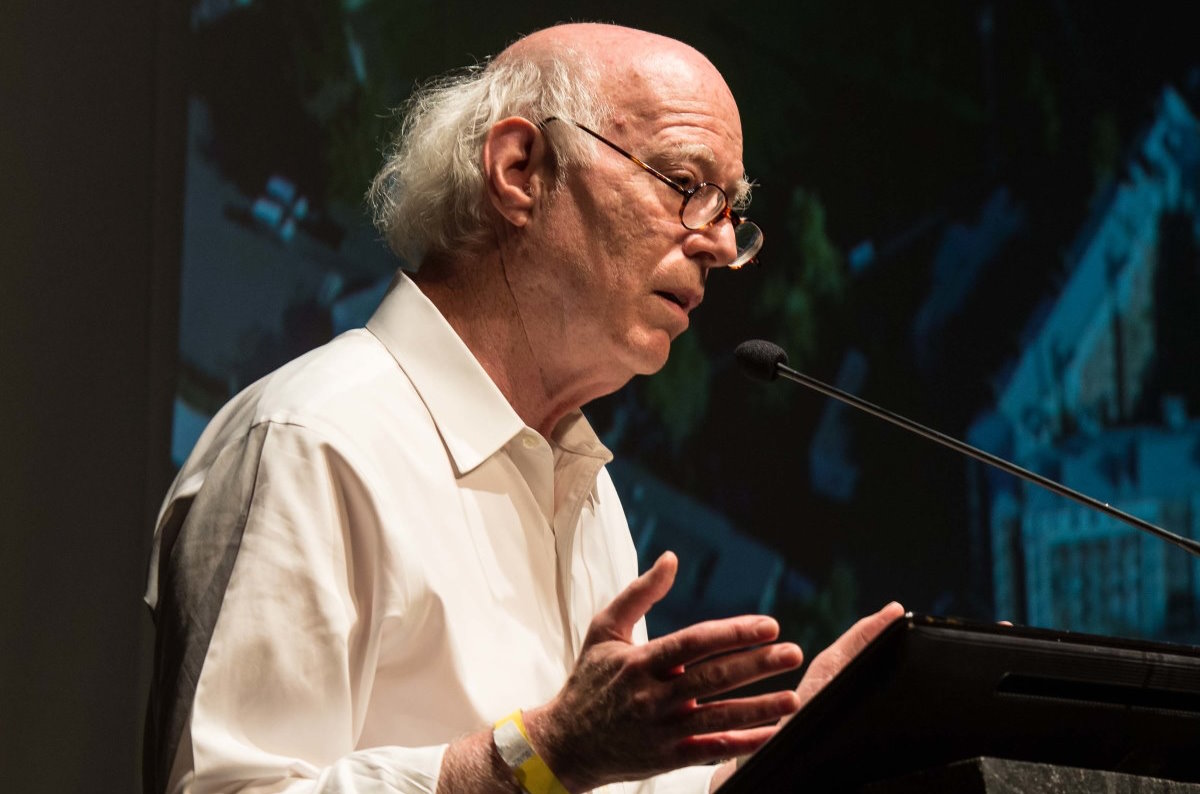

Over 50 years Richard Sennett (1943-) has contributed to our understanding of the experiences of class, capitalism and the life of cities – and our appreciation of Homo faber – humans as makers, users of tools and creators of common life. Sennett is variously described as a sociologist, urbanist, planner and polymath. He is also a musician and novelist. We explore Richard Sennett’s life and work and reflect on his achievements.

contents: Richard Sennett – life • cities and class (and some lessons) • new capitalism and the emotional bonds of modern society • homo faber: craftsmanship, cooperation and building and dwelling • conclusion • further reading and references • acknowledgements • how to cite this piece

Photograph: Richard Sennett 2016 – Deutsche Bank | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence.

Life

Childhood

Born in Chicago in 1943, Richard Sennett’s mother was active in the labour movement, and his father (and uncle) fought in the Spanish Civil War, ‘first against the fascists, and then against the communists’ (Benn 2001). They were members of the Communist Party although it seems likely that his mother left the party after the Hitler-Stalin pact. Interestingly, both his maternal and paternal grandparents had mixed marriages of Russian Orthodox and Russian Jewish partners. After the 1917 Revolution, they fled St Petersburg for Canada – where his paternal grandparents stayed for a while. His maternal grandparents went to Chicago where his grandfather – who was a mathematician – went to work for the General Electric Corporation.

Around seven months after Richard was born, his father returned to Spain and stayed on there, after hostilities ceased. Sennett was brought up by his mother, Dorothy. He has described her as a ‘remarkable woman and a fantastic writer. She had wanted to be a writer in the 30s but after my father left, she was down on her luck and her dream was shattered’ (op. cit.). She was not on good terms with her grandfather at that time (in part because of her political commitments) and there was not a lot of money coming in to support Sennett’s upbringing.

From 1946 to late 40s they lived on the Cabrini Green public housing project in Chicago. The project had replaced poor housing where the conditions had earned the area the nickname of the ‘Little Hell’. The area had been the site of the ‘slum’ described in Harvey W. Zorbaugh’s classic (1929) The Gold Coast and the Slum: A Sociological Study of Chicago’s Near North Side. The new development was at first seen as a welcome change. The first phase which opened in 1942 involved relatively low-rise buildings. The high-rise blocks were completed in 1957. Cost-cutting measures ‘taken during the construction of the towers led to quick deterioration, and there was little money budgeted for desperately needed maintenance’ (Reed 2015). Things were also made worse by overcrowding (there were up to 15,000 people living there), poverty, a lack of policing and rising crime rates.

The Cabrini Green public housing project in Chicago by

Jet Lowe | Wikimedia PD

Sennett has written about the neighbourhood in Respect in a World of Inequality (2003: 7):

Originally Cabrini was meant to be 75 per cent white and 25 per cent black. By the time it opened its doors, those percentages were reversed. My mother remembered many middle-class white people driven by the housing shortage into the project, but statistically, middle-class residents were few in number and the first to escape. Other whites, destined to stay longer in Cabrini Green, included wounded war veterans who could not work full-time, and the authorities had also lodged among us some mental patients not ill enough to remain in hospital but too fragile to live on their own. This mixed community of blacks, the white poor, the wounded, and the deranged framed the subjects of the experiment in social inclusion.

Sennett loved music and began playing the cello around the age of five. He also played the piano.

We may well have seemed strange to our new neighbours, the two rooms filled with books and classical music. I imagine, moreover, that our temporary poverty did not carry the same stigma it might have inflicted on many of our white neighbours. (Sennett 2003: 9)

Richard Sennett’s mother, Dorothy Skolnik Sennett, had trained as a social worker at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration (1939–40) studying with Charlotte Towle (Station 2011). She was keen to move out of the project. Alongside concerns around Richard growing up in the area –there were increasing tensions in the community. There was the possibility that as a social worker she would be drawn to deal with problems.

With an American turn of the social kaleidoscope, our fortunes slowly improved. When we left Cabrini, my still-single mother began to make her way as a social worker and my music began to flourish. Though no boy prodigy, I composed, played the cello, and started performing. It was through learning an art that I began to leave others behind. (Sennett 2003:14)

Richard Sennett started school in Chicago. It was Catholic and run by nuns of the Order of the Blessed Virgin. He has recounted that it used corporal punishment, which was ‘particularly difficult for Black parents who thought these were southern racists who had come to get them’ (Interview with Alan Macfarlane 2009). However, it placed a very strong influence on helping the children to achieve. At the age of eleven, they left Cabrini Green and moved to Minneapolis where his mother worked for around four years as a social worker. He attended military and then public schools (Sennett 1972: 8). Eventually, they settled in Washington, DC, but by this time Sennett was also touring with a Bach cantata group in parts of the mid-West, and a little in Chicago and New York.

