William Godwin on education: ‘Refer them to reading, to conversation, to meditation; but teach them neither creeds nor catechisms, either moral or political.’

contents: introduction · life · anarchism · education · references · links · how to cite this piece

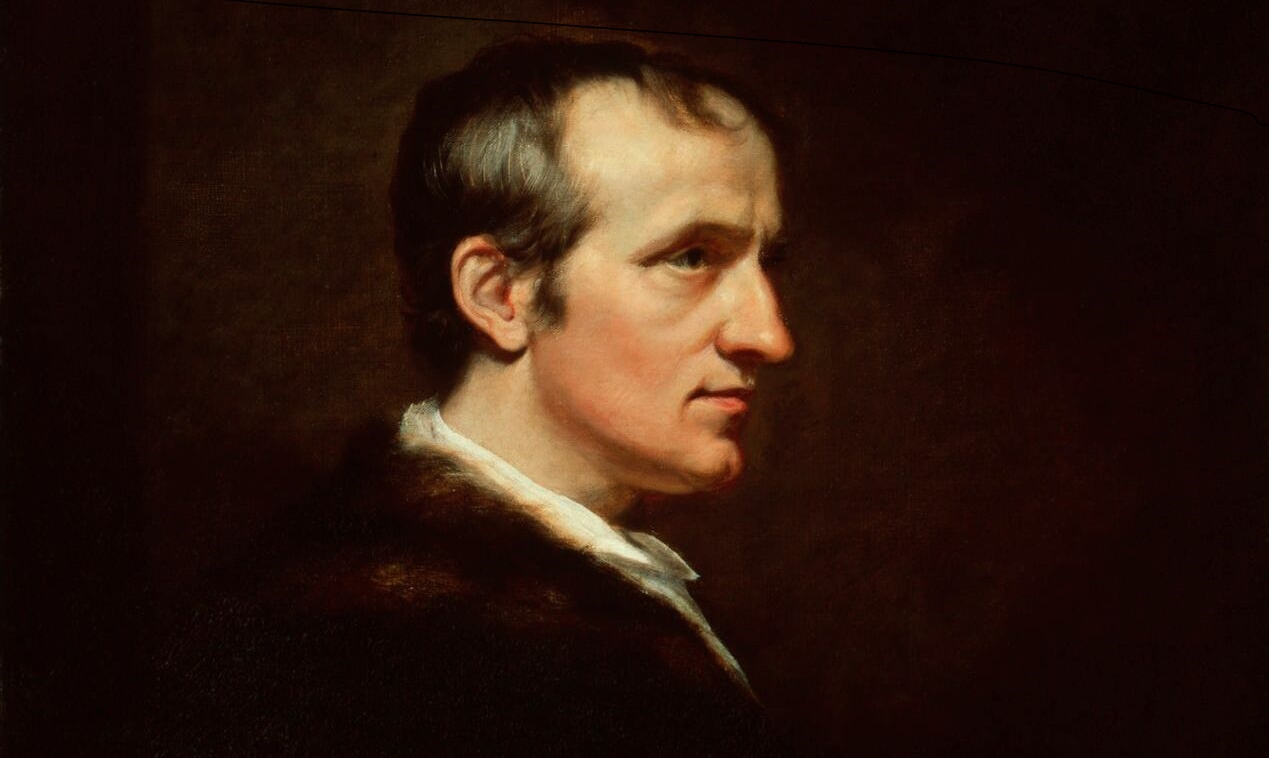

William Godwin (1756 – 1836) was the first writer ‘to give a clear statement of anarchist principles’ (Marshall 1993: 191). He was one of the first English-language writers to recognize the threat of state-controlled education and to set out the qualities of an alternative, free, education. Today he is perhaps best remembered as the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft (who wrote the feminist classic: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman -1792, the father of Mary Shelley (the author of Frankenstein – 1818) and the father-in-law of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (who was influenced by his radical libertarianism).

