Naomi Klein has probably done more than any other commentator, to raise public understanding of the relationships between globalization, capitalism, neoliberalism and climate change. Here we explore her contribution.

contents: naomi klein – life and contribution • no logo, corporations and globalization • the shock doctrine, neo-liberalism and the rise of disaster capitalism • this changes everything – capitalism vs. the climate • conclusion – where next? • further reading and references • acknowledgements • how to cite this piece

Introduction

Naomi Klein (1970- ) is a Canadian journalist, writer and activist known for her critiques of globalization and consumerism, neoliberalism, and the role of capitalism in climate change. Her books – No Logo, The Shock Doctrine and This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate – became international bestsellers and have ‘done more to popularise the inseparability of capitalism and climate change than perhaps any other author’ (O’Brien 2019). In 2018, she joined Rutgers University, the State University of New Jersey as the inaugural Gloria Steinem Endowed Chair in Media, Culture and Feminist Studies.

Early life

Born in Montreal, Naomi Klein’s father was a paediatrician in a public hospital; her mother, a documentary filmmaker. They were both Jewish Americans who had made their way there through their resistance to US military action in Vietnam. Her paternal grandparents were also politically engaged. Involved with the Communist Party from the 1930s, like so many others, they left in 1956. Both were strong unionists. Writing in 2008, Larissa MacFarquhar suggests that the ‘political stories in which Klein places herself all begin in the thirties’.

The thirties and forties were the last time in America, she feels, that social movements were strong enough to force radical economic change in a progressive direction. They were also the last time that a certain kind of grand, bold political hope existed in her family—the last time before events combined to extinguish all thoughts, among Kleins, of utopia. (MacFarquhar 2008)

Unlike her brother Seth, as a teenager, Naomi Klein, ‘resented being dragged to demonstrations’ and reacted against her mother’s feminism and her parent’s hippiness. ‘All my parents wanted was the open road and a VW camper,’ she wrote. ’That was enough escape for them. The ocean, the night sky, some acoustic guitar’ (op. cit.).

In 1989 Klein began her studies in English and Philosophy at the University of Toronto. She had spent some time nursing her mother after she had a stroke (Bonny Sherr Klein 1993). During her first year, the École Polytechnique massacre (also known as the Montreal Massacre) took place. Fourteen women were targeted and killed (the perpetrator said he was ‘fighting feminism’). It was a ‘wake-up call’ for Naomi Klein. She had shied away from activism (Klein 2012a). Her mother’s feminism, work and involvement in, and commitment to, social movements now proved to be a compelling model. ‘Media starts a conversation, but then people take it and act’ (Klein 2012b). Naomi Klein had always wanted to be a writer. Now she began to combine it with activism – editing and writing for The Varsity the University of Toronto student paper.

Then deciding to interrupt her degree studies, Naomi Klein took up an internship with The Globe and Mail, the Toronto-based paper and then went on to edit This Magazine (which had been founded by a group of school activists in 1966) (see THIS).

From No Logo to This Changes Everything

In the mid-1990s Naomi Klein returned to the University to complete her studies. There, according to Larissa MacFarquhar, she found students were no longer so concerned with identity politics but were now talking about economics.

There was a feeling in the air that corporations were getting too powerful—more powerful than governments, but not accountable to anyone except their shareholders. And, at the same time that big corporations were withdrawing physically from the United States and opening factories overseas, visually, even spiritually, they were everywhere, insinuating their logos into what had once been public space. Young activists found this especially objectionable, perhaps because one of the places into which corporations insinuated themselves most effectively was youth and activism, folding mutiny into advertising so deftly that resistance seemed futile. (MacFarquhar 2008)

Klein decided to write a book on branding culture rather than complete her studies. She had also met, and later married, Avi Lewis – a documentary filmmaker who had studied at Toronto. Completed in 1999 and published in 2000, No Logo coincided with, and articulated protests against consumerism and globalization, and the exploitation involved. The book was translated into over 30 languages and sold over a million copies. In The Guardian, it was rated as one of the top 100 non-fiction books of all time. Robert McCrum (2017) comments, ‘Naomi Klein’s timely anti-branding bible combined a fresh approach to corporate hegemony with potent reportage from the dark side of capitalism’.

No Logo was followed by a couple of books of collected essays; two further major – and highly influential – works; and two shorter books – one on the rise of Trump, the other concerned with resistance to ‘disaster capitalism’ in Puerto Rico.

