Carole Pugh raises questions about evangelical approaches to youth work and argues for informal education practice.

contents: emerging themes · motivation · purpose · conversion as purpose · a broader approach · christian relational care · spiritual development · an informal education approach · case studies · conclusions · references · acknowledgements ·how to cite this piece

Christianity played an important role in the development of work with young people from the work of Raikes in the Sunday school movement, through the Victorian era to the inception of the statutory youth service in 1939.

Emerging themes

Hannah More perhaps the first documented youth worker undertook a programme of elementary education, religious instruction, industrial and domestic training, and social welfare in the 1790’s. She openly proclaimed her supreme aim of making Christians; rather than challenging the established order. She saw her Christian duty embracing both evangelism and social action (Jones 1968, Collingwood & Collingwood 1990). This brought More into conflict with a village curate, for undertaking educative work that challenged the established authority of the church and local farmers. Her desire for action was unacceptable to some religious organisations. This initial tension continues unbroken throughout the history of Christian youth work. For while some insist evangelism is the primary aim, others perceive a broader role, placing social action alongside conversion. For example ‘Robertson of Brighton’ formed the Brighton Working Man’s Institute, against prevailing evangelical sentiments, for recreational and cultural education. He advocated a social gospel, believing that failing to tackle social issues led to working people focusing on social action and rejecting religion (Eager 1953).

Tensions also existed between evangelism and Christian Socialism. Dolling, established St. Martin’s mission which was a practical amalgamation of social life inspired by religion, a ‘club-cum-chapel’ but was forced to resign after allowing Socialist politics to be preached (Eager 1953: 217).

The YMCA quickly recognised that it could not limit its membership to young professional Christians, or it’s content to purely devotional activities. Its aims from early on included mental improvement, and it allowed non-Christians as associate members (Binfield 1973). Seeing Christian discipleship relating to the whole of life, religious, educational, social and physical. The outworking of these principles have proved complex.

The Girls Friendly Society aimed to prevent girls from ‘falling’, setting standards of purity for each member to maintain (Heath-Stubbs 1926: 4). While working towards change, initiating the registration of domestic employment, for example, it focused on promoting Christian character. The YWCA recognised no division between the secular and the sacred and aimed to meet the physical, mental, social and religious needs of young women.

The emergence of the Boys Brigade and Scouting movements revealed similar tensions. Smith, the founder of the Boys Brigade, embraced the evangelical tradition and consequently the movement had a religious motive and purpose, with each company being associated with a Christian church (Eager 1953: 320). Baden-Powell on the other hand rejected evangelical revivalism. He refused to bind the Scouting movement to one institutional religion.

Circular 1486, which in 1939 presaged serious state involvement in youth work, stimulated some churches into action. The Methodist Association of Youth Clubs was formed to promote standards and use Christian evangelism within club work. The MAYC however has been criticised for, on the one hand becoming too involved with the secular youth service resulting in a weakening of the evangelical message, on the other for being too church minded and failing to serve the unattached (Hubery 1963).

State involvement in the provision of youth work raised further debates. While Albemarle pays tribute to those ‘whose strong ethical feelings’ motivate them to undertake the work it questions their appropriateness (HMSO 1960: 38). The importance of spiritual and moral development and the ‘Communication of Christian values’ were still recognised. However, it was felt that these principles should be introduced by example rather than through assertion (HMSO 1960: 39). There was concern that the youth service should not be a disguised backdoor to religious belief. Three forms of youth clubs were identified; the closed club, for church members only; the interdenominational club, in which religion still plays some part; and clubs in which there is no obvious religious observance (Brew 1943). The debate post-1940 was no longer over evangelism or social action as the appropriate expression of Christianity. The place of Christianity in youth clubs had itself been questioned. Practice was now broader ranging from secular provision to overt evangelical approaches. (See fig. 1)

Figure. 1. Themes in youth work practice

|

Youth work with no spiritual content. |

Youth work with a spiritual but not necessarily Christian content. |

Youth work based on Christian principles focusing on a social action approach. |

Christian youth work adopting an evangelical approach. |

However, this is not an either-or dichotomy, as members, workers and situations change so the balance may shift. Even for example within a residential week the different sessions and interactions can be placed in different places between the polarities. The pull between them creates a constant tension within Christian youth work that can flare up at any time, may simmer and simply blend into everyday practices or may be denied.

The debate between the application of Christian evangelism or a broader view of Christian social action to youth work revolves around beliefs, consequently, there can be no solution as both sides, in their view, hold equally valid positions, which ultimately rest on statements of faith rather than proof. Certain practices have been questioned by reference to both the principles of the faith and of youth work. In a democratic society, it is wrong to prevent the expression beliefs, however, I believe that it would be beneficial for youth work and young people if certain methods and purposes were defined as outside the boundaries of youth work and informal education.

Motivation

Barnett (1951) argues that Christian youth work is and should remain different from ‘secular’ youth work, that it is a sacred Christian duty to meet the spiritual needs of young people. Faith sets Christian and non-Christian workers apart providing a unique motivation for Christian workers.

Central to Christian youth work is a sense of vocation, a calling or invitation from God to engage in young people’s lives. God is sighted as the sustenance, guidance and inspiration for their work. Christian care for young people is based on the value each individual has as an ‘object of God’s redeeming love’ (Warner 1942:45). The Christian youth worker is seen as a servant of the kingdom of God rather than of a political or social agenda.

While the motivation of Christian workers has been examined, there has been less of a focus on non-religious motives although they must exist and play a vital role in youth work. Secular workers’ motivation derived from their life philosophy may not be examined for varying reasons, possibly because of a lack of opportunity to do this during training (Jeffs & Smith 1990). Christian youth work practice provides many situations where workers contemplate their faith; this consideration of life philosophy is not built into secular youth work practice.

This motivation sets Christian youth work apart, as it is based on beliefs, which to non-Christians may seem unfounded. While the concerns around social justice may appear the same, the agenda is different (Ward 1997). Motivation alone does not explain the differing approaches, it is dependant on the individuals’ beliefs about the primary purpose of their work.

