has been built to poor standards. Scanty insulation, dangerous cladding and cement mixes, problematic heating arrangements, accessibility issues, and basic problems with design – plague too many properties. Alongside the housing emergency, we are also in the midst of a climate emergency. While there are still some who deny or dispute that we are in deeply perilous times on planet Earth, the vast majority of scientists in the field would endorse the opening statement of The 2024 State of the Climate Report:

We are on the brink of an irreversible climate disaster. This is a global emergency beyond any doubt. Much of the very fabric of life on Earth is imperiled. We are stepping into a critical and unpredictable new phase of the climate crisis… Tragically, we are failing to avoid serious impacts, and we can now only hope to limit the extent of the damage. (William J Ripple, Christopher Wolf et.al. 2024)

Governments within the UK have generally recognised the situation and taken some steps towards containing the climate emergency. However, they have not followed through with the speed and rigour needed. Thankfully, the Scottish Government has identified the need for new building standards that reduce emissions and energy usage. They have been working towards a Scottish equivalent of Passivhaus. Unfortunately, the speed of travel in this area is painfully slow.

To get an idea of what this standard might involve we can turn to the Passivhaus Trust. It looks for the following elements:

- accurate design modelling using the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP)

- very high levels of insulation

- extremely high-performance windows with insulated frames

- airtight building fabric

- ‘thermal bridge free’ construction

- a mechanical ventilation system with highly efficient heat recovery (Passivhaus Trust, undated)

click to see a short video

An Orkney example of this approach can be found in Hope Cohousing’s design and specifications (less the mechanical ventilation).

Across the UK, we are seeing an increasing number of local authorities and housing associations looking to Passivhaus standards – and building social and affordable housing that incorporates the above features. The obvious advantage is that it reduces emissions and global warming and expenditure on energy. As Yogini Patel from the Passivhaus Trust puts it, customers ‘don’t have to choose between heating and eating so they’re less stressed out mentally and physically’. (France 2024)

There is now a growing body of evidence that shows that housing built to Passivhaus standards:

Reduces rent arrears and void periods, which benefits councils and housing associations and de-risks the investment while also supporting residents.

Can have significant health benefits. One example here is a reduction in medications as residents are not having to deal with damp housing.

Gives residents better fuel security. (France 2024)

One of the reasons given by housing providers for not adopting these standards is that it would add significantly to the cost of construction. There are two answers to this. First, building to lower standards will, in the longer run, inevitably be more expensive to housing providers and disruptive to tenants. The cost of retrofitting will quickly exceed the amount saved by building to lower standards.

Second, the price difference between Passivhaus and traditional buildings is decreasing. Lessons are being learnt from a chain of projects. Research by the Passivhaus Trust shows that achieving the standard now costs 8% more than building to existing regulations. Significantly, Exeter City Council says their Passivhaus projects are coming in 4% cheaper than those using standard building regulations (op. cit.). Other councils involved in Passivhaus developments include York, Salford and Norwich. However, evidence from Scottish projects shows a higher cost of building to Passivhaus standards than these English projects. This could be largely attributable to a relative lack of experience on the part of builders concerning this sort of development (Phil Lewis, Randall Simmonds – Passivhaus Trust 2024).

Orkney and other councils across Scotland need to follow the example of some English local authorities and commit now to building housing to near-Passivhaus standards. This does involve developing expertise and designs that allow them to hit the ground running. Building accessible and welcoming houses and localities that invite older people, in particular, to downsize needs to be a priority. It will release larger properties for families, groups of people with shared interests, and development as flats. It is to this that we now turn.

Developing accessible and welcoming homes and localities that invite older people, in particular, to ‘rightsize’ and release larger properties for families and younger people

The housing strategy for Orkney recognizes the need to build or acquire more one and two-bedroomed properties. Unfortunately, it does not provide a detailed rationale for this, the number of properties likely to be required, and an overall development plan. We do learn that an ‘estimated 50-70 wheelchair properties are required over the next ten years, based on varying assumptions on health outcomes’ (OIC 2024 p.29). This is probably an understatement of potential demand given the likely growth in the numbers of over 65-year-olds.

