Informal and non-formal education, colonialism and development. The place of informal and non-formal education in development – the experience of the south.

Contents: introduction · the indebted south · education in the south · the question of colonialism · non-formal and informal programmes · literacy programmes · conclusion: informal and non-formal education and development · further reading and references · links · how to cite this piece

Here we examine some of the arguments surrounding the place of informal, non-formal and community education in development, particularly in the South and ask whether such educational initiatives act as agents of colonialism (or to be more accurate neo-colonialism). To do this we need to review briefly the general economic and social position facing Southern countries; the significance of the debt/aid relationship; and the nature of colonialism.

As a way of exploring questions around the contribution of informal and non-formal education I want to look at the changing emphasis on literacy within many Southern countries.

The indebted south

The vast majority of countries in the South have remained locked into positions in the international economic order which impose constraints on national decision-making of a quite different magnitude from those which affect most countries in the North. In the 1980s these inequalities in power and influence were brought into sharper focus by a global recession and a widespread debt crisis among developing countries. A study covering 107 developing countries, of which forty-one were categorized as ‘least developed countries’, found that between 1980 and 1990 there were significant falls for most ‘developing countries’ in gross domestic product, public expenditure and private consumption per head (Graham-Green 1991). The latter decreased in 81 per cent of the least developed countries and in 64 per cent of other developing countries. The United Nations (2000) reports that more than 2.8 billion people, close to half the world’s population, live on less than the equivalent of $2/day. More than 1.2 billion people, or about 20 per cent of the world population, live on less than the equivalent of $1/day. South Asia has the largest number of poor people (522 million of whom live on less than the equivalent of $1/day). Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest proportion of people who are poor, with poverty affecting 46.3 per cent or close to half of the regions’ population (United Nations Briefing).

Debt service (the amount of money paid in interest and other charges on loans) increased to claim a greater share of export earnings in 87 per cent of the least develop ed countries and in 84 per cent of the other developing countries during the 1980s. For a number of states in Latin America, and for some in Africa, difficulties in repaying international loans had already started in the 1970s, with the 1973 oil price rises bringing the first major shock to more fragile economies.

| Exhibit 1: Debt increases and decreases |

In sub-Saharan Africa, GDP per capita had grown at over 3 per cent a year between 1965 and 1973 but had stagnated between 1973 and 1980. Between 1980 and 1988 it fell by about 25 per cent. More recent figures (United Nations 2000) reveal that the top fifth (20 per cent) of the world’s people who live in the highest income countries have access to 86 per cent of world gross domestic product (GDP). The bottom fifth, in the poorest countries, has about one per cent. In 1998, for every $1 that the developing world received in grants, it spent $13 on debt repayment (United Nations Briefing).

Education in the South

Between 1950 and 1970, the numbers of those enrolled in schools rose dramatically on a global level, and literacy levels rose, though not as rapidly as had been hoped. Rural communities, and especially rural women, still missed out on educational opportunities. None the less, the hope was that access to education would deliver many benefits: for the nation, a skilled work force to contribute to economic development, national unity and social cohesion, and in some countries, popular participation in politics. For the individual, it promised an escape from poverty, greater social prestige and mobility, and the prospect of a good job, preferably in town. In practice these hopes were often unfulfilled, particularly among the least privileged social groups, but they remained powerful aspirations.

In many countries of the South the debt crisis of the 1980s ended an era of unprecedented growth for education. Countries severely affected by the economic crisis, often compounded by military and political conflict, saw the numbers of children enrolling in school fall, and a marked increase in dropout rates among children who do start school. They saw a decline in opportunities for young people and adults to participate in education. More recently, the situation has generally improved in a number of countries – although, most significantly, not in sub-Saharan Africa. The United Nations (2000) reports that worldwide:

The number of children in school has risen significantly, from 599 million in 1990 to 681 million in 1998.(However, there are major regional disparities- school enrolments went down in sub-Saharan Africa – from 60 percent in 1980 to 56 per cent in 1996).

Since 1990, some 10 million more children go to school every year, which is nearly double the 1980-90 average.

East Asia, the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean are close to achieving universal primary education.

The number of out-of-school children decreased from 127 million in 1990 to 113 million in 1998. In Latin America and the Caribbean, for example, the number of out-of-school children was halved, from 11.4 million in 1990 to 4.8 million in 1998. (There are significant gender differences, however. Girls represent 60 per cent of out of school children. In a similar fashion attendance tends to be lower in rural areas).

