Refer them to reading, to conversation, to meditation; but teach them neither creeds nor catechisms, either moral or political.’ In this extract from Enquiry Concerning Political Justice William Godwin makes the case for the formative power of education.

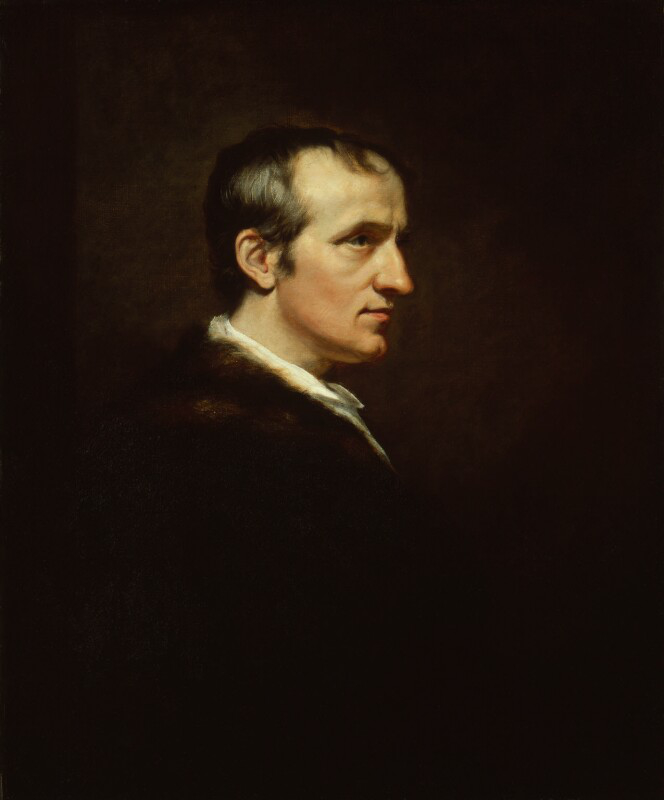

William Godwin (1756 – 1836) was the first writer ‘to give a clear statement of anarchist principles’ (Marshall 1993: 191). He was one of the first English-language writers to recognize the threat of state-controlled education and to set out the qualities of an alternative, free, education. Today he is perhaps best remembered as the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft (who wrote the feminist classic: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman -1792, the father of Mary Shelley (the author of Frankenstein – 1818) and the father-in-law of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (who was influenced by his radical libertarianism).

In this chapter (Chapter IV) from Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, William Godwin attacks those that argue that innate principles and theories that see human behaviour as being determined by instincts.

This version of the chapter is taken from the third, final revised edition of 1798 (see below). See, also, William Godwin and education.

__________________

Thus far we have argued from historical facts, and from them have collected a very strong presumptive evidence that political institutions have a more powerful and extensive influence than it has been generally the practice to ascribe to them.

But we can never arrive at precise conceptions relative to this part of the subject without entering into an analysis of the human mind, and endeavouring to ascertain the nature of the causes by which its operations are directed. Under this branch of the subject I shall attempt to prove two things: first, that the actions and dispositions of mankind are the offspring of circumstances and events, and not of any original determination that they bring into the world; and, secondly, that the great stream of our voluntary actions essentially depends, not upon the direct and immediate impulses of sense, but upon the decisions of the understanding. If these propositions can be sufficiently established, it will follow that the happiness men are able to attain is proportioned to the justness of the opinions they take as guides in the pursuit; and it will only remain, for the purpose of applying these premises to the point under consideration, that we should demonstrate the opinions of men to be, for the most part, under the absolute control of political institution.

First, the actions and dispositions of men are not the off-spring of any original bias that they bring into the world in favour of one sentiment or character rather than another, but flow entirely from the operation of circumstances and events acting upon a faculty of receiving sensible impressions.

There are three modes in which the human mind has been conceived to be modified, independently of the circumstances which occur to us, and the sensations excited: first, innate principles; secondly, instincts; thirdly, the original differences of our structure, together with the impressions we receive in the womb. Let us examine each of these in their order.

I. Innate principles

First, innate principles of judgement. Those by whom this doctrine has been maintained have supposed that there were certain branches of knowledge, and those perhaps of all others the most important, concerning which we felt an irresistible persuasion, at the same time that we were wholly unable to trace them through any channels of external evidence and methodical deduction. They conceived therefore that they were originally written in our hearts; or perhaps, more properly speaking, that there was a general propensity in the human mind suggesting them to our reflections, and fastening them upon our conviction. Accordingly, they established the universal consent of mankind as one of the most infallible criterions of fundamental truth. It appeared upon their system that we were furnished with a sort of sixth sense, the existence of which was not proved to us, like that of our other senses, by direct and proper evidence, but from the consideration of certain phenomena in the history of the human mind, which cannot be otherwise accounted for than by the assumption of this hypothesis.