Purpose

Debate over the purpose of youth work is ongoing; based around notions of the ‘good’ and ‘human flourishing’ definitions of which remain open for discussion (Jeffs & Smith 1990). Ward (1997) argues that ‘youth work’ never applied solely to secular settings. Christians have used the term to describe their work with young people including ‘evangelism and Christian nurture’ alongside the principles and values advocated by secular youth work (1997: 3).

Christian youth work has varying purposes, encompassing different approaches. The particular purpose a Christian worker seeks will have implications for the methods and content of their work. Influencing their choice of a structured, semi-structured or unstructured approach (Breen 1993, Ward 1995).

The models that follow are simplified often clear distinctions between approaches are obscured. However, their construction based on broad trends is useful for a theoretical consideration of varying approaches.

Conversion as purpose

Christian youth work is often accused of being pre-occupied with the conversion, rather than building self-reliance and maturity (Milson 1963). Should it seek conversion or take a broader view of ministry, embracing social action to benefit local communities as well as preaching (Sainsbury 1970)? The Christian community holds no consensus on the relationship between evangelism and youth work (Ellis 1998).

Where conversion is the purpose, Christian’s ‘are involved in youth work for no other reason than to tell the gospel story’ (Ward 1997:27). Or as Ashton and Moon explain

Christ does not teach us to support the personal development of young people so that they may realise their full potential. We are instead to call them to repentance and faith, because only in that way can they realise their full potential.(1995: 27)

Accordingly, success constitutes large numbers of young people making ‘decisions’ for Christ (Ellis 1998: 10).

This approach has been criticised as constituting the sweetening of an ‘ideological pill’ using by social and recreational activities (Milson 1963: 124). The evangelist seems unwilling to allow young people to work out their own problems, rather seeking conformity to a previously accepted theological pattern. The evangelist must always be a propagandist rather than an educator, seeking ‘inculcation of a creed’ and not ‘the enrichment of a person’ (op cit: 124). This approach has been criticised for promoting middle-class morality and narrowing the programme because of its preoccupation with spiritual issues. The content of Evangelical youth work will differ, focusing on bible study, prayer and evangelism alongside social activities (Farley 1998). But it has been criticised for over-simplifying the needs of young people, seeing only spiritual and not social ones (Milson 1963).

This approach often adopts a formal, or closed, style of work. Ward (1997) identifies two approaches: the ‘inside out’, working with young people within the church and, the ‘outside-in’ working with those outside it. The ‘inside out’ uses authoritarian methods based on a formal programme. Allowing less exploration by young people; instead of having clearly defined behavioural expectations. Fowler (1981) identified four distinct stages of faith. Stage three fits well within this method. At this time the views of peers and leaders are significant. Young people may be ‘embedded in their faith, unready to reflect on their personal beliefs, instead, deriving these from the group. Movement to the next stage where the individual can separate themselves from the group and decide what they believe requires space for the conscious examination of beliefs (Astley 1995). All are useful, the educator should not rush young people through them, although always mindful of extending development, this approach however seems to discouraged movement beyond stage three (Astley & Wills 1999).

Evangelical youth work has also been criticised for tending to over-simplify; offering single explanations for complex realities. Substituting enthusiasm and inspiration for critical analysis and reflection (Holloway in Ward 1996). This can be linked to its intolerance of the possibility that other views may be valid expressions of Christian faith or the ‘good’. Tendencies that can lead to the breeding of authoritarian rather than democratic leadership styles.

Ward (1996) argues that the evangelical movement reveals a desire to control young people. Following an agenda set by parents to keep Christian children ‘safe’ within the faith, away from ‘threatening’ modern youth culture. Youth work then becomes something done to young people, rather then something they participate in, fostering dependency rather than independence. Encouraging a fear of the secular world so the church youth group becomes an escape from, rather than an engagement in, the world (op cit: 19).

Evangelical youth workers have been seen as ‘indoctrinators’ and ‘brain washers’ whose obsession with conversion reduces their interest in developing self reliance and maturity, eyes are clouded by ideology they see young people as ‘spiritual scalps’ (Milson 1963: 27). Ellis (1998) claims Christ always sought to maintain an individual’s autonomy and would oppose such coercion. This claim is unresolvable, who can know which side God takes, each rely on interpretations of Christianity. Examining the accusation of indoctrination may be more helpful.

Indoctrination is the intentional inculcation of unshakeable beliefs. It seeks to stop growth, and restrict the young persons’ ability to function autonomously. Theissen (1993) argues that Christian evangelism and nurture do not seek autonomous individuals who may then reject the faith. Autonomy requires decisions based on knowledge, the ability to reflect critically on beliefs; often the biased presentation of information prevents this. Doubt and questioning are seen as negative, as drawing young people away from God (Ball 1995). Belief in the evangelical tradition demands ‘absolute acceptance and unquestioning obedience’ to God (Peshin quoted in Theissen 1993: 122). This precludes dialogue and critical analysis.

However, education can never be neutral it is ‘incorrigibly normative’ (Smith 1988: 117 also Hollins 1964). Informal education is built on certain values and ideas of ‘the good’; a belief in democracy and dialogue; a respect for persons; and a commitment to fairness and equality and critical thinking (Jeffs & Smith 1990 & 1996). If Christian youth work is not inherently contrary to these then a Christian interpretation ‘the good’ is not problematic. The problem arises where dialogue proves difficult because Christians recognise that theirs is the only truth. The application of critical analysis to beliefs can prove problematic, as faith demands an unshakeable commitment, even when this appears irrational.

A Broader approach?

This does not mean it is inappropriate to present the Christian message. Hubery (1963: 63) asserts that while there is no room in youth work for ‘dogmatism or narrow-minded indoctrination’ there is for ‘guides, philosophers and friends’ who show ‘a way of life that is religious in its truest sense.’