We are also told there is a ‘very high demand and unmet need for care at home’ (op. cit.). There was a little more discussion in the earlier Strategic Housing Investment Plan (SHIP) (OIC 2021). It included the projection that, by 2041, 26% of the population would be over 70. There was also an appreciation of ageing as a process and the need for action before issues around mobility, social interaction, community engagement and care arise. This received little attention in the 2024 strategy document. Sadly, this is symptomatic of something that happens across Scotland (and the UK) – the absence of integrated thinking and services that connect health, care, social work, education, housing and community development.

As we saw earlier, younger people are significantly disadvantaged in the housing market. Action on any scale requires that new one- and two-bedroom properties be created as starter homes for younger people and as rightsizing opportunities for older people. It also entails that a significant number of larger properties are acquired by councils, housing associations and community development trusts to be, for example:

• let to families or people interested in collective living;

• converted into flats; and

• remodelled as residential settings for students and workers.

Given the scale of under-occupation in Orkney and many other rural and island settings, there might be a more limited need for building larger social housing e.g. for families with three or more children or that include ageing relatives. The big question is whether older people can be attracted to move from their homes into smaller units. Here, we explore one particular way to develop housing for older people, but it can be equally used for younger people. It is just one example of what needs to be done – one that looks to community-led initiatives.

The proposed Hope Cohousing (HCH) project in St Margaret’s Hope shows the nature of development that needs to happen for older people. It has:

Six one and two bedroomed single-storey homes all of which are wheel-chair accessible and built to near Passivhaus standards.

Spaces that enable residents to meet, eat, and work together. These include a covered walkway to access all the properties, a meeting room and a shared garden.

Good access to local shops, the surgery, bus routes, the hall, church, and other facilities. All these are within a five to ten minute walk.

In other words, it creates a setting where people can enjoy an active old age in the heart of their community. It is a development that can be replicated in other villages and island communities and should easily meet recent Scottish Government guidance for local living and 20-minute neighbourhoods (Scottish Government 2023b). St Margaret’s Hope has reasonably good public transport links to Kirkwall, the hospital and Stromness. Sadly, many parts of Orkney are poorly served in this respect and become more problematic for everyday living as people age or suffer illness and mobility issues.

Cohousing projects also have further benefits. Day-to-day matters are handled by residents, and they are expected to look out for their neighbours. There is also a growing body of evidence that shows cohousing:

Reduces social isolation and loneliness.

Fosters mutual aid, activity, and wellbeing.

Adds to the supply of affordable housing.

Strengthens local community life.

Can have significant health benefits (Smith 2022, 2024).

Hope Cohousing is a community-led project developed by people with a history of involvement in local initiatives in South Ronaldsay and Burray. They were all living in housing that was starting to pose significant problems as they aged. This included issues with access, steps and stairs, isolated locations, dampness, and the high cost of heating. They set up a community interest company to create the first fully rental cohousing project in the UK (with rents within the Local Housing Allowance for Orkney). The development is now shovel-ready but needs to finalize its funding package. HCH works under the umbrella of the Communities Housing Trust (CHT) – a registered charity and social enterprise focused on building sustainable rural communities across central and northern Scotland. It has considerable experience setting up and hosting small, local housing projects.

Initiatives such as this can have a significant knock-on effect. They are an example of self-help that can benefit generations after them. At the same time, they free up properties for families and younger people or for development. This sort of project will not appeal to all. Some may want to move to an urban centre like Kirkwall with closer access to a range of shops and the hospital. Others may not like the idea of being involved in organising community activities or having to look out for neighbours.

Orkney, and other councils, need to commit – where possible and appropriate – both to community-led projects such as this and to twenty-minute neighbourhoods. In Orkney’s case, this entails revisiting its tendency to build at the periphery of urban centres without fully ensuring that key resources such as shops and surgeries are within a 10-minute’ walk (each way). Regarding older people, the local authority is also currently moving towards building housing targeted at them close to the three main care homes in the County. This is so that home-based care requirements can be met with minimal travel etc. Unfortunately, it places the administrative need to save money above the benefits to older people of living in the heart of the communities that they are familiar with – and the quality of life of islands such as South Ronaldsay.

Containing and reducing the number of second homes and holiday lets, to increase the supply of homes available to local people and the amount of temporary/short-term accommodation for incoming workers and those experiencing homelessness.

