Picture: George Williams (1821-1905), founder of the YMCA – by John Collier. National Portrait Gallery | ccby4

Tony Jeffs reflects on the YMCA’s 135-year engagement across the world with the professional education of those working with young people. He examines both the innovations and tensions involved in the growth and experience of different programmes, and the factors that led to the decline of informal and youth work education within the YMCA. This important research is also available to download as a pdf.

——

contents: introduction | background | commencement | humanics | Chicago – beginnings | Nashville | overseas | drifting apart – Springfield | Chicago – victim of circumstance | London | farewell | bibliography

Introduction

YMCA George Williams College (London) looked like closing at the end of 2020. Final year degree programmes, for the tiny residue of students yet to graduate, were taught out through Coventry University, whilst the further education department simply closed. Come 2021 all that remained was to tie up the administrative loose ends. Bizarrely the extant web page still proclaimed the College to be “the leading provider of Youth and Community training and qualifications across the UK”. This vainglorious boast underscores how precipitously thriving institutions can be brought to their knees. Sadly, the likely loss of an institution which made a valuable contribution to youth and community work education in Britain went unacknowledged. Equally, no recognition was forthcoming that its disappearance signified the end of the YMCA’s 135-year engagement with the professional education of youth workers. Subsequently, in 2022, the residue of the College merged with the Centre for Youth Impact. The focus of the new entity is on outcomes, ‘good data’ and ‘quality practice’. This marked a fundamental shift in emphasis away from the College’s concern with the ever-changing experiences of relationships, processes, and growth within community learning and development, and youth work. It confirmed that teaching a new generation of practitioners has ceased to be a priority and the cessation of undergraduate and post-graduate level education. It thereby signified the dénouement of an honourable chapter.

Background

George Williams hosted the initial meeting in June 1844 that preceded the formation of the YMCA. Six years later, after it had become a flourishing movement in Great Britain, the YMCA crossed the Atlantic. America proved fertile ground. Within a decade, the total membership there stood just short of double that of Great Britain’s (Doggett, 1916: 172). Moreover, according to Doggett, who wrote the first history of the worldwide YMCA, the Associations in North America from the outset acquired a discrete persona. Overall, they were ‘larger in membership, more aggressive, less spiritual, with a greater variety of activities’ (ibid.: 171). Initially, these operated out of shop fronts, church halls and private homes. As membership grew, Associations aspired towards owning their own buildings. Chicago, which opened its three-storey Farwell Hall in 1867, was probably the first to achieve this ambition (Dedmon, 1957; Lupkin, 2010).

Primarily designed in line with guidance furnished by its foremost member, the evangelist Dwight Moody, it was dominated by an auditorium capable of seating over 3,500 people. In addition, there were some large prayer rooms, and offices for staff and sympathetic religious organisations, plus a frontage of shops which furnished a rental income. Farwell Hall fulfilled the expectations of its founders by becoming ‘the scene of a constant round of religious meetings, all carried on with revivalistic fervour’ (Dunn, 1944: 349). Both the YMCA and its building consciously played a pivotal role in launching or sustaining in the city the ‘cause of temperance, and for the suppression of obscene literature, against “Sabbath desecration”, smoking, theatergoing, dancing and billiards (ibid.: 350).

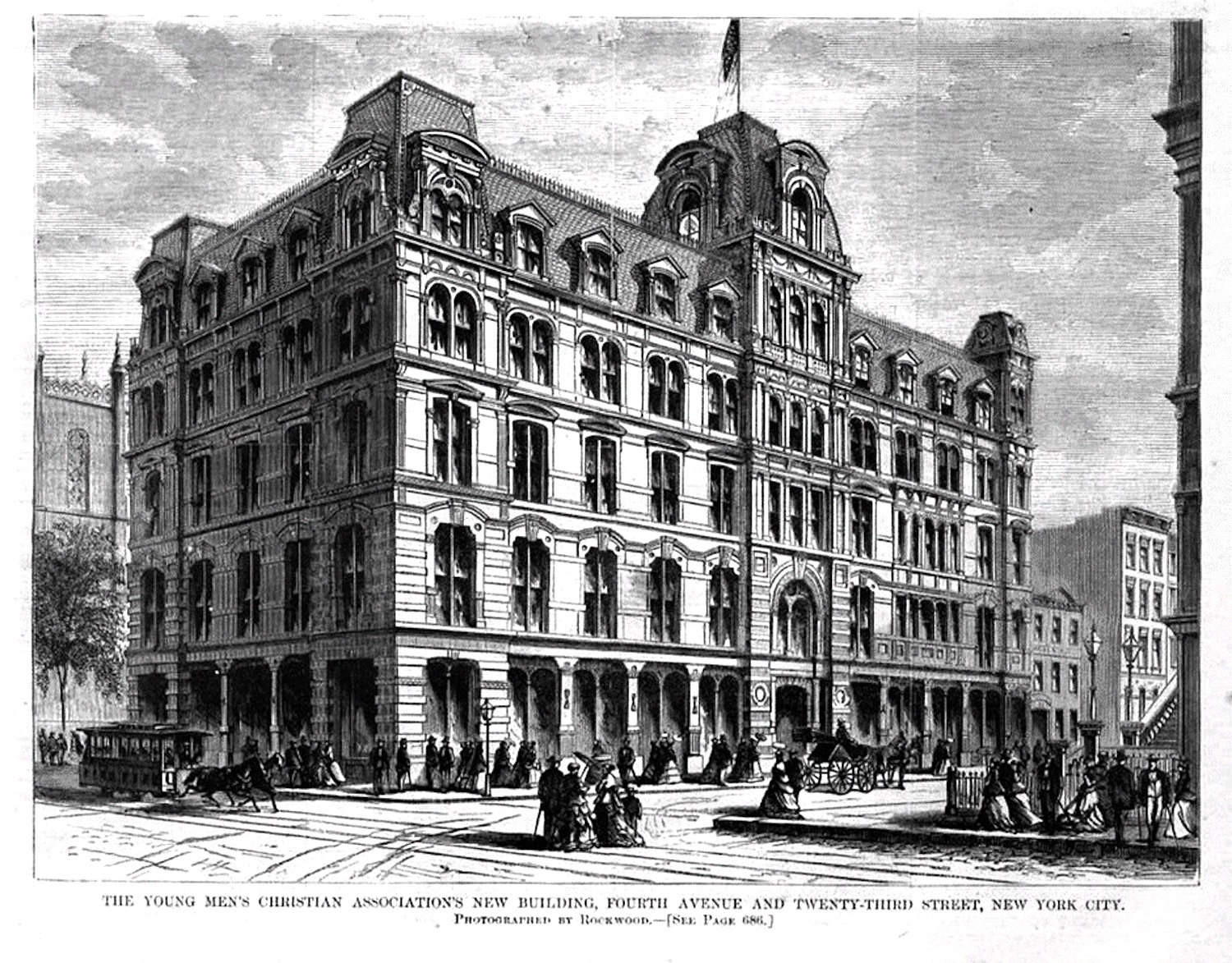

Given its function as a revivalist centre, it made sense for Chicago, unlike most Associations, to welcome women into membership (Lupkin, 2010: 78). Over time this policy attracted mounting criticism within the Movement. Primarily orchestrated by Robert McBurney, Secretary of the New York YMCA, this disapproval eventually culminated in the passing of a National Convention resolution stating that the YMCA’s ‘chief object is to reach young men’. This effectively mandated Chicago to forthwith exclude women from membership (Dedmon, 1957: 81). Farwell Hall burned down in 1869. One year later, a smaller replacement was operating, but this in turn was destroyed in the 1871 Great Fire of Chicago. Within three years, a third, constructed on the original site, was up and running. Although they led the charge, the designs of these three Chicago buildings were outliers. Few Associations replicated them. Indeed in 1893, Chicago fell into line with what had become the dominant template when it constructed a new thirteen-storey headquarters which eclipsed the New York model it emulated.

Two years after the original Farwell Hall opened, New York’s 23rd Street YMCA was completed. It was adopted as the blueprint for all but a few of the thousand or so YMCA buildings constructed during the ‘Building Movement’. This ran from the mid-1870s through to the onset of the First World War (Lupkin, 2010). Five storeys and costing the equivalent of $15,000,000 (in 2021), 23rd Street “Y” incorporated: residential accommodation for 400 members, a ‘Grand Hall’ seating 1,500, a large gymnasium, bowling alley, reading rooms, a 20,000-volume library, baths, parlours, canteens and restaurants. It also had teaching and lecture rooms, an art gallery, artist studios, a penthouse apartment for the General Secretary and a flat for the janitor and their family. Crucially, it also had discrete premises for a 200-member club for boys aged 14 to 17, and a frontage comprising retail units to provide rental income.