A distinction can be drawn between ‘inculcators’ and ‘facilitators’ (Barnes in Barnett 1951). Inculcators are thoroughly convinced by a set of principles and their associated code of behaviour and seek to impress these. Education becomes an acceptance of dogma not a voyage of discovery. Facilitators create climates for growth and debate. These two positions present problems for Christian youth work. Inculcation is not acceptable in youth work, but a Christian worker holds a firm belief position, which faith demands should be passed on. This does not have to take the form of inculcation. If the Christian faith is reasonable and equally valid to other belief systems, it is possible to present it while remaining faithful to educative principles (Milson 1963). Providing this is undertaken in an atmosphere where young people are respected and trusted to form their own opinions, where space exists for dialogue. This does not require the worker to become neutral but to open topics for discussion and critical analysis; to be honest and open to challenge; to the possibility that through discussion the beliefs of all may change.

Christian relational care

This is a long term approach and begins by demonstrating God’s ‘care’ for non-Christian young people by building committed relationships with them (Ward 1995). It has a broader definition of Christian mission, aiming towards ‘the good’ while recognising that the worker does not possess the sole definition. This must be worked out through dialogue with young people. However, ‘in the last instance, what is ‘good’ in each circumstance will be defined by reference to Jesus’ (Ward 1995: 36). This approach advocates questioning Christianity without offering ready-made explanations, allowing young people to determine its relevance to their lives (Mayo 1995). It recognises the need to respect people and acknowledges that the Christian definition of good is normative, based on faith.

This differs from the evangelical approach as it respects individuals as they are, not dismissing them as sinful. ‘Extended contact’ follows as the relationship with the group deepens, the worker negotiating to become a leader. ‘Proclamation’, the explicit telling of the gospel, using a more formal approach in a contextualised form, follows and is raised as the primary aim of the work. Young Christians are then nurtured, with the worker acting as resourcer and translator for the group. The ambiguity of this position is recognised;

Trying to leave space for young people to explore the faith for themselves needs to be balanced with some idea of the limits of Christian expression and interpretation (Ward 1997: 63).

Initially, this approach seems to remain faithful to the educational principles of youth work. However, it still contains the possibility for the adoption of an authoritative ‘inside-out’ method (Ward 1997). Telling people the gospel has changed, and the initial nurture work embraces a more exploratory style, but what lies beyond? Is it that Christian nurture is incompatible with dialogue and critical thought? Is Christian nurture different from Christian youth work?

Theissen asserts that ‘autonomous people must be able to reflect critically on their beliefs (this) goes against the aim of Christian nurture’ (1993: 122). This assumes that Christianity cannot survive critical scrutiny, if so, is it a worthy belief? However some believe it is possible to: ‘Toss the whole Christian scheme of things for intellectual examination and practical testing, saying … “Break it if you can” (Milson 1963: 126).

A broader approach recognises the possibility that demonstrating Christ’s care through social action, is an equally valid method of ‘proclaiming’ the gospel (General Synod Board of Education 1996). Christian youth work should not focus exclusively on spiritual issues but embrace social action.

The actions of Jesus often expressed the love of God without requiring any response. It may be inappropriate in many work situations to make explicit links with the claims of Christ. However, faith is an integral part of life. It is inevitable that it will arise in dialogue with young people, and workers should be open about their beliefs and realise the effect this alone may have (Ward 1995, Rosseter 1987).

Spiritual development

Youth work’s development has tended to polarise Christian and secular perspectives. Although ‘spiritual development’ has remained on the secular youth work agenda, there is little evidence of it in practice (Huskins 1996). Recent years have seen a debate concerning spiritual development in the youth service. However, it’s precise meaning is contested. The term encompasses ‘awareness of that which is deepest within us, that which responds to other people and the world around us, that which gives us a direction in life’ (Salmon 1988:10). Christian youth workers could seek ‘spiritual development’, allowing young people to explore ‘what is meant by the term God’ before considering what God to believe in (Cattermole in Dunnell 1993: 62) restoring spirituality to youth work practice, giving young people opportunities to explore what makes them who they are (General Synod Board of Education 1996, Salmon 1988).

However, the usefulness of these developments to the Christian youth work debate has been questioned. For example to what Christians should support concepts of spirituality outside Christianity? (Dunnell 1993). To adopt this approach Christian workers need to accept the equal validity of other spiritual experiences without condemnation; this may prove difficult. For those who can this spiritual development offers a method for approaching spirituality that recognises its importance and opens it to critical reflection.

An informal education approach to Christian youth work?

Informal education is premised on certain values and concerns: the worth of the individual learner; the importance of critical reflection; and the need to examine things that may be taken for granted (Jeffs & Smith 1990). It is a process requiring certain ways of thinking and acting in order to encourage people to engage in the world.

Ellis (1990: 91) argues that Jesus ‘used the principles now enshrined in informal education to great effect’ by creating shared experiences that challenged individuals to rethink their value systems. However informal education in a Christian setting has been seen as largely ineffective in achieving conversion (op cit). The lack of ‘success’ in Christian informal education has been attributed to the gap between Christian and non-Christian worldviews. The proposed solution is the blending of formal and informal methods into an approach that allows the necessary explanation of the Christian position (op cit).

However this assumes it is acceptable to measure success by the production of committed Christians. This may not be applicable. Informal education does not seek specific changes in individuals but has a broader concern with development towards ‘the good’ (Smith 1994). The adoption of an informal education approach entails creating conditions that enable young people to make their own enquires and formulate their own philosophy (Brew 1943). A commitment to dialogue requires openness to the possible truth in what others say, accepting the validity of others belief’s and being willing to reassess Christianity in their light (op cit 19). A commitment to critical enquiry requires a movement away from strongly held opinions, to a place where beliefs can be scrutinised (Abbs 1994). There will always be disagreement over what constitutes ‘the good’; the application of reasoning and critical reflection, however, allows for debate and some degree of agreement. If Christianity has nothing to fear from critical thinking and moral reasoning then it has nothing to fear from the application of the informal education approach. It offers both Christians and non-Christians an invitation to consider their beliefs in the light of others experiences, providing the opportunity for young people to adopt and adapt their own philosophies, rather than inherit the beliefs of others.

Case Studies

These models will now be used to examine the practice of four different Christian youth work agencies.