The number of children in pre-school education has risen by 5 per cent in the past decade. Some 104 million children were enrolled in pre-primary establishments in 1998.

The number of literate adults doubled from 1970 to 1998 from 1.5 billion to 3.3 billion. Today, 85 per cent of all men and 74 per cent of all women can read and write. (NB this uses a fairly limited measure)

Some 87 per cent of young adults (15-24 years olds) are literate worldwide

Despite progress in actual numbers, illiteracy rates remain too high: at least 875 million adults remain illiterate, of which 63.8 per cent are women – exactly the same proportion as 10 years ago. United Nations Briefing – education

Given the scale of indebtedness and the lack of internal funds for education and social programmes, Southern countries have become particularly dependent on assessments and perspectives made by key international and national agencies in the north. Here the various reviews and policy analyses undertaken or sponsored by the World Bank have been particularly influential. As King (1991) argued, the agency map of educational priorities became much more clearly profiled, but this often happened without a corresponding local attempt to analyze national educational requirements. The sheer comprehensiveness of the Bank’s analysis of national education systems, and indeed the thoroughness of many of the education missions of other agencies, can sometimes suggest that there is nothing more for the local agencies to say. This is an exaggeration, of course, but it points to an imbalance between the weight of the external analysis of a country’s educational needs and the country’s own diagnosis. On some debates about education, the signals broadcast from the agency perspective are so powerful it is difficult to hear the local voices at all.

The problem is that the views of the Bank are borne of a particular perspective and their views on economies and on the education sector are open to considerable debate. The Bank’s research insights and opinions are not ordinary research findings but are one significant part of a series of conditions and negotiations about loans to education in the South. Second, there is frustration at the sheer visibility and influence of the polices. Third, there is much indignation that the major Bank polices in education seem to rest so heavily on the work of foreign, Northern scholars and agency staff. The pervasive influence is relatively recent and borne of the economic crisis facing many Southern countries. One reason for the power of the Bank in this area is because their reports are easily available, cheap and well presented. This in a situation where there is relative little literature which looks across a continent or region.

The question of colonialism

Discussion of the dominance of external visions of education inevitably brings us to questions of colonialism and imperialism. Colonialism in its most traditional sense involves the gaining of control over particular geographical areas and is usually associated with the with the exploitation of various areas in the world by European powers from about 1500 on. It is often used interchangeably with ‘imperialism’. (Imperialism – as the extension of state power and dominion either by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas – of course, has a longer history). Colonialism commonly involves the settlement of the controlling (often western) population in a territory; and the exploitation of local economic resources for metropolitan use. It has taken many forms ranging from models of assimilation e.g. France and Portugal where the occupying power has sought make the colony more formally part of their system and culture; to more segregational approaches such as that adopted by Britain.

Neo-colonialism is usually taken as referring to the economic situation of former colonies post-independence. Here the basic argument runs something like the following. Political de-colonization did little or nothing to alter the economic balance between states and the power of western (and now eastern) capital. International law, institutions such as the World Bank (and banks in general), corporate property rights and the operation of world markets has left control in the hands of the elites in the former metropolitan powers.

Under neo-colonialism, as under direct colonial rule, the relationship between the centre and the periphery… is said to involve the export of capital from the former to the latter; a reliance on Western manufactured goods and services which thwarts indigenous development efforts; further deterioration in the terms of trade for the newly independent countries; and a continuation of the process of cultural Westernization which guarantee the West’s market outlets elsewhere in the world. the operations of transnational corporations in the Third World are seen as the principal agents of contemporary neo-colonialism since these are seen as exploiting local resources and influencing international trade and national governments to their own advantage. (Marshall et al 1994: 332)

The linkage of economic change and education; and the interest of the World Bank in such developments would appear to support the thesis that education initiatives can be the agent of colonialism. This is certainly the case for schools, argues Carnoy:

… schools are colonialistic in that they attempt to impose economic and political relationships in the society especially on those children who gain least (or lose most) from those relationships. Schools demand the most passive response from those groups in society who are the most oppressed by the economic and political system, and allow the most active participation and learning from those who are least likely to want change. While this is logical in preserving the status quo, it is also a means of colonializing children to accept unsatisfactory roles. In its colonialistic characterization, schooling helps develop colonizer-colonized relationships between individuals and between groups in society. It formalizes these relationships, giving them a logic that makes reasonable the unreasonable. (Carnoy 1974: 19)