The Shock Doctrine appeared in 2007. Subtitled ‘the rise of disaster capitalism’ this book divided reviewers with, broadly, those already critical of neoliberalism applauding it, and those supporting neoliberalism pointing out Naomi Klein’s ‘faults’. In 2019, The Guardian’s listing of the 100 best books of the 21st century (fiction and non-fiction) put The Shock Doctrine in the top twenty:

In this urgent examination of free-market fundamentalism, Klein argues – with accompanying reportage – that the social breakdowns witnessed during decades of neoliberal economic policies are not accidental, but in fact integral to the functioning of the free market, which relies on disaster and human suffering to function.

Many of the negative reviews for the book came from academic and professional economists complaining of Naomi Klein’s lack of understanding, or appreciation, of economic theory. As we will see, an alternative reading is that Klein understood only too well the shallowness and ideological roots of that theory. Her work helped to prepare the way for the reception to Thomas Piketty’s (2014) work Capital in the Twenty-First Century which argued that neoliberalism produces vastly increased inequalities. Not unexpectedly, it too attracted criticism from economists, but this time they were attacking a critique that came from within.

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the climate came out in 2014 – the same year as another influential work – Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction – An unnatural history appeared. Both Klein and Kolbert were journalists but were coming at the deep problems of climate change from different directions. Elizabeth Kolbert was reviewing the science – charting five mass extinctions on Earth and how humans are causing another. She noted that ‘no creature has ever altered life on the planet’ in the way we are doing now.

Very, very occasionally in the distant past, the planet has undergone change so wrenching that the diversity of life has plummeted. Five of these ancient events were catastrophic enough that they’re put in their own category: the so-called Big Five. In what seems like a fantastic coincidence, but is probably no coincidence at all, the history of these events is recovered just as people come to realize that they are causing another one. When it is still too early to say whether it will reach the proportions of the Big Five, it becomes known as the Sixth Extinction. (Kolbert 2014: 8-9)

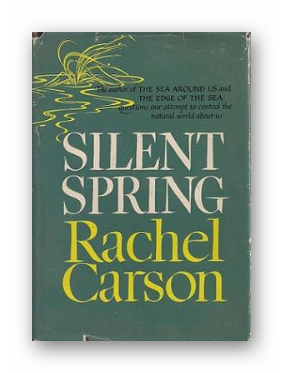

It had been 25 years since the first ‘popular’ text on global warming had appeared (Bill McKibbin’s The End of Nature), and just over 50 years since Rachel Carson’s ground-breaking book on the impact that humans have on ‘the natural world’ (Silent Spring). She finished with a memorable attack on our failure of stewardship for the earth (what Klein  2014 talked about as extractivism – ‘a nonreciprocal, dominance-based relationship with the earth, one purely of taking’ [Klein 2014: 176]).

2014 talked about as extractivism – ‘a nonreciprocal, dominance-based relationship with the earth, one purely of taking’ [Klein 2014: 176]).

The “control of nature” is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man. The concepts and practices of applied entomology for the most part date from that Stone Age of science. It is our alarming misfortune that so primitive a science has armed itself with the most modern and terrible weapons, and that in turning them against the insects it has also turned them against the earth. (Carson 1962: 297)

Klein and Kolbert were able to marshal and generate coherent narratives of the processes of change that appealed strongly to those who were already concerned with the climate emergency. They were, of course, never likely to be listened to by hardened climate change deniers. But they could encourage those (like Naomi Klein herself) who had been avoiding the ‘real truth’ that:

… climate change isn’t an “issue” to add to the list of things to worry about, next to health care and taxes. It is a civilizational wake-up call. A powerful message—spoken in the language of fires, floods, droughts, and extinctions—telling us that we need an entirely new economic model and a new way of sharing this planet. Telling us that we need to evolve. (Klein 2014: 37)

And Naomi Klein had another pressing reason for the change – she had become a mother in 2012. In the past, when fears ’used to creep through my armor of climate change denial, I would do my utmost to stuff it away, change the channel, click past it. Now I try to feel it. It seems to me that I owe it to my son, just as we all owe it to ourselves and one another’ (op. cit.).