When holiday homes and second homes saturate communities, they can cause significant harm to the local economies in the long run (Cash 2022). They can also trigger serious damage to village, small town, and island life – as seen in places like Cornwall, and are now in Orkney. First, they replace neighbours with visitors – people who are there either, for only part of the year or for a very short time. Second, out-of-season they can create ‘ghost towns’. The population of villages and islands is reduced, with a knock-on effect on daily life, community cohesion, and the viability of local shops and services. Third, they reduce the supply of housing to local people by pushing up the cost of buying and renting property. As a House of Commons Library briefing put it:

(T)here are concerns that where the number of second homes comprises a significant proportion of the housing market, it can reduce housing supply and push up house prices to unaffordable levels for local people. (Grimwood et. al. 2022)

Orkney has also witnessed a huge increase in the number of tourists, some fleeting – but in huge volumes – such as those from cruise liners; some longer lasting – such as holidaymakers (recently, particularly those in camper vans). There is, as James Cash (2023) has noted, an upside and a downside:

The ability to let homes to tourists can channel considerable cash into local economies. Vacationing families spend more on food and leisure activities than local households, benefiting local businesses.

But the popularity of second and holiday homes is often concentrated around the coast and areas of outstanding natural beauty. National parks and geography limit the infrastructure needed to comfortably serve holidaymakers and native dwellers. Roads are often too narrow for increased traffic, while parking capacity can be insufficient at peak season, to the detriment of those who live and work in those communities.

On top of all this, people are coming to work in the County. The upside is that many are undertaking key roles in education, health and welfare, the development of infrastructure, and so on. The downside is that, at the moment, the supply of new and reclaimed housing is now not keeping pace with this.

Many of us will know of people who cannot find homes to rent – or are not in a position to buy housing. Up to around the onset of the Covid epidemic, Orkney Islands Council (OIC) and Orkney Housing Association (OHAL) were broadly able to build enough social and affordable homes to mirror the growth in demand and to mitigate a large part of the growth in second homes and short-term lets. Since then, there has been a dramatic fall in building rental homes and affordable houses for sale. However, in the latter, there might be marginal growth over the next year or so due to a possible drop in interest rates. That said, it may be that housing prices do not increase much above the rate of inflation over the next decade. It is difficult to estimate, for example, the impact of fundamental shifts in the labour market due to AI, new technologies, and geopolitical change will have on the property market.

Actively supporting and financing community-led initiatives

Some of the most interesting Scottish housing initiatives have been led by local development trusts and based in island communities. Whether it is:

Mull and Iona’s pioneering the use of modular home and kit houses,

Arran’s focus on solving the shortage of affordable housing on the island and combating the impact of tourism, or

Shapinsay’s concern with developing housing, community provision, ferry services and other projects such as The Smithy Café

… there is a lot of innovative work going on.

Click to view this five-minute video outlining the work of Shapinsay Development Trust

Development trust members generally have a better understanding of local people’s feelings and needs. They also have specialist knowledge and a stronger incentive to get things done. Such trusts also tend to act as private rather than social, landlords. This means they can use points systems etc. to target particular groups of tenants that are vital to, and necessary for, island or local life. This has included, for example:

Families with young children – so that local schools are viable.

Experienced ferry operatives to keep the lifeline ferries operating.

Professional practitioners such as teachers and nurses.

Accessible housing for older people.

People already living and working on islands (much as is the case in Community Land Scotland’s argument for the “Right to Live” where you have been brought up).

Much of Orkney is not covered by local development trusts. In Burray and South Ronaldsay, where Hope Cohousing is based, there was, until recently, an inactive trust. Unlike most of the other Orkney Islands trusts, it did not have financial support from local wind turbines, nor was it a registered charity that could apply for a wider range of funding. The record of island development trusts suggests that local authorities must encourage the development of such trusts generally, and significantly increase the amount of public money that supports their work.

There is also a role for major financial support for other community organizations developing initiatives and delivering services. This includes village halls and community associations, housing projects such as Hope Cohousing, and local innovative schemes such as the community buy-out in South Ronaldsay of the Tomb of the Eagles.