There is an essential deficiency in every speculation of this sort. It turns entirely upon an appeal to our ignorance. Its language is as follows: “You cannot account for certain events from the known laws of the subjects to which they belong; therefore they are not deducible from those laws; therefore you must admit a new principle into the system for the express purpose of accounting for them.” But there cannot be a sounder maxim of reasoning than that which points out to us the error of admitting into our hypotheses unnecessary principles, or referring the phenomena that occur to remote and extraordinary sources, when they may with equal facility be referred to sources which obviously exist, and the results of which we daily observe. This maxim alone is sufficient to persuade us to reject the doctrine of innate principles. If we consider the infinitely various causes by which the human mind is perceptibly modified, and the different principles, argument, imitation, inclination, early prejudice and imaginary interest, by which opinion is generated, we shall readily perceive that nothing can be more difficult than to assign any opinion, existing among the human species, and at the same time incapable of being generated by any of these causes and principles.

A careful enquirer will be strongly inclined to suspect the soundness of opinions which rest for their support on so ambiguous a foundation as that of innate impression. We cannot reasonably question the existence of facts; that is, we cannot deny the existence of our sensations, or the series in which they occur. We cannot deny the axioms of mathematics; for they exhibit nothing more than a consistent use of words, and affirm of some idea that it is itself and not something else. We can entertain little doubt of the validity of mathematical demonstrations, which appear to be irresistible conclusions deduced from identical propositions. We ascribe a certain value, sometimes greater and sometimes less, to considerations drawn from analogy. But what degree of weight shall we attribute to affirmations which pretend to rest upon none of these grounds? The most preposterous propositions, incapable of any rational defence, have in different ages and countries appealed to this inexplicable authority, and passed for infallible and innate. The enquirer that has no other object than truth, that refuses to be misled, and is determined to proceed only upon just and sufficient evidence will find little reason to be satisfied with dogmas which rest upon no other foundation than a pretended necessity impelling the human mind to yield its assent.

But there is a still more irresistible argument proving to us the absurdity of the supposition of innate principles. Every principle is a proposition: either it affirms, or it denies. Every proposition consists in the connection of at least two distinct ideas, which are affirmed to agree or disagree with each other. It is impossible that the proposition can be innate, unless the ideas to which it relates be also innate. A connection where there is nothing to be connected, a proposition where there is neither subject nor conclusion, is the most incoherent of all suppositions. But nothing can be more incontrovertible than that we do not bring pre-established ideas into the world with us.

Let the innate principle be that “virtue is a rule to which we are obliged to conform.” Here are three principal and leading ideas, not to mention subordinate ones, which it is necessary to form, before we can so much as understand the proposition. What is virtue? Previously to our forming an idea corresponding to this general term, it seems necessary that we should have observed the several features by which virtue is distinguished, and the several subordinate articles of right conduct, that taken together constitute that mass of practical judgements to which we give the denomination of virtue. These are so far from being innate that the most impartial and laborious enquirers are not yet agreed respecting them. The next idea included in the above proposition is that of a rule or standard, a general measure with which individuals are to be compared, and their conformity or disagreement with which is to determine their value. Lastly, there is the idea of obligation, its nature and source, the obliger and the sanction, the penalty and the reward.

Who is there in the present state of scientifical improvement that will believe that this vast chain of perceptions and notions is something that we bring into the world with us, a mystical magazine, shut up in the human embryo, whose treasures are to be gradually unfolded as circumstances shall require? Who does not perceive that they are regularly generated in the mind by a series of impressions, and digested and arranged by association and reflection?

II. Instincts

But, if we are not endowed with innate principles of judgement, it has nevertheless been supposed by some persons that we might have instincts to action, leading us to the performance of certain useful and necessary functions, independently of any previous reasoning as to the advantage of these functions. These instincts, like the innate principles of judgement we have already examined, are conceived to be original, a separate endowment annexed to our being, and not anything that irresistibly flows from the mere faculty of perception and thought, as acted upon by the circumstances, either of our animal frame, or of the external objects, by which we are affected. They are liable therefore to the same objection as that already urged against innate principles. The system by which they are attempted to be established is a mere appeal to our ignorance, assuming that we are fully acquainted with all the possible operations of known powers, and imposing upon us an unknown power as indispensable to the accounting for certain phenomena. If we were wholly unable to solve these phenomena, it would yet behove us to be extremely cautious in affirming that known principles and causes are inadequate to their solution. If we are able upon strict and mature investigation to trace the greater part of them to their source, this necessarily adds force to the caution here recommended.