Recent work

The rise of Donald Trump led to Naomi Klein returning to the themes of The Shock Doctrine in 2017. She quickly put together No is Not Enough, subtitled Defeating the new shock politics in the UK, and Resisting Trump’s shock politics and winning the world we need in the United States. Unlike the three earlier books which took three or four years to finish, it was written in a matter of months. ‘This book’s argument, in a nutshell,’ Klein (2017) wrote, ‘is that Trump, extreme as he is, is less an aberration than a logical conclusion—a pastiche of pretty much all the worst trends of the past half-century’. She continues:

Most of all, he is the incarnation of a still-powerful free-market ideological project—one embraced by centrist parties as well as conservative ones—that wages war on everything public and commonly held, and imagines corporate CEOs as superheroes who will save humanity. (op. cit.)

Importantly, and an extension of some of her work in This Changes Everything, she also looks to the practical steps to be taken in order to resist.

At this point, Naomi Klein made some significant changes. She formally entered the academic world becoming in 2018 the inaugural Gloria Steinem Endowed Chair in Media, Culture and Feminist Studies at Rutgers University, the State University of New Jersey. Klein also became a senior correspondent at The Intercept, the online news site, that seeks to hold ‘the powerful accountable through fearless, adversarial journalism’ (Intercept undated). Based on work undertaken for The Intercept, she published The Battle for Paradise: Puerto Rico takes on the disaster capitalists in 2018. One consequence of these changes is that she had effectively become US-, rather than Canada-, based.

No logo, corporations and globalization

Some political books capture the zeitgeist with such precision that they seem to blur the lines between the page and the real world and become part of the urgent, rapidly unfolding changes they are describing. (Hancox 2019)

No Logo became a publishing phenomenon and ‘hit at this moment when a global movement was exploding and taking mainstream commentators entirely by surprise’ (Klein quoted by Hancox 2019). Naomi Klein makes clear that the title is not a literal slogan (as in No More Logos), or a post-logo logo.

Rather, it is an attempt to capture an anticorporate attitude I see emerging among many young activists. This book is hinged on a simple hypothesis: that as more people discover the brand-name secrets of the global logo web, their outrage will fuel the next big political movement, a vast wave of opposition squarely targeting transnational corporations, particularly those with very high name-brand recognition. (Klein 2000: xx)

That hypothesis has not (as yet) proved to be correct. However, twenty years on the changes she identifies and explores are there for all to see – and ‘are so much worse than we could have ever predicted’ (Hancox 2019).

No Logo is a book of four parts.

No Space examines how marketing has ensnared culture and education. Here, Klein includes a particularly significant attack on the branding of education (op. cit.: 87-106).

No Choice reflects on the extent to which market-driven globalization may give the impression of diversity – but really homogenization is going on. ‘Dazzled by the array of consumer choices, we may at first fail to notice the tremendous consolidation taking place in the boardrooms of the entertainment, media and retail industries’ (op. cit.: 129).

No Jobs examines the changing experience of work and the rise of self-employment, McJobs and outsourcing, as well as part-time and temporary work. (op. cit.: 195-278)

No Logo argues that these forces involve an attack on ‘the three social pillars of employment, civil liberties and civic space’ and that this, in turn, is feeding anticorporate activism. (op. cit.: xxiii)

One of the great strengths of No Logo is that evidence is drawn from across the globe and woven into an account of changing nature of corporations and the impact this has had on consumers and workers. Its themes were picked up by other writers such as Alissa Quart (exploring branding and teenagers) and Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter in The Rebel Sell: How the counterculture became consumer culture (2005). Heath and Potter comment that ‘No Logo provides a stinging indictment of every aspect of the modern advertising-driven economy’. They continue:

… it is not just that corporations are exploiting our desire to be cool by selling us “cool” products; it is that they are actually creating the desire for those products. We are being systematically duped, manipulated, programmed into the consumerist cool mindset, tricked into buying products we otherwise would not really want. (Heath and Potter 2004: 204-5)

More generally, Naomi Klein was able to delineate and connect some key elements of globalization in a way that made sense to the growing numbers of people concerned about their experiences of education and culture, of contemporary consumerism, and of work. It linked the changing shape of corporations (and capitalism) to globalization. But in the end the ‘vast wave of opposition’ did not happen. The obvious problem with No Logo, according to Heath and Potter (2004: 329) ‘is that despite the rhetoric about the evils of consumerism and its call for “a more citizen-centered alternative to the international rule of brands” the book has very little to offer in the way of positive politics’. This criticism is unfair – and it says more about the writers’ perspective than Klein’s argument. She does set out engaging possibilities and is surely right to explore people-centred alternatives. However, her optimism and hope seem to have led to her underestimating the power of counterforces. Branding has become ubiquitous:

What’s more powerful now… is the idea that every single person has to be their own brand, and the application of the logic of corporate branding to our very selves. It’s an insidious change that has everything to do with social media (Naomi Klein quoted in O’Brien 2019).