No vanity project, this edifice was painstakingly designed to dispense the ‘fourfold model’ of practice devised by Robert McBurney. It was formulated to enhance members’ ‘spiritual, mental, social and physical’ well-being. This building would, according to McBurney, personify the essence of what the YMCA was created to achieve:

The idea that if a building could be erected answering to a club house for young men, with everything in it calculated to exert a cheering and brotherly influence, where they could grasp a friendly hand when they came in, and where gymnasiums and music and classes for study were to be found as well as religious and Bible meetings, an influence would thus be exerted upon these young men that would hold and gradually mould them until their habits were fixed in the right direction. (1899: 1)

North America in 1866 had just three full-time secretaries. Come 1873 the total was 53, by 1881 it was 210 and four years later it exceeded 400 (Bowne, 1885: 5). Only six Associations operated from purpose-built premises in 1869 (Morse, 1918: 79). When McBurney died in 1898 New York alone had 15 purpose-built branches employing 149 full-time staff. At the close of four decades of expansion, over 3,600 general and assistant secretaries were in post (Morse, 1913: 156). Scarcely a town or city of note by then lacked a main street YMCA – a ‘Christian Clubhouse’ or what President Theodore Roosevelt dubbed a ‘factory of manhood’ (quoted Lupkin, 2010: xvi). Inevitably, these buildings re-aligned the Movement’s ethos, transforming it, as a sympathetic historian remarked, ‘into a business concern’ wherein ‘the executive function came to the fore’ (Hopkins, 1951: 162).

Most required a platoon of paid workers and a regiment of volunteers to keep them ticking over. Notably, this included a general secretary to oversee the building, manage the ‘fourfold’ programme and supervise the specialist staff who often included:

- instructors competent to coach and administer the gymnastic and sports programmes and facilities;

- educationalists to organise and teach classes;

- librarians;

- leaders to manage the boys’ club;

- caterers, housekeepers and janitors to superintend the restaurant, accommodation and building; and

- pastors to undertake evangelical work within and without the premises.

In addition, the YMCA, locally and nationally, was dependent upon a legion of men capable of developing the hundreds of college-based branches; managing the network of buildings catering for railway workers; functioning as travelling secretaries initiating new and sustaining existing Associations; and undertaking missionary and Secretarial work overseas.

Expectations that senior members, college graduates, qualified professionals and businessmen would transition to fill these vacancies had, by 1880, proved erroneous. Moreover, staff turnover remained alarmingly high. During the 1870s, for example, approximately a fifth of all general secretaries left the organisation annually (Hopkins, 1951: 172). Jacob Bowne, Secretary to the YMCA International Committee during the early 1880s, undertook research into this staff turnover. He discovered that in a twenty-month period prior to the end of 1884, forty per cent of the 649 who joined the workforce in that timespan departed it within little over a year (Bowne, 1885). Bowne was now convinced that only entry subsequent to a period of full-time professional training would curtail this excessive rate of turnover. The initial remedy, however, was a ‘training by contact’ or ‘apprenticeship’ initiative centrally managed by Bowne. Recruits spent a year learning alongside experienced secretaries and via attendance at summer camps and conventions. Sixty-four men completed the ‘apprenticeship’ between 1881 and 1882, of these 52 entered YMCA employment (Morse, 1913: 157). Bowne and others who shared his viewpoint held that the ‘apprenticeship’ model was at best an interim solution. They pressed for the formation of dedicated YMCA training schools. Eventually, their pressure paid off and the first opened in Springfield (Massachusetts) in 1885, trailed by a second in Chicago five years later.

Bowne proved to be correct in his analysis. At the turn of the century James McCurdy, who taught at the School for Christian Workers (Springfield) with a short break from 1895 to 1926, and whose son subsequently served as President of George Williams College (Chicago) from 1953 to 1961, undertook a study as to the comparative length of service undertaken by secretaries. This found that those who trained at Springfield or Chicago stayed in post three times longer than colleagues recruited from business or after completing a ‘mainstream’ degree at another college (Doggett, 1943: 124). This finding was subsequently confirmed by research undertaken by the International Committee of the American YMCA. It showed that between 1902 and 1907, a total of 2,175 entered the employee of the Movement as officers; of these, 1,517 left, and amongst the remainder, there were 1,720 changes of position. Notably, just a fifth of ‘training school’ graduates departed compared with 70 per cent of those from other backgrounds (The Training School Bulletin December 1908: 1). The evidence appeared incontrovertible – a sustainable future for the YMCA would in part rely upon the creation of a graduate-level training programme.

The campaign to establish training schools had begun in earnest at the 1872 Lovell YMCA National Conference. Robert Weidensall urged delegates to accept that these would be the surest route to creating a cadre of professional secretaries willing to embrace YMCA work as a life-long ‘calling’ (Doggett, 1943: 27). Initially, this proposal attracted widespread disapproval amongst members. Opponents feared that a professional secretariat would commandeer the Movement and wrest control away from the lay membership. This perceived threat was usually labelled ‘secretarialism’ (Morse, 1918: 80-81). Qualms regarding ‘professionalisation’ faded when the acute shortage of suitable candidates for secretarial posts threatened to curtail further expansion. However, they never fully evaporated. The statistics spoke loud and clear. Between 1880 and 1885 the number of employed officers tripled and then tripled again during the following seven years (Gustav-Wrathall, 1998: 81). In 1892 there were over 1,100 full-time staff in post, but worryingly nearly one in seven posts remained unfilled (Ninde, Bowne and Uhl, 1892: 55). By the onset of the 1880s a clear majority within the Movement’s leadership were, to varying degrees, disposed to lend moral, if not financial, assistance to bringing about the formation of one or more YMCA training schools to address this issue (Morse, 1918: 188).

Commencement

Professional youth work education originated in Springfield, Massachusetts. David Allen Reed, a Congregational Minister based in the town, resolved to open a School for Christian Workers to train a future workforce. He had been unable to recruit sufficient men and women to undertake parish and Sunday School work – the latter having a weekly attendance exceeding 800. Reed, long an active supporter of the YMCA, from the outset, envisaged that the School would train men to serve as Association secretaries. Hence, amongst those he invited to help plan this venture was Robert McBurney, who remained a Trustee until his death in 1898. Such was McBurney’s commitment to the College that he left it a quarter of his not insubstantial estate (Doggett, 1902: 248). Reed quickly secured funding to construct a three-storey building complete with a gymnasium, 16 lecture and meeting rooms, and residential accommodation for more than 20 students. The development was designed to furnish a home for both the School for Christian Workers and the newly formed Armory Hill YMCA. It is an indication of the pivotal role played by the YMCA in many American communities during this time that when Armory Hill opened, Springfield, a town with 44,000 inhabitants, already possessed three active YMCA branches. One, established in 1855, was the third oldest in the United States (Doggett, 1916: 128).

The School for Christian Workers opened on January 1, 1885, with five students enrolled on the year-long course. Twenty-three freshmen attended at the outset of the next academic year (Bowne, 1885: 15). By September 1888, 58 (including 11 from overseas) were studying on the newly extended two-year programme; plus four on a one-year post-graduate route (Garvey and Ziemba, 2010). Irrespective of the grave shortfall in the number of suitable general secretaries, a policy of accepting ‘all-comers’ was vetoed. All applicants, besides having to submit a letter of recommendation from an approved Christian Minister, had first to successfully complete a written academic examination; second, pass a demanding gymnasium test designed to weed out the physically unfit; and third, pass a swimming and diving test conducted in the nearby lake. Despite these obstacles, the competition for places was such that only one in six applicants secured admittance. During the first decade, a significant proportion of the intake applied after completing a degree or study programme elsewhere. For example, during 1891, 46 per cent of those completing the Secretarial course and 20 per cent of those finishing the Physical Education programme were graduates of other colleges and universities. To accommodate this, students could carry forward ‘credits’ based on relevant prior learning. Partly as a consequence of this flexibility, the average age of entry was 23; and the majority of students prior to 1892 finished the two-year programme in a single year.

Initially, the School comprised two ‘Training Schools’. One for “Sunday School Workers and Pastors’ Helpers”; and another for “YMCA Secretaries”. Of the pair, the latter was always a far more popular option, usually by a ratio of four or five to one. Jacob Bowne accepted the invitation to be the Head of the YMCA Secretaries Training School in 1885. During the 35 years that followed, he served variously as President of the College, Head of Department, lecturer and librarian. Bowne’s career trajectory – high school, business, and then General Secretary of Newburgh (New York State) YMCA was followed by a series of senior administrative roles within the Movement. He attended neither a college nor a university. Almost certainly this mattered little, for he was an authentic autodidact, an organic intellectual with a ‘scientific reverence for facts’ (Burr, 1932: 12). Bowne instinctively adjusted to college life, research, and teaching. An intuitive scholar, it was his painstakingly accrued collection of YMCA publications and internal documentation gathered over a lifetime which was to serve as ‘the basis for the University of Minnesota YMCA archive’ (Katz, 2001: 33).

Besides amassing the earliest youth work archive, Bowne was principally responsible for the production of the first youth work textbook.

Bowne was in so many ways a faultless appointment for a new institution striving to clarify its role and identity. For a start, his distinguished YMCA career and high standing deflected much potential criticism within the Movement. His intellectual gifts meant he grasped, from the outset, that if Springfield was to prosper it must mature into something more than a narrowly specialist training school. William Ballantine, a long-serving colleague, wrote an obituary which captures in part Bowne’s singular talents and distinctive contribution:

It seems a matter of course now that Association officers should have a professional education. It did not seem so to many Association leaders forty years ago. One remarkable thing is that although Mr. Bowne was not himself a college graduate he always had the university point of view. He saw, what so many religious workers fail to see even today, that intellectual and spiritual life should go on together, each contributing to the other. How intellectual a man he was appears from the fact that in a life of long hours devoted to the details of service he found time to study the antiquities of the American Indian and to collect stone implements. In this, which was to him recreation, he became an explorer and an authority.