Melissa Benn (2001) has suggested that the political commitments and orientations of his family – are central to understanding his work. It can be understood as ‘a life-long attempt to come to terms with his radical heritage, to both honour the idealism of an old left and re-mould it in the light of contemporary realities’. Those commitments may well be a significant touchstone, but four other things also shine out.

First, there is his lived experience of city life with its contrasts, tensions and opportunities, and Sennett’s first-hand knowledge – as a young inhabitant – of different multicultural built environments.

Second, Richard Sennett’s embrace and experience of music provided him with both a paradigm and key themes for exploration as a sociologist. These included the process by which skills are acquired, the nature of the cooperation involved in playing together (and the level of detachment also required) and different forms that dialogue takes (Richard Sennett talks about this in his 2009 interview with Alan Macfarlane).

Third, he grew up in an environment where intellectual activity and writing was prized – both his mother and his schooling enabled him to explore ideas.

Last, there is a very real sense in which he was different as a child to many of his peers. He was, he has said, very sociable – and has continued to be. Music and books were significant markers, but he appears to have been able to negotiate his way through different social situations. The circles in which he and his mother moved were also significant. ‘We had a tough time financially, but in the bohemian, radical milieu in which we lived, we were just another family,’ he has said. ‘It had a curious class composition, this world. Most were Jewish, but it was a cultural milieu, not an ethnic one’ (Benn 2001).

University

In 1960 Richard Sennett returned to Chicago to study with Frank Miller, principal cellist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Sennett has commented, ‘I would have been very happy to just study with him privately, but I would have been instantly drafted. So, I went to the University of Chicago, and I loathed it’ (Station 2011). He might not have liked it, but Richard Sennett went on to earn a history degree and formed important relationships. One was with Christian Mackauer, his Western Civilization teacher. ‘He was a kindly man and very worldly, and he introduced me to Hannah Arendt,’ Sennett says. They ‘were two older teachers that I really found to be wonderful supports’ (op. cit.). However, the call of music was strong. He interrupted his course to study cello and conducting at Juilliard in New York during his second year. Sennett spent nine months there but was driven back to the University of Chicago by the threat of being drafted to serve in Vietnam. Unfortunately, he also developed carpal tunnel syndrome, which required an operation on his hand in 1964 that went wrong (Sennett 2003: 23-5). The door to professional music was closed.

Luckily, another door opened. He had come to know David Riesman (1909-2002) – famous for his 1950 study The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character, written with Nathan Glazer, and Reuel Denney. (Sennett knew Reisman’s son (who was a composer) and, also, performed with his daughter Jenny (she was a singer). David Riesman had taught at the University of Chicago up to 1958 and was now at Harvard and collaborating with Christopher Jencks on what was to be another classic study, this time of higher education: The Academic Revolution. Riesman invited Sennett to Harvard and to undertake a PhD. Sennett had become:

… interested in cities and ways that social class, economic opportunity, and family life played out in urban communities. “Since I wasn’t going to be able to perform, I sort of just moved into sociology.” (Benn 2001)

Alongside David Reisman, who was committed to working with his students, Richard Sennett was also lucky enough to get to know Reisman’s colleague, Erik Erikson (1902-94) – the developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst. Erikson was well known for his work on developmental stages and identity crises – Childhood and Society (1950) and was working on Identity: Youth and Crisis (1968). He was also, like Riesman, keen to support students on personal journeys. Sennett comments,

What most struck me about him was a quality all good clinicians possess, his capacity to listen steadily as we thrashed about, Erikson puffing on the small Danish cigars he then favoured but remaining otherwise immobile. (2003: 29)

He continues:

Erikson and Riesman were friends, or perhaps it’s better said that they were complicit; for different reasons both felt outsiders in that bastion of official thought. As teachers, neither was disposed to point the way forward along a clear path. Erikson pondered to himself when he lectured; Riesman suggested twenty books you might read, and ten people whom you should telephone, to pursue whatever it was you were pursuing.

Each in his own way, Erikson and Riesman felt oppressed by the waste of life which surrounded them in Harvard, a university filled with so many very bright kids. (2003: 30)

This meant that by the time he completed his PhD (Mid-city; a study of family life and social mobility in the nineteenth century) in 1969, he had come to know, and be influenced by, three notable outsiders who were highly influential in their different fields. Reisman had helped to ground him in a ‘sociological imagination’ and analysis. As well as supporting Sennett in his PhD study, it was through a conversation with Erik Erikson on a walk one morning in a New England graveyard had prompted him to think about personal identity and city life (which came to fruition in The Uses of Disorder [1970]). Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) provided him with, among other things, a space to explore and argue about ideas; a model of great courage; and an overarching theme – Homo faber – for his trilogy of books on craftsmanship, cooperation and building and dwelling (Sennett 2008, 2012, 2018).

Richard Sennett had got to know Arendt around the time she published Eichmann in Germany (1963) and was under fierce attack from different directions. She had entered what she described as her ‘second exile’ (Macfarlane 2008). Sennett describes her as a ‘wonderful person to be with’; as someone who ‘loathed people who sucked up to her’; and as a ‘great teacher who loved argument’. ‘Prudence’, he comments’ was not a word you would attribute to her – everything was a categorical declaration’ (Interview with Alan Macfarlane 2009). In addition to these three, Sennett had also been supervised by the historian Oscar Handlin (1915-2011) (Feeney 2011) and was appreciative of the support and encouragement he had been given (Sennett 1970a: viii).

Career

Richard Sennett has held positions at several universities:

- Yale University, lecturer in the Department of Sociology (1968-1970). In 1968 Richard Sennett also founded and co-directed from 1969 to 1974, with Christopher Jencks and Gar Alperowitz, the Cambridge Institute in Cambridge (Massachusetts).

- Brandeis University, assistant professor (1970-1972)

- New York University, Professor of Sociology and History (1972-1998). One of Sennett’s key actions at the university was the establishment of the New York Institute for the Humanities, and acting as a director until 1984. Richard Sennett is now a Professor Emeritus | Professor of the Humanities.

- London School of Economics (1999-2010) Centennial Professor of Sociology (shared with New York University). Since 2010 he has been an Emeritus Professor.

Richard Sennett is a Senior Advisor to the United Nations on its Program on Climate Change and Cities. Also, he is Senior Fellow at the Center on Capitalism and Society at Columbia University and Visiting Professor of Urban Studies at MIT.

Between 1989 and 1993, Sennett was the chairman for the International Committee on Urban Studies, funded by UNESCO and the Rockefeller Foundation.

As well as writing as a sociologist/urbanist, Richard Sennett has also written three novels: The Frog who Dared to Croak (1982), An Evening of Brahms (1984) and Palais-Royal (1987) [click for more details].

Private life

Melissa Benn (2001) has commented that on his private life Richard Sennett is ‘guarded to a point of gracious stubbornness’. He did volunteer ‘I married very young and I divorced young’ (both, apparently in 1968). He married again in the 1970s to Caroline Rand Herron (1941-2016) a journalist and reviewer with The Partisan Review (1963-1978) who went on to work at The New York Times (up until 2005). Herron was also involved in his work with New York Institute for the Humanities and appears several times in the acknowledgements of his books.

He is now married to Saskia Sassen (1948- ), a Dutch-American sociologist known for her work on globalization (she is credited with inventing the term ‘global city’) and migration (1988, 1991, 1999, 2006). Saskia Sassen is the Robert S. Lynd Professor of Sociology at Columbia Universityco-chairs its Committee on Global Thought.

