Plato on education. In his Republic, we find just about the most influential early account of education. His interest in soul, dialogue and continuing education continues to provide informal educators and pedagogues with rich insights.

Plato on education. In his Republic, we find just about the most influential early account of education. His interest in soul, dialogue and continuing education continues to provide informal educators and pedagogues with rich insights.

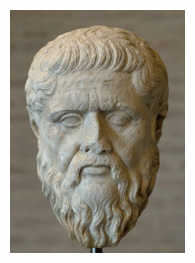

Picture above: The School of Athens by Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (Raphael) – Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Plato is the central figure in red. The second image of Plato is also public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

________

Plato (428 – 348 BC) Greek philosopher who was the pupil of Socrates and the teacher of Aristotle – and one of the most influential figures in ‘western’ thought. He founded what is said to be the first university – his Academy (near Athens) in around 385 BC. Plato’s early works (dialogues) provide much of what we know of Socrates (470 – 399BC). In these early dialogues we see the use of the so called Socratic method. This is a question and answer form of arguing with an ‘expert’ on one side and a ‘searcher’ on the other. In the dialogues, the questioning of the expert by the ‘searcher’ often exposes gaps in the reasoning. Part of this can be put down to Plato’s dislike of the Sophists (particularly as teachers of rhetoric) and his concern that teachers should know their subject.

The ‘middle period’ of Plato’s work is also characterised by the use of dialogues in which Socrates is the main speaker – but by this point it is generally accepted that it is Plato’s words that are being spoken. We see the flowering of his thought around knowledge and the Forms, the Soul (psyche and hence psychology), and political theory (see, especially, The Republic).

The ‘late period’ dialogues are largely concerned with revisiting the metaphysical and logical assumptions of his ‘middle period’.

One of the significant features of the dialogical (dialectic) method is that it emphasizes collective, as against solitary, activity. It is through the to and fro of argument amongst friends (or adversaries) that understanding grows (or is revealed). Such philosophical pursuit alongside and within a full education allows humans to transcend their desires and sense in order to attain true knowledge and then to gaze upon the Final Good (Agathon).

Perhaps the best known aspect of Plato’s educational thought is his portrayal of the ideal society in The Republic. He set out in some detail , the shape and curriculum of an education system (with plans for its organization in The Laws). In the ideal state, matters are overseen by the guardian class – change is to be avoided (perfection having already been obtained), and slaves, and craftsmen and merchants are to know their place. It is the guardian class who are educated, merchants and craftsmen serve apprenticeships and slaves…

Plato’s relevance to modern day educators can be seen at a number of levels. First, he believed, and demonstrated, that educators must have a deep care for the well-being and future of those they work with. Educating is a moral enterprise and it is the duty of educators to search for truth and virtue, and in so doing guide those they have a responsibility to teach. As Charles Hummel puts it in his excellent introductory essay (see below), the educator, ‘must never be a mere peddler of materials for study and of recipes for winning disputes, nor yet for promoting a career.

Second, there is the ‘Socratic teaching method’. The teacher must know his or her subject, but as a true philosopher he or she also knows that the limits of their knowledge. It is here that we see the power of dialogue – the joint exploration of a subject – ‘knowledge will not come from teaching but from questioning’.

Third, there is his conceptualization of the differing educational requirements associated with various life stages. We see in his work the classical Greek concern for body and mind. We see the importance of exercise and discipline, of story telling and games. Children enter school at six where they first learn the three Rs (reading, writing and counting) and then engage with music and sports. Plato’s philosopher guardians then follow an educational path until they are 50. At eighteen they are to undergo military and physical training; at 21 they enter higher studies; at 30 they begin to study philosophy and serve the polis in the army or civil service. At 50 they are ready to rule. This is a model for what we now describe as lifelong education (indeed, some nineteenth century German writers described Plato’s scheme as ‘andragogy’). It is also a model of the ‘learning society’ – the polis is serviced by educators. It can only exist as a rational form if its members are trained – and continue to grow.

Key texts:

Plato (1955) The Republic, London: Penguin ((translated by H. P. D. Lee).

Biographical material:

Hare, R. M. (1989) Plato, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Succinct introduction that covers a good deal of ground.

Websites: There are thousands of sites that have some reference to Plato. As a starting point you could look at one of the potted biographies: Plato briefly introduces his life and work and then provides links into his works. Try The Republic.

© Mark K. Smith First published May 8, 1997