The Shock Doctrine, neoliberalism and the rise of disaster capitalism

There are very few books that really help us understand the present. The Shock Doctrine is one of those books. Ranging across the world, Klein exposes the strikingly similar policies that enabled the imposition of free markets… Part of the power of this book comes from the parallels she observes in seemingly unrelated developments. (Gray 2007)

In The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein assembles and explores a wide range of material to critique the actions of politicians and corporate leaders who took on the neoliberal ideas of Milton Friedman and his associates in the Chicago school of economics. In particular, she is concerned with the shock doctrine that was applied in varying degrees to countries as disparate as China, Russia, Iraq, Bolivia, Chile and the UK and USA. Friedman, in a key passage written in 1982 summarizes the doctrine:

Only a crisis—actual or perceived—produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable. (1982: ix)

Milton Friedman and his followers – for more than three decades – had been developing this strategy: ‘waiting for a major crisis, then selling off pieces of the state to private players while citizens were still reeling from the shock, then quickly making the “reforms” permanent’ (Klein 2007: 18). Klein calls these ‘orchestrated raids on the public sphere in the wake of catastrophic events, combined with the treatment of disasters as exciting market opportunities’, disaster capitalism (op. cit.: 15). It is a profoundly anti-democratic process. The only situation in which a population would accept such ‘reforms’ is when it is ‘in a state of shock, following a crisis of some sort—a natural disaster, a terrorist attack, a war’ (MacFarquhar 2008).

It wasn’t necessary for the rich and powerful to create catastrophes so that they could exploit them.

The truth is at once less sinister and more dangerous. An economic system that requires constant growth, while bucking almost all serious attempts at environmental regulation, generates a steady stream of disasters all on its own, whether military, ecological or financial. The appetite for easy, short-term profits offered by purely speculative investment has turned the stock, currency and real estate markets into crisis-creation machines, as the Asian financial crisis, the Mexican peso crisis and the dot-com collapse all demonstrate. (op. cit.: 743-4)

‘Everywhere the Chicago School crusade has triumphed’, Naomi Klein claims, ‘it has created a permanent underclass of between 25 and 60 per cent of the population’. The outcome of the strategy was the creation of what Klein calls the ‘corporatist state’.

Its main characteristics are huge transfers of public wealth to private hands, often accompanied by exploding debt, an ever-widening chasm between the dazzling rich and the disposable poor and an aggressive nationalism that justifies bottomless spending on security. For those inside the bubble of extreme wealth created by such an arrangement, there can be no more profitable way to organize a society. But because of the obvious drawbacks for the vast majority of the population left outside the bubble, other features of the corporatist state tend to include aggressive surveillance (once again, with government and large corporations trading favors and contracts), mass incarceration, shrinking civil liberties and often, though not always, torture. (op. cit.: 32)

The extent to which corporations understand or control these processes is a matter for some debate, according to John Gray (2007) – just as there must be considerable doubt that ‘the neo-liberal ideologues who helped create it foresaw where it would lead. ‘[I]t is hard to resist the suspicion’ he continues, ‘that disaster capitalism is now creating disasters larger than it can handle’ (op. cit.).

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the climate

Extinction Rebellion 2019

Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything again caught a shift in public opinion – and one of great significance. In an article written in 2011 (and reprinted in Klein 2019) she notes that in 2007 a Harris poll found that ‘71 per cent of Americans believed that the continued burning of fossil fuels would cause the climate to change’. Klein continues:

By 2009, the figure had dropped to 51 percent. In June 2011, the number of Americans who agreed was down to 44 percent—well under half the population. According to Scott Keeter, director of survey research at the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, this is “among the largest shifts over a short period of time seen in recent public opinion history.”