This echoes the sorts of arguments put forward by Gandhi and Kenyatta with regard to schooling. It is also in this way that Freire characterizes colonialism as the culture of silence. The colonial element in schooling (or in informal and non-formal education initiatives) being the attempt to silence particular ways of speaking about the world. To this extent one class or group could be said to colonize another. Sometimes the term domestic or internal colonialism is used to describe such exploitative relationships between the ‘centre’ (the metropolis) and the ‘periphery’ (the satellite) of particular societies or nation states. There have been problems around such usage – especially as colonialism has tended to be used in relation to the exploitation of majority populations by minority groups. However, as a metaphor it remains a highly suggestive one – especially as it dramatizes the links with imperial powers.

As well as direct economic and political arrangements, colonialism also involves powerful cultural forces, in particular, language. Fanon (1952) has written graphically of the experience of being colonized by language. To speak . . . means above all to assume a culture, to support the weight of a civilization” (1952: 17-18). An especially pernicious aspect of this is the way in which this entails taking on a restricting and demeaning sense of self. One of Fanon’s main targets was the extent to which ‘blackness’ in French (or English for that matter) was associated with sin and evil.

In an attempt to escape the association of blackness with evil, the black man dons a white mask, or thinks of himself as a universal subject equally participating in a society that advocates an equality supposedly abstracted from personal appearance. Cultural values are internalized, or “epidermalized” into consciousness, creating a fundamental disjuncture between the black man’s consciousness and his body. Under these conditions, the black man is necessarily alienated from himself. (Poulos 1996)

With the work of Said (1985), Spivak (1990) and others we now have a powerful set of understandings concerning the discourses of colonialism and the way in which it is imposed upon institutions and draws people into its net. (This body of literature is sometimes, confusingly, described as post-colonial theory. The ‘post’ here can be variously taken as a historical period after colonialism; as being concerned with those writers who opposed, and hence looked beyond, colonialism; and as somehow linked with the discourse of post-modernism or post-modernity – see Childs and Williams 1997 for a discussion and review). Education systems, in their different forms, are key carriers and promoters of the discourses of colonialism. They are also potentially significant weapons in the countering of such discourses.

Non-formal and informal education programmes

Many of the adult (and non-formal) education programmes associated with ‘post-independence’ governments looked to combat ‘colonial mentalities’ and to further a commitment to the emerging nation state. (See Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, for example, or Steele and Taylor’s discussion of Indian adult education programmes). Another overt example of an anti-colonialist programme was Cuba’s Schools in the Countryside initiative which had as one of its objectives, ‘to eliminate economic, political and cultural dependence on the United States’ (quoted in Simkins 1977: 49). Certainly, as writers such as Fordham (1993) have shown, non-formal education initiatives became associated with work that was self-consciously ‘relevant’ to the needs of disadvantaged groups. A number of those involved as educators were concerned with reducing poverty, increasing equity and about greater equality in the distribution of power and resources, but were constrained by political circumstance.

[E]ducation is not politically neutral. It is an active supporter and faithful reflector of the status quo in society. If the status quo is predominantly unequal and unjust, and it is increasingly so, education will be increasingly unequal and unjust and there will be no place for non-formal education to improve the conditions of the poor. If, however, society is moving in an equalitarian direction, then non-formal education can and will flourish. (Adiseshiah in Fordham 1980: 21)

Torres (1990:129) in his study of the politics of non-formal education in Latin America similarly argues that many popular education programmes have had a clear emphasis on social mobilization and political development. Churches, unions and groups within social movements have been involved in such initiatives – and there has, in some at least, been a concern to resist unwarranted state intervention into civic life.

However, not all informal and non-formal educational initiatives have been so focused on social and political justice. Indeed, it could be said that many have been rather more concerned with creating conditions for capitalist advancement. Often this has been wrapped up with a desire to stimulate economic growth and development (see adult education and lifelong learning – a view from the south), but it can end up either advantaging investors (frequently from the former colonial powers) or having little impact on growth. The case of literacy programmes is instructive in this respect.