Sennett continues to play the cello – having had further corrective surgery – and plays in a small chamber group. He did suffer from a serious stroke some years ago – and he has commented on some of the impacts it had:

In recovering from it, I began to understand buildings and spatial relations differently from the way I had before. I now had to make an effort to be in complex spaces, faced with the problem of staying upright and walking straight, and also with the neurological short-circuit that in crowds disorients those affected by strokes. Curiously, the physical effort required to make my own way expanded my sense of the environment rather than localized it to where I put my foot next, or who is immediately in front of me; I became attuned on a broader scale to the ambiguous or complex spaces through which I navigated. (Sennett 2018: 25)

Cities and class (and some lessons)

We can learn a lot about the direction and nature of Richard Sennett’s subsequent writing and thinking from the first three books that appeared after he completed his PhD.

While other social historians might get caught up in documenting the mundane details of everyday life, Sennett has displayed a remarkable ability to see the big picture and ask the big questions that have brought deep meaning to this new mode of history. (Harvard University 2017)

In the same year that Families Against the City appeared, a rather different book also hit the shelves. The Uses of Disorder. Personal identity and city life aimed to convince its readers that the ‘jungle of the city, its vastness and loneliness, has positive human value’ (Sennett 1970b: xvii). He argues that:

… there appears in adolescence a set of strengths and desires which can lead in themselves to a self-imposed slav

ery; that the current organization of city communities encourages men to enslave themselves in adolescent ways; that it is possible to break through this framework to achieve an adulthood whose freedom lies in its acceptance of disorder and painful dislocation; that the passage from adolescence to this new, possible adulthood depends on a structure of experience that can only take place in a dense, uncontrollable human settlement—in other words, in a city.

Uses of Disorder takes the essay form that was also to be a characteristic of much of his work. It takes an interesting idea – here that many people become stuck in perpetual adolescence – and then asks if the diversity and anarchy of city life can be adapted to foster creative disorder. The first half of the book explores what he sees as a new puritanism – and its expression in identity, the myth of a purified community and in planning. Part two of the book discusses a new anarchism – and the city as an anarchic system. The book doesn’t have footnotes, a bibliography, or an index. It is serious, develops an argument but does not follow a conventional academic route – which of course annoyed some. However, it was loved by many readers looking to make sense of their experiences of city life at that point and of the changing cultures around them. It fell nicely in place beside the efforts of Paul Goodman, Ivan Illich and Jane Jacobs to change the way we view cities, institutions like schools and the formation of identities.

[W]e began to see from the first interview on that urban laborers themselves, no less than their critics, are aware of the momentous change in their lives the decline of the old neighborhoods has caused; these workingpeople of Boston are trying to find out what position they occupy in America as a whole… For the people we interviewed, integration into American life meant integration into a world with different symbols of human respect and courtesy, a world in which human capabilities are measured in terms profoundly alien to those that prevailed in the ethnic enclaves of their childhood. (op. cit.: 18)

It looked to the significance of dignity and respect. Everyone is subject to a scheme of values whereby they validate self by wearing ‘badges of ability’ to win respect – both from others and themselves.

Class society takes away from all the people within it the feeling of secure dignity in the eyes of others and of themselves. It does so in two ways: first, by the images it projects of why people belong to high or low classes—class presented as the ultimate outcome of personal ability; second, by the definition the society makes of the actions to be taken by people of any class to validate their dignity—legitimizations of self which do not, cannot work and so reinforce the original anxiety.

The result of this, we believe, is that the activities which keep people moving in a class society, which make them seek more money, more possessions, higher-status jobs, do not originate in a materialistic desire, or even sensuous appreciation, of things, but out of an attempt to restore a psychological deprivation that the class structure has effected in their lives. In other words, the psychological motivation instilled by a class society is to heal a doubt about the self rather than create more power over things and other persons in the outer world. (Sennett and Cobb 1972: 170-1)

In The Hidden Injuries of Class, Sennett and Cobb succeed in highlighting important questions about the experiences of many workers – and the significance of respect and dignity. Crucially, the book was put together in a way that engaged a readership well beyond the academy. Not unexpectedly, various criticisms were thrown at it: women’s experience was not a focus, not how things were played out within different social groupings; and nor did it conform to conventions around what might constitute a scholarly text in this area. In the case of the latter, some of the responses to the book mirror the reaction to Riesman’s et. al. classic, The Lonely Crowd. This how Seymour Martin Lipset and Leo Lowenthal put it concerning that book:

Whereas the book greatly impressed the intellectual community at large, it failed to impress many sociologists. Some of them tended to react to The Lonely Crowd as just another, perhaps more brilliant, literary critique of the society; their most polite formula has been to say that “The Lonely Crowd may be a good book, but it certainly is not sociology.”

This reaction to a book written by a professor of sociology about American society is indicative of certain unfortunate current developments in sociology. The concern of the discipline focuses on the development of a formal body of technical theory, which seeks to specify precise variables and to formulate rigorously testable hypotheses. By having this aim in mind, sociologists define themselves outside of the world of the intelligentsia and no longer contribute to the informed conversation of the day. In turn, topics of broad import, but which are difficult to treat exactly or quantitatively, are no longer considered within the purview of the discipline. (1962: viii)

Ten years later, it seems little had been learned in this area of the Academy – and the situation remains the same another fifty years on. It is necessary to develop ways of talking about social theories and questions that engage the public, deepen understanding and point to ways of improving our life together.

Some lessons

In these three books, we see Sennett the historian, Sennett the essayist, and Sennett the sociologist. We can also see the beginnings of Sennett the public intellectual. These personas can be found in much of his subsequent work, but it is the essayist that seems to dominate his writing. As an observer of emerging social trends and the changing shape of modern society, he points to experiences and dynamics that need careful attention. His work is full of interesting observations and helpful pointers; it helps us to recognize and appreciate the phenomenon in question. However, as we will see, it can only take us so far:

Richard Sennett the historian tends to focus on moments and instances that support the line of argument rather than engage fully with the historical contexts involved. This can be seen in his next, and later, books The Fall of Public Man (Sennett 1977) and Flesh and Stone (Sennett 1994). In the first of these, for example, he argues that the full flowering of public life could be found in eighteenth-century London and Paris – and that we are now oriented to narcissistic forms of intimacy and self-absorption that undermine participation in public life. This exploration brings out some interesting lines of exploration, for example around ‘the reality and worth of impersonal life’ but was it this way? Talking about the critiques of historians by post-modernist theorists and critics, Richard J. Evans argued that objective historical knowledge is both desirable and attainable, but that involves a certain disposition and practice.

I will look humbly at the past and say, despite them all: It really happened, and we really can, if we are very scrupulous and careful and self-critical, find out how it did and reach some tenable conclusions about what it all meant. (Evans 1999: 220)

Sennett’s use of historical example could well say more about the writer, his times and his ideas and ideologies than what was going on then (to paraphrase E. H. Carr 1961).

Richard Sennett the sociologist does not engage with social theory in a sustained way nor does he construct worked-through analytical or conceptual frameworks. Sennett does make links to the work of different theorists and writers and draws ideas from a wide range of sources. That said, there is little ongoing conversation with core concepts, and little attempt to build theory in the way that, for example, Jürgen Habermas, Pierre Bourdieu or Michel Foucault do. The comparison with Michel Foucault (1926-1984) is instructive in part, as Sennett has written with him, in part as he also drew from disparate sources and was not a particularly systematic thinker (Taylor 2011). Foucault was, in his own words, an ‘experimenter’. ‘I write in order to change myself and in order not to think the same thing as before’ (2000: 240). The difference is that Foucault paid careful attention to developing his own approaches to historical method (archaeological and genealogical); developed new understandings of core sociological concepts such as power and subjectivity (that have become part of an ongoing conversation within the area); and looked to the underlying structures that form the context for thinking (see, for example, Foucault 1966). Sennett’s chosen form – the extended essay – and his orientation lend themselves to social criticism or social commentary, rather than the development of social theory. This is not a bad thing, but it means others have to do the work in this area.