Methodology. The analysis is based on the examination of materials produced by these agencies. I contacted the agencies, explaining the purpose of my research and asked them to send information including annual reports, training programmes, mission statements, and any material they produced. All four responded, sending varying amounts of information. Where there were gaps I also used Internet sites to gain additional information. I acknowledge that these reports are written with a particular purpose in mind. The content is carefully monitored to present a certain image of the work. The variety of practices and philosophies at the local level may not be represented. However I was interested in the motives, purpose, methods and content of the work of these organisations, the analysis of these reports provided a useful insight into the issues and approaches they regard as appropriate and important. Their chosen presentation of their work reveals something of their values and purpose.

The four agencies were selected to gain a broad view of Christian youth work. Large, high profile organisations were chosen as these represent a large proportion of Christian youth work practice and produce much of the written Christian youth work ‘theory’.

Youth For Christ (YFC). Youth For Christ operates in 120 countries (YFC 1999a). They have 50 British centres (YFC 1999b). British Youth For Christ has responsibility for five creative arts teams who ‘travel around and share the gospel with young people’ (YFC a). They run Operation Gideon and Apprenticeship schemes, which are one, two, or three-year training programmes in ‘evangelism, discipleship and youth work, (YFC b). ‘Street Invaders’ is a three-week training experience in ‘evangelism and social action’ where young people work with evangelists sharing their faith with their peers (YFC c). YFC produces material for Rock Solid clubs run by affiliated churches throughout the country. These are aimed at non-Christian young people. The programme is pre-prepared combining games, group discussions, video clips and role-plays culminating by examining ‘how God wants to help’ (YFC d).

Purpose. YFC’s mission statement commits them to ‘Taking Good News relevantly to every young person in Britain’ (YFC 1997: 8). Their ethos focuses on the declaration of the gospel through contact with ‘thousands of young people a week’ sharing the ‘Good News’ with them (YFC 1997: 4).

Methods. YFC is committed to evangelism comprising: –

Demonstration – The practice of engaging in community development as a means of alleviating material need AND building long term, unconditional relationships with young people demonstrating acceptance and love.

Declaration – Any means of communicating the gospel that invites people to make an informed choice about what has been communicated.

Decision – The point at which a person becomes aware of the need to make this informed choice to follow Christ and does so.

Discipleship – A process by which people follow Jesus and grow in relationship with Him. (YFC 1997: 9)

YFC states its commitment to an ‘incarnational approach’ that demands a ‘relational model’ of working. However ‘a vast amount of the total time and effort of YFC ministry is devoted to schools’ using assemblies and lessons as opportunities to present their message (CRA 1998). This formal method does not fit well within the relational model of youth work outlined by Ward (1995). The focus within YFC is on developing ‘culturally relevant’ methods of communicating the gospel on an occasional basis, rather than adopting a long-term relational approach. Of the five creative art teams, only one focuses on a particular location, and this has a regional remit. While varied methods of communicating the gospel are used the content of the programme itself is narrow, focusing on conversion and nurture.

The work of the centres in running school Christian Unions, Christian youth groups, drama clubs or bands are long-term approaches, focusing more on relationship building. Again a large proportion of this work is undertaken in schools, but a shift away from a teacher and lesson orientated structure towards more informal, relational methods has occurred in some centres (YFC 1997: 10). A more relational approach is seen in the work of Urban Action Manchester. Here the stated purpose is a broader one of enabling marginalised young people to ‘transform their lives’ and ‘reach their full potential’. However, the underlying theme is still conversion rather than social action possibly seeing only spiritual needs and failing to address social issues.

Operation Gideon is a one to three-year programme of ‘top training in evangelism, discipleship and youth work’ beginning with six weeks residential training covering ‘theological issues, evangelism, youth work skills and practice and communication skills’ (YFC b). The remainder of the year involves placements in churches and centres. Second-year students have the option of gaining a part-time youth work qualification. The third is spent as a trainee worker with a view to a permanent position.

This provides young people with the opportunity to practice youth work, however, the omission of a theoretical consideration of the work raises concerns. There is a notable absence of theory drawn from ‘secular’ youth work (YFC 1994). The inclusion of the part-time course in the second year moves towards correcting this, however, the implied possibility of employment following the third year, with much experience, but only limited theoretical knowledge raises concerns. This practice could contribute to Christian youth works ‘lack of a well-articulated and theologically informed body of knowledge’ (Ward 1995). The apprenticeship programme comprises a placement combined with the option to study towards a youth and community work degree from the Centre for Youth Ministry or the basic training scheme for part-time workers run of Brunel University each offer the possibility of a more considered theoretical analysis. However the selection of a Christian rather than secular Youth Work course raises questions. This could reflect the need for Christian workers to have considered theological debates which secular courses do not provide the opportunity to do. It might indicate a desire to protect Christian youth work from the ‘unhelpful’ scrutiny of secular youth work theory (Ward 1996: 73).

YFC explicitly states its purposes as evangelism, conversion and nurture. There are many variations in style and focus between the centres affiliated to the national movement and the teams run more directly by British YFC. There is little mention of participatory practice, or the promotion of autonomy among young people. This raises concerns about the possibility that the work fosters dependence rather than independence. Much of the work undertaken is based on formal education practices and there is little evidence of a commitment to democracy, dialogue or critical thought. The material and training it produced are based on a large quantity of experience, but are not subject to a theoretically informed analysis.

Methodist Association of Youth Clubs (MAYC). The MAYC’s purposes include the promotion of high standards in youth work; the use of ‘the club as a means of Christian evangelism, education and service’; and the co-operation in united Christian action (Barnett 1951: 75). Clubs wishing to join the MAYC were required to provide a balanced programme, ‘facilitating physical, social, mental and spiritual well being’, and to offer opportunities, for members to share in club management, and Christian teaching by ‘invitation rather than compulsion’ (Barnett 1951: 76). Today the MAYC works throughout Britain often operating through supported and trained voluntary workers (MAYC a).

