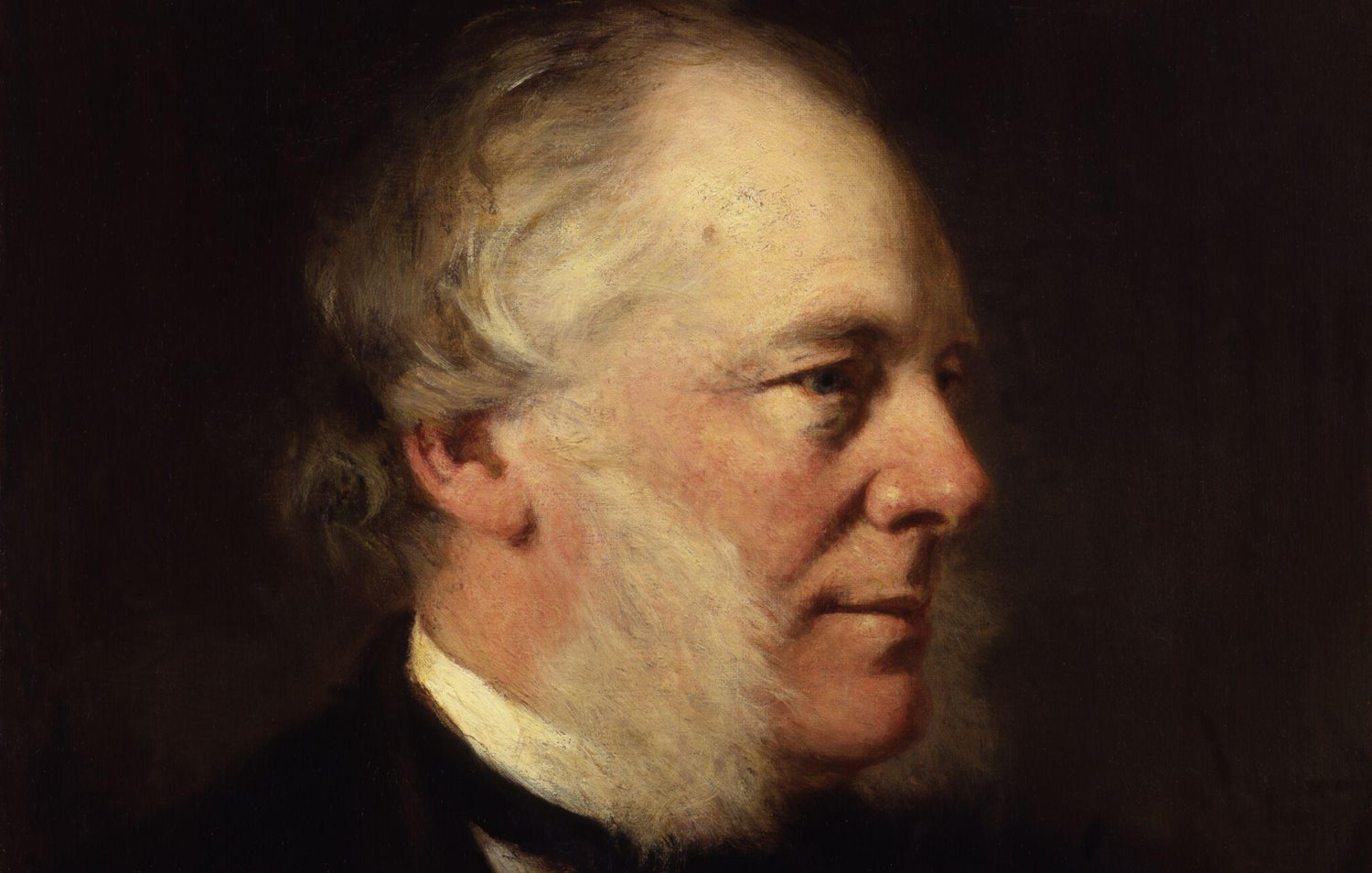

Samuel Smiles and self-help. Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help is said to have reflected the spirit of its age. It also proved to be a best-seller – with more than a quarter of a million copies sold by the time of Smiles’s death. Arguing for the importance of character, thrift and perseverance, the book also celebrates civility, independence and individuality. As such, it reflects concerns and values that were central to working-class efforts at self-improvement and study in the second half of the nineteenth century. Here we provide a brief introduction.

contents: introduction · self help · conclusion · references · how to cite this piece · read chapter 1 of self help · read chapter 1 of self help

Samuel Smiles (1812-1904) the Scottish writer and social reformer is one of the best-known figures of the Victorian era. Born in Haddington he studied medicine (at Edinburgh) and became a doctor in his home town – earning relatively little money. Later he worked as a surgeon in Leeds. In 1838 Samuel Smiles became editor of the Leeds Times – a radical journal. He used this position to argue for various causes including women’s suffrage and parliamentary reform. However, Samuel Smiles, while endorsing several aspects of the Chartist position, was generally cautious about it. His radicalism gradually took a more liberal and individualistic tone (Matthew 2004). Political reform was no longer enough, change required individual reform. In 1842 he resigned from the Leeds Times to lecture and undertake ‘literary hack work’ (op. cit.). He married Sarah Holmes in 1843 and was to have three daughters.

Whilst in Leeds Samuel Smiles met George Stephenson (the railway engineer) and within a relatively short time (after Stephenson died in 1848) began writing his Life (published in 1857). Smiles was also involved in the formation of the Leeds and Thirsk Railway in 1845 and became its assistant secretary. In 1854 the family moved to London when Samuel Smiles became secretary of the Southeastern Railway – a position he held for 12 years. In 1866 he became president of the National Provident Institution. He resigned in 1871.