Richard Sennett the public intellectual does not attempt sustained political analysis. Again it is helpful to compare his work with others. Foucault’s concern with power, for example inevitably took him towards this territory and his later political engagement fed through into work such as Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la prison (Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison) (1975). However, one of the most interesting comparisons is with C Wright Mills (1916-1962) partly because they shared a concern with craftsmanship as a focus for exploration. Mills was famously critical of what passed for sociology in the United States but directly contributed to core debates in the subject for example around the work of Max Weber, the relationship between character and social structure, power and class (see the discussion in Smith 2009). Mills also used the essay form both in works of social and political criticism such as Listen Yankee and in shorter articles (see Mills 1963; Horowitz 1983). If we look at an article from 1944 – The social role of the intellectual – we find writing not unlike Sennett’s:

We continue to know more and more about modern society, but we find the centers of political initiative less and less accessible. This generates a personal malady that is particularly acute in the intellectual who has labored under the illusion that his thinking makes a difference… (1963: 293)

What then follows is a political and sociological discussion examining the cooption of intellectuals and the extent to which ’many are betrayed by what is false within them’ (op. cit.: 304). Mills might not have been liked by many of his academic colleagues, but was able to engage in social criticism and use the essay form because he appealed to core theoretical concerns, and had himself created a body of serious social and political analysis.

New capitalism and the emotional bonds of modern society

Richard Sennett continued to explore the injuries of class, the ‘emotional bonds of society’, and the nature of cities. Here I want to focus on three essays exploring authority and the emotional bonds of modern society; the personal consequences of work in the new capitalism; and respect in a world of inequality. The first and the last are separated by 23 years and the first and second are interrupted by three novels and The Conscience of the Eye (on the design and social life of cities) (1991) and Flesh and Stone: The body and the city in western civilization (1994).

Authority (Sennett 1980) was supposed to be the first of four essays on the emotional bonds of modern society. ‘I want to understand how people make emotional commitments to one another, what happens when these commitments are broken or absent, and the social forms these bonds take’ (op. cit. ). It didn’t quite work out as a series of essays – but the three further themes he wanted to explore – solitude, fraternity and ritual do appear in varying degrees in later works. However, as Zygmunt Bauman (1982) commented in his review of Authority, the volume stands ‘on its own as a self-contained, highly imaginative and, in a number of senses a revolutionary study’.

It is revolutionary, to start with, regarding the semantic field in which we habitually (again, since Weber) locate the concept of authority: authority is legitimate power. People obey commands because they believe that whoever gave them, did so of right. The question of authority, therefore, is subsidiary to the question of legitimation. To find out why people obey, one should study the ways in which they legitimise the right to command. Conversely, disobedience arises once legitimation loses its credibility. Rebellions against powers-that-be follow (or entail) a ‘legitimation crisis’. All these beliefs fit well with the view of authority and willing obedience as, essentially, the matter of reason and rational judgement.

The refusal to treat reason and passion as two mutually independent faculties and alternative bases of human behaviour disengages the idea of authority from this of legitimation and paves the way to consider seriously what is the most typical manifestation of power in modern society: the ‘bond of rejection’ In its various forms, of which ‘disobedient dependence’ Sennett presents most comprehensively and cogently. It also renders the grip of authority largely independent from its rationally articulated legitimation. And it casts a shadow of doubt on the identification of ‘legitimation crisis’ with the disintegration of power systems. (op. cit)

Richard Sennett argues that disobedient thoughts and actions tend to reproduce and reaffirm the significance of authority.

The Corrosion of Character (Sennett 1998) is, in many respects, a step on from the analysis and focus of The Injuries of Class. He explores the impact of new (flexible) capitalism on the experience of workers – and uses his, by now, classic approach drawing on examples from people’s lives, and making links with different historical moments, writers and ways of thinking. He argues that the system of power inherent in modem forms of flexibility consists of three elements: ‘discontinuous reinvention of institutions; flexible specialization of production; and concentration of without centralization of power’ (1998: 47). One of the conclusions he reaches is that the experience of flexible capitalism is arousing a longing for community.

All the emotional conditions we have explored in the workplace animate that desire: the uncertainties of flexibility; the absence of deeply rooted trust and commitment; the superficiality of teamwork; most of all, the spectre of failing to make something of oneself in the world, to “get a life” through one’s work. All these conditions impel people to look for some other scene of attachment and depth. (1998: 138)

The ‘we’’ of ‘community’ can be seen as an act of self-protection; a defence expressed as a ‘rejection of immigrants or other outsiders’ (op. cit.). Modern capitalism, according to Sennett, ‘radiates indifference’ and portrays system failures as individual ones. ‘ There is history, but no shared narrative of difficulty, and so no shared fate. Under these conditions, character corrodes; the question “Who needs me?” has no immediate answer’ (op. cit.: 147).

The emerging trends in the new capitalism that Sennett identified still provide a helpful reference point. For example, flexible capitalism appears to have aroused a longing for community and has been expressed, for example, in the social habits of ‘millennials’. One element has been their ‘insatiable appetite for collaboration and always-on connection to the web, and that is a private online community’ (Gopinath 2015). However, set against this is that a significant section appears to place a greater value on the importance of in-person interactions and relationship building the preceding generations. Many value collective action and networks, are influenced by peers and are more likely to be activists (see, for example, The Case Foundation [2019]).

Respect in an age of inequality (Sennett 2003) links closely with The Corrosion of Character. It started as a companion volume on welfare but changed:

Welfare clients often complain of being treated without respect. But the lack of respect they experience occurs not simply because they are poor, old, or sick. Modern society lacks positive expressions of respect and recognition for others. (Sennett 2003: xv)

The resulting book, as Jenny Turner (2003) comments, brought together two key themes in his work. The first is ‘how people bring with them into their social lives all sorts of secret doubts and painful questions to do with pride, love for others and self-worth’. The other concerns the significance of ‘formality, structure, authority in the social arena’. It combines a significant element of memoir with attention to contemporary phenomena and moral philosophy.

Respect’s publication was accompanied by some very positive press reviews. As Alain de Botton, writing in the Daily Telegraph, notes Sennett ‘considers the inequalities of modern society from a distinctive angle. Instead of focusing just on financial inequalities, he looks at the inequalities that exist in what he calls “respect” (2003). As might be expected pinning down what is meant here by respect is difficult: It can involve recognizing and honouring another; it certainly entails dignity. Mutuality is also involved and expressed. There is also the relationship between respect for others and self-respect. Sennett concludes:

In sum, if behavior which expresses respect is often scant and unequally distributed in society, what respect itself means is both socially and psychologically complex. As a result, the acts which convey respect—the acts of acknowledging others—are demanding, and obscure. (2003: 59)

Taking the three essays together

In these three books, we find Sennett:

- unlinking authority from legitimation and this opens up exploration of the most typical manifestation of power in modern society (Bauman 1982).

- identifying trends in capitalism – a discontinuous reinvention of institutions; flexible specialization of production; and concentration of, without centralization of, power.

- highlighting some processes that create and sustain inequalities in respect.

What we lose in the separation of these into separate essays, is how these relate to each other – and, in particular, how we are to conceptualize power. Having brought us this far, Sennett could have made a major contribution – perhaps looking across to Foucault’s discussions of power, and exploring other key writers like C Wright Mills (1956), Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002), Steven Lukes (1974, 2005) (who, like Sennett, has also worked for many years at NYU) and Michael Mann (2013).

This said he does return to the culture of the new capitalism (Sennett 2006). In a series of lectures delivered at Yale in 2004, he argued that only a certain kind of human being can prosper in unstable, fragmentary social conditions. This involves addressing three challenges.

- Managing short-term relationships, and oneself, while migrating from task to task, job to job, place to place.

- Developing new skills as demands shift.

- Letting go of the past. (op. cit.: 4)

While we may be living in a ‘liquid modernity’ (Bauman 2000), Sennett argues, changes in work and consumption have not set people free.