Life

William Godwin’s life certainly had its ups and downs. Born into a family of Dissenters, he was individually (and sometimes brutally) tutored by Samuel Newton, an extreme Calvinist. He later joined the Dissenting Academy at Hoxton (aged 17). Initially wishing to enter the ministry, he came to describe himself as a ‘complete unbeliever’. His conservatism turned to republicanism He seems to have reasoned his way through to these conclusions. His radicalism came from an encounter with writers such as Rousseau and political events such as the American War of Independence.

Having turned away from the ministry William Godwin earned a living through writing and teaching. The former included short novels, biographies and newspaper pieces. In response to the fierce debate and argument around the French Revolution (from 1789 on), Godwin wanted to set out a properly philosophical and principled statement of political theory. The result was An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice which appeared in 1793. It brought him momentary fame and some wealth (a thousand guineas). He followed it up in 1794 with a novel The Adventures of Caleb Williams. Peter Marshall describes it as ‘a gripping story of flight and pursuit designed to show how “the spirit and character of the government intrudes itself into every rank of society”’. The book was hailed as a masterpiece. ‘It is not only a work of brilliant social observation, but may be considered the first thriller and the first psychological novel which anticipates the anxieties of modern existentialism’ (1993: 196).

Around this time William Godwin met Mary Wollstonecraft and they became lovers. On falling pregnant, Wollstonecraft asked Godwin to marry her in (which he did in 1797 even though he was deeply critical of the institution – he believed that in this particular instance the ‘goods’ outweighed the ‘evils’. He seems to have been very happy during this period (living at 27 The Polygon in Somerstown) – but the moment was short. Wollstonecraft died in giving birth to Mary.

William Godwin continued to write – but intellectual and political tides were running against him. He married again in 1801 – Mary Jane Clairmont, a neighbour. Together they set up a Juvenile Library in Hanway Street (in 1805). They produced a series of pioneering children’s books – some by Godwin, many by other writers and published from the shop in Hanway Street. Later they were to move the business to Holborn – but they were continually beset by financial problems – and the debts rose. Money from writing was gradually drying up. In the end he had to accept a pension. Aged 77 he became Office Keeper and Yeoman Usher and was given lodgings in New Palace Yard (by the Houses of Parliament). As Marshall has noted: ‘It was the supreme irony of Godwin’s complicated life that he should end his days looking after an obsolete institution which he wished to see abolished’ (1993: 200). He died in 1836 and was buried, at his request, next to Mary Wollstonecraft.

Anarchism

According to Woodcock (1963: 57) William Godwin’s philosophy embraced all the essential features of an anarchist doctrine. He:

- Rejected any social system dependent on government.

- Put forward his own conception of a simplified and decentralized society with a dwindling minimum of authority, based on a voluntary sharing of material goods.

- Suggested his own means of proceeding towards it by means of a propaganda divorced from any kind of political party or political aim. (Woodcock 1963: 57)

Political Justice is a carefully reasoned argument that draws political conclusions from ethical presuppositions. He begins with an account of human nature that claims that the ‘moral characters of men are the result of their perceptions’ and that we are born neither good or bad. Man, William Goodwin suggests, is perfectable – capable of indefinite improvement. He looks to individuals. Society, he argued, exists to promote their welfare. His progressivism is primarily moral. It envisages ‘as its primary goal an inner change in the individual that will take him to the condition of natural justice from which his subjection to political institutions had diverted him’ (Woodcock 1963: 70). He believed that politics is not separable from ethics. However, as Marshall (1996: 219) has argued Godwin failed to develop an adequate praxis. While have a fundamental belief in reform, he was not clear on how it was to be achieved in the face of vested interest and state power.

He was left with the apparent dilemma of believing that human beings cannot become wholly rational as long as government exists, and yet government must continue to exist while they remain irrational. His problem was that he failed to tackle reform on the level of institutions. (op cit)

He did have a vision of sorts with regard to possible social arrangements. William Goodwin looked to the strengthening of local parishes and to a society based on the voluntary association of free and equal individuals. How this was to be achieved and in what it consists were not spelled out.

Education

Godwin placed education at the centre of his thinking – it was the main means by which change would be achieved.