Purpose: MAYC today is ‘about enabling young people to achieve their full potential, in the company of people of faith, by;

Creating an environment where that can happen.

Developing a sense of identity.

Enabling young people to make choices and influence their world.

Making disciples of those who have begun a journey of Christian commitment.

Servicing the network and the whole church. (MAYC a)

This is a broader approach concerned with young people’s development and not only conversion. There is not the same focus on evangelism, in terms of gospel presentation. ‘Most people in the work (with the MAYC) would see it as the churches expression of mission in the widest sense offering young people, and especially the most vulnerable the opportunity to realise their full potential’ (Bagnall 1999 personal communication). The broad nature of this approach, seeking to move towards ‘the good’ and not only conversion, is still seen as problematic, often church members wish to see ‘success’ in terms of increased church attendance (op cit).

Methods: MAYC works in a variety of settings, some are church-based, others have a more ‘secular’ feel. It promotes a number of different activities, performing arts, sport, and discussion groups, avoiding the narrow programme of some Christian youth work. There is a focus on participation by young people, both in planning and running events organised by MAYC and seeking to give young people a voice in the Church (MAYC 1995). There is also a focus on social action. ‘World Action’ forms part of MAYC and is committed to ‘action for change on issues of justice and peace’ encouraging young people to become ‘citizens of today’s world’ by providing ‘opportunities, information, skills, inspiration and affirmation’ for participation in international and local community work (MAYC a). MAYC organises youth exchanges, which provide opportunities for culture to meet culture and faith to meet faith for ‘Through listening and sharing together, lives have been challenged, enriched and changed for ever’ (MAYC a). MAYC is organised democratically; its structures encourage participation and representation by young people in forums such as the Methodist Conference, and the MAYC Executive (op cit). This appears to open the route for a broader consideration of spiritual development and the use of critical reflection. There is a respect for people of other faiths, a prerequisite for dialogue, and a willingness to engage with them (MAYC 1997). MAYC’s volunteer leaders appear valued and the benefits of training and supporting them recognised, although the reports provide no examples of this in practice.

The MAYC adopts a broader approach to Christian ministry thereby maintaining the educative focus of youth work. The MAYC acknowledges the distinction between youth work and youth evangelism and the methods and philosophy adopted apparently leave room both approaches (MAYC a).

Church Pastoral Aid Society. Church Pastoral Aid Society (CPAS) aims to help churches ‘make disciples of Jesus Christ’. The Society was founded in 1836 with the vision of ‘taking the gospel to everyman’s door [sic]’ (CPAS 1999a). They aim to promote evangelism in local churches, support church leadership and youth, children and families through the production of resource material and training for leaders (op cit). CPAS has the largest church-based youth and children’s work in the Anglican Church of the UK and Ireland (CPAS 1999b).

Purpose: CPAS is primarily an evangelistic organisation, promoting evangelism through training and resourcing churches. There was virtually no social action agenda present in their material. Where social issues were raised a very passive approach was advocated, in terms of ‘being aware’, and ‘praying’ and ‘supporting a ministry that deals with them’ (CPAS 1997: 20). There is an underlying theme of keeping Christian young people ‘safe’ in the church, rather than reaching out to the wider community. The approach appears to seek to control young people through the creation of a separate Christian culture.

Method: The CPAS provides training and resources to groups run by local churches. Groups envisioned by CPAS exist primarily for Christian young people, adopting the ‘inside-out’ approach. Success is judged through, ‘evidence of the Bible being studied, faith being shared with friends, participation in church life, willingness to serve and regularity of attendance’ (CPAS 1997: 4). It is seen as vital to challenge young people regularly with the gospel. Young people may choose to leave the group, provision is not made for them outside of a Christian context (op cit).

The materials and ‘tools’ produced focus on practical ‘handbooks’, and advice, useful tips and ‘ready to use sessions’ (CPAS 1998). Few resources had any theoretical considerations and none were from a secular perspective (op cit). The ‘ready to use’ programmes seem to be narrow, focusing on biblical approaches to certain issues. There is little scope for young people to determine these programmes. An authoritarian rather than dialogical approach is encouraged.

This approach seems to pay no regard to the nurturing of self-reliance or maturity in young people; concerning itself solely with producing compliant Christian young people, satisfied by the ready-made doctrine and faith supplied to them. Milson identifies such approaches and accuses them of representing ‘counterfeit Christianity’ (1963: 27). In the worst examples of this approach, this is probably true, at best it could only be viewed as well-intentioned but very poorly informed and considered.

The World Wide Message Tribe/ Project Eden. The World Wide Message Tribe (WWMT) formed in 1991 uses dance music to present Manchester high schools with the Christian message (The Message a). This led to Project Eden, on the Wythenshawe housing estate in Manchester, aiming to move up to 50 young Christians into the area to live out their faith and establish a number of grassroots projects (The Message b).

Purpose: There is a commitment to demonstrating as well as declaring the gospel. The presentation of which in schools using high-energy dance music is combined with a long-term commitment to the area. The establishment of grassroots projects seems to offer promises of social action. However, Christians were moving to Wythenshawe to live alongside young Christians expressing a desire to ‘keep’ as well as ‘reach’ young people rather than to engage in social action (The Message c).

Methods: The WWMT focuses on schools work. Project Eden also works in schools but adopts a more informal relational approach. They have established a creative arts club and undertake detached work reflecting the ‘Relational Youth Work’ model put forward by Ward (1995). Opportunities for dialogue are created where Christianity can be applied to the young persons’ cultural context. Once young people have made a decision to follow Christianity there are discipleship groups for them to attend which use material produced by WWMT as their basis. This package includes written and visual introductions to the Christian message, ‘with exercises to help young Christians grow’ (The Message 1998a). This material addresses issues of social injustice however the application of a more formal approach restricts the possibilities for young people to engage in dialogue and influence the direction of their exploration of Christianity. Christian nurture again raises questions about the creation of dependency rather than independence.