Even more striking, this shift has occurred almost entirely at one end of the political spectrum… Today, 70–75 percent of self-identified Democrats and liberals believe humans are changing the climate, a level that has remained stable or risen slightly over the past decade. In sharp contrast, Republicans, particularly Tea Party members, have overwhelmingly chosen to reject the scientific consensus. In some regions, only about 20 percent of self-identified Republicans accept the science. (2011, reprinted in Klein 2019: 73-4)

Eight or more years on, the divide remains underpinned by a dangerous effort to question scientific research in the service of shoring up strong vested interests. The first part of This Changes Everything explores how these processes were added to by the 2007 financial crisis and the austerity programmes that followed – especially in terms of challenges to environmental movements. However, resistance to those vested interests and a resolve to deal with the climate emergency has subsequently strengthened – and the work undertaken by Klein, Kolbert and others has played a significant role.

The power of Naomi Klein’s approach lays in the way she pits capitalism against climate. The bottom line for her is that: ‘our economic system and our planetary system are now at war’ (Klein 2014: 30). Very little she argues ‘has been written about how market fundamentalism has, from the very first moments, systematically sabotaged our collective response to climate change, a threat that came knocking just as this ideology was reaching its zenith’ (op. cit.: 28). Her focus on the ways in which vested economic interests have orchestrated attempts to undermine reputable science, and the work of those highlighting the impact of environmental change in the social and political spheres, sheds considerable light on the situation.

[W]e have not done the things that are necessary to lower emissions because those things fundamentally conflict with deregulated capitalism, the reigning ideology for the entire period we have been struggling to find a way out of this crisis. We are stuck because the actions that would give us the best chance of averting catastrophe—and would benefit the vast majority—are extremely threatening to an elite minority that has a stranglehold over our economy, our political process, and most of our major media outlets. (op. cit.: 27)

What concerns Klein is not so much the mechanics of the transition—the shift from brown to green energy etc. ‘than the power and ideological roadblocks that have so far prevented any of these long understood solutions from taking hold on anything close to the scale required. (op. cit.: 34).

The blocks to progress that Klein critiques include what she describes as ‘magical thinking’. She highlights the ideas that:

- There can be some sort of technological fix to the problems of global warming (op. cit.: 262-296).

- Green Billionaires can save us (op. cit.: 237-260).

- Big business can work with the efforts of ‘big green’ organizations and not blunt them (op. cit.: 199-233).

As Skocpol (2013: 11) argued,

Climate change warriors will have to look beyond elite manoeuvres and find ways to address the values and interests of tens of millions of U.S. citizens. To counter fierce political opposition, reformers will have to build organizational networks across the country, and they will need to orchestrate sustained political efforts.

Naomi Klein builds the case that progressive social movements can make a difference. She does this through a series of case studies. As she states, we now have a few models that ‘demonstrate how to get far-reaching decentralized climate solutions off the ground with remarkable speed, while fighting poverty, hunger, and joblessness at the same time’ (op. cit.: 144).

The environmental crisis—if conceived sufficiently broadly—neither trumps nor distracts from our most pressing political and economic causes: it supercharges each one of them with existential urgency….

Even more importantly, the climate moment offers an overarching narrative in which everything from the fight for good jobs to justice for migrants to reparations for historical wrongs like slavery and colonialism can all become part of the grand project of building a nontoxic, shockproof economy before it’s too late. (op. cit.: 144)

There are mixed lessons from previous social movements – whether it is the fight against slavery and discrimination, the exploitation of workers, or the struggle for women’s rights and around the ability to express our differing sexualities (op. cit.: 457-73). However, the hopes that Klein was expressing in 2014 do appear to have had some life. The development of Extinction Rebellion and the impact of Greta Thunberg and the school strikes for the climate are cases in point (see Klein 2019: 14-53).

John Gray (2014), in his review of This Changes Everything, comments that ‘Klein is a brave and passionate writer who always deserves to be heard, and this is a powerful and urgent book that anyone who cares about climate change will want to read’. He goes on to say that it is ‘hard to resist the conclusion that she shrinks from facing the true scale of the problem’. Neoliberalism and corporate capitalism certainly remain a significant threat to steps to combat climate change but so do geopolitics and the unpredictability of the activities of nation-states in, for example, the Middle East.

Conclusion – where next?

Before turning to the direction in which Naomi Klein is headed, it is worth reflecting on the qualities that she has brought to, and developed in, her work. Here I just want to highlight three.

The journalistic eye. A significant part of Naomi Klein’s contribution is borne of her grounding in journalism. She is not only there at press briefings and key events looking for a story, but she also peers beneath the surface and searches out hidden dynamics. To this must be added something that all the best journalists have, attentiveness to what a wider public might be – and should be – concerned about. This capacity is even more important as many academics have walked away from their responsibilities to enhance public understanding (although possibly less so on the ecological front – see, for example, Lewis and Maslin 2018; Bonneuil and Fressoz 2016). Disappearing into a closed world of journal citations and research assessment exercises, too many have lost sight of their civic responsibilities.