Literacy programmes

Literacy has become associated in the minds of some policy makers with development. Here I do not need to go into debates about functional literacy and absolute literacy. However, we do need to recognize that during the 1980s and 1990s, political conflicts as much as economic problems have sharpened awareness of the issues in non-formal education. Literacy is seen as a political issue by many governments. High illiteracy figures are often regarded as revealing failures in their education systems. Governments of all political persuasions have, therefore, made at least sporadic efforts to promote literacy among adults, sometimes with substantial funding from international organizations. They frequently made significant use of non-formal programmes. In the 1970s there was a fairly widespread belief that literacy was a sound economic investment which would lead to increased productivity. In the recessionary climate of the 1980s, the short-term returns on literacy were called into question, and generally speaking the long-term rewards of education received less attention. Furthermore, with high levels of unemployment, there are usually sufficient literate candidates for the shrinking numbers of jobs requiring literacy.

What is more, the outcomes of government-sponsored literacy programmes and campaigns have been extremely mixed. Literacy work has largely taken two forms. Short campaigns involving mass mobilization have been one method. Literacy programmes involving ongoing work over a period years, either nationally or targeting selected communities or regions, have been the other. In societies undergoing major political change, ‘revolutionary governments’ have been generally more able to mobilize people both to teach and to learn. In countries where there is little popular identification with the regime, especially under authoritarian governments, efforts at literacy promotion may be regarded with suspicion or even contempt. It is in these circumstances that non-governmental literacy initiatives have become a focus of interest. It could be argued that greater community involvement and organization may generate challenges to the government – demands for democracy, land reform, and greater access to services such as education. However, one of the key outcomes of such literacy programmes, Youngman (2000) argues, is that they, and the aid that sustains them, work to legitimate capitalist development and social inequality.

Youngman’s study of the National Literacy Programme in Botswana (1978-1987) argued that it was promoted by the state in terms of the modernization of society and the extension of educational opportunity. Aid providers were attracted by its concern with equity.

However…, the programme in fact served to reproduce the class, gender and ethnic inequalities within society. Furthermore, at the political level it constituted a strategy of state legitimation by demonstrating a welfare concern for providing the rural areas with social services. Ideologically, the programme planners in 1979 adopted a narrow and conservative conception of literacy, and consciously reject conscientization or mobilization approaches that might have empowered the learners: ‘the political element in the [Freire] method was not seen as being appropriate to Botswana. There was also a negative response to a somewhat militant campaign’ (Townsend-Cole 1988: 41). The overall consequences of the National Literacy Programme, and therefore of the aid which sustained it, was to legitimate Botswana’s capitalist development and social inequality (Youngman 2000: 135-6)

King (1991) in his excellent survey of the area draws out three key further trends around literacy in the South

A move from a concern with literacy alone to a concern with the schooling-literacy interrelationship. In some of the literature there has been an assumption that as people become more literate they will encourage their children to go to school. There has been little or no research done of this – and indeed the reverse process may be more relevant. What has been of particular concern to the World Bank and others was that the ability of primary schooling to attract and hold its clienteles was faltering. For as long as primary school enrolments were rising as a percentage of the population then it was possible to believe that over the course of a generation illiteracy would been eliminated. In Africa there is now evidence of declining participation in schooling (this may be one of the impacts of droughts, economic disruption and wars). A further factor in some places has been the levying of fees as the income from taxes and aid has decreased. There have also been worries around the quality of primary schooling in a number of states – particularly those that are poor. Lacking textbooks, adequate facilities and teachers the idea of a full primary education is rather remote.

The reassertion of achievable measures of school and adult literacy. In looking at the achievements of both primary schooling and literacy work a basic question is posed: what is the level of basic education for all, including adults, that should be set as a minimum in order to retain elementary literacy skills? There has been an increased interest in the setting of standard measures of performance and here the World Bank has been active. This shift along with the others is sometimes referred to as the ‘new realism’.

A move from the campaign literature to the analysis of literacy realities. This is evident in the third of our trends. There are still very few detailed and textured studies of work in particular countries or regions. There does seem to have been a shift in the literature however, to more grounded discussions of literacy – and less of the rhetorical, exhortorary material.

Street (2001) has assembled a collection of case studies of more recent literacy initiatives which underline a number of the above concerns and that reveal some of the issues around the discourse of non-formal education and literacy.