Project Eden, although having no explicit social action agenda has noted an ‘improvement in the physical area’ (The Message 1998b). If workers are to develop relationships and ‘care’ for the young people there must be a concern with broader issues and not only spiritual conversion (Milson 1963). The WWMT and Project Eden represent an interesting combination of formal and informal education. Setting the Christian relational care and informal education approaches against the background of an overtly and formally proclaimed Christian agenda. However, the extent to which young Christians are allowed to work out their own faith raises questions. This approach offers some interesting opportunities but is narrow in its omission of social action. Faith is being demonstrated, but what is it being allowed to change?

Summary. The four agencies examined show differences in purpose, approach, content and emphasis, yet all are contained at present under the title of Christian youth work. This breadth is not necessarily a strength. The reluctance of many Christian organisations to use ‘secular’ theory and critical analysis has left Christian youth work with a weak theory base. Christian youth work training seems to suffer from similar problems focusing on ‘skill development’, rather than a critical analysis of the purpose and methods adopted. Some of the practice analysed revealed tendencies towards inculcation rather than education and critical analysis, toward the creation of dependency rather than independence. However, some practice reveals the hope that Christian youth work can offer young people the opportunity to critically examine their world. Revealing Christianity as a positive, challenging and active philosophy. One which is capable of informing a progressive theory and practice of youth work, that can work constructively towards achieving ‘the good’.

Conclusions

The postmodernist interpretation posed questions to youth work and Christianity. Postmodernism encompasses a distrust of meta-narratives, a recognition of subjectivity, plurality and relativism and a search for spirituality (Bauman 1993; Tomlinson 1995). This encouraged the identification of two approaches to education (Usher & Edwards 1994). The legislative approach, which is rooted in modernity, seeks to determine reality for the majority of people; and an interpretivist orientation.

The postmodernist critique challenged the Christian conception of ‘truth’, by demanding the acceptance of plurality. For evangelicals ‘truth is a very clear-cut issue: something is either true in a fairly literal or historical way or it is not true at all’ (Tomlinson 1995: 87). Thus evangelical youth work adopts a legislative approach, seizing opportunities to define reality. While youth and community work are urged to adopt an interpretivist stance that recognises the role of spirituality amongst many. Evangelical approaches, however, cannot function within this model as they adopt a legislative role, determining spirituality in any broader context as outside Christian youth work.

Training. The examination of practice raised questions about the quality of Christian youth work theory and training. While secular and Christian youth work share similar roots differences are apparent in their practices. The education provided by secular youth work courses shapes the values and practices of their students. Ward proposes that secular youth work has moved away from its Christian heritage and become ‘less and less sympathetic to a committed Christian perspective (Ward 1996: 73). The practice of Christian workers graduating from professional secular training courses and undertaking Christian youth work has been criticised for lacking the desire to save souls. Ward (1997) argues that Christian youth work covers evangelism and Christian nurture alongside the principles and values proposed by secular courses, however combining youth work skills and methods with evangelical concerns and expectations has proved difficult. The evangelical concern with specific results in terms of conversions does not fit well with secular youth work practice (op cit). The ‘unhelpfulness’ of secular youth work theory to evangelical Christian youth work suggests that Christian youth evangelism is different. That it is based on different principles. If this is the case then the term ‘youth evangelism’ may more accurately reflect this different emphasis?

What is it about secular youth work training that makes it unhelpful to evangelical Christian youth work? It seems to rest on the insistence that the plurality of views present in our society is recognised and respected. That young people are trusted to form their own views and that these are respected even when this takes them outside Christianity. If some advocating Christian youth work practice cannot accept this plurality, then how can they operate using dialogue? Can they seek to be educators, not indoctrinators? The critical analysis of beliefs allows for discussions on such topics to reach some kind of agreement. However, a fundamentalist standpoint cannot allow critical analysis.

It seems necessary to acknowledge that some Christian youth evangelism is different from youth work and rejects some of the principles on which youth work is premised. This leaves Christian youth evangelism free to develop its own methods and practises. To provide different training, perhaps still embracing elements of secular youth work theory, but also focusing on theology and missionary practise and acknowledging the difference in the purposes of the work.

Milson (1963) did not believe that secular theories are inherently unhelpful to a broader definition of Christian ministry. He held Christian youth work can remain faithful to educational principles. In this case, secular training should not present insurmountable obstacles to the exploration of youth work practise in light of Christian faith. It may challenge assumptions and leave no easy answers, but is this not the nature of youth work, that, in seeking ‘the good’ there will be no one solution. This challenging can be positive. Offering opportunities to consider the complex debates surrounding the appropriate purpose of Christian and non-Christian youth work through debate, dialogue and critical analysis. The tendency to seek separate Christian courses reflects problems identified within the evangelical tradition. Where ‘safe’ provision for Christians is sought, where the regulation of beliefs restricts questioning, laying the foundations for the situation we have now where Christian youth work practice is not rigorously analysed, critiqued and improved because there is no platform for this discussion.

For those who view the differences between Christian and secular youth work as surmountable the possibility of Christians training and working with non-Christian workers can be explored. I have found nothing in mainstream youth work that is inherently contradictory to Christianity providing Christians are willing to engage in dialogue and critical reflection. The inclusion of an exploration of spiritual development as an aim of youth work on secular courses offers the opportunity for an examination of what this could mean for both Christian and non-Christian practice. Encouraging all students to examine their motives and ask questions about what they believe and how these beliefs may influence their practice. Encouraging Christians to undertake secular courses, rather than establishing separate Christian youth work courses seem to hold many benefits. Placing Christians in a position to influence the development of secular theory and critically examine their own contribution.

Practice. In a heightened climate of dialogue doors are opened for a more integrated approach to practice. Networking Christian and non-Christian organisations provide opportunities for young people to meet and enter into dialogue with those who hold different beliefs in a climate of respect. This would broaden the approach of Christian organisations, and avoid criticisms of an overly narrow programme.

Informal education offers Christian and non-Christian approaches a means to enter dialogue. It is not only concerned ‘with those who are going through a phase of atheism but [also] with those who are going through an emotional hotbed of religious experience’ (Brew 1943: 146). Informal education leaves room for young people to question their own beliefs, rather than promoting the acceptance of a pre-packaged deal. Aiding young people in moving towards the final stage of faith development with beliefs having been examined and ‘consciously adopted’ (Fowler 1981). Trusting young people and allowing them the space to develop from one stage of faith to another.