This breadth of intellectual life saved Mr Bowne from the narrow theological dogmatism which was characteristic of most early Association leaders. He was a warm personal admirer and trusted friend of all these leaders. It gave him pain to differ with them, but he could not share their narrowness. This quality was absolutely vital as the College grew and was constantly attacked by good and sincere, but narrow-minded Association secretaries because here students were encouraged to think for themselves and to read the works of scientific thinkers. (1925: 12)

Bowne, Reed and five local clergymen initially undertook the bulk of the teaching aided by six visiting lecturers, amongst whom were two celebrated evangelists who had held senior positions within the YMCA – Dwight Moody and S. M. Sayford. In addition to courses delivered by the specialist schools they were attached to every student had to successfully complete a mandatory “General Course”. Spread over two years this comprised: Bible History and Exegesis; The History of Evangelical Christianity; Christian Evidences; Old and New Testament Canon; Fundamental Doctrines of the Bible; Books of the Bible; Christian Ethics; Outline Study of Man; Practical Methods of Christian Work; Rules for Deliberative Bodies; Rhetoric and Logic; and Vocal Music.

Besides the academic demands placed upon them, students were required to comply with an almost monastic “Approved Division of Time”:

______________________________________________________

Approved Division of Time:

6.00 am Rising Bell

6.15 to 7.00 Private devotion and preparation for the day’s work

7.00 to 7.30 Breakfast

7.30 to 8.00 Walking in the open air

8.00 to 8.15 Put room in order

8.15 to 11.00 Study

11.00 to 12.00 Recitations

12.00 to 12.45 Instruction in gymnasium

1.00 to 1.30 pm Dinner

1.30 to 3.00 Study

3.00 to 5.00 Recitation

5.00 to 5.15 Evening prayer

5.15 to 6.00 Walking in open air or instruction in gymnasium

6.00 to 6.30 Supper

6.30 to 7.00 Rest

7.00 to 9.30 Study, reading and practical Christian work

10.30 Building closes and lights out.

Suggestions:

- Get eight full hours sleep;

- Saturday should be devoted to recreation;

- Avoid more than four engagements on the Sabbath;

- In all things observe I Corinthians x:13 [There hath no temptation taken you but such is common to man: but God is faithful, who will not suffer you to be tempted above that ye are able, but will with the temptation also make a way to escape, that ye may be able to bear it.] (The King James Version of the Bible).

______________________________________________________

The recitations referred to in the “Division of Time” were what contemporary students would deem a mix of lecture and seminar for which papers might be prepared and pre-reading undertaken. Each and every recitation commenced with a prayer. On Sunday students were required to attend an approved church of their choice and ‘take part in church work’. The academic year comprised 40 weeks; in addition, those training to be a general secretary had to attend a minimum of two off-campus YMCA conventions (conferences) annually. By contemporary standards this amounted to a punishing academic regime.

In 1887 the School transferred to a lakeside location a mile or so distant from the Armory Hill YMCA. The first new building to be completed was a gymnasium, soon classrooms, a library, playing fields and dormitories followed. The expense entailed in creating a functioning campus meant that despite the best efforts of those who undertook the task of fund-raising, staff during these early years received ‘low salaries … often in arrears’ (Burr, 1932: 14). Acquisition of gymnasia to which students had exclusive access allowed for the formation of a new “Physical Department for the Training of YMCA Physical Directors”.

Luther Gulick arrived in September 1887 to take charge of this assisted by Robert J. Roberts. Roberts as the Physical Education Director of Boston YMCA had pioneered the use of gymnasiums within the YMCA. He also, incidentally, conjured up the now familiar term ‘bodybuilding’ (Brink, 1916). Gulick remained in post until 1900; Roberts departed after barely two years. The new course embraced anatomy, physiology, hygiene, physical diagnosis, elementary physics, the physiology of exercise and the use and management of gymnasia. To a significant degree, the inauguration of the programme signified the beginnings of physical education as a profession in the United States.

Gulick firmly believed the students were not being first and foremost trained to teach fitness and sports, rather he held that the prime task of the ‘gymnasium instructor’ was to ‘be an earnest soul winner’ (1888: 15). To illustrate this primacy Gulick devised the inverted equilateral triangle with ‘spirit’ supported on one side by ‘mind’ and on the other by ‘body’. A few years later, in 1897, the classic YMCA red triangle was publicly released.

As Gulick explained:

The triangle stands not for body, mind, or spirit, but for the man as a whole. It does not aim to express distinct divisions between body, mind, and spirit, but to indicate that the individual, while he may have different aspects is a unit …. Thus, the man who gives his time and attention largely to the education of his physical nature is violating the triangle idea, no less than the man who gives his time entirely to the intellectual, ignoring the spiritual and physical. (Gulick, 1894: 2)

Springfield students inspired in those early days by Gulick’s advocacy of this ideal adopted the triangle as their emblem in 1889; two years later the Training School followed in their wake. Gulick and others thereafter energetically set about trying to persuade the wider Movement to do likewise.

In Britain Arthur Yapp, then National Secretary of the British YMCA, during the first month of the First World War selected the red triangle as the means by which the movement’s activities within the compass of the British Empire was to be distinguished (Yapp, 1919). Thereafter, every one of the thousands of huts, tents, tea bars and restrooms run by the YMCA for military personnel and civilian war workers could be readily identified by the large red triangle displayed above its entrance and often painted on the roof and sides of huts or tents. In addition, all the hundreds of thousands of YMCA workers and volunteers wore a distinctive red triangle badge or armband when on duty; and all stationary, bulletins, crockery, gifts and the like incorporated the distinguishing red triangle. Not long afterwards the British YWCA followed suit by adopting in similar fashion a distinctive blue triangle. When the United States entered the war in April 1917 the American YMCA immediately replicated the British use of the red triangle as their emblem (Hopkins 1951: 487). Fittingly Gulick served under the Red Triangle with the US Army YMCA in France during 1917 and the early part of 1918. Shortly after returning from France, he died at Lake Sebago (Maine) during a visit to the camp, where in 1910, he and his wife Charlotte Gulick had launched a new national youth organisation the Camp Fire Girls of America – now known as Camp Fire (Miller, 2007).

As Head of the Physical Education Department, Gulick urged his colleague James Naismith to invent an indoor game that might be played by young men in halls of varying dimensions with minimal equipment and outlay. One that would, unlike most gymnastic pursuits and endeavours, foster collaboration, teamwork, and self-instruction (Ladd and Mathisen, 1999: 71). Naismith obliged by crafting ‘basket ball’ the first game of which was played at the YMCA Training School Springfield in December 1891. In addition to this ‘first’, it was William G. Morgan, an alumnus of Springfield, who in 1895, having observed that basketball was unduly energetic for many of the businessmen attending his evening sessions, embarked upon fashioning a less arduous alternative which he called ‘mintonette’. Gulick invited Morgan to bring some of his Hoyoke (Massachusetts) YMCA members to Springfield to demonstrate this new game in the same gymnasium where Naismith had first organised a game of basketball. Alfred Halstead, a member of the Springfield faculty, after the display helpfully advised that a more appropriate name for ‘mintonette’ might be ‘volleyball’ (Hopkins, 1951: 263). A third noteworthy Springfield sporting ‘first’ was that achieved by James Huff McCurdy, who arrived as an assistant to Gulick in 1896 and remained until 1916 (Karpovich, 1960). McCurdy introduced field hockey to the United States with the earliest recorded game to be played on American soil taking place at the College. Subsequently, McCurdy codified the rules in 1900. As an aside it should be noted that a staff team led by Naismith also formulated a game called ‘Team Ball’ designed to be a less full-bodied and costly version of American Football. Unlike Basketball it never caught-on and soon vanished without trace (Boyne, 1910).

During those early days Gulick may well have done more than anyone to put what later became known as Springfield College on the map (Putney, 2011). However, as a colleague remarked he soon ‘tired of classroom work’ (Burr, 1932: 12). The humble, but essential, task of teaching students it seems was not for him. Like many before, and since, for Gulick the college or university was primarily perceived to be a launching pad for personal ambition. Hence, by leaving swathes of teaching and administrative work to be shouldered by colleagues, Gulick retained the reserves of energy and time needed to devote himself to wider pursuits. Or, as he rather arrogantly put it, this enabled him to ‘lay eggs for other people to hatch’ (Nash, 1960: 60). Besides the achievements already mentioned, Gulick was, according to Chudacoff, the leading spokesman of the play movement in North America – ceaselessly promoting the development of facilities in urban localities (2007: 72). Undeniably he was also a key player in the movement to extend outdoor educational provision (Ford, 1989) and the drive to create new national youth-serving organisations such as the American Boy Scouts unveiled in 1910 (Macleod, 1983) and the Camp Fire Girls of America. Within the “Y” his influence was such that, according to Clifford Putney a historian of the Movement, he rose to become ‘the greatest of YMCA philosophers’ (2003: 69); the man who did more than any other to re-orientate its focus. As Putney goes on to explain ‘before Gulick, the “Y” had kept gymnastics subordinate to evangelism. After him, it held physical fitness, no less than religious conviction, responsible for leading men to Glory’ (op cit.: 72).

Following Reed’s departure in 1891, the designation YMCA Training School was adopted. During the same year a Correspondence Course was introduced along with a one-year post-graduate programme. The former grew apace and within twelve months enrolled over a hundred students. Most were resident in the USA or Canada, but a number were based in the United Kingdom, France, Denmark, Japan, and Switzerland. Four years later the Sunday School Workers and Pastors’ Helpers School was re-designated The Bible Normal College. Not long afterwards it became the first American seminary to admit women as students. Then, in 1902, it physically departed Springfield to merge with Hartford Seminary to create The Hartford School of Religious Pedagogy. Following a number of amalgamations and title changes in 2021 it became the Hartford International University for Religion and Peace.