An unknown cause is exceptionable, in the first place, inasmuch as to multiply causes is contrary to the experienced operation of scientifical improvement. It is exceptionable, secondly, because its tendency is to break that train of antecedents and consequents of which the history of the universe is composed. It introduces an action apparently extraneous, instead of imputing the nature of what follows to the properties of that which preceded. It bars the progress of enquiry by introducing that which is occult, mysterious and incapable of further investigation. It allows nothing to the future advancement of human knowledge; but represents the limits of what is already known, as the limits of human understanding.

Let us review a few of the most common examples adduced in favour of human instincts, and examine how far they authorize the conclusion that is attempted to be drawn from them: and first, some of those actions which appear to rise in the most instantaneous and irresistible manner.

A certain irritation of the palm of the hand will produce that contraction of the fingers which accompanies the action of grasping. This contraction will at first take place unaccompanied with design, the object will be grasped without any intention to retain it, and let go again without thought or observation. After a certain number of repetitions, the nature of the action will be perceived; it will be performed with a consciousness of its tendency; and even the hand stretched out upon the approach of any object that is desired. Present to the child, thus far instructed, a lighted candle. The sight of it will produce a pleasurable state of the organs of perception. He will probably stretch out his hand to the flame, and will have no apprehension of the pain of burning till he has felt the sensation.

At the age of maturity, the eyelids instantaneously close when any substance from which danger is apprehended is advanced towards them; and this action is so constant as to be with great difficulty prevented by a grown person, though he should explicitly desire it. In infants there is no such propensity; and an object may be approached to their organs, however near and however suddenly, without producing this effect. Frowns will be totally indifferent to a child, who has never found them associated with the effects of anger. Fear itself is a species of foresight, and in no case exists till introduced by experience.

It has been said that the desire of self-preservation is innate. I demand what is meant by this desire? Must we not understand by it a preference of existence to nonexistence? Do we prefer anything but because it is apprehended to be good ? It follows that we cannot prefer existence, previously to our experience of the motives for preference it possesses. Indeed the ideas of life and death are exceedingly complicated, and very tardy in their formation. A child desires pleasure and loathes pain long before he can have any imagination respecting the ceasing to exist.

Again, it has been said that self-love is innate. But there cannot be an error more easy of detection. By the love of self we understand the approbation of pleasure, and dislike of pain: but this is only the faculty of perception under another name. Who ever denied that man was a percipient being? Who ever dreamed that there was a particular instinct necessary to render him percipient?

Pity has sometimes been supposed an instance of innate principle; particularly as it seems to arise with greater facility in young persons, and persons of little refinement, than in others. But it was reasonable to expect that threats and anger, circumstances that have been associated with our own sufferings, should excite painful feelings in us in the case of others, independently of any laboured analysis. The cries of distress, the appearance of agony or corporal infliction, irresistibly revive the memory of the pains accompanied by those symptoms in ourselves. Longer experience and observation enable us to separate the calamities of others and our own safety, the existence of pain in one subject and of pleasure or benefit in others, or in the same at a future period, more accurately than we could be expected to do previously to that experience.

III. Effects of antenatal impressions and original structure

If then it appear that the human mind is unattended either with innate principles or instincts, there are only two remaining circumstances that can be imagined to anticipate the effects of institution, and fix the human character independently of every species of education: these are, the qualities that may be produced in the human mind previously to the era of our birth, and the differences that may result from the different structure of the greater or subtler elements of the animal frame.

To objections derived from these sources the answer will be in both cases similar.

First, ideas are to the mind nearly what atoms are to the body. The whole mass is in a perpetual flux; nothing is stable and permanent; after the lapse of a given period not a single particle probably remains the same. Who knows not that in the course of a human life the character of the individual frequently undergoes two or three revolutions of its fundamental stamina? The turbulent man will frequently become contemplative, the generous be changed into selfish, and the frank and good-humoured into peevish and morose. How often does it happen that, if we meet our best loved friend after an absence of twenty years, we look in vain in the man before us for the qualities that formerly excited our sympathy, and, instead of the exquisite delight we promised ourselves, reap nothing but disappointment? If it is thus in habits apparently the most rooted, who will be disposed to lay any extraordinary stress upon the impressions which an infant may have received in the womb of his mother?