Homo faber: craftsmanship, cooperation and building and dwelling

This series of books started as an exploration of different aspects of material culture. They were to address the issue of technique as a ‘cultural issue rather than as a mindless procedure’ (Sennett 2008: 8). The first was to be about craftsmanship – the skill of making things well; the second to address the crafting of rituals that manage aggression and zeal (with the working title of Warriors and Priests); and the last (The Foreigner) to explore ‘the skills required in making and inhabiting sustainable environments’ (op. cit.). As with the series to be started by Authority (see above) thankfully things did not turn out as intended. ‘Thankfully’ as one of Sennett’s great characteristics is that he is an explorer, he allows what he is seeing to speak. In this case, when researching and writing The Craftsman he was ‘struck again and again by a particular social asset in doing practical work: cooperation’ (2008: ix). This then became the focus of the second book in the series – Cooperation (2008). It was another 10 years before the third volume Building and Dwelling. Ethics for the city (2018) appeared. This book ‘puts Homo faber in the city’ (2018: 27) and the fault line between the lived and the built.

Homo faber

The Latin term Homo faber is often translated as ‘humans as makers’ (fabricators and craftsmen). In the twentieth century, it was associated with the work of Henri Bergson (1907) and his belief that humanity is defined by intelligence which is, in turn, identified by the ability to make tools (Lawler 2016). It was also the title of a novel by Max Frisch (1911-91) in which his central character Walter Faber ‘considers life a technical problem that can be solved through skill and rational methods’ (Koepke 1991: 70). The result of this orientation, Frisch seems to be suggesting, is often inhumane and destructive. However, here we begin with the work of Hannah Arendt (1958; 2002).

Hannah Arendt (1906-75) – who, as have seen, was something of a mentor to Richard Sennett – famously argued that modernity involved a victory of animal laborans over Homo faber. The former entailed a valuing of productivity, abundance and life; the latter values associated with craftsmanship and fabrication – stability, durability and permanence, and those linked to the world of political and social action and speech — freedom, plurality, solidarity (d’Entreves 2019). The ‘ands’ are important. Acts of making have to be guided by politics dialogue and historical understanding – and to take their place in the world rather than acting upon it.

For a man can be “eloquent in word and vigorous in deed,” but neither words nor deeds leave behind a trace in the world. Nothing bears witness to them after the brief moment in which they pass through the world like a breeze or a wind or a storm and shake the hearts of men. Without the tools that Homo faber designs in order to ease men’s labors and shorten their hours of work, human life would be nothing but toil and effort. Without the permanence of the world that outlasts mortal man’s span of life on earth, the races of man would be as grass, and all the glory of man as the flower of grass, and without the productive arts of Homo faber — but now at the highest level in the full glory of their purest development — without the poets and the historians, without the arts of forming and narrating, the only thing that speaking and acting men are able to produce — namely, the history in which they appear as actors and speakers until it has proceeded to the point that someone can report it as history — that history would never impress itself on the memory of man so that it became a part of the world in which men live. (Arendt – Vita activa translated by David Dollenmayer and quoted by Knott 2014: 70).

Homo faber is Arendt’s image of men and women ‘making a life in common’ (Sennett 2008:6). However, as Richard Sennett points out, there may not be quite the stark differentiation between Animal laborens and Homo faber that Arendt appears to be arguing for. It might not be that the mind ‘engages once labour is done… (perhaps) thinking and feeling are contained within the process of making’ (op. cit.: 7). This is the starting point for The Craftsman.

Craftsmanship

For Sennett craftsmanship, ‘names an enduring, basic human impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake’ (2008: 9). However, the craftsman often faces ‘conflicting objective standards of excellence; the desire to something well for its own sake can be impaired by competitive pressure, by frustration, or by obsession’ (op.cit.). S/he conducts a dialogue between concrete practices and thinking and this ‘evolves into sustaining habits, and these habits establish a rhythm between problem-solving and problem finding’. The book looks to build several arguments including:

- Skills begin as bodily practices.

- Technical understanding develops through the powers of imagination

- Motivation matters more than talent.

In the process Richard Sennett draws upon, and discusses, a range of examples including his own interests in music and buildings; the work of Dennis Diderot (1713–1784) in putting together the 35 volumes of his Encyclopédie des arts et des métiers between 1751 and 1780 (Sennett 2008: 90-106); John Ruskin’s (1819-1900) seminal discussion of craft in The Stones of Venice (1851-53) (op. cit.: 108-188); craft in the UK National Health Service (op. cit.: 46-50); technique and touch (op. cit.: 149-178); the open-source development of Linux; and the zen of archery (op. cit.: 214-226). It is classic Sennett, full of engaging insights and interesting lines of thought. It sparkles – but how far does it take us forward?

First, and in line with what has been said about his earlier work, the use of examples from diverse arenas of practice does not properly allow for sustained reflection on the processes and dispositions (haltung) of craft work. It is instructive to place The Craftsman against a rather different book by Peter Korn (2015) Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman. Like Sennett, Korn mixes memoir, polemic and philosophical reflection. Unlike Sennett, he writes as someone embedded and at home with a craft. He is concerned with learning – what does the process of making things reveal to us about ourselves? It is less a performance than a journey: ‘As a maker, you put one foot in front of the other and you own the journey’ (Korn 2015: 104).

Second, as D. D. Guttenplan (2008) has commented, while Sennett ‘leaps back and forth across the gap between practice and theory with great agility’, he does not slow down enough to develop a thesis. This would be about, according to Guttenplan, ‘the links between the patient learning required to master a skill (or play, a set of scales) and the forbearance required for political or social cooperation’. Interestingly, the latter was an area that Sennett turned to for his next book.

Third, there is the question of whether Sennett makes his argument against Arendt stand up. He had ‘sought to rescue Animal laboreus from the contempt with which Hannah Arendt treated him’ (2008 286). Arendt’s treatment of Animal laboreus was grounded in a respect for hermeneutic enquiry but it is open to questioning. As Maurizio Passerin d’Entreves (2019) has argued, her concept of the social ‘blinds her to many important issues and leads her to a series of questionable judgments’. However, the careful steps to make such a case is not the route that Richard Sennett takes here.

Cooperation

Cooperation takes the familiar Sennett route of drawing upon examples and discussion, and then developing a range of general points and suggestions. This is not a focused empirical study, nor does it have any ambition to engage fully with, or seek to develop, social, economic and political theory. It does not explore in meaningful ways how economic and political forces impact on our disposition or capacities to cooperate (Maravelias 2012). ‘As a philosopher’, Richard Sennett says, ‘I’m interested … in that fraught, ambiguous zone of experience where skill and competence encounter resistance and intractable difference’ (2012: 8-9). As such, and in the way we have come to expect from Sennett, the book raises some interesting areas for exploration.

Sennett explores cooperation as a craft. It entails ‘the skill of understanding and responding to one another in order to act together, but this is a thorny process, full of difficulty and ambiguity and often leading to destructive consequences’ (2012: 7). His focus is on ‘responsiveness to others, such as listening skills in conversation, and on the practical application of responsiveness at work or in the community’ (op. cit.). Often, we do not recognize what we need from others or what they want (or ought to want) from us. He argues that the ‘most important fact about hard cooperation is that it requires skill’. Sennett then goes on to say that Aristotle defined skill as ‘techné, the technique of making something happen, doing it well’. From there, Sennett argues that responsiveness is less an ethical disposition (as Michael Ignatieff suggests) but ’emerges from practical activity’ (Sennett 2012: 16).

There are some problems with this approach – but I just want to focus on one. Aristotle approaches technê (craft) as a virtue and places it alongside another – phronêsis (practical wisdom). As Richard Parry (2020) has pointed out Aristotle ’emphasizes the former, a disposition (hexis) with respect to making (poiêsis), is distinct from the latter, a disposition with respect to doing (praxis)’. It is not clear what Sennett means by ‘practical action, but two points need to be made. First, Aristotle makes disposition a central concern. Second, it could well be that cooperation arises from the act of doing (praxis) rather than (or as well as) making (poiêsis). In other words, practical wisdom, rather than craft, might be important. The ‘most important point’ could well be that cooperation is an action that it is informed and committed (praxis). It entails doing and thinking and being guided by an ethical disposition.

