Walking in central London we can find many places associated with key figures and moments in the making of informal education. Explore them through a virtual (or real) walk based on Charles Booth’s famous poverty map.

The walk starts on the bottom right of the map (next to Charing Cross Station) and makes its way northwards via The Strand, Covent Garden, Trafalgar Square, Soho and ends close to Tottenham Court Road Underground Station.

Click on the link below to the digital version of Booth’s Map prepared by the London School of Economics. Copy the link, then open a new window in your browser and paste it in. You can also toggle between it and a modern street map. Swap to the other browser window for a briefing on each of the stops.

Click to access Booth’s Map

Click to download a PDF version of the walk

______

The walk: Embankment • The Strand • Covent Garden • Trafalgar Square • St Martin’s Lane and Five Dials • Soho and Chinatown • Greek Street and Soho Square • Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road • References • How to cite this piece

Our walk begins on the Embankment. It then winds its way through Trafalgar Square, Covent Garden, Soho and Bloomsbury. As well as taking in some of the key buildings and places associated with the development of informal education – we can also see Covent Garden Market, and Chinatown.

We see:

- the site of some early street work.

- a pioneering club and hostel for girls.

- one of the first working men’s clubs.

- early examples of schools, settlements and colleges.

- examples of early popular education – libraries, coffee houses, and bookshops.

We learn about some of the key figures – Maud Stanley and girls work; Baden Powell and Scouting; Albert Mansfield and adult education; Lily Montagu and Jewish youth work; and George Williams and the YMCA

The Embankment

We start close by the river at The Embankment and our route takes us through Covent Garden and Soho. On our way, we find a stunning range of informal education activities.

Nearest Underground Station – The Embankment: Bakerloo, Circle, District and Northern lines. (Nearest national rail station: Charing Cross).

The Embankment to The Strand: Leave The Embankment Station by the northern (or left-hand from the trains) exit. Ahead you will see Villiers Street, and further down – on your left – the entrance to the Victoria Embankment Gardens. Make your way around the Bandstand (on your left). Straight ahead you should see The York Watergate. Walk around the lefthand side of the Watergate (on your left you will see a commemoration of Sir Joseph Bazalgette. Continue around and up the steps to Buckingham Street (behind the Watergate).

[Wheelchair users will need to go up Villiers Street (on your right you will see a blue plaque on number 43 where Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) lived. Towards the top of the street turn right into John Adam Street. Buckingham Street is on your right.]

The Victoria Embankment was built as part of Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s work as Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board. Completed in 1870, a substantial amount of land was reclaimed from the river. First proposed by Christopher Wren after the Great Fire, it allowed the creation of a new thoroughfare and gardens, as well as creating better river defences and sewage arrangements. The scale of the development can be seen from the position of the York Watergate (1626) – the river steps to York House (built sometime before 1237 for the Bishops of Norwich and later the home of the Duke of Buckingham, and demolished in the 1670s). Francis Bacon, the philosopher, essayist and statesman was born at York House in 1561.

Buckingham Street lies ahead of you. On your left, you will see plaques commemorating Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), the diarist and Secretary of the Admiralty. He lived first at Number 12 (1679-1688) and then at Number 14.

On your right Number 15 was the site of a house where Charles Dickens (1812-70) had rooms on the top floor in 1833. Previous occupants of the house include Peter the Great (1698) and Henry Fielding (1735). Samuel Taylor Coleridge lived at Number 21 (1799).

Charles Dickens and popular education, 15 Buckingham Street. While living in Buckingham Street, Dickens worked as a reporter for the Morning Chronicle. He had taught himself shorthand, worked as a court reporter (at age 16) and later joined the staff of the Mirror of Parliament (a paper that reported Parliamentary proceedings). He had begun to take ‘writing’ seriously. His first short story, ‘A Dinner at Poplar Walk’ (published under the name of Boz) appeared in the Monthly Magazine. He was later to use his experience of the street – placing David Copperfield in a set of chambers at No. 15 (David Copperfield was published in 1849-50).

The area was hardly new to him. When his father’s debts had landed him and the rest of the family in Marshalsea Prison, Charles Dickens had been put to work nearby at Warren’s Blacking Factory at 30 Hungerford Stairs. (Hungerford Stairs were 100 metres upriver under what is now Charing Cross Station). He was paid six shillings a week wrapping boot-blacking bottles. The factory was in a house at the bottom of the stairs, next to the river.

Dickens is of particular significance as an exemplar of a writer who is concerned with popular education or what James Hole (1860) described as social education – the educative power of newspapers, novels and various forms of entertainment. Here we highlight three aspects. First, there is the obvious impact of his novels. He provided his contemporaries with vivid accounts of daily life – particularly of those living in poverty. Second, there are Dickens’ efforts to facilitate self-education through the publishing of the publishing of a weekly journal Household Words (1850-59) and All Year Round (1859-70). Third, we need to note his campaigning activities around education. His harrowing accounts of schooling in Nicholas Nickleby (1838-9) and Hard Times (1854); his encounters with ragged schooling (one visit to Field Lane School, Saffron Hill resulted in A Christmas Carol 1843); and his public speaking, for example, in the cause of adult educational reform are examples of this. [For more on these see our piece on Charles Dickens].