Separation heralded a relaxing of the disciplinary regime imposed on students. Rules were dropped but, much to the annoyance of some, smoking, on and off campus, remained prohibited. Yet again the name changed in 1912 – this time to the International YMCA Training School. Staff believed the title better reflected the increasing number of overseas students in attendance – approximately a sixth then came from abroad (Doggett, 1943: 155). Overseas recruitment was aided by the funding, gifted by supporters, which enabled foreign candidates endorsed by their national Association to access scholarships which covered all or part of their tuition and board.

Prior to the creation of the Physical Education Department the curriculum of the School for Christian Workers had been dominated by religious subject matter of a ‘fundamentalist’ bent (Doggett 1943: 29). Clearly, if the new department was to supply competent practitioners capable of teaching physical education and managing diverse activity programmes, then a recalibration of course structures was needed to generate the space for the essential specialist elements. Gulick and his colleagues, who in part or whole, shared his reforming zeal set about creating a reworked cross-cutting curriculum. This was based on a belief that ‘the religious life’ included ‘everything there is in man – body, mind and spirit in complete whole’ (Gulick, 1918: 775). This focus led to both programmes shifting towards ‘the study of man’. The emergence of the additional route predictably precipitated a gradual change in the pattern of recruitment. Within a decade the two courses were approximately equal in size. Thereafter, the numbers joining the Physical Education Department year-on-year out-stripped those who came with the intention of becoming general secretaries’ post-graduation. In part this was because McCurdy undertook a vigorous recruitment campaign which stressed that the new degree was not exclusively designed to prepare men for entry into YMCA employment. By 1907 a fifth of those graduating opted for employment outside of the YMCA. More than a quarter of all Springfield alumni were by that date employed in ‘allied fields’ (Hall, 1964: 95). With each passing year this percentage increased as the demand for qualified physical educators equipped to work in other spheres such as schools, colleges and universities, and boys’ clubs grew (Doggett, 1943: 159).

In 1896 the two courses were extended in length to three years. Nine years later the State of Massachusetts granted the YMCA Training School independent authority to award degrees. Initially three-year BAs and one-year master’s degrees were offered in Humanics and Physical Education. Undergraduates on both completed a common core which had been introduced in 1901. This encompassed the study of: (a) the whole person – spirit, mind and body; and (b) ‘cultural’ areas – Biology, Psychology, Sociology and Religion. During 1896 a year-long Access Course for those lacking a High School Diploma was initiated. Subsequently in 1917 all under-graduate degrees were extended to four-years which allowed for new specialist routes including those on boys’, rural and industrial work to be incorporated into the programmes.

Humanics

Lawrence Doggett was appointed President of the YMCA Training School in 1896 and remained in post until 1936. Prior experience as the State Secretary of the Ohio YMCA convinced Doggett that secretaries were best recruited from amongst men who enjoyed a rich intellectual life and possessed a thirst for knowledge and a critical mind. Colleagues lacking those qualities, Doggett noted, usually ‘ran dry or became hack workers’ (Hall, 1964: 88). Springfield, he argued, if it was to eschew an analogous fate needed to circumvent becoming a training school priming students for ‘tasks already defined, goals already set’ (ibid., 87). Hence the importance he placed upon developing a suite of core cultural courses on, for instance, classical European literature, philosophy and singing. Implementing this was an audacious decision. Because as Hanford Burr, a teacher at Springfield from 1892 through to 1932, reminds us at the time it was generally assumed within the Movement that the college’s role was to afford training in an array of functional skills and ‘drill the students in the doctrines of the most conservative churches’ (1932: 78).

Doggett and Burr selected the name ‘Humanics’ to describe the approach embodied within the revised Secretarial and Common Core courses. The term Humanics which, up to this point in time had never been accorded widespread usage, was encountered in certain confined circles from the mid-nineteenth century onwards to depict a branch of knowledge relating to the study of human affairs. Probably it was first utilised by T. Wharton Collins who taught political philosophy at the University of Louisiana. Collins authored a text, published in 1860, entitled Humanics. This designated Humanics to be:

… the science of man …. It singles out man from the Zoological reign and makes him the subject of especial study. Which it analyses every detail of his organisation and essence, it attaches itself principally to his distinguishing characteristics, and seeks to find their synthesis. (Collins, 1860: 9 -10)

Doggett and Burr do not concede any familiarity with the work of Collins. Indeed, the former in his biography recalls how, after unsuccessfully trying to unearth an appropriate title for their revised Secretarial Course, Burr took down a dictionary and from it selected ‘Humanics’ as a term that might best serve to capture the essence of the new degree (Doggett, 1943). The proposed programme focussed on the study of human nature, affairs, and relations as well as practical administrative skills. Curiously they summarised the focus of Humanics by turning to the same quotation from Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Man Epistle II that Collins had utilised forty years earlier as the starting point for his text – ‘The proper study of mankind is Man’.

Springfield’s was the first Humanics degree and its introduction led to ‘an organised attack on the College and an attempt to drive out “the upsetters of the faith”’ (Burr, 1932: 78). Whether by design or not it created a permanent rift with the recently established Chicago Training School of the YMCA who had, following preliminary discussions, assumed that a common shared syllabus might be adopted by both. After discovering via a published notice, with no forewarning, that Springfield was heading down the Humanics route those hopes on the part of the Training School of the YMCA were dashed (Yerkes and Miranda, 2013). Given a text jointly written by Doggett and John Hansel President of the Chicago Training School of the YMCA (in conjunction with W. D. Murray) – Studies in Association Work: History, Principles, Business Management – had appeared a year earlier in 1905 it seems bizarre that Doggett did not see fit to alert his co-author as to Springfield’s intentions. Little wonder then that Hansel felt ill-used. Their text was devised to serve as a basic practice guide for students attending the two training schools and newly appointed YMCA staff. Formulated to be read by an individual to familiarise themselves with the workings of the Movement it was also structured so that it might be used as a ‘study-pack’. One which an established staff member might use as the basis of an introductory programme for colleagues and volunteers (see Doggett, Murray and Hansel, 1905).

The Springfield Humanics model was based on core topic areas or ‘aspects’ – the physical, social, philosophical, religious, psychological and the scientific (Burr, 1932: 74-75). The outlines below convey something of the broad reach of the syllabus:

- Physical Aspects: Biology, Anatomy, Physiology, Hygiene, Physical Diagnosis, Physical Education Methods.

- Psychological Aspects: General Psychology, Adolescent Psychology, Educational Psychology, Mental Hygiene, Pedagogy, Principles and Methods of Teaching.

- Religious Aspects: Bible, History and Philosophy of Religion, Comparative Religion, History of Christianity, Religious Education Principles and Methods.

- Social Aspects: Sociology, Economics, Social Ethics, History, Government, International Relations.

- Philosophical Aspects: Problems of Philosophy, History of Philosophy, Literature, Art, Drama, Music.

- Scientific Aspects: Chemistry, Physics, Natural Sciences (Geology, Botany, etc.).

In addition to taking the courses dedicated to teaching the ‘aspects’, students also completed specialist units relating either to physical education or secretarial work to secure a degree.

Springfield was the first college to conceive of a Humanics degree. Equally, it was, in all probability, also the first to close down a Humanics programme when it did so in 1927. According to Hall, the decision was arrived at because a growing number of students ‘who wished to teach academic subjects in schools or who were proceeding to graduate work’ found it difficult to get this degree recognised (Hall, 1964: 148).

Other American universities and colleges tracked Springfield’s lead and developed their own Humanics programmes. By the late 1980s in excess of 70 taught degree programmes accredited by the national co-ordinating body American Humanics (Ashcraft, 2001). Springfield having closed their free-standing Humanics degree nevertheless retained the subject as a one-semester freshman option and employed the concept as a vague ill-defined organizing ideal. Today Humanics has all but vanished from the academic map. American Humanics dissolved itself in 2011 to be promptly re-born as the Nonprofit Leadership Alliance. Affiliated institutions followed in lockstep by re-naming and re-calibrating their courses which henceforth focused on management, administration and leadership with a ‘non-profit’ gloss. Except that may not signify the final chapter in the story. Joseph Aoun, President of Northeastern University, in a text published in 2017 pressed the case for a ‘new discipline – “Humanics”- the goal of which is to nurture in our species’ unique traits of creativity and flexibility’ (2017: xviii). Aoun advocates the introduction of a supplementary university Humanics programme designed to teach and stimulate the ‘new literacies’ related to a deep understanding of technology, data and human relationships which he argues will help to make students ‘robot-proof’ (ibid.: 62). Oddly, like others before him, Aoun fails to acknowledge the existence of an earlier Humanics tradition. However, he, by a bizarre coincidence, quotes exactly same the line from Alexander Pope that T. Wharton Collins took as his point of departure in 1860; as did Doggett and Burr in 1906.