Sennett’s exploration of cooperation emphasizes the need to make it more open. He frames this via a comparison between dialectic and dialogical conversation. In the former, ‘the verbal play of opposites should gradually build up to a synthesis’; in the latter (after the work of Mikhail Bakhtin) ‘through the process of exchange people may become more aware of their own views and expand their understanding of one another’ (Sennett 2012: 37). He argues that dialogic cooperation is central as it ‘entails a special kind of openness, one which enlists empathy rather than sympathy in its service’ (op. cit.: 202). Sennett then proceeds, initially, to explore its relation to solidarity, to competition and ritual. Some key points appear concerning the first around the tensions between top-down and ground-up orientations.

Top-down politics faces special problems in practising cooperation, revealed in the forming and maintenance of coalitions; these often prove socially fragile. Solidarity built from the ground up strives for cohesion among people who differ… The social bonds forged from the ground up can be strong, but their political force is often weak or fragmented. (op. cit.).

There also obvious tensions between cooperation and competition. Sennett argues that modern capitalism has unbalanced them and ‘made cooperation itself less open, less dialogic’. (op. cit.: 204)

In the second part of the book, we turn to the weakening of cooperation through growing inequality, changes in the social triangle and ‘the uncooperative self’. The social triangle discussion returns to Sennett’s work with John Cobb (1972) and the relationships they found workers forming. These comprised of three elements: earned authority, mutual respect and cooperation during a crisis (2012: 231). He argues that ‘finance capitalism’ has weakened the triangle and the social bonds it forges. The experience of growing structural inequality and new forms of labour has psychological consequences.

A distinctive character type is emerging in modern society, the person who can’t manage demanding, complex forms of social engagement, and so withdraws. He or she loses the desire to cooperate with others. This person becomes an ‘uncooperative self’. (2012: 278)

These discussions contain some important points and questions but become more speculative as this part of the book progresses. At one level this is not a bad thing, but to get away with it you require much stronger links into empirical work and critique or use of established theory.

The final three chapters look at how cooperation can be repaired and strengthened. Initially, Sennett returns to some of the concerns of The Craftsman, arguing that ‘the processes of making and repairing inside a workshop connect to social life outside it’. (2012: 339). He then moves on to ‘everyday diplomacy’ and the heritage in ordinary life. The last chapter turns to the challenges of strengthening cooperation within local communities – especially those ‘whose economic heart is weak’ (2012: 390). The problem is that there is little concrete suggestion or discussion of current activity and practice. Instead, we are treated to snatches of Freud and Durkheim, talk of vocation, and discussion of simple community and the pleasures of community. As Jenny Turner (2012) in her review of the book put it, ‘what exactly is Sennett talking about?’

Building and dwelling

Across the water from the City: social housing to expensive apartments and the financial centre of London. A picture from the top of a tower block managed by a housing cooperative.

For this final book in the series, Richard Sennett returns to one of his central concerns – the experience and nature of urban spaces and, in particular, cities. His approach remains the same but where he says he writes ‘within a long-standing tradition, that of American pragmatism’ in The Craftsman (2008: 13), as a philosopher in Together, here he is the flaneur, planner and teacher. Previously, we looked at Sennett the historian, Sennett the sociologist, and Sennett the public intellectual. Here, we have Sennett the urbanist – and in many senses, this is his home territory. He grew up and has made homes in cities, written a series of books exploring city life (see, in particular, 1970b, 1991, 1994 and 2018), worked as a planner, and has been a consultant for ‘various bodies of the United Nations, mostly concerning public space’ (Sennett 2019a).

Urbanists, as Johnathan Meades (2018) has commented, tend to use language that is only understood by themselves and, quoting the Dutch architect Reinier de Graaf, are “united through the frank admission that we do not have a clue”. Luckily Sennett does not conform to this.

Despite a few uncomfortable instances of “outside the box”, “world-class city” and “tipping point” (which pace Richard Sennett is hardly “everyday language” save among the lexically deprived), Building and Dwelling is pretty much jargon-free, quite an achievement given the milieu the author evidently frequents. It is, too, far from clueless. (Meads 2018)

The book puts ‘Homo faber in the city’ (Sennett 2018: 55). Central to the approach is the distinction made between ville and cité (2018: 12). ‘City’ is taken as having two different meanings – ‘one a physical place [ville], the other a mentality compiled from perceptions, behaviours and beliefs [cité]’. Cité is both the characteristics of a local way of life and a kind of consciousness. To appreciate what is happening here, Sennett uses three notions:

Crookedness. Sennett argues that in the twentieth century, cité and ville ‘turned away from each other in the ways that urbanists thought about and went about city-making. Urbanism became, internally, a gated community’ (2018: 27). He argues that cities are crooked because they are diverse: with many migrants speaking dozens of languages, glaring inequalities and the stresses of everyday living. He askes whether the physical ville can make good such difficulties? ‘The city seems crooked in that asymmetry afflicts its cité and its ville’ (op. cit.: 18).

Openness. Sennett approaches cities as open rather than closed systems. They contain large, complex networks that do not have simple rules of operation or central control. To understand them you have to view them as a whole. Their diverse nature, he suggests, also requires an open society based on liberal values (after Popper 1945). The problem is, of course, that modern capitalism tends to look for closure rather than openness (Sennett 2019a).

Modesty. Here Sennett returns to Homo faber and the need to practise a certain kind of modesty as urbanists:

… living one among many, engaged by a world which does not mirror oneself. Living one among many enables, in Robert Venturi’s words, ‘richness of meaning rather than clarity of meaning’. That is the ethics of an open city. (2018: 776)

In the book, Sennett looks how the urbanism has evolved – and the contribution of key urban theorists such as the Chicago School, Lewis Mumford and Jane Jacobs; influential planners such as Haussmann for Paris, Cerdà for Barcelona, Olmsted in New York; and turns to Weber and others for a more sociological understanding. He also explores issues arising from the gap between the lived and the built. These include the effects of the huge growth of cities in the Global South, the impact of changing technologies and working with cultural difference. As he recognizes, the scale of change and responses required rather mean that the small, incremental processes favoured by Jane Jacobs and, previously, Sennett himself have to be added to. Sennett makes an argument for co-production of plans and increased cooperation involving planners, local communities, political interests etc. As Rowan Moore (2018) has pointed out, he doesn’t ‘propose much by way of what these larger plans might be’.

He thrives more when making sharp and nuanced observations of the ways people live in cities, which perform the vital service of puncturing the fuzzy cliches that tend to grow around notions like “tolerance” and “diversity”. (op. cit.)

From there Sennett looks to what cities could be like if they were more open. The inhabitants of such cities have to develop the capacity to deal with and manage complexity. He argues that an open ville is marked by five forms which allow the cité to become complex.

Public space promotes synchronous activities.

It privileges the border over the boundary, aiming to make the relations between parts of the city porous.

It marks the city in modest ways, using simple materials and placing markers arbitrarily in order to highlight nondescript places.

It makes use of type-forms in its building to create an urban version of theme and variations in music.

Finally, through seed-planning the themes themselves – where to place schools, housing, shops or parks – are allowed to develop independently throughout the city, yielding a complex image of the urban whole.

An open ville will avoid committing the sins of repetition and static form; it will create the material conditions in which people might thicken and deepen their experience of collective life. (Sennett 2018: 627) [I have broken up the original paragraph into five points and a comment.]

The final section returns to the essential crookedness of the city.