Self-Help grew out of a popular lecture (which was first given at a mutual improvement society) (Matthews 2004). The manuscript was initially rejected by one publisher – Routledge – but was picked up by John Murray, with whom Samuel Smiles was to have a long and fruitful relationship. This included writing a history of the publisher (published in 1891). Smiles developed the themes of Self-Help in several other publications including Character (1871), Thrift (1875), Duty (1880) and Life and Labour (1887). He also wrote a large number of other books including Lives of the Engineers (4 volumes 1861, 1862), The Huguenots and various biographies including one on Josiah Wedgewood (1894).

In later years Samuel Smiles became more conservative. His individualistic orientation also fell out of favour – with John Murray turning down ‘Conduct’ the last book in the series begun by Self-Help (Matthews 2004). From 1871 Smiles suffered from various illnesses and began to slow down. He died in 1904 and was buried in Brompton Cemetery.

Self-Help

The purpose of Self-Help was, as the subtitle indicates, ‘to illustrate and enforce the power of George Stephenson’s great word – PERSEVERANCE’ (Smiles 1905: 226). According to Asa Briggs (1958: 9) the book was ‘a skilful blend of precept and anecdote’. It stood out from other books of a similar nature because of its, ‘neatness of phrase, wide range of illustrations, the variety of experiences of its author and his remarkable ability to say something of interest and importance to generations of “ordinary” men and women’ (Briggs 1958: 10). In a classic paragraph (from Chapter 1 of Self-Help – reproduced below) he also made the case for informal education and autodiadaxy:

Daily experience shows that it is energetic individualism which produces the most powerful effects upon the life and action of others, and really constitutes the best practical education. Schools, academies, and colleges, give but the merest beginnings of culture in comparison with it. Far more influential is the life-education daily given in our homes, in the streets, behind counters, in workshops, at the loom and the plough, in counting-houses and manufactories, and in the busy haunts of men. This is that finishing instruction as members of society, which Schiller designated “the education of the human race,” consisting in action, conduct, self-culture, self-control,—all that tends to discipline a man truly, and fit him for the proper performance of the duties and business of life,—a kind of education not to be learnt from books, or acquired by any amount of mere literary training.

Conclusion

Since Self-Help appeared it, and much of Samuel Smiles’s work, has often been treated rather simplistically as an apology for Victorian middle-class values. However, as Peter W. Sinnema has pointed out, Smiles was at the time an ‘uncompromising critic of rapacity and complacent affluence’ (2002: viii). Further, he advocated virtues, ‘central to the projects of other nineteenth-century institutions that actively encouraged the cultivation of the intellectual and moral working-class self: the mechanics’ institutes, public libraries, people’s colleges and lyceums’ (Sinnema 2002: vii). Matthews (2004) has suggested the book ‘reflected an association of the moral aspects of the Calvinism Smiles had been taught as a child with the educational values of the Unitarians and the radicalism of the Anti-Corn Law League’. In some ways, it was odd that Samuel Smiles – the critic of many ‘conventional’ middle-class values and social reformer – should end up as a much admired historical figure for the Tory right during the 1980s (See Jarvis 1997).

References

Briggs, Asa (1958) ‘Self-Help. A centenary introduction’ in Samuel Smiles (1958) Self-Help. The art of achievement illustrated by accounts of the lives of great men. London: John Murray.

Jarvis, Adrian (1997). Samuel Smiles and the Construction of Victorian Values. Thrupp: Sutton Publishing.

Matthew, H. C. G. (2004) ‘Smiles, Samuel (1812–1904)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press; online edn, May 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/36125, accessed 7 July 2009].

Sinnema, Peter (2002) ‘Introduction’ to Samuel Smiles Self Help. Oxford: University of Oxford Press.

Smiles, Samuel (1857) The Life of George Stephenson, Railway Engineer. London: John Murray.

Smiles, Samuel (1859) Self-Help with Illustrations of Conduct and Perseverance. London: John Murray.

Smiles, Samuel (1861 1862) Lives of the Engineers : with an account of their principal works comprising also A history of inland communication in Britain.3 volumes. London: John Murray.

Smiles, Samuel (1867) The Huguenots: Their Settlements, Churches and Industries in England and Ireland. London: John Murray.

Smiles, Samuel (1871) Character. London: John Murray

Smiles, Samuel (1875) Thrift. London: John Murrary.

Smiles, Samuel (1880), Duty : with illustrations of courage, patience, & endurance. London: John Murray.

Smiles, Samuel (1887) Life and Labour or, characteristics of men of industry, culture and genius. London: John Murray.

Smiles, Samuel (1891) A Publisher and his Friends: Memoir and Correspondence of the Late John Murray. 2 volumes. London: John Murray.

Smiles, Samuel (1894) Josiah Wedgwood F.R.S. His personal history. London: John Murray.

Smiles, Samuel (1905) The Autobiography of Samuel Smiles, LLD, edited by T. Mackay. London: John Murray.

Link

Project Gutenberg – to download full texts of several key works by Samuel Smiles.

Acknowledgement: The picture of Samuel Smiles is believed to be in the public domain because copyright has expired and was sourced from Wikipedia Commons

How to cite this piece: Smith, Mark K. (2009). ‘Samuel Smiles and self-help’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [www.infed.org/thinkers/samuel_smiles_self_help.htm].

© Mark K Smith 2009