Chicago – beginnings

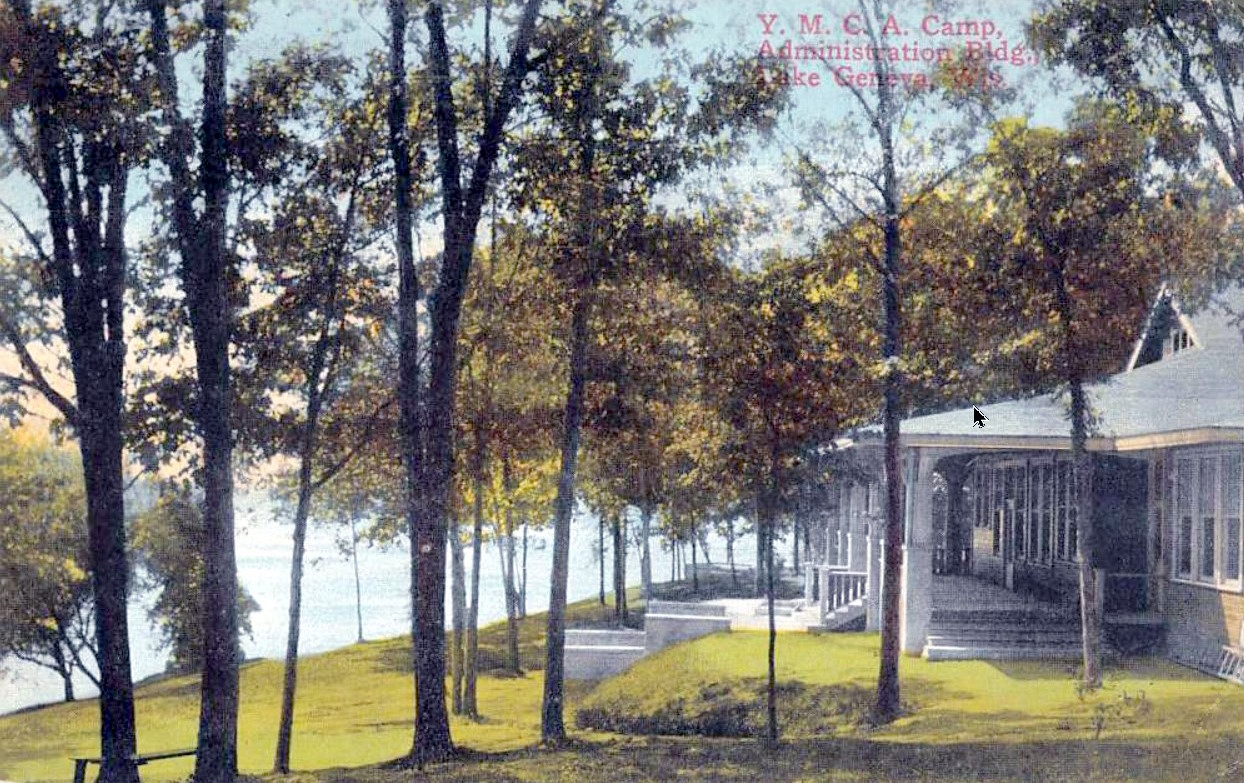

As the nation pressed westward so the YMCA followed. Come 1880 one in three Associations were located in states that either bordered the Mississippi or lay to the west of it. Robert Weidensall, once described as ‘the best-loved man in the Brotherhood’ (Hopkins, 1951: 122), was responsible for a great deal of that growth. Weidensall adjudged it was a shortage of well-trained and educated secretaries which seriously mired further expansion. So, in 1884, he and two close associates – Isaac Brown and William Lewis, planned an innovative training initiative to address this hindrance. They invited 57 colleagues to a meeting held beside Lake Geneva (Wisconsin) to inaugurate the Western Secretarial Institute (usually referred to within the Movement as simply the Institute). Brown, who in 1871 had established one of the earliest campus “YMCAs” at what was then the Illinois State Normal University and now Illinois State University (Ogren, 2005: 166), was at the time Illinois State Secretary. The Institute, which ran each year from May through to September, was formulated to offer current secretaries and members week-long training events and conferences. Land was purchased on what was subsequently designated Williams Bay and an extensive building programme commenced. Weidensall in 1889 outlined his ambitions for the Institute as follows:

What a law school is to a young man who aims to enter the profession of law, or what a medical school is to such a one as desires to practice medicine, so should this Institute be a place where young men could best study the work of the Association and especially of a General Secretary. (quoted Hopkins, 1951: 173-4)

The Institute sought to accomplish a range of outcomes. At the forefront was the training of secretaries, those already in post as well as prospective recruits. Each attendee was offered week-long taught courses relating to Associational work and Bible Study supplemented by open lectures, camp-fire meetings, entertainment, and leisure activities. Experienced secretaries and academics drafted in from Higher Education institutions were enlisted to act as tutors. Second, came the provision of discrete study programmes and sporting activities for members of the 700-plus College YMCAs then spread across the nation. The College “Y” proved extraordinarily popular, so much so that between the 1880s and 1920s approximately 25 to 30 per cent of all male college and university students were to varying degrees involved in their activities (Setran, 2007: 4). Third it was assumed these gatherings – by drawing Association men together – would facilitate the dissemination of good practice amongst serving secretaries, physical directors, boys’ club workers and education tutors. Finally, the camp setting was intended to foster ‘association’ and a sense of corporate identity. To this end, staff were encouraged to bring along their families who were offered an assortment of social and recreational activities.

Lake Geneva and the Institute were for almost half a century an unalloyed success. Attendances grew year-on-year until they peaked at 42,000 paying guests per annum during the early 1920s (Canady, 2016: 264). Predictably the concept was soon replicated. First by Dwight Moody, who served first as a Missionary, then as President, of the Chicago YMCA between 1861 and 1869 before becoming a full-time evangelist. In 1886 Moody launched a YMCA ‘College Student’s Summer School’ held in Northfield Massachusetts. It was so popular that it created a turning point in American evangelism as a consequence of the number of missionaries and evangelists enlisted from among attendees (Stratton, 2016). Others quickly followed. According to Richard C. Morse, in 1912 over a third of all YMCA employees attended one or more annual YMCA summer institutes and schools, and steps had by then been taken to promote ‘uniformity in the courses of study’ provided (1913: 161). Six welcomed white and black members but the seventh located at Blue Ridge (North Carolina) in the Deep South was ‘whites’ only. Black YMCA secretaries working in the South, who could not afford to travel ‘north’, were therefore excluded until they established in 1908 their own annual summer training school at Asheville (North Carolina). Three years later this transferred to Chesapeake Bay (Maryland). Unlike the other summer events, this initiative was not underwritten by a network of local Associations but was a national YMCA venture. Unfortunately, the Black Associations and branches, which post-1900 numbered approximately a hundred, lacked the resources to fund a permanent site akin to Lake Geneva. Therefore, what became known as the Chesapeake Summer School met in borrowed or rented accommodation (Mjagkij, 1994).

Weidensall, Brown and colleagues in 1890 took what was surely the next logical step by establishing a permanent year-round Training School of the YMCA. Brown, who remained Illinois State Secretary, initially undertook the key leadership role. From the outset the programme and syllabi were ‘built around the practical work of the YMCA’ (Yerkes and Miranda, 2013: 50). This meant it was formulated to furnish workers schooled to cultivate the ‘foursquare man’. The ‘founding fathers’ had no intention of allowing the sort of criticisms already being voiced in the Movement regarding the ethos of Springfield to be directed at them. Therefore, for example, they did not admit those who from the outset expressed a desire to pursue a career outside the YMCA in the wider charitable, education and social service fields. A practice that was widely held within sectors of the YMCA to have devalued the importance of Associational work at Springfield. Isaac ‘Eddy’ Brown, who had recently rebuffed the offer of a teaching post at Springfield, was appointed President of the Training School of the YMCA (Bowman, 1926: 46). An office he occupied whilst continuing to serve as State Secretary. John Hansel, initially recruited by Weidensall to manage and develop the Lake Geneva site, now added the Training School to his portfolio. Hansel was given the title of General Secretary but subsequently, after the amalgamation of the two entities, he in turn became President. To confuse matters Brown remained President of the College Board which took ultimate responsibility for the Training School and the Institute (Yerkes and Miranda, 2013: 70). Besides his two administrative posts Brown taught classes on the Bible, logic, philosophy, Association administration and church history (Bowman, 1926: 110). Hansel proved a capable organiser and adroit fund-raiser. But as Yerkes and Miranda note the boundaries between the respective roles of Brown and Hansel during this era was ‘never clear cut’ (2013: 76). In 1909 Brown resigned as Illinois State Secretary to become a full-time faculty member, serving as Dean of the Associational Department – a post he retained until he died in 1917. Previously Hansel had retired as President in 1905 to be replaced by Frank Burt. Burt remained in post until 1926. A graduate of Knox College, Burt had from the onset played a prominent role in the management of the Lake Geneva Institute. After graduating he had been a High School Principal prior to occupying a series of managerial roles within the YMCA. This included serving for eleven years as an area organiser for campus branches. Before becoming President, he had been in charge of the Institute and Training School’s Department of Secretarial Training (Yerkes and Miranda, 2013: 84). Like Hansel before him Burt was a skilled and effective fund-raiser.

The official opening of the Chicago Training School was 10th September 1890. Later that day Isaac Brown wrote to Charles K. Ober, head of the ‘Student Work’ Department within the International Committee, recounting that:

The first session of the Training School was held here this morning and was marked by a spirit of prayer and earnestness. Five students entered at the beginning, and one or two others are expected at once. These five come from three states and five different churches. Three of them enter the Physical Department and two the Secretarial. Two of them are high school graduates; two others, I think, have had a partial high school course. Three of them are men of experience in Association work and the fourth comes from a Board of Directors. The average age of the five is twenty-four years. We shall need to be much in communion with our Great Teacher if this work is the success we want it to be. (Ober, 1890)

The initial intake was 15 and the course comprised three terms plus attendance at the Lake Geneva summer school. Instruction in the early days was primarily provided by serving Secretaries. After merging with the Western Secretarial Institute in 1896 it became the Institute and Training School of the YMCA, a name retained until 1913 when it became the YMCA College. In 1896 the programme extended to two years by which time the annual intakes were circa 30. Around the same time, an agreement was made with Northwestern University (Evanston) and the University of Chicago permitting Institute and Training School graduates to transfer with credits onto their Liberal Arts degrees.