Conclusion: informal and non-formal education and development

The conclusion must inevitably be that while some informal, non-formal and popular education programmes have had a concern to combat colonialism and ‘colonial mentalities’ others have effectively worked in the opposite direction. The particular power of non-formal education (and things like community schooling) in this respect isn’t just the content of the programme, but also the extent to which it draws into state and non-governmental bodies various institutions and practices that were previously separate from them; and perhaps resistant to the state and schooling. The state often has a significant influence in these organizations – often through the nature of the funding it provides. International aid has a similar impact. Community groups may become part of state education and welfare systems and various activities can become part of school and institutional life. By wrapping up activities in the mantle of community there is a sleight of hand. By drawing more and more people into the professional educator’s net there is the danger a growing annexation of various areas of life (a particular them of Illich’s work). Under this guise concerns such as skilling and the quietening of populations can take place.

Further reading and references

Bhabha, H. K. (1994) The Location of Culture, London: Routledge. Series of essays that focus on post-colonial identity. Develops a theory of cultural hybridity and the ‘translation’ of social difference.

Childs, P. and Williams, P. (1996) An Introduction to Post-Colonial Theory, London: Prentice Hall. Overview of key theorists such as Fanon, Said, Bhabha and Spivak. Written from a literary theory perspective – but useful all the same.

Carnoy, M. (1974) Education as Cultural Imperialism, New York : David McKay. Important exploration of schooling as a means of subjugating people to the interests of the powerful. Develops a theoretical framework that is applicable to education generally.

Foley, G. (1999) Learning in Social Action. A contribution to understanding informal education, Leicester: NIACE/London: Zed Books. Explores the significance of the incidental learning that can take place when people are involved in community groups, social struggles and political activity. Foley uses case studies from Australia, Brazil, Zimbabwe and the USA that reflect a range of activities. Chapters on ideology, discourse and learning; learning in a green campaign; the neighbourhood house; learning in Brazilian women’s organizations; and political learning and education in the Zimbabwean liberation struggle.

Fanon, F. (1952) Black Skin, White Mask (1986 edn. with a foreword by H. Bhabha), London: Pluto Press. Path-breaking study of colonial depersonalization. Examines cultural and ideological processes that create a desire for acceptance and assimilation – and that make for trauma and self-alienation. See, also, (1961) The Wretched of the Earth, London: Penguin. on the economic and psychological impact of imperialism and points of resistance and change.

Gandhi, M. K. (1997) Hind Swaraj and other writings, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 208 + lxxv pages. Text of the 1910 edition of ‘Indian Home Rule’ which looked at the complex relationships between the commercial and governmental interests of the metropolitan power (in this case Britain) and the culture, and social and political organization of the colonized – ‘It is truer to say that we gave India to the English than India was lost’. As well as historical material, the book also includes chapters on education, passive resistance and machinery.

Graham-Brown, S. (1991) Education in the Developing World. Conflict and crisis, London: Longman. 332 + xx pages. Not just concerned with adults, this book provides a good overview of the context for educational policy formation; the nature of provision and explorations of learning and teaching in marginal communities; organizing for literacy; and the future of education in the South.

Green, A. (1997) Education, Globalization and the Nation State, London: Macmillan. 206 pages. A development of Green’s influential earlier work Education and State Formation (1990), this book offers a useful exploration of the impact of globalization on education systems. He begins with a refreshing and necessary critique of postmodernism and then moves on to explore education and state formation in Europe and Asia; technical education and state formation; vocational education; education and cultural identity in the UK; educational achievement in centralized and decentralized systems; and education, globalization and the nation state.

King, K. (1991) Aid and Education in the Developing World, Harlow: Longman. 286 + xviii pages. Examines the effectiveness of donor agencies in a number of different educational policy areas – including literacy and non-formal education.

Memmi, A. (1965) The Colonizer and the Colonized, London: Souvenir Press. A classic study of oppression in colonial settings.

Moore-Gilbert, B. (1997) Postcolonial Theory. Contexts, practices, politics, London: Verso. 243 pages. Good survey of post colonial theory and the challenges to it. Looks in detail at the work of Spivak, Said and Bhabha – the criticisms they have faced and the arguments they have put forward. Two final chapters examine the postcolonial criticism and postcolonial theory; and how postcolonial analysis can be connected with different histories of oppression.