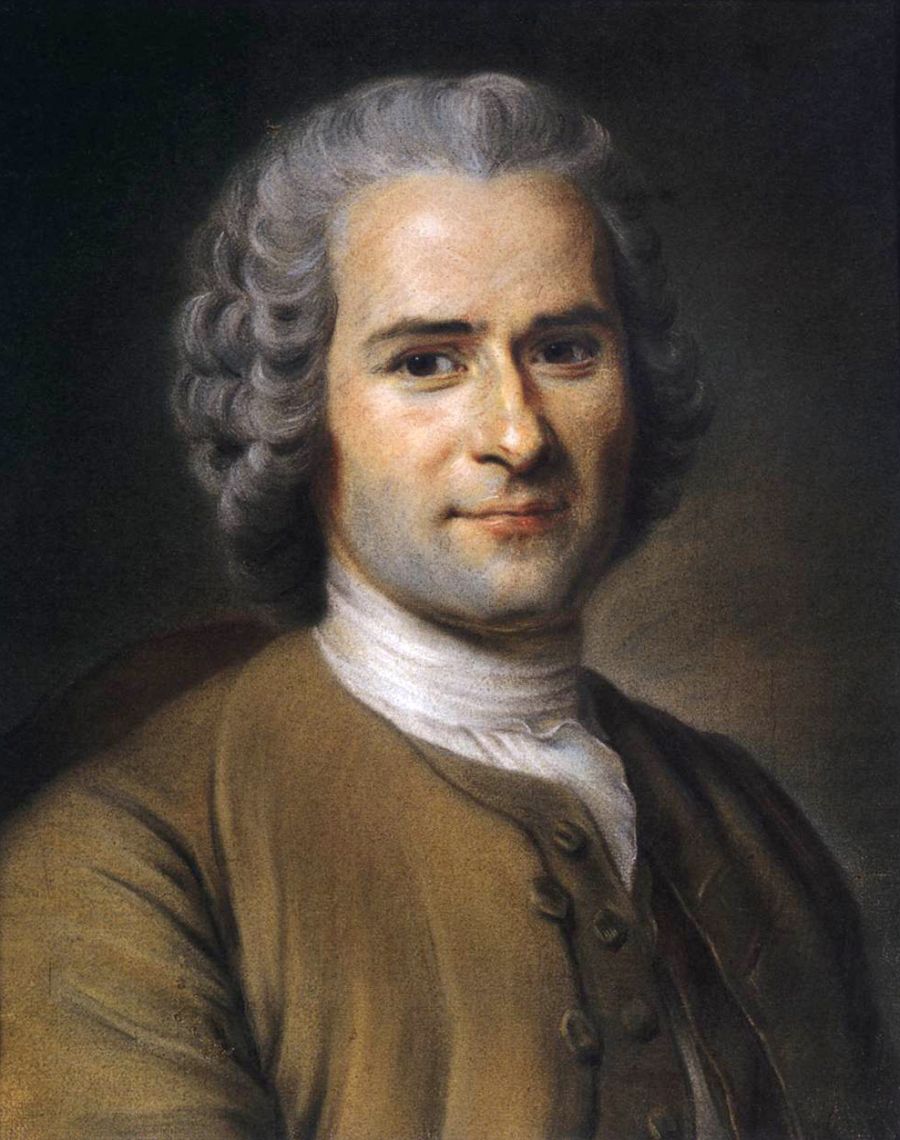

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, nature and education, 10 Buckingham Street WC2. Rousseau (1712-1778) has been described as one of the most significant writers on education since Plato. The scale of his contribution is indicated by Darling (1994) when he argued that the history of child-centred educational theory is a series of footnotes to him. His great work on education, Émile, drew on thinkers that had preceded him – for example, John Locke on teaching – but he was able to pull together strands into a coherent and comprehensive system – and by using the medium of the novel he was able to dramatize his ideas and reach a very wide audience. He made, it can be argued, the first comprehensive attempt to describe a system of education according to what he saw as ‘nature’. His thinking certainly stresses wholeness and harmony, and a concern for the person of the learner (see our piece on Jean-Jacques Rousseau).

Rousseau had a fundamental dislike of England and the English – but he was prevailed upon to live in England following the reaction to the publication of The Social Contract and Émile in late 1765. He arrived in January 1766 accompanied by his little dog Sultan and spent some 18 months in England. He was invited and accompanied to England by David Hume (1711-1776), the Scottish philosopher (perhaps best known for his Treatise of Human Nature – first published in 1740). Initially, Rousseau lived in rooms found by Hume at 10 Buckingham Street, London in 1766. However, he hated London as it was full of ‘black vapours’ (Edmonds and Eidinow 2006). He soon moved out to Chiswick, and then to Hume’s home at Wootton Hall in Staffordshire.

While in England, Rousseau was, in Robert Wokler’s (1995: 14) words, ‘overwhelmed by suspicions of an international conspiracy to discredit his character, managing to bring great misery upon himself, and much discomfort for Hume. Real persecution compounded the paranoia with which he was undoubtedly afflicted… for the rest of his life. While here he started work on, and probably completed, Part One, of The Confessions. The book is ‘an important reference point in the history of literature’ (Matravers 1996: viii-ix). Rousseau took autobiography beyond the introspection of St. Augustine by ‘tracing the casual aspects of his character back to incidents in his childhood’ (op. cit.).

Charity Organisation Society and social work, 15 Buckingham Street. Founded in 1869, the Charity Organization Society (COS) made a deep impact on social work in Britain through its advocacy and codification of emerging methods. This, with its focus on the