Brown and Hansel coordinated the unification of the Training School and the Lake Geneva Institute to form the Institute and Training School of the YMCA. This allowed the financially successful Institute to subsidise the Training School. Soon Brown added to Lake Geneva’s roster of week-long courses and conferences an intensive four-week educational programme taught by visiting academics and senior YMCA staff. Devoted to topics such as County Work, Physical Education, and Boys’ Work, these units were incorporated within the academic year for the full-time students which now comprised three terms at Chicago and a fourth at Lake Geneva (Yerkes and Miranda, 2013: 72). Integration meant those contemplating enrolment on the full-time training programme could attend the Lake Geneva segment to appraise the content, learn alongside current students and acquire credits. In 1911 two three-year Batchelor degrees were launched, one in Physical Work and another in Secretarial Administration. Henceforth, the minimum entry qualification became the possession of a high school diploma (Yerkes and Miranda, 2013: 116).

Originally it was intended to house the full-time course in the new Chicago Central YMCA modelled on the McBurney design. Unfortunately, this remained unfinished in 1890 so for the initial three years the course was accommodated in the Maddison Street YMCA, the largest of the five outreach branches then operating in the city. In 1893 staff and students transferred to a suite of classrooms and offices located on the eighth floor of the new 13-storey Central “Y” building; then the largest and most expensive Associational building in the USA.

From the outset, the Training School was overshadowed by the educational programme administered by the Central “Y” whose “Association College” was already running 24 evening classes and four University extension programmes (Dedmon, 1957: 119). Barely a decade later it was, in addition to the array of taught courses, dispensing over sixty-three English classes for various immigrant groups. By comparison, the Training School was always a small-time enterprise.

There the Training School remained until 1915 when, following a vigorous three-year fund-raising campaign orchestrated by the astute Burt, the $500,000 needed to construct a new independent campus became available (Dedmon, 1957: 209). Being based in the Central “Y” offered tangible benefits. It provided students with cheap but first-rate accommodation, access to a well-equipped library, the personal use of sports and leisure facilities, and on-site part-time employment. Chicago Central YMCA from the onset pledged to support the Training School with funds drawn from their endowment income, on condition that the new institution did not canvass for donations and legacy income within the boundaries of the city. However, those benefits were outweighed by serious disadvantages. First, prior to the early 1940s, Chicago Central YMCA operated a ‘whites only’ membership policy, although it did run a separate ‘blacks only’ branch elsewhere in the city. This made it problematic for Jewish and Black students to attend classes. Although they were entitled do so they could hardly have felt either welcomed or at ease within the overall setting. Second, the gymnasium and the indoor running track were shared with YMCA members so that access for teaching purposes was restricted to those times when the Central “Y” did not require exclusive usage. Even when the Institute and Training School did hold classes in the former it was obliged to do so in the presence of other users (Yerkes and Miranda, 2013: 94). Third, the swimming pool besides being primarily reserved for members, operated according to specific rules which denied access to either Jews or Negroes (Alcorn, 2007:97). Finally, the Institute and Training School lacked ready access to playing fields. These obstacles coalesced to make it impossible for it to replicate Springfield’s Physical Education programme. This, in part, may explain why the Institute and Training School programme from the outset had a dissimilar focus. It placed, for example, a heightened emphasis on familiarity with biological sciences and the management of facilities.

The first Director of Physical Work at the Institute and Training School was Henry F. Kallenberg – a Springfield alumni taught by Gulick and Naismith. Post graduation he became a YMCA Physical Director attached to the University of Iowa. Kallenberg earned himself a footnote in the history of basketball first by suggesting to Naismith that he cut a hole in the bottom of the net so the ball might fall through of its own accord after each successful shot. Second, because in 1896 he organised the first inter-collegiate basketball game (between the Universities of Iowa and Chicago). Before the game commenced Kallenberg also fixed the size of the teams to five thereby, it is claimed, creating the game’s modern format. Later in the same year, Kallenberg relocated to Chicago where he became an Assistant Physical Director at the Central “Y” and simultaneously studied medicine at Northwestern University. Whilst working at the Central “Y” he commenced teaching sessions at the Institute and Training School on a part-time basis. Shortly after graduating as an MD, he was appointed full-time Director of Physical Education at the Institute and Training School.

Initially, Kallenberg faced almost insurmountable challenges not merely with regards to securing access to facilities but in acquiring teaching apparatus. With no laboratories of his own, he was obliged to borrow on an almost daily basis basic equipment from his alma mater. However constrained the course might have been by the lack of facilities and equipment, it inevitably obliged the College to restructure the core programme to accommodate it. No longer was it feasible for the teaching to disproportionately focus upon the training of general secretaries. Kallenberg and his colleagues – notably Arthur Steinhaus who was to play a prominent role in researching links between lifestyle and health status – were committed to creating their own discrete model of tuition. It embraced group work, health promotion and the ‘broad’ foundations of Associational work as well as physical education. Crucially, it sought to fuse them in a distinctive way. As Steinhaus explained to his students:

You become physical educators when you use activities as means towards greater ends. As long as we are thinking of activities as ends in themselves, we are nothing but peddlers of physical activity…. You are here in this institution, in an environment that has always recognized this basically. (quoted Alcorn, 2007: 49)

Full degree awarding powers were conferred in 1911. Initially, undergraduate degrees in Association Science and Physical Education, and post-graduate degrees in Physical Education and Secretarial Education were offered. Association Science focussed on YMCA practice. However, it was not narrowly fixated on manufacturing YMCA secretaries. Indeed Mordecai Lee (2010), with some justification, views it as the proto not-for-profit management degree. It paid attention to the effective administration and governance of an organisation that did not ultimately have a singular fiscal measure whereby success or failure was to be assessed. Breadth was added, and horizons widened, via placements with settlement houses such as Hull House (founded by Jane Addams in 1889), Chicago Commons Settlement House (founded in 1894 by Graham Taylor then Professor of Applied Christianity at Chicago Theological Seminary and an early Trustee of the Springfield School for Christian Workers) as well as an array of boys’ clubs, adult education institutes and outreach projects working with neighbourhood gangs.

Whereas Springfield was situated in a small New England industrial town, the Institute and Training School of the YMCA was located at the heart of the second most populated city in North America. A metropolis of contrasting wealth and poverty, it was a melting pot riven by political, racial, religious and ethnic tensions, and ruled over by notoriously corrupt politicians. The resultant social tensions helped foster a maelstrom of reform activity, political radicalism, and religious evangelism. Perhaps it was, therefore, no accident that it was in Chicago, during decades which stretched from 1860 to the start of the Great War, that we witnessed, for example, the appearance of the first YMCA building and the opening of the earliest settlement house in America. We also find the origins of juvenile justice reform and the emergence of the University of Chicago as a pioneering centre for social work education, urban sociology and school reform. The YMCA, from the onset, had been pre-eminently a city-based organisation. Essentially it beheld the urban environment as dangerous and corrupting, antipathetic to religious beliefs, and healthy bodies and minds. City life was perceived as overflowing with temptation and sin against which young men needed to be protected from. The evangelicals who dominated the YMCA during the first half-century of its existence fervently believed the solution lay in conversion, one person at a time. The social problems which threatened to engulf the populace would, they held, be conquered via personal redemption, not by the reform programmes advocated by progressives, political campaigners and radicals. Consequently, the YMCA as an

organisation held itself aloof from any and all legislative causes, and while it encouraged civic engagement in its secretaries and its membership, the Associations themselves took no public position on any public issue. (Hodges, 2017: 55)

That position became increasingly difficult to sustain in the face of the rapid growth of what was known as the ‘social gospel’ or ‘social Christianity’ movement which gathered momentum post-1870 (Evans, 2017). The ‘social gospel’ urged Christians to actively engage with those social movements seeking to tackle the problems of urban deprivation. As Henry Emerson Fosdick, who during the Great War served as a YMCA worker, and wrote three popular religious texts published by the YMCA’s Association Press (1915, 1917, 1918) put it:

… any church that pretends to care for the souls of people but is not interested in the slums that damn them … [promotes] a dry, passive, do nothing religion in need of new blood (1933: 25).