As a result of these efforts, this book stands apart from most of what Richard Sennett has previously written. Yes, it has the same dives into history, sharp insights and observations, and links into his life and friendships – but given the scale and complexity of its subject matter and the peculiarities of ‘the city’ industry, this book moves well beyond the essay format. It also builds on the previous two books and becomes, in some ways, a manifesto for open systems, cooperation and a certain kind of modesty. Crucially, what Sennett has also created is a text for people wanting to shape and develop their thinking about urbanism.

Conclusion

According to the writer Marina Warner, Richard Sennett has a great ability to re-invent himself (Benn 2001). As we have seen, he does tend to take on different personae in his books. His philosophical orientation alters too, as Boyd Tonkin comments:

In a previous interview, Sennett described himself to me as “an old-fashioned humanist and, I suppose, an old-fashioned democratic socialist”. Now he adds to this profession of lightly-worn faith an intellectual calling-card: “I am a pragmatist. That’s my philosophical church.” “The pragmatist movement from [William] James and [John] Dewey to Richard Rorty, Amartya Sen and myself is about discovering what people are capable of doing,” he explains. “It tries to understand social injustice and oppression by finding something positive that has been suppressed.” (Tonkin 2008)

There are some pretty constant themes in Sennet’s work around class, capitalism, craft and the city – and he has produced important and thought-provoking essays over five decades. Of particular note here are The Uses of Disorder, Authority, and Respect in a World of Inequality. In The Hidden Injuries of Class (with Jonathan Cobb) and The Corrosion of Character, he has added considerably to our appreciation of the experiences of working-class employees within new forms of capitalism. Sadly, by staying with the essay form and choosing not to engage in sustained and focused theory-making there have been some missed opportunities – especially with the Authority – Corrosion – Respect series where this could have led to a major contribution to thinking around the experience and nature of power. The next series – The Craftsman – Together – Building and Dwelling – looked like it might head the same way but was saved by the last book and by Richard Sennett’s disposition as an urbanist. It pointed to ways in which the discourses around urbanism could develop. More importantly in some ways, it is a thought-provoking text and would make for a great series of undergraduate lectures. That is just about the highest compliment one can currently make in the light of the abject failure of many academics and most universities to attend to the needs of their students.

References

Arendt, H. (1951|2017) The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich | London: Penguin Classics. (Page numbers refer to the 2017 epub version).

Arendt, H. (1958|1998) The Human Condition. 2e. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Page numbers refer to the 1998 epub version).

Arendt, H. (1963|2006). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Viking Press, 1963. Revised and enlarged edition, 1965 | London: Penguin 2006).

Arendt, H. (2002). Vita activa oder Vom tätigen Leben. Munich: Piper.

Bakhtin, M. (2004). The Dialogic Imagination, trans. C. Emerson and M. Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bauman, Z. (1982). Review of Authority by Richard Sennett, Theory, Culture and Society 1(2). [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/026327648200100216. Retrieved June 21, 2019]

Benn. M. (2001). Intercity scholar, The Guardian February 3. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/feb/03/books.guardianreview4. Retrieved February 27, 2020].

Bergson, H. (1907). L’e?volution creatrice. Paris: Felix Alcan.

de Botton, A. (2003) The deserving poor, Daily Telegraph January 25. [https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/4729746/The-deserving-poor.html. Retrieved March 4, 2020].

Carr, E. H. (1961). What is History? London: St. Martin’s Press.

d’Entreves, M. P. (2019). Hannah Arendt, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). [https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/arendt/. Retrieved November 21, 2019]

Evans. R. J. (1999). In Defense of History. New York; W. W. Norton and Co.

Feeney, M. (2011). Obituary: Oscar Handlin; historian led US immigration study, The Boston Globe September 22. [http://archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/obituaries/articles/2011/09/22/oscar_handlin_historian_led_us_immigration_study/. Retrieved February 29, 2020].

Feldman, D. et. al. (2019). Understanding how millennials engage with causes and social issues. Achieve/The Case Foundation. [http://www.themillennialimpact.com/sites/default/files/images/2018/MIR-10-Years-Looking-Back.pdf. Retrieved March 19, 2020].

Foucault, Michel (1966 | 1970). Les Mots et les choses: Une achéologie des sciences humaines | The Order of Things. Paris: Gallimard | New York: Pantheon/Random House.

Foucault, Michel (1975 | 1979). Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison | Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Alan Sheridan (trans.). Paris: Gallimard | New York: Vintage.

Foucault, M. (2000). Interview with Michel Foucault in J.D. Faubion (ed.) Power: Essential Works Of Foucault, 1954-1984. New York: The New Press.

Foucault, M. and Sennett, R. (1981). Sexuality and solitude, London Review of Books 3 (9) May 21, 1981. [https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v03/n09/michel-foucault/sexuality-and-solitude?referrer=. Retrieved: March 27, 2020].

Frisch, M. (1957 | 2006). Homo Faber. Ein Bericht.Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag. | Homo Faber. A report. Trans. M. Bullock. London: Penguin Modern Classics.

Goodman, P., & Goodman, P. (1960a). Communitas: Means of livelihood and ways of life. New York: Knopf. (First published in 1947).

Goodman, P. (1960b). Growing up absurd: Problems of youth in the organized society. New York: Vintage Books.

Goodman, P. (1964). Compulsory miseducation and the community of scholars. New York: Vintage Books.

Goodman, P. (1977). Drawing the line: The political essays of Paul Goodman. New York: Free Life.

Gopinath, M. (2015). The 5 Truths that Define Millenials. London: Ipsos. [https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/2016-08/5_truths_that_define_Millennials.pdf. Retrieved March 19, 2020].

Gorman, T. J. (2017). Growing up Working Class: Hidden injuries and the development of angry white men and women. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Green, D. (2015). The 20-year battle to demolish Chicago’s notorious Cabrini-Green housing project, CityMetric, November 15. [https://www.citymetric.com/skylines/20-year-battle-demolish-chicago-s-notorious-cabrini-green-housing-project-1575. Retrieved February 27, 2020].

Guttenplan, D. D. (2008). Routine glories. A review of Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman, Times Literary Supplement May 16 2008 page 16.

Harvard University (2017). 2017 Centennial Medalist Citations. [https://gsas.harvard.edu/news/stories/2017-centennial-medalist-citations. Retrieved February 29, 2020].

Horowitz, I. L. (1983) C Wright Mills An American Utopia. New York: The Free Press.

Ignatieff, M. (1986). The Needs of Strangers. London: Penguin.

Illich, I. (1970). Deschooling society. New York: Harper & Row.

Illich, I. (1969). Celebration of awareness: A call for institutional revolution. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Illich, I. D. (1973). Tools for conviviality. New York: Harper and Row.

Illich, Ivan (1974) Energy and Equity, London: Marion Boyars.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of American Cities. New York: Random House.

Jencks, C., & Riesman, D. (1968). The academic revolution. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Knott, M. L. (2014). Unlearning with Hannah Arendt trans. D. Dollenmayer. London: Granta.

Koepke, W. (1991). Understanding Max Frisch. Columbia SC.: University of South Carolina Press.

Korn, P. (2015). Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman. London: Square Peg | Vintage Books.

Lawler, L. (2016). Henri Bergson, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bergson/. Retrieved April 2, 2020]

Lipset, S. M., & Lowenthal, L. (eds.) (1962). Culture and social character: The work of David Riesman reviewed. New York, Free Press of Glencoe.

Lukes, S. (1974). Power. A radical view. London: Macmillan.

Lukes, S. (2005). Power. A radical view. 2e. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Macfarlane, A. (2009). An interview with the sociologist Richard Sennett, University of Cambridge Video and Audio Collections. [https://www.sms.cam.ac.uk/media/1130356?format=mpeg4&quality=360p. Retrieved: February 29, 2020].

Mann, M. (2013). The Sources of Social Power. Volume 4: Globalizations 1945-2011. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press.