Conclusion?

It is impossible to form one conclusion. The nature of belief prevents this. I may argue Christian evangelism is not youth work as it is based on different principles. However, it is possible for an evangelical Christian to question the appropriateness of the principles I have cited as underpinning youth work. The argument that it is necessary to accept and respect the plurality of beliefs in the world today in order to achieve dialogue is premised on a belief that no religion is objectively true. This secular humanist belief is dominant today. The acceptance of this as the basis for argument opens criticisms of becoming an ‘evangelist’ for this view (Ellis 1990).

I acknowledge this criticism, but cannot answer it, as again this is ultimately a matter of belief rather than reasoning. The advantage of accepting this stand, however, is that it opens ideas for critical analysis alongside possibilities for dialogue. Although this may never result in one solution it leads the way to communication and mutual respect.

Adopting an informal education approach to practice may mean fewer young people become Christians and those who do have to constantly struggle for answers and live with a faith that in many ways is ambiguous. But I would rather work towards encouraging young people to be ‘honest doubters’ who hold their own autonomous faith, who can and do critique teaching that it put to them than work towards producing converts who are encouraged to accept on authority their beliefs.

References

Abbs, P. (1994) The Educational Imperative: A Defence of Socratic and Aesthetic Learning, The Falmer Press, London.

Astley, J. (1995) Faith Development and Young People. unpublished paper.

Astley, J. & Wills, N. (1999) Adolescent Faith and its Development, Awaiting publication.

Aston, M. & Moon, P. (1995) Christian Youth Work: A Strategy for Youth Leaders, Monarch, Crowborough.

Bagnall, M. (1999) personal communication.

Ball, P. (1995) ‘Growth or Dependency’ in Ward P (1995) Relational Youthwork: Perspectives on Relationships in Youth Ministry, Lynx, Oxford.

Barnett, (1951) The Church Youth Club, Epworth Press, London.

Bauman, Z. (1997) Intimations of Postmodernity. Routledge London.

Binfield, C. (1973) George Williams & the YMCA. Heinemann, London.

Breen, M. (1993) Outside In: Reaching Unchurched Young People Today, Scripture Union, London.

Brew, J. M. (1943) In the Service of Youth, Faber & Faber, London

(CRA) Christian Research Association (1998) ‘Youth For Christ’ in CRA Fact File, No. 5 Summer 1998.

Church Pastoral Aid Society (1999a) http:///www.cpas.org.uk/cpasinfo.htm

Church Pastoral Aid Society (1999b) http:///www.cpas.org..uk/frameyc.htm

Church Pastoral Aid Society (1997) CY, Dec 1997.

Church Pastoral Aid Society (date unknown) Youth and Children, tools you can trust.

Collingwood, J. & Collingwood, M. (1990) Hannah More, Lion Oxford.

Doyle, (1999) Called to be an Informal Educator, in Youth & Policy No.66.

Dunnell,T. (1993) Mission and Young People at Risk 2nd edition, Frontier Youth Trust.

Eager, W. McG (1953) Making Men: The History of Boy’s Clubs and Related Movements in Great Britain, University of London Press, London.

Ellis, J. (1990) ‘Informal Education – A Christian Perspective’ in Jeffs T & Smith M (1990) Using Informal Education: an alternative to casework, teaching and control? Open University Press, Buckingham.

Ellis, J. (1998) ‘Youth Work and Evangelism: Can They Co-Exist With Integrity?’ in Perspectives: reflecting on Christian youth work, Summer 1998, p.10-12, Printworks, Oxford.

Farley, R. (1998) Strategy for Youth Leaders, Scripture Union, Lidcombe.

Ferguson, J. (1981) ‘Introduction’ in Ferguson J (1981) Christianity, Society and Education, SPCK, London.

Fowler, J. (1981) Stages of Faith: the Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. Harper Row, New York.

General Synod Board of Education (1996) Youth A Part: Young People and the Church, Church House Publishing, London.

Heath-Stubbs, M. (1926) Friendship’s Highway, Girls Friendly Society Central Office, London.

Hollins, T. H. B. (1964) Aims in Education: The Philosophic Approach, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Huskins, J. (1996) Quality Work With Young People: Developing Social Skills and Diversion from Risk, Youth Clubs UK.

HMSO (1960) The Youth Service in England and Wales, London: HMSO.

Hubery, D. S. (1963) The Emancipation of Youth, Epworth Press, London.

Jeffs, T. & Smith, M. (1990) ‘Educating Informal Educators’ in Jeffs T & Smith M (1990) Using Informal Education, Open University Press, Milton Keynes.

Jeffs T & Smith M (1996) Informal Education:- Conversation, Democracy and Learning, Education Now Books, Derby.

Jones, M. G. (1968) Hannah More, Greenwood Press, New York.

Mayo, B. (1995) ‘Evangelism among Pre-Christian Young People’ in Ward P (1995) Relational Youthwork: Perspectives on Relationships in Youth Ministry, Lynx, Oxford.

Methodist Association of Youth Clubs (1997) Worship in the Methodist Church.

Methodist Association of Youth Clubs (a) mayc is…

Methodist Association of Youth Clubs (1995) Charter 95.

Milson, F. W. (1963) Social Group Method and Christian Education, Chester House Publications, London.

Rosseter,B. (1987) ‘Youthworkers as Educators’ in Jeffs T & Smith M (1987) Youthwork, Macmillan, London.

Sainsbury, R. (1970) From a Mersey Wall, Scripture Union, London.

Salmon, M. (1988) ‘What Ever Happened to Spiritual Development?’ in Youth in Society No. 136 p10-12.

Smith, M. (1988) Developing Youthwork, Open University Press, Milton Keynes.

The Message (1998 a) and now The News from The Message (Jan).

The Message (1998 b) and now The News from The Message (Sept).

The Message (a) Info Sheet WWMT.