Said, E. W. (1985) Orientalism, London: Penguin. Brilliant critique of western attitudes to ‘the east’ which problematizes many ‘taken-for-granted’ notions. How are we to approach other cultures? From what perspective do we make judgements? See, also Said’s (1993) Culture and Imperialism, London: Chatto and Windus (also Penguin) – series of essays exploring the relationship between culture and imperialism.

Spivak, G. I. (1990) The Post-Colonial Critic: Interviews, strategies, dialogues (ed. S. Harasym), London: Routledge. Important collection of Spivak’s writings etc.

Steele, T. and Taylor, R. (1995) Learning Independence. A political outline of Indian adult education, Leicester: National Institute of Adult Continuing Education. 151 + vii pages. Fascinating overview of programmes and changes in Indian adult education since the 1940s that looks to a political analysis of its role. Chapters examine the English studies and subaltern histories; education in British India from the early years to independence; Gandhi and the dialectic of modernity; education and social development in India from 1947 to 1964: Nehru and Congress; social education and the dream of nationhood; the non-formal revolution and the National Adult Education Programme; Post NAEP – radical populism and the new social movements; and towards a transformative pedagogy.

Street, B. (2001) Literacy and Development, London: Routledge. 240 pages. A collection of case studies of literacy projects around the world. The everyday uses and meanings of literacy and of the literacy programmes that have been developed to enhance them are examined. It includes chapters on Women’s literacy in Pakistan, Ghana, and Rural Mali, literacy in village Iran, and an “Older Peoples” Literacy Project.

Thompson, A. R. (1981) Education and Development in Africa, London: Macmillan. 358 + viii pages. Excellent overview of African education practice that is particularly strong on non-formal education. Chapters examine social change and development; education and schooling; politics and education; economics and education; problems in educational planning; problems of educational innovation; the management of educational reform; non-formal education; re-schooling; and linking formal and non-formal education.

Torres, C. A. (1990) The Politics of Nonformal Education in Latin America, New York: Praeger. 204 pages. Torres explores the literacy programs in several Latin American countries–including Mexico, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Grenada–as the prime examples of adult educational reform. He examines such issues as: Why are given educational policies created? How are they constructed, planned, and implemented? Who are the most relevant actors in their formulation and operationalization? What are the implications of such policies for both clients and the broader society? What are the fundamental, systematic, and organizational processes involved?

Youngman, F. (2000) The Political Economy of Adult Education, London: Zed Books. 270 pages. Useful exploration of adult education and development theory, social inequality and imperialism and aid in adult education.

References

Allen, T. and Thomas, A. (eds.) (1992) Poverty and Development in the 1990s, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Draper, J. (ed.) (1998) Africa Adult Education. Chronologies in Commonwealth countries, , Leicester: NIACE.

Fordham, P. (ed.) (1980) Participation, Learning and Change, London, Commonwealth Secretariat.

Fordham, P. E. (1993) ‘Informal, non-formal and formal education programmes’ in YMCA George Williams College ICE301 Lifelong Learning Unit 2, London: YMCA George Williams College.

George, S. (1989) A Fate Worse than Debt, London: Penguin.

Marshall et al 1994

Poulos, J. (1996) Frantz Fanon, http://www.emory.edu/ENGLISH/Bahri/Fanon.html, accessed 16/02/2001.

Simkins, T. (1977) Non-Formal Education and Development. Some critical issues, Manchester: Department of Adult and Higher Education, University of Manchester.

Strange, S. (1998) ‘The new world of debt’, New Left Review 230: 91-114.

Street, J. C. and Street, B. (1991) ‘The schooling of literacy’ in D. Barton and R. Ivanic (eds.) Writing in the Community, London: Sage.

Townsend-Cole, E. K. (1988) Let the People Learn, Manchester: University of Manchester Department of Adult Education.

Links

Cyberschoolbus. Interactive educational materials, including InfoNation – statistical data for the Member States of the United Nations. (In English, French, Spanish and Russian) from the UN Global Teaching and Learning Project.

Jubilee 2000 Coalition/Jubilee Plus. News and analysis from the campaign to eliminate the cancellation of the poorest countries’ debts.

oneworld.net: news, special reports and campaigns.

UNESCO World Education Indicators: download in Excel format up to date statistics on schooling, literacy etc.