Encouraging people to view houses as homes rather than investments and increasing the proportion of new social and truly affordable rental properties

The entry price for buying housing has nearly tripled in real terms since 1981 – and this is now limiting the ability of young people to become homeowners. The main things that fuelled the rush of tenants to buy council housing were the discount offered by Margaret Thatcher’s UK government and the growing notion that owning something somehow set people above renters. Houses could also be seen as investments and assets. One of the problems here is that ownership can also make us selfish. As Rowan Moore (2023 Introduction) put it, ‘property does things to your mind’.

[Ownership] can also make you selfish. You might oppose wind turbines, or a treatment centre for people who use narcotics, or low-cost housing being built nearby, or indeed any housing that affects your view. You might discourage those whom you consider to be the wrong sort of people from coming to your street… [Y]ou may even want to exclude people on the grounds of race. In some places, at some times, this is exactly what has happened, with deliberation and method.

The growing significance of home ownership also ran in parallel – and was linked to – other social and economic trends that placed less emphasis on community and more on individual achievement. As a result, economic inequality has grown significantly in Scotland and the rest of Britain, and a larger number of people live in poverty. Significantly, the Right to Buy scheme has been a factor in this – 41% of the properties sold via the scheme are now in the hands of private landlords. They are commanding much higher rents from tenants than would be the case in social housing. It has, in short, had a devastating impact on our housing system (New Economics Foundation 2024).

As we have seen, younger people generally suffer the most in the housing market. As a result, we are seeing a growing recognition that home ownership will not be possible for many in their generation. Here are some key statistics:

The proportion of those aged 25-34 who ‘own’ their own homes is 38% – down from 51% in 1989 (this includes people with mortgages) (Feeney and Colvile 2024).

Today the average house in the UK costs almost nine times the average salary, the worst affordability ratio for the past 150 years. The important point to bear in mind here is that the maximum amount that can be borrowed for a mortgages is usually 4.5 times a person’s salary. As we have seen, the average house price in Orkney was £207,385 in the six months leading up to September 2024. To get a mortgage this would involve a deposit of just under £20,740, and for the buyer to be earning nearly £41,500 pa. The average (mean) wage in Scotland at this point was £31,697 per year. The average wage for full-time workers was £36,508 per year, while for part-time workers it was £14,661 per year (The Expatrist 2024).

Almost three-quarters of retired households in Britain now own their home outright, compared with less than 30% where the main earner is self-employed and less than 20% of those who are employees (Office for National Statistics 2022)

The Resolution Foundation’s (2023) intergenerational audit concluded that young people were far less likely than previous generations to own their homes. They were also more likely to find themselves in the private rented sector.

As we saw earlier, housing may become a less profitable asset over the coming years – particularly if salary levels stagnate or drop. First, demand for housing for owner-occupation may continue to decrease. Furthermore, if housing associations and local authorities receive the funding they should from central governments, and then build energy-efficient and attractive neighbourhoods, the attractiveness of renting homes will get a further boost.

Second, there is also a good chance that the dwindling income of many renters may also start to impact the private rental sector. As Nick Bano (2024 Chapter 7) has argued:

… the current sharp shocks to household finances have come on top of more than ten years of austerity and wage stagnation, during which many people already sacrificed their living standards to meet their housing costs…

With the national economy based in no small part on steadily rising rental yields, and a cost-of-living-crisis in which people are genuinely worried about surviving, conditions have rarely been more auspicious for economic melodrama.

An important additional element is the possibility that governments will look more closely at the cost of significantly expanding social housing. A huge saving could be made in the payment of housing benefits if it was going to social rather than private rental housing.

Thanks to work undertaken by the Centre for Economics and Business Research (Cebr) for Shelter and the National Housing Federation (NHF) we now have some indication of the need for, cost and socioeconomic value of generating social homes (Cebr 2024). This report argues that 90,000 social rental homes must be built annually over ten years to combat homelessness and clear social housing waiting lists in England. The research worked on the assumption that the upfront cost of each unit built would average around £254,240. If we scale everything down to the nature and size of the build that the local authority has suggested is needed each year in Orkney, then we can, as a starting point, work on a similar price and multiply it by 40. This would amount to a spend of around £10.17 million in the first year. If we use the Cebr model, such a development would directly create around 62 full-time equivalent jobs. On top of this it would support jobs along the supply line connected with the goods and materials, and additional services, needed for construction – and via the spending of employees in the wider economy. The potential number of jobs created across all these elements amounts to around 157. There are also ongoing benefits from managing this growing number of properties over the following years. Cebr (2024) found that the net positive economic and social impact in England would, in total, be £51.2 billion over 30 years.