He that considers human life with an attentive eye will not fail to remark that there is scarcely such a thing in character and principles as an irremediable error. Persons of narrow and limited views may upon many occasions incline to sit down in despair; but those who are inspired with a genuine energy will derive new incentives from miscarriage. Has any unfortunate and undesirable impression been made upon the youthful mind? Nothing will be more easy than for a judicious superintendent, provided its nature is understood, and it is undertaken sufficiently early, to remedy and obliterate it. Has a child passed a certain period of existence in ill-judged indulgence and habits of command and caprice? The skilful parent, when the child returns to its paternal roof, knows that this evil is not invincible, and sets himself with an undoubting spirit to the removal of the depravity. It often happens that the very impression which, if not counteracted, shall decide upon the pursuits and fortune of an entire life might perhaps under other circumstances be reduced to complete inefficiency in half an hour.

It is in corporeal structure as in intellectual impressions. The first impressions of our infancy are so much upon the surface that their effects scarcely survive the period of the impression itself. The mature man seldom retains the faintest recollection of the incidents of the two first years of his life. Is it to be supposed that that which has left no trace upon the memory can be in an eminent degree powerful in its associated effects? Just so in the structure of the animal frame. What is born into the world is an unfinished sketch, without character or decisive feature impressed upon it. In the sequel there is a correspondence between the physiognomy and the intellectual and moral qualities of the mind. But is it not reasonable to suppose that this is produced by the continual tendency of the mind to modify its material engine in a particular way? There is for the most part no essential difference between the child of the lord and of the porter. Provided he do not come into the world infected with any ruinous distemper, the child of the lord, if changed in the cradle, would scarcely find any greater difficulty than the other in learning the trade of his softer father, and becoming a carrier of burthens. The muscles of those limbs which are most frequently called into play are always observed to acquire peculiar flexibility or strength. It is not improbable, if it should be found that the capacity of the skull of a wise man is greater than that of a fool, that this enlargement should be produced by the incessantly repeated action of the intellectual faculties, especially if we recollect of how flexible materials the skulls of infants are composed, and at how early an age persons of eminent intellectual merit acquire some portion of their future characteristics.

In the meantime it would be ridiculous to question the real differences that exist between children at the period of their birth. Hercules and his brother, the robust infant whom scarcely any neglect can destroy, and the infant that is with difficulty reared, are undoubtedly from the moment of parturition very different beings. If each of them could receive an education precisely equal and eminently wise, the child labouring under original disadvantage would be benefited, but the child to whom circumstances had been most favourable in the outset would always retain his priority. These considerations however do not appear materially to affect the doctrine of the present chapter; and that for the following reasons.

First, education never can be equal. The inequality of external circumstances in two beings whose situations most nearly resemble is so great as to baffle all power of calculation. In the present state of mankind this is eminently the case. There is no fact more palpable than that children of all sizes and forms indifferently become wise. It is not the man of great stature or vigorous make that outstrips his fellow in understanding. It is not the man who possesses all the external senses in the highest perfection. It is not the man whose health is most vigorous and invariable. Those moral causes that awaken the mind, that inspire sensibility, imagination and perseverance, are distributed without distinction to the tall or the dwarfish, the graceful or the deformed, the lynx-eyed or the blind. But, if the more obvious distinctions of animal structure appear to have little share in deciding upon their associated varieties of intellect, it is surely in the highest degree unjustifiable to attribute these varieties to such subtle and imperceptible differences as, being out of our power to assign, are yet gratuitously assumed to account for the most stupendous effects. This mysterious solution is the refuge of indolence or the instrument of imposture, but incompatible with a sober and persevering spirit of investigation.

Secondly, it is sufficient to recollect the nature of moral causes to be satisfied that their efficiency is nearly unlimited. The essential differences that are to be found between individual and individual originate in the opinions they form, and the circumstances by which they are controlled. It is impossible to believe that the same moral train would not make nearly the same man. Let us suppose a being to have heard all the arguments and been subject to all the excitements that were ever addressed to any celebrated character. The same arguments, with all their strength and all their weakness, unaccompanied with the smallest addition or variation, and retailed in exactly the same proportions from month to month and year to year, must surely have produced the same opinions. The same excitements, without reservation, whether direct or accidental, must have fixed the same propensities. Whatever science or pursuit was selected by this celebrated character must be loved by the person respecting whom we are supposing this identity of impressions. In fine, it is impression that makes the man, and, compared with the empire of impression, the mere differences of animal structure are inexpressibly unimportant and powerless.