UNICEF Publications Online: Includes the latest version of The State of the World’s Children: Maps showing educational divides; rich world, poor world.

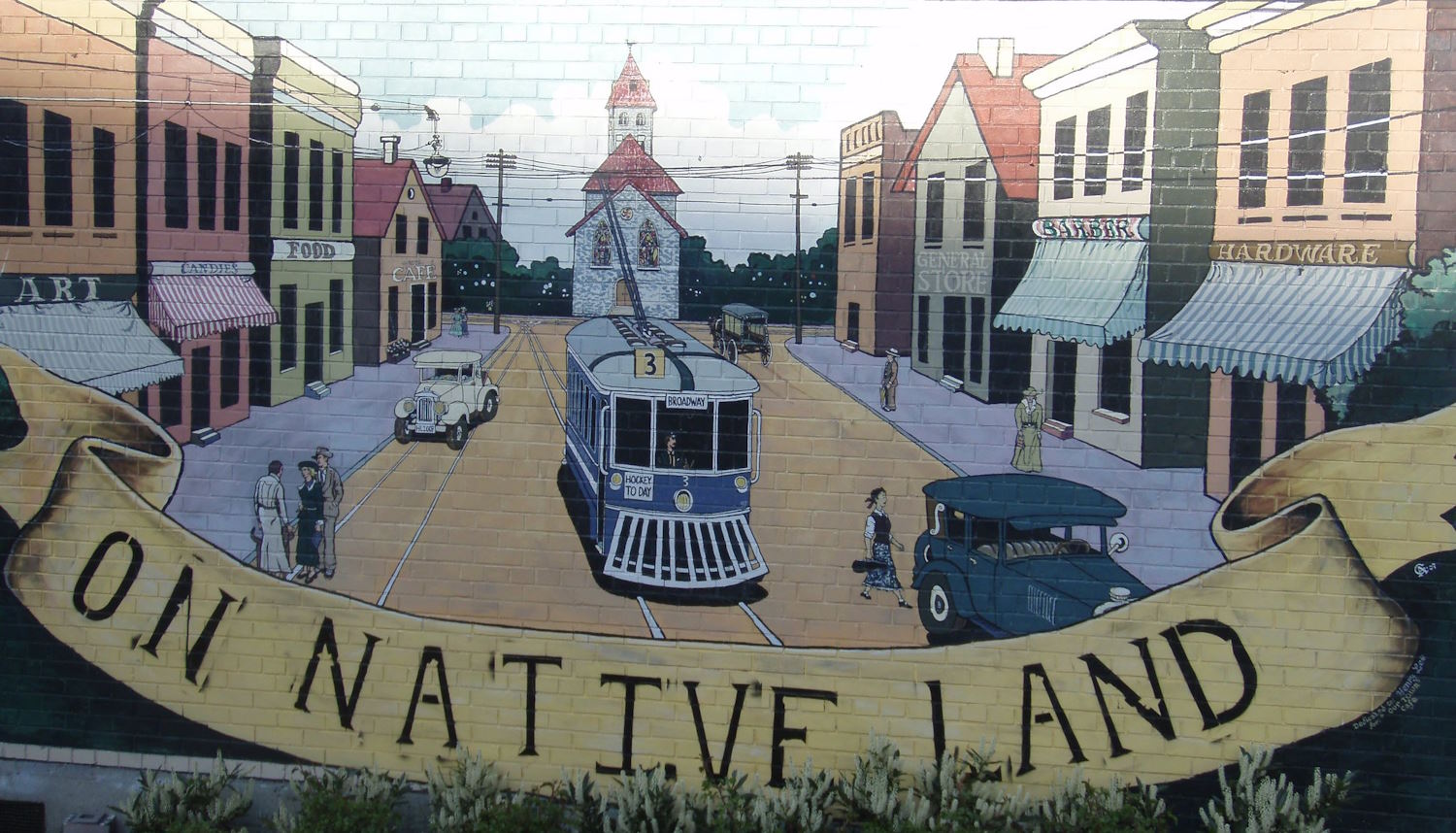

Acknowledgements: Picture: Re-appropriation by Shallom Johnson. Reproduce under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic licence. http://www.flickr.com/photos/shallom/2468981285/

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2001). ‘Informal and non-formal education, colonialism and development’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [http://infed.org/biblio/colonialism.htm].