Conclusion

In what follows, we summarize some of the key things that the Scottish Government and local authorities will have to attend to.

Central and local governments need to unhook themselves from their over-reliance on private sector provision – particularly around affordable housing provision.

First, as we have seen, younger people are increasingly unable to buy their own homes because of the disproportionate rise in the valuation placed on housing in relation to what they earn. Government schemes such as the “Right to Buy” and “Help to Buy” have worked to increase house prices rather than improve affordability. Brexit has exacerbated matters by increasing the cost of materials – and the shortage of skilled construction workers.

Second, the ‘affordable’ housing produced by the private sector has too often been substandard – and potential buyers recognize this. Research from the Chartered Institute of Building shows that 45% of a sample of UK adults reported that they had no trust, or a low level of trust in housing developers delivering new-build homes to a high standard (2023, p.9). When asked, ‘Which, if any, of the following best describes your opinion of new-build housing?’, the top four results were:

- overpriced (48%)

- lacking character (41%)

- modern (34%)

- poor quality (32%) ( cit.)

The average property, according to thisismoney.co.uk now ‘comes with as many as 157 defects, up by 96 per cent from 80 in 2005, according to specialists BuildScan’.

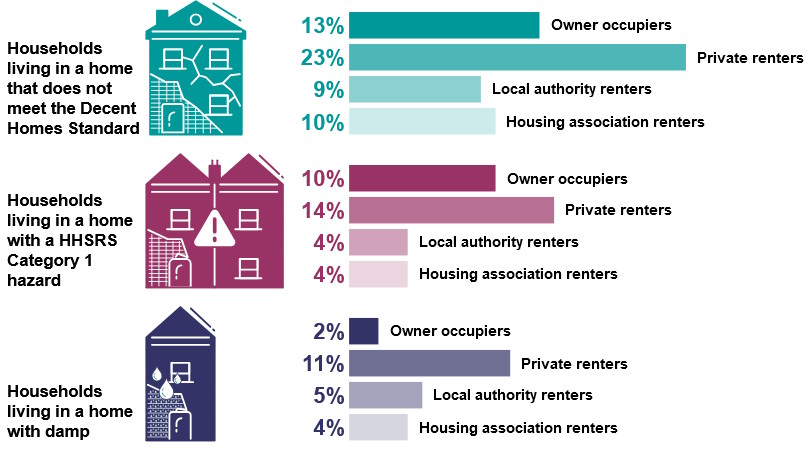

Third, housing in the private rental sector is both significantly more expensive than the social housing sector, and of poorer quality. As we can see from the diagram below from the English Housing Survey 2021-22 (2023), private renters are much more likely to live in a home that does not meet the Decent Homes Standard and in damp homes.

There is a need to prioritise – and focus on building – well-designed social, affordable, eco-aware rental housing.

As has already been seen, local and central governments in the UK will only be able to tackle the current housing emergency over the next decade or so by significantly increasing the amount of social and truly affordable rental housing. Alongside this, runs the fundamental need for housing to have a high level of insulation, triple glazing and be powered by eco-aware energy. However, all this involves policymakers adopting a different mindset. Rather than 30% or 35% of households in Scotland living in social and truly affordable rental housing, it rather looks like the target could be more like 50%. This means that both central government and local councils must examine their priorities. One obvious area is to investigate questionable capital projects. One example from Orkney is the proposal to build a deep-water quay in Scapa Flow. Initially estimated to cost £115 million it has now shot up to £275 million (The Orcadian. October 17, 24). That amount, incidentally, if spent on housing, could create well over 1000 new homes and be of significant economic and social benefit to the County – as the Centre for Economics and Business Research (Cebr 2024) has shown.

The need to support rightsizing

The high levels of under-occupation in several rural and island communities require intervention. The possibility that by 2040, for example, over 90% of Orkney’s 65+ households will be living in under-occupied properties should result in a radical shift of emphasis in housing policy. Sadly, there appears to have been a failure in Scotland to recognize the problems that could be involved with this in some (possibly a lot of) local authorities. There also might be a degree of nervousness on the part of policymakers to act so that both older people and younger people with families have, and choose, the sort of housing (and neighbourhoods) they need. It is an area that needs to be approached with sensitivity and care and backed up by a significant investment in building housing. It also entails listening to what local people are saying.