The ability to connect ideas and to communicate. As we have already noted, several reviewers and commentators have underlined Naomi Klein’s capacity to link what could at first seem to be disparate events and phenomenon to wider economic, social and political forces. However, this may have come to very little were it not for her talents as a researcher and writer. She has dug out material, organized it and been able to convey its meaning in an engaging and enlightening way.

A commitment to resisting inequality and injustice. Naomi Klein is dedicated to the causes she is writing about and this is carried through into activism and participation. This is writing that looks to encourage informed, committed action – praxis.

But we need not be spectators…: politicians aren’t the only ones with the power to declare a crisis. Mass movements of regular people can declare one too.

Slavery wasn’t a crisis for British and American elites until abolitionism turned it into one. Racial discrimination wasn’t a crisis until the civil rights movement turned it into one. Sex discrimination wasn’t a crisis until feminism turned it into one. Apartheid wasn’t a crisis until the anti-apartheid movement turned it into one. (op. cit.: 14)

So where next? We find some clues in On Fire: The burning case for a green new deal (2019).

The radicalizing power of climate science

In October 2018, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a special report on Global Warming of 1.5°C. Global warming is likely to reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052 if it continues to increase at the current rate. As Klein (2019: 31) comments, ‘keeping temperatures below the 1.5°C threshold is humanity’s best chance of avoiding truly catastrophic unravelling. But doing that would be extremely difficult’. The press release issued by the IPCC put it like this:

Limiting global warming to 1.5°C would require rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society… With clear benefits to people and natural ecosystems, limiting global warming to 1.5°C compared to 2°C could go hand in hand with ensuring a more sustainable and equitable society. (2018b)

The IPCC Report is significant for its ‘unequivocal clarity’ Klein concludes. When combined with direct and repeated experience with unprecedented weather:

… our conceptualization of this crisis is shifting. Many more people are beginning to grasp that the fight is not for some abstraction called “the earth.” We are fighting for our lives. And we don’t have twelve years anymore; now we have only eleven. And soon it will be just ten. (Klein 2019: 310)

The green new deal

Naomi Klein is also interested in the number of calls to respond to the climate crisis with a Green New Deal.

The idea is a simple one: in the process of transforming the infrastructure of our societies at the speed and scale that scientists have called for, humanity has a once-in-a-century chance to fix an economic model that is failing the majority of people on multiple fronts. Because the factors that are destroying our planet are also destroying people’s quality of life in many other ways, from wage stagnation to gaping inequalities to crumbling services to the breakdown of any semblance of social cohesion. Challenging these underlying forces is an opportunity to solve several interlocking crises at once. (2019: 32-3)

Whether or not this particular formulation has traction, and to take a leaf out of the ‘Disaster Capitalism’ book, we are approaching a moment of profound crisis in which action has to be taken – and this does provide an opportunity, Klein (op. cit.) suggests, to ‘shift to a dramatically more humane economic model’.

Further reading and references

Bonneuil, C. and Fressoz, J. B. (2016). The Shock of the Anthropocene. The earth, history and us. Translated by David Fernbach. London: Verso.

Carson, R. (1962) Silent Spring. Boston: Mifflin.

Friedman, M. (1982) Preface to Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gray, J. (2007). The end of the world as we know it, The Guardian September 15. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/sep/15/politics. Retrieved February 4, 2020].

Gray, J. (2014). This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate review – Naomi Klein’s powerful and urgent polemic, The Guardian September 22. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/sep/22/this-changes-everything-review-naomi-klein-john-gray. Retrieved February 4, 2020].

Guardian, The (2019). The 100 best books of the 21st century, The Guardian September 21. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/sep/21/best-books-of-the-21st-century. Retrieved January 29, 2020].

Hancox, D. (2019). No Logo at 20: have we lost the battle against the total branding of our lives? The Observer August 11. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/aug/11/no-logo-naomi-klein-20-years-on-interview. Retrieved January 28, 2020].

Heath, J. and Potter, A. (2004). The Rebel Sell: Why the Culture Can’t be Jammed. Toronto: HarperCollins.

Heath, J., & Potter, A. (2005). The Rebel Sell: How the counterculture became consumer culture. Chichester: Capstone.