Maravelias, C. (2012). Review of Richard Sennett’s Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation. Dans M@n@gement 2012/3 (15) pp. 344 – 349. [https://doi.org/10.3917/mana.153.0344. Retrieved March 3, 2019].

Meades, J. (2018). Review of Richard Sennett’s Building and Dwelling, The Guardian Feb 24. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/24/building-and-dwelling-richard-sennett-review. Retrieved September 12, 2019].

Mills, C. Wright (1951) White Collar. The American Middle Classes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mills, C. Wright (1956) The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mills, C. Wright (1958a) The Causes of World War Three. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Mills, C. Wright (1958b) ‘The structure of power in American society’, British Journal of Sociology IX(1). Reproduced in Mills, C. Wright (1963) Power, Politics and People. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mills, C. Wright (1959) The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mills, C. Wright (1960) Listen Yankee: The revolution in Cuba. New York: McGraw Hill.

Mills, C. Wright (1963, 1967) Power, Politics and People. The collective essays of C. Wright Mills. Edited by Irving H. Horowitz. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moore, R. (2018). Review of Richard Sennett’s Building and Dwelling, The Guardian Feb 19. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/19/building-and-dwelling-by-richard-sennett-book-review-architecture-rowan-moore. Retrieved: April 12, 2020].

New York University Archives (2019) Guide to the Records of The New York Institute for the Humanities RG.37.4, New York University Archives. [http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/archives/nyih/bioghist.html. Retrieved February 27, 2020].

Parry, R. (2020). Episteme and Techne, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.). [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/episteme-techne/. Retrieved April 8, 2020].

Popper, K. (1945 | 2011) The Open Society and its Enemies. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul | Abingdon: Routledge Classics.

Riesman, D., Glazer, N. and Denney, R. (1950). The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sassen, S. (1988). The Mobility of Labor and Capital. A Study in International Investment and Labor Flow. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sassen, S. (1991). The Global City. New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton NJ.: Princeton University Press.

Sassen, S. (1999). Globalization and its discontents. New York: New Press.

Sassen, S. (2006). Territory, Authority, Rights: From Medieval to Global Assemblages. Princeton NJ.: Princeton University Press.

Sennett, Richard (1970a). Families Against the City: Middle-Class Homes of Industrial Chicago, 1872-1890. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sennett, Richard (1970b | 1973). The Uses of Disorder. Personal identity and city life. New York: Knopf. | Harmondsworth: Pelican Books.

Sennett, Richard and Cobb, Jonathan (1972). The Hidden Injuries of Class. New York: Knopf.

Sennett, Richard (1977). The Fall of Public Man. On the social psychology of capitalism. New York: Knopf.

Sennett, Richard (1980). Authority. New York: Knopf.

Sennett, Richard (1982). The Frog who Dared to Croak. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Sennett, Richard (1984). An Evening of Brahms. New York: Knopf.

Sennett, Richard (1987). Palais-Royal. New York: Knopf.

Sennett, Richard (1991). The Conscience of the Eye. The design and social life of cities. New York: Knopf.

Sennett, Richard (1994). Flesh and Stone: The body and the city in western civilization. New York: W.W. Norton

Sennett, Richard (1998). The Corrosion of Character: The personal consequences of work in the new capitalism. New York: W.W. Norton

Sennett, Richard (2003). Respect in a World of Inequality. New York: W.W. Norton

Sennett, Richard (2006). The Culture of the New Capitalism. New York: W.W. Norton

Sennett, Richard and Calhoun, Craig (eds.) (2007). Practising Culture. Abingdon: Routledge.

Sennett, Richard (2008). The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sennett, Richard (2011). The Foreigner. Two essays on exile. London: Notting Hill Editions.

Sennett, Richard (2012). Together: The rituals, pleasures, and politics of cooperation. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Page numbers refer to the epub version of the book].

Sennett, Richard (2018). Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City. London: Allen Lane. [Page numbers refer to the epub version of the book].

Sennett, Richard (2019a) The fight for the city, Eurozine February 14. [https://www.eurozine.com/the-fight-for-the-city/. Retrieved: April 8, 2020].

Sennett, R. (2019b). The Narratives of Homo Faber. Conversation between Richard Sennett and Carles Muro, Public Space March 20. [https://www.publicspace.org/lectures/-/event/the-narratives-of-homo-faber. Retrieved February 27, 2020].

Smith, M. K. (1999, 2009, 2019) ‘C. Wright Mills: power, craftsmanship, and personal troubles and private issues’ The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/c-wright-mills-power-craftsmanship-and-private-troubles-and-public-issues/. Retrieved: March 31, 2020].

Smith, M. K. (2019). Haltung, pedagogy and informal education, infed.org. [https://infed.org/mobi/haltung-pedagogy-and-informal-education/. Retrieved: April 6, 2020].

Station, E. (2011). Life in practice. In his latest book, sociologist Richard Sennett, AB’64, explores the social craft of cooperation, The University of Chicago Magazine November/December. [https://mag.uchicago.edu/law-policy-society/life-practice#. Retrieved February 27, 2020].

Taylor, Dianna (2014). Introduction: Power, freedom and subjectivity in Dianna Taylor (ed.) Michel Foucault. Key concepts. Abingdon: Routledge.

Theatrum Mundi (undated) About, Theatrum Mundi. [https://theatrum-mundi.org/about/. Retrieved February 27, 2020]

Tonkin, B. (2008). Richard Sennett: Back to the bench, The Independent February 8. [https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/richard-sennett-back-to-the-bench-779345.html. Retrieved February 27, 2020].

Turner, J. (2003). Integrity rules, The Guardian January 25. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/jan/25/featuresreviews.guardianreview2. Retrieved March 2, 2020].

Turner, J. (2012). Superficially pally. Review of Richard Sennett’s Together: The rituals, pleasures, and politics of cooperation, London Review of Books (34): 2, March 22, 2012. [https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v34/n06/jenny-turner/superficially-pally. Retrieved: January 5, 2019].

Wachtel, E. (2013). An Interview with Richard Sennett, Brick. [https://brickmag.com/an-interview-with-richard-sennett/. Retrieved February 27, 2020].

Zorbaugh, H. W. (1929) The Gold Coast and the Slum: A Sociological Study of Chicago’s Near North Side. Chicago Ill.: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgements: Images: Richard Sennett 2016 – Deutsche Bank | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence.

The Cabrini Green public housing project in Chicago by Jet Lowe | Wikimedia PD.

Portrait of Hannah Arendt on a wall in the courtyard of her birthplace at Lindener Marktplatz 2, on the corner of Falkenstraße, in the district of Linden-Mitte. The picture was reproduced from a photograph by Käthe Fürst (Ramat Ha Sharon, Israel. The artwork is a commissioned work by the Hanoverian graffiti artist Patrik Wolters aka BeneR1 in August 2014 in teamwork with Kevin Lasner aka koarts … Wikimedia – ccasa3 licence.

The picture of the City and the west of Bermondsey Picture: Bermondsey west is by sarflondondunc | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2020). Richard Sennett: Class and the new capitalism, craftsmanship, cooperation and cities, infed.org. [https://infed.org/mobi/richard-sennett-class-the-new-capitalism-craftsmanship-cooperation-and-cities/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K Smith 2020

ery; that the current organization of city communities encourages men to enslave themselves in adolescent ways; that it is possible to break through this framework to achieve an adulthood whose freedom lies in its acceptance of disorder and painful dislocation; that the passage from adolescence to this new, possible adulthood depends on a structure of experience that can only take place in a dense, uncontrollable human settlement—in other words, in a city.

ery; that the current organization of city communities encourages men to enslave themselves in adolescent ways; that it is possible to break through this framework to achieve an adulthood whose freedom lies in its acceptance of disorder and painful dislocation; that the passage from adolescence to this new, possible adulthood depends on a structure of experience that can only take place in a dense, uncontrollable human settlement—in other words, in a city.