Central and local governments must actively support and finance community-led initiatives

The current housing crisis can only be solved if councils and national governments attend to what local people think about their experience of living where they do, and how things can be improved. As we have seen, local development trusts have had some success in fostering housing and other developments that sustain and improve communities, and enable them to retain services and valued ways of living. The record of development trusts indicates that local authorities must encourage the development of such bodies and ensure that they remain linked to particular villages or areas that have clear identities for local people. Within these areas, there may also be discreet local initiatives. Governments and local authorities will also need to increase the amount of public money that supports the work of these trusts and initiatives.

Local authorities will have to make painful decisions. For example, many highland and island councils will need to focus on creating homes and sustaining basic services such as health for local people. The growing scale of the housing problem is such, that some local authorities will have to contain and even reduce tourism – particularly where it involves short-term lets and second homes. This will also require the Scottish Government to enhance financial mechanisms and local planning powers to penalize certain forms of short-term lets and second homes.

References

Bank of England. (2024) Inflation Calculator. [https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator].

Bano, N. (2024). Against Landlords. How to solve the housing crisis. London: Verso.

BBC News (2016). Housing bodies welcome end of Right to Buy in Scotland. [https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-36923471. Retrieved October 4, 2024].

BBC News. (2024a). Call for young to have legal right to live where they grew up. [https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cn4yg4wk8y0o. Retrieved October 12, 2024].

BBC News. (2024b). Teenage islanders worried they won’t have a house in future. [https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cy79q72xl87o. Retrieved October 30, 2024]

BuildPartner (2024a). Will UK construction costs fall in 2024? [https://buildpartner.com/will-construction-costs-and-material-prices-fall-in-2024-a-forecast-for-uk-construction/. Retrieved October 8, 2024].

BuildPartner (2024b). Average Building Costs Per Sq M For 2024 – A UK Guide. [https://buildpartner.com/average-building-costs-per-sq-m-for-2024-a-uk-guide/. Retrieved October 9, 2024].

Cash, J. (2022). Ghost town: the effect of second homes on communities, Modus – Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS).

Cebr. (2024). The economic impact of building social housing: A Cebr report for Shelter and the National Housing Federation. February 2024. [https://www.housing.org.uk/globalassets/files/cebr-report-final.pdf. Retrieved November 1, 2024].

Chartered Institute of Housing. (2024). Thousands of students in Scotland at risk of homelessness. (September 17, 2024) [https://www.cih.org/news/thousands-of-students-in-scotland-at-risk-of-homelessness/. Retrieved October 12, 2024].

Department for Communities and Local Government. (2013). Housing Standards Review. [https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/230251/2_-_Housing_Standards_Review_-_Technical_Standards_Document.pdf. Retrieved October 10, 2024].

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. (2022). English Housing Survey 2021 to 2022: headline report. [https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-housing-survey-2021-to-2022-headline-report/english-housing-survey-2021-to-2022-headline-report. Retrieved November 1, 2024].

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. (2023). English Housing Survey 2021-22. [https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-housing-survey-2021-to-2022-housing-quality-and-condition/english-housing-survey-2021-to-2022-housing-quality-and-condition. Retrieved November 5, 2024].

Diner, A. Tims, S, and Williams, R. (2024). Building the homes we need. The economic and social value of investing in a new generation of social housing. London: New Economics Foundation. [https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/Building-the-homes-we-need-web.pdf. Retrieved October 22, 2024].

Dorling, D. (2014). All that is Solid. The great housing disaster. London: Allan Lane.

Expatrist, The (2024) What’s the Average Salary in Scotland? A 2024 Overview. [https://expatrist.com/what-is-a-good-salary-in-scotland/. Retrieved October 21, 2024].

Feeney, M. and Colevile, R. (eds.) (2023) Justice for the Young. London: Centre for Policy Studies. [https://cps.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/CPS_JUSTICE_FOR_THE_YOUNG.pdf. Retrieved October 21, 2024].

Financial Times. (2021). Exodus of EU workers leaves UK construction industry facing shortages. [https://www.ft.com/content/6ddd9b7e-781c-477e-87b2-d4fd283362da. Retrieved October 9, 2024].