Amongst numerous social gospel texts, pamphlets, and articles one, more than any other emerged from the throng. This was Charles Sheldon’s 1896 novel In His Steps: What Would Jesus Do? Wildly successful, with an excess of 100,000 copies sold during the first month of publication and over 50,000,000 editions purchased in the following decade, the novel’s final third is set in Chicago with much of the action occurring in a settlement. Chapter nine even contains an oblique attack on the YMCA for seeking to produce temperate, biddable, and obsequious employees who, as a consequence of their deference, were more easily exploited by unscrupulous employers. Graham Taylor, who briefly taught at Hartford Seminary before leaving for Chicago in 1892 (where he established the Chicago Commons Settlement whilst teaching full-time at the Chicago Theological Seminary) is another significant figure. He played a pioneering role in the development of the sociology of religion and devoted considerable time and energy trying to coax the YMCA into adopting the social gospel. At an international gathering held at the YMCA Training School (Springfield) in 1895 Taylor pleaded with his audience for a change of direction within the Movement:

To make of ourselves and our buildings centers for the social unification of the mixed and disunited hosts of young men, especially in the down town wards of our cities; to make of our meetings and educational classes schools in which the young men of the nation may study and learn their social and civics rights and duties as a part of the citizenship and religion; to raise up an intelligent body of young men who will be too loyal to the commonwealth both of our country and of the kingdom of God to engage in the fratricidal strife of class warfare; to push the Association movement into lodging houses and labor unions, street life and recreative rendezvous of young men …. So only can we fulfil our supreme duty and opportunity in the “present crisis” to become “peace makers” and leaders of our common Christianity in saving the souls and the social relations of America’s young manhood. (quoted Wade, 1964: 114)

Taylor’s entreaty failed to secure the impact he and others hoped for. Within a decade he had, to all intents and purposes, given up on the YMCA and moved on. Others followed in his wake, but enough adherents to the social gospel remained for the tensions and debates to persist. Certainly, they did so within the Chicago Institute and Training School (Alcorn, 2007). Irrespective of, or perhaps in response to, these pressures, the YMCA nationally from the late 1890s set about extending the reach of its work. Consequently, if the degree programme was to remain germane it to was obliged to widen its range of options. Gradually it did so by adding specialisms to the programme such as Railroad, Industrial, Boys’, Camp and Play Work.

This opening out into new areas, most of which were far more welfare-orientated than mainstream secretarial work, required a re-alignment in relation to programme content. A solution to this challenge was to shift the focus of the teaching from theological and religious topics towards core elements of practice and the creation of new undergraduate routes. For Edward Jenkins, who was President of the Chicago Institute and School from 1926 to 1936 and who had served as a General Secretary in New York, this entailed an espousal of ‘informal education’ which he viewed as the common thread coursing through the various aspects of YMCA work, adult education and most, if not all, youth-serving organisations.

One area of intense growth within the Movement during the decades spanning the First World War was boys’ work with those aged 14 to 16. Eventually, this led to the introduction by the YMCA College in 1928 of a Bachelor in Administration of Boys’ Clubs. Almost certainly this was the earliest undergraduate degree in youth work offered anywhere in the world.

Besides the provision of activities, many YMCA practitioners and settlement workers in the fields of youth work, community organising, and social work seized upon the idea that an effective and efficient means of intervention was via the creation or nurturing of groups. This involved the worker in seeking to proactively influence the collective for the better. As Burr noted as early as 1909 this approach was perhaps best ‘described as group work rather than mass work or even individual work’ (1909: 35). This modus vivendi had a long history but the label ‘group work’ did not emerge until the onset of the twentieth century (Smith, 2004). It was during the early years of YMCA boys’ work we probably encounter the untheorized beginnings of ‘group work’. Interventions overwhelmingly embarked upon by untrained staff or volunteers. Consequently, as Burr found:

Some boys’ work directors have had a bad case of “gangitis”. They seem to think that, having gotten a lot of boys together in various groups, all they have to do is let the pot boil. It usually does but the cooking is poor. (1909: 39)

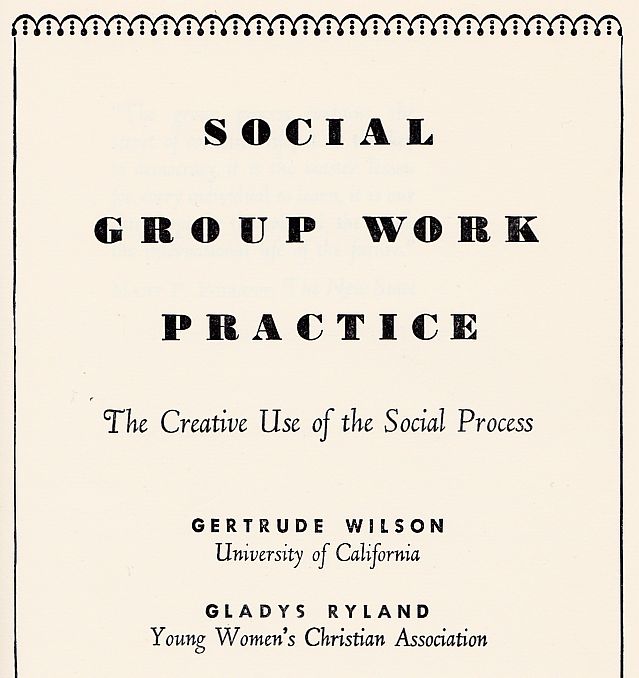

It was to address failings such as this and related challenges that key members of the YMCA College staff team post-1920 developed programmes linked to what they termed social group work (see Reid 1981). A substantial proportion of the key figures involved in the elaboration of social group work either taught at the college (Hedley Dimock, Charles E. Hendry, Everett Du Vall, and Harleigh B. Trecker) or worked closely with it. Notably the latter included Gertrude Wilson and Gladys Ryland (Chicago YWCA), Neva Boyd (Hull House Settlement) and the doyen of group work theorists Grace Coyle who was employed by the YWCA, in various capacities from 1917 to 1934. The staff team’s reasons for embracing this model was that:

Informal education leaders entered their fields with the assumption that small group face-to-face encounters provided the best context within which people, including children, could solve their common problems or set new goals. A well-functioning small group was seen as a powerful agency for change. Consequently, under the guidance of a skilled guide, these groups and their members were fully equipped to establish and pursue appropriate goals and/or solve problems encountered in their paths. With help, young people in particular, could be led to discover, intelligently respond to and better manage the challenges and opportunities they faced. (Yerkes and Miranda, 2013: 134)

The decision reflected a wish to equip graduates with a skill set that would enable them to thrive in demanding settings.

This was an era when youth-serving organisations frequently found themselves catering for numbers rarely if ever, encountered today. For example, Chicago Central YMCA at the start of the 1930s recorded over six million attendances at its facilities in a single year, whilst the summer residential camps catered annually for almost six thousand boys (Dedmon, 1957: 250). Towards the end of the 1930s, the annual membership of the Chicago YMCA was almost 38,000 (ibid. 284). The boys’ club run by Hull House Settlement, close by the College, which furnished numerous student placements, had a membership of 1,500 whilst the weekly adult attendance was in excess of 9.000 (Alcorn 2007: 14). It was within organisations such as these that students were required to undertake placements and voluntary work and where a majority eventually found employment. Social Group Work flourished for approximately three decades up the mid-1950s. During that brief interval, a rich array of texts emerged, the most significant of which was in all likelihood Wilson and Rylands’ Social Group Work Practice published in 1949, which drew extensively upon the author’s experiences as YWCA workers in Chicago.

Many of the remaining texts were published by the YMCA’s Association Press. During that thirty-year period social group work became not merely the core theoretical element within programmes designed for those intending to take up posts with youth-serving organisations, settlements and adult education projects but a key element within over half of all American social work education programmes (Wilson, 1956). Such was the ascendent position of George Williams College in the field that it was frequently referred to as ‘the group work school’ (Alcorn, 2007: ix). As late as 1952 the then President Harold Coffman reiterated that ‘Curriculum at George Williams is primarily centred around a group work orientation’ (Coffman quoted Alcorn, 2007: 20).

The appearance during 1949 of the Wilson and Rylands’ text was probably social group work’s high-water mark for only one significant work on the subject appeared after that date – Gisela Konopka’s Social Group Work: A Helping Process (1965). During the 1950s social group work endured a period of rapid and seemingly irreversible decline (Tropp, 1978; Andrews, 2001). It vanished from the syllabus of Social Work training programmes as they set aside group work to focus wholly on the individualistic case work model of intervention (Konopka, 1960). Whilst many youth-serving organisations saw little need for social group work as they focussed their attention ‘exclusively’ on the provision of ‘recreational’ programmes and activities (Konopka, 1963: 182). This shift meant it was within that sector that resource management and, to a lesser extent, developmental psychology came to the scholarly fore.