The Message (b) Info Sheet Eden Project Wythenshawe

The Message (c) Eden Wythenshawe.

Theissen, E. J. (1993) Teaching for Commitment: Liberal Education, Indoctrination and Nurture, Gracewing, Leominster.

Tomlinson, D. (1995) The Post-Evangelical, Triangle, London.

Usher, R. & Edwards, R. (1994) Postmodernism and Education: Different Voices, Different Worlds, Routledge, London.

Ward, P. (1997) Youthwork and the Mission of God, SPCK, London.

Ward, P. (1996) Growing Up Evangelical: Youth Work and the Making of a Subculture, SPCK, London.

Ward, P. (1995) ‘Christian Relational Care’ in Ward P (Ed) Relational Youthwork: Perspectives on Relationships in Youth Ministry, Lynx, Oxford.

Warner, H. C. (1942) Christian Youth Leadership in Clubs and Youth Centres, Student Christian Movement Press, London.

Youth For Christ (1999a) http://www.yfc.co.uk/local.htm

Youth For Christ (1999b) http://www.yfc.co.uk/worldwide.htm

Youth For Christ (1997) Review: Annual Report 1996-97, Halesowen.

Youth For Christ (1994) Operation Gideon Year One Training Pack, Halesowen.

Youth For Christ (a) Creative? Musical? Halesowen.

Youth For Christ (b) OpGid: Training you up and taking you further, Halesowen.

Youth For Christ (c) Week in Week out: Taking good news to young people, Halesowen.

Youth For Christ (d) Rock Solid, Halesowen.

Links

Methodist Association of Youth Clubs

Project Eden and the World Wide Message Tribe

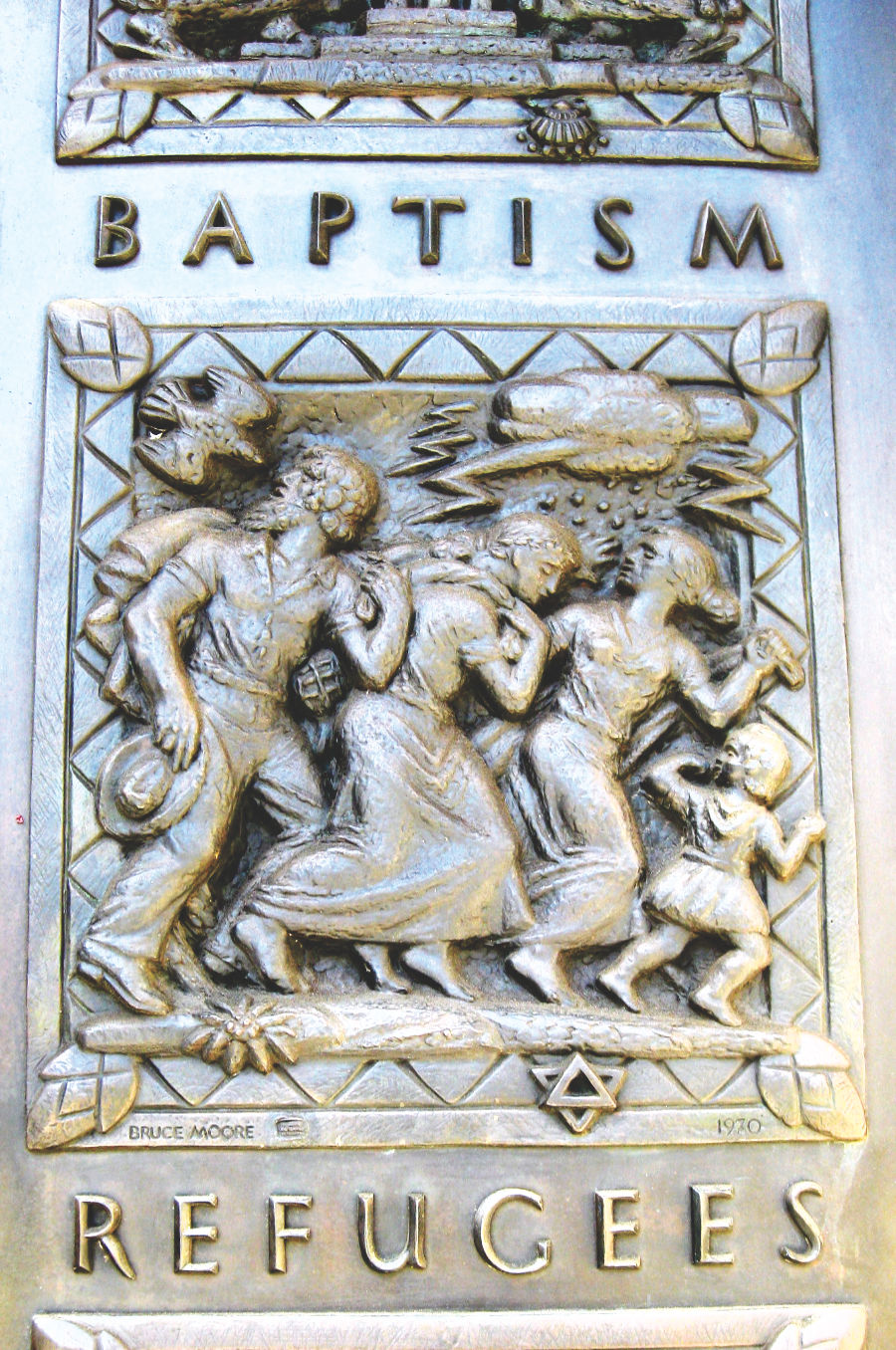

Acknowledgements: The picture – San Francisco, Nob Hill: Grace Cathedral – Old Testament Children’s Doors – is by

Wally Gobetz. flickr | ccbyncnd2 licence.

How to cite this piece: Pugh, C. (1999). Christian youth work: evangelism or social action? The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/christian-youth-work-evangelism-or-social-action/. Retrieved: insert date]

Carole Pugh © 1999

First published in Youth and Policy 65, Autumn 1999. Reprinted with their permission.