These truths will be brought to our minds with much additional evidence if we compare in this respect the case of brutes with that of men. Among the inferior animals, breed is a circumstance of considerable importance, and a judicious mixture and preservation in this point is found to be attended with the most unequivocal results. But nothing of that kind appears to take place in our own species. A generous blood, a gallant and fearless spirit is by no means propagated from father to son. When a particular appellation is granted, as is usually practised in the existing governments of Europe, to designate the descendants of a magnanimous ancestry, we do not find, even with all the arts of modern education, to assist, that such descendants are the legitimate representatives of departed heroism. Whence comes this difference? Probably from the more irresistible operation of moral causes. It is not impossible that among savages those differences would be conspicuous which with us are annihilated. It is not unlikely that if men, like brutes, were withheld from the more considerable means of intellectual improvement, if they derived nothing from the discoveries and sagacity of their ancestors, if each individual had to begin absolutely de novo in the discipline and arrangement of his ideas, blood or whatever other circumstances distinguish one man from another at the period of his nativity would produce as memorable effects in man as they now do in those classes of animals that are deprived of our advantages. Even in the case of brutes, education and care on the part of the man seem to be nearly indispensable, if we would not have the foal of the finest racer degenerate to the level of the cart-horse. In plants the peculiarities of soil decide in a great degree upon the future properties of each. But who would think of forming the character of a human being by the operations of heat and cold, dryness and moisture upon the animal frame? With us moral considerations swallow up the effects of every other accident. Present a pursuit to the mind, convey to it the apprehension of calamity or advantage, excite it by motives of aversion or motives of affection, and the slow and silent influence of material causes perishes like dews at the rising of the sun.

The result of these considerations is that at the moment of birth man has really a certain character, and each man a character different from his fellows. The accidents which pass during the months of percipiency in the womb of the mother produce a real effect. Various external accidents, unlimited as to the period of their commencement, modify in different ways the elements of the animal frame. Everything in the universe is linked and united together. No event, however minute and imperceptible, is barren of a train of consequences, however comparatively evanescent those consequences may in some instances be found. If there have been philosophers that have asserted otherwise, and taught that all minds from the period of birth were precisely alike, they have reflected discredit by such an incautious statement upon the truth they proposed to defend.

But, though the original differences of man and man be arithmetically speaking something, speaking in the way of a general and comprehensive estimate they may be said to be almost nothing. If the early impressions of our childhood may by a skilful observer be as it were obliterated almost as soon as made, how much less can the confused and unpronounced impressions of the womb be expected to resist the multiplicity of ideas that successively contribute to wear out their traces? If the temper of the man appear in many instances to be totally changed, how can it be supposed that there is anything permanent and inflexible in the propensities of a new-born infant? and, if not in the character of the disposition, how much less in that of the understanding?

Speak the language of truth and reason to your child, and be under no apprehension for the result. Show him that what you recommend is valuable and desirable, and fear not but he will desire it. Convince his understanding, and you enlist all his powers animal and intellectual in your service. How long has the genius of education been disheartened and unnerved by the pretence that man is born all that it is possible for him to become? How long has the jargon imposed upon the world which would persuade us that in instructing a man you do not add to, but unfold his stores? The miscarriages of education do not proceed from the boundedness of its powers, but from the mistakes with which it is accompanied. We often inspire disgust, where we mean to infuse desire. We are wrapped up in ourselves, and do not observe, as we ought, step by step the sensations that pass in the mind of our hearer. We mistake compulsion for persuasion, and delude ourselves into the belief that despotism is the road to the heart.

Education will proceed with a firm step and with genuine lustre when those who conduct it shall know what a vast field it embraces; when they shall be aware that the effect, the question whether the pupil shall be a man of perseverance and enterprise or a stupid and inanimate dolt, depends upon the powers of those under whose direction he is placed and the skill with which those powers shall be applied. Industry will be exerted with tenfold alacrity when it shall be generally confessed that there are no obstacles to our improvement which do not yield to the powers of industry. Multitudes will never exert the energy necessary to extraordinary success, till they shall dismiss the prejudices that fetter them, get rid of the chilling system of occult and inexplicable causes, and consider the human mind as an intelligent agent, guided by motives and prospects presented to the understanding, and not by causes of which we have no proper cognisance and can form no calculation.

Acknowledgements: in by James Northcote (oil on canvas, 1802). National Portrait Gallery 1236 ccbyncnd2 licence

How to cite this piece: Godwin, William (1798). Book 1, Chapter 4 ‘The Characters of Man Originate in their External Circumstances’ in Enquiry concerning political justice and its influence on morals and happiness Volume 1 [final revised edition]. London: Robinson. Reproduced in the informal education archives [www.infed.org/e-texts/william_godwin_political_justice_chapter4.htm. Retrieved: insert date].

This piece has been reproduced here on the understanding that it is not subject to any copyright restrictions, and that it is, and will remain, in the public domain.

First placed in the archives: September 2009.