The state of society is incontestably artificial; the power of one man over another must be always derived from convention of from conquest; by nature we are equal. The necessary consequence is, that government must always depend upon the opinion of the governed. Let the most oppressed people under heaven once change their mode of thinking, and they are free…. Government is very limited in its power of making men either virtuous or happy; it is only in the infancy of society that it can do any thing considerable; in its maturity it can only direct a few of our outward actions. But our moral dispositions and character depend very much, perhaps entirely, upon education. From An Account of a Seminary (1783) quoted by Woodcock (1963: 58)

The aim of education should be the promotion of happiness – and this necessarily involved the cultivation of wisdom and virtue. Smith (1983: 7 – 11) suggests three main features stand out:

- A respect for the child’s autonomy which precluded any form of coercion. William Goodwin argued that all are entitled to ‘an appropriate portion of independence’ – children and adults alike. He disliked the various ways in which adults coerced children – whether through harsh discipline and punishments or through the more general ‘unkindenesses’ of life. While Godwin drew much from Rousseau he parted company over the latter’s sleight of hand wherein teachers appear to be allowing children to do as they please but in reality are really in control – a disguised form of coercion (Smith 1983: 8).

- A pedagogy that respected this and sought to build on the child’s own motivation and initiatives. William Godwin recognized the significance of motivation and desire:

The most desirable mode of education… is that which is careful that all the acquisitions of the pupil shall be preceded and accompanied by desire… The boy, like the man, studies because he desires it. He proceeds upon a plan of is own invention, or by which, by adopting, he has made his own. Everything bespeaks independence and inequality. William Godwin (1797) The Enquirer (reprinted in Woodock 1977)

He argued that rather than the master going first and the pupil following, rather it is probable that ‘the pupil should go first and the master followed. Once this happens, the whole ‘formidable apparatus’ of education can be ‘swept away’. Unlike Rousseau he was not taken with individual tutoring – and saw the significance of learning as part of a group.

- A concern about the child’s capacity to resist an ideology transmitted through the school. Schools are powerful mechanisms of social control – and to hand this to the state is to subvert freedom. William Goodwin’s attack in Political Justice on ‘national education’, and the injuries associated with it, remains an indictment of state intervention and control. Inevitably he argues, national education will encourage the acceptance of existing social arrangements and institutions, subvert the development of a free consciousness, and seek to strengthen the state.

William Godwin’s educational thinking made some impact upon thinkers like Robert Owen – but it does not appear to have been a significant reference point for those seeking to develop more libertarian forms of education in the later part of the nineteenth century. However, he has left us with a powerful statement in support of non-curricula forms of education:

It is the characteristic of the mind to be capable of improvement. An individual surrenders the best attributes of man, the moment he resolves to adhere to certain fixed principles, for reasons not now present to his mind, but which formerly were. The instant in which he shuts upon himself the career of enquiry, is the instance of his intellectual decease…. No vice can be more destructive, than that which teaches us to regard any judgement as final, and not open to review. The same principle that applies to individuals, applies to communities. There is no proposition, at present apprehended to be true, so valuable, as to justify the introduction of an establishment for the purpose of inculcating it on mankind. Refer them to reading, to conversation, to meditation; but teach them neither creeds nor catechisms, either moral or political. William Goodwin ‘Of National Education’ in An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1971 edn: 237)

References

Godwin, William (1793) Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1971 edn. Edited by K. Codell Carter), London: Oxford University Press.

Marshall, P. (1984) William Godwin, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Marshall, P. (1993) Demanding the Impossible. A history of anarchism, London: Fontana.

Smith, M. P. (1983) The Libertarians and Education, London: Unwin Education Books.

Woodcock, G. (1963) Anarchism, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Websites

Start with The William Godwin Archive and go on from there. See also the video piece on William Godwin’s Juvenile Library

Acknowledgement: Picture: William Godwin by James Northcote (oil on canvas, 1802). National Portrait Gallery 1236 ccbyncnd2 licence.

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (1998, 2020) ‘William Goodwin and informal education’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [www.infed.org/thinkers/et-good.htm. Last update: insert date]

© Mark K. Smith 1998, 2020

updated: August 14, 2025