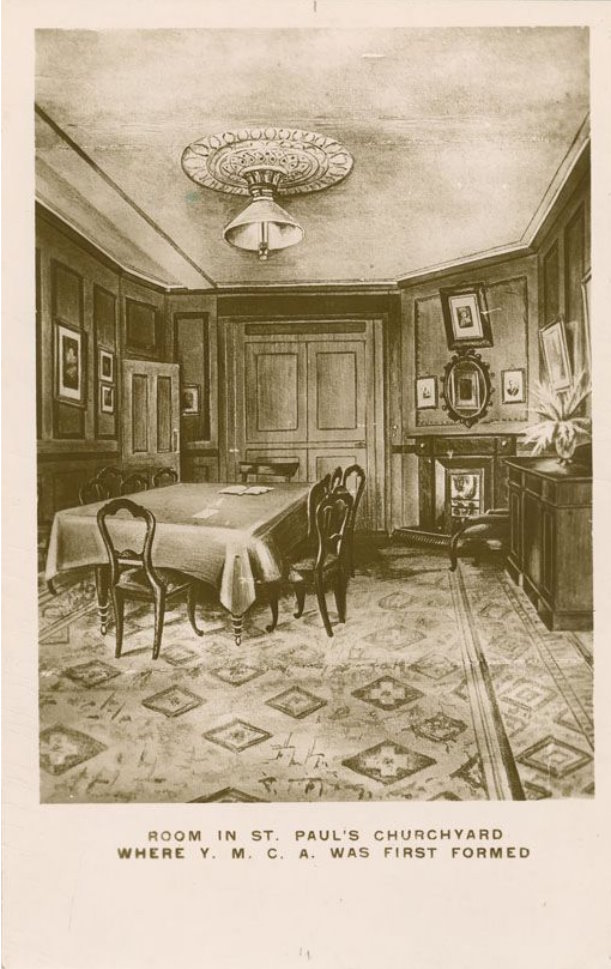

The YMCA College in 1915 moved to new premises in the Hyde Park area of Chicago, close by the University of Chicago and Hull House. Shortly afterwards the admission criteria were brought into line with those of the neighbouring universities. Relocation meant it became more realistic for Black and Jewish students to attend. The purpose-built, 84-acre campus contained a sports field, running track, two gymnasiums, a swimming pool, a library, ample classrooms and residential accommodation for a hundred students. At the time of the transfer the YMCA College had 179 students, yet the cafeteria was designed to accommodate 1,000 at a sitting. Self-evidently, it was intended that the campus would serve as home to a fast-growing institution. In 1921 a facsimile of the room located in 72 St Paul’s Churchyard (London) where George Williams convened the inaugural meeting that resulted in the formation of the YMCA was installed within the new premises. Subsequently, the original was destroyed during an air raid in 1944 which gave an added poignancy to this unique memorial. In 1965, when George Williams College moved again to new premises, the replica, accurate in almost every detail with duplicate furnishings, a carefully constructed uneven floor and appropriately sagging windows and doors, was transferred to the Lake Geneva site. There it remains safely intact within the Beasley Campus Center.

At the time of the relocation to Hyde Park the student body was taught by 17 staff who were augmented by tutors ‘borrowed’ from the University of Chicago. The YMCA College still retained ownership of the William’s Bay site which continued to host the summer programme, which helpfully furnished a prized income stream. The name changed yet again in 1933 this time to George Williams College. Primarily to distinguish it from the far larger Chicago Central YMCA College (founded in 1922) which concentrated on providing business and engineering courses. Chicago Central YMCA’s decision, made around this time, to cease its financial support of the YMCA College and to no longer guaranteed students part-time employment essentially ended the long-running partnership.

Nashville

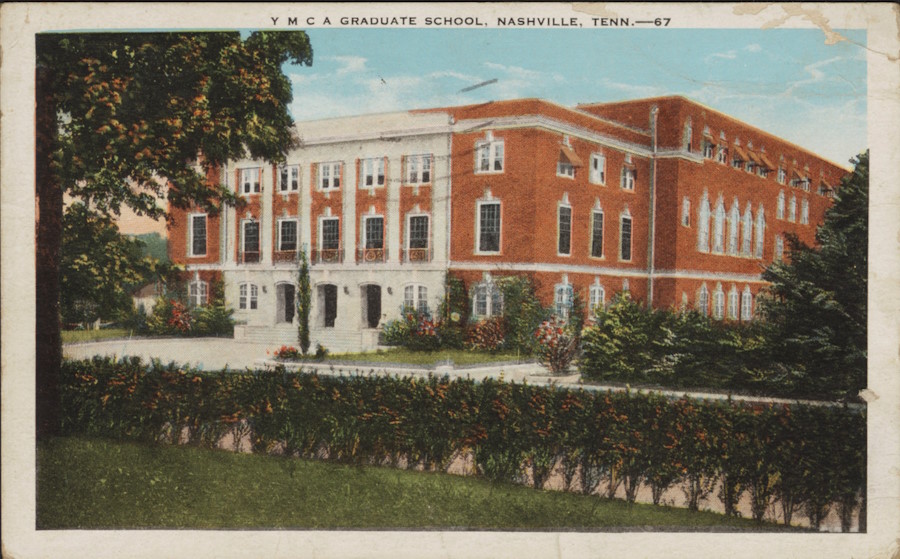

Between 1919 and 1936 there was in the United States a third YMCA training agency. This was based in Nashville (Tennessee). Originally launched as the Southern College of the Young Men’s Christian Association it became the YMCA Graduate School in 1927. The School was principally the creation of Willis Duke Weatherford, an ordained Methodist minister, who from 1902 to 1919 was the YMCA Supervising Secretary for the 200-plus affiliated college Associations in the South and Southwest. After visiting Lake Geneva in 1894 Weatherford set about creating a similar Institute for the South where all but a handful of the salaried ‘Y’ workers were not only untrained but tended to view their posts as transitory employment (Antone, 1973). Twelve years later Weatherford had procured sufficient funding to purchase 1,500 acres besides Blue Ridge Mountain (North Carolina) and commence building work. Blue Ridge Summer Training School opened in 1907. At its peak during the early 1920s Blue Ridge, dominated by its substantial residential and teaching centre Lee Hall, attracted up to 32,000 paying guests per annum.

This was a ‘white’s only’ venue. First, the Jim Crow laws, dating from the 1860s and which survived in whole or part into the 1960s, enforced strict segregation in those states, including North Carolina, which once comprised the Confederacy. These laws which applied to all educational and social facilities effectively prevented any manifestation of racially mixed education. Second, irrespective of the laws themselves, it is unlikely that few, if any, Associations, secretaries, and college “Y” branches located in the old Confederacy would have lent their support if it had been otherwise. Third, it was not merely the legal system which ‘administered’ segregation, but a formal and informal network of vigilantes. An example here was the unknown individuals who, after Weatherford invited a Black speaker to address a conference at Blue Ridge, burnt down one of the buildings as a warning (Dykeman, 1966). Yet Weatherford, an opponent of segregation, was determined despite the odds against him to bring about lasting change via education and dialogue. For example, in 1917, during an exceptionally tense period when racial conflict and lynching appeared to be on the rise, Weatherford convened a conference at Blue Ridge attended by 48 educators, ministers, social workers, medics, church workers, judges, club workers, public officials and YMCA and YWCA personnel. Black and white, men and women drawn from nearly every Southern state were present. This was an audacious enterprise and at the time possibly a unique one (Combs, 2004: 107). Such events which regularly took place at Blue Ridge might nowadays seem low-key and modest, but in the context of their era, they were extraordinary. As Canaday reminds us, this was indeed a special place:

From 1912 to 1952 Blue Ridge was one of the very few southern places where the subject of race could be talked about in an open, tolerant, rational and intelligent context. Indeed, in the South of the 1910s and 1920s, there were no other similar arenas of the size and scale of Blue Ridge where such radical conversations were held. (2016: 74)

Weatherford was a religious and political liberal who persistently strove to temper the harsh realities of a segregationist legal code. As the organiser of the first Southern Sociological Congress, Weatherford faced-down pressure from certain attendees, the local media, and the owners of the chosen venue to set apart or exclude Black delegates. His solution was to move the event to a nearby Methodist Church and bid those unwilling to sit alongside Black delegates to depart. At Blue Ridge, Weatherford regularly invited Black academics and theologians to address the secretaries and young students; he also included in the syllabus courses on race relations. In 1908 he met with a group of white and Afro-Americans to discuss a textbook for use in these courses and by the two existing YMCA Training Schools. As a direct consequence of these gatherings Negro Life in the South: Present conditions and needs appeared in 1911 under the imprimatur of Association Press (Weatherford, 1911). In 1934 another major text grew out of this collaboration Race Relations: Adjustment of Whites and Negroes in the United States, jointly authored by Charles Spurgeon Johnson, a leading Black sociologist, and Weatherford.

Willis Duke Weatherford resigned in 1919 as a Supervising Secretary to concentrate on establishing the Southern College of the Young Men’s Christian Association (Nashville). Located originally in rooms rented from Vanderbilt University School of Religion, and with students living in accommodation managed by the same university, it commenced with five staff, two of whom were part-time, and 15 students. Southern College was positioned across the road from the main buildings of Vanderbilt University and flanked by Scarritt College for Christian Workers on one side and by the George Peabody College for Teachers on the other. The choice of location was not by happenstance. Southern College students were encouraged to devote up to half of their time-tabled hours completing graduate or post-graduate courses dispensed by those three adjacent institutions. Vanderbilt provided courses on all the mainstream branches of the social sciences and theology. Peabody taught the full spread of education topics, and the Knapp School of Country Life, which was attached to it, offered specialist teaching on rural education and economy. Finally, Scarlitt taught degrees in ‘Community and Family Service’, ‘Social Work’ and ‘Religious Education’ which afforded students entrée to yet more specialist units (Van West, 2018). Southern College, by way of recompense, provided students from the other institutions access to units relating to physical education and race relations which they did not teach. All the partners admitted only white applicants.

Initially, two degrees were offered by Southern College: these were a Bachelor and a Master of Arts. Both were structured ‘to prepare students to administer YMCA facilities, provide a thorough grounding in religious instruction and offer graduate-level liberal arts courses’ (Combs, 2004: 99). The BA, however, was merely a temporary component incorporated solely to facilitate the launch and help provide an initial throughput of post-graduate students. Once graduate applications rose, it was discarded thereby enabling the name to change in 1927 to The YMCA Graduate School. By this time Weatherford had raised the $500,000 needed to construct a new free-standing building to house The YMCA Graduate School close by the pre-existing location. A third degree was added to the roster shortly after the launch. This was a doctorate in Physical Education. At that point in time, Southern College was one of only three institutions offering this terminal degree (the others being Columbia University and New York University). During its lifetime The YMCA Graduate School awarded five of these doctorates.