Intercept, The (undated). About the Intercept, The Intercept. [https://theintercept.com/about/. Retrieved January 28, 2020].

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018a). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization [https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/. Retrieved February 4, 2020].

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018b). Summary for Policymakers of IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C approved by governments, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [https://www.ipcc.ch/2018/10/08/summary-for-policymakers-of-ipcc-special-report-on-global-warming-of-1-5c-approved-by-governments/. Retrieved February 4, 2020]

Klein, B. S. (1993). We are Who You are. Feminism and Disability, Abilities 14 pp. 22-26. [https://web.archive.org/web/20071011204526/http://www.enablelink.org/include/article.php?pid=&cid=&subid=&aid=673. Retrieved January 28, 2020].

Klein, Naomi. (2000). No logo: No space, no choice, no jobs. London: Flamingo.

Klein, Naomi. (2002). Fences and Windows: Dispatches from the front lines of the globalization debate. London: Flamingo.

Klein, Naomi. (2007). The Shock Doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. London: Allen Lane. [Page numbers refer to the epub version].

Klein, Naomi. (2011). Capitalism vs. the Climate, The Nation, November 9. Reprinted in Naomi Klein (2019). On Fire: The burning case for a green new deal. London: Allen Lane.

Klein, Naomi. (2012a). The Montreal Massacre, Big Think. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eET3COi8DPY. Retrieved January 28, 2020]

Klein, Naomi. (2012b). Who are you? Big Think. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nS_8KCikaI. Retrieved January 28, 2020].

Klein, Naomi. (2012c). Where are we? Big Think. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PpDN0HhzVDc. Retrieved January 28, 2020].

Klein, Naomi. (2014). This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the climate. London: Allen Lane / Penguin Books. [Page numbers refer to the epub version].

Klein, Naomi. (2017). No is Not Enough: Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Klein, Naomi. (2018). The Battle for Paradise: Puerto Rico takes on the disaster capitalists. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books.

Klein, Naomi. (2019). On Fire: The burning case for a green new deal. London: Allen Lane. [Page numbers refer to the epub version].

Kolbert, E. (2014). The sixth extinction: An unnatural history. London: Bloomsbury Press. [Page numbers refer to the epub version].

Lewis, S. and Maslin, M. (2018). The Human Planet. How we created the Anthropocene. London: Pelican Books.

MacFarquhar, L. (2008). Outside Agitator. Naomi Klein and the new left, The New Yorker December 1. [https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/12/08/outside-agitator. Retrieved January 28, 2020].

McCrum, R. (2017). The 100 best nonfiction books of all time, The Guardian December 31. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/dec/31/the-100-best-nonfiction-books-of-all-time-the-full-list. Retrieved January 29, 2020].

McKibben, B. (1989) The End of Nature. New York: Random House.

Mulgan, G. (2019). Social Innovation. How societies find the power to change. Bristol: Policy Press.

O’Brien, H. (2019). “It feels like everything could tip very quickly”: Naomi Klein takes on the climate crisis, New Statesman, October 30. [ https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/environment/2019/10/it-feels-everything-could-tip-very-quickly-naomi-klein-takes-climate. Retrieved February 4, 2020].

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Trans. Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Quart, A. (2003). Branded: The buying and selling of teenagers. London: Arrow.

Russell, S. (2019). Human Compatible. Artificial intelligence and the problem of control. London: Allen Lane.

Skocpol, T, (2013). Naming the Problem: What It Will Take to Counter Extremism and Engage Americans in the Fight Against Global Warming, paper presented at a symposium on the Politics of America’s Fight Against Global Warming, Harvard University, February. [https://scholars.org/sites/scholars/files/skocpol_captrade_report_january_2013_0.pdf. Retrieved February 4, 2020].

Zuboff, S. (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. London: Profile Books.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to The Internet Archive for being such a great source of older texts.

Images: Naomi Klein presenta en Madrid su nuevo libro “Esto lo cambia todo: el capitalismo contra el clima” 2015. Adolfo Lujan | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence.

Starbucks: Photo by Y. Cai on Unsplash.

Extinction Rebellion 2019 is by Peg Hunter | flickr ccbync2 licence

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2020). Naomi Klein: globalization, capitalism, neoliberalism and climate change, infed.org. [https://infed.org/mobi/naomi-klein-globalization-capitalism-neoliberalism-and-climate-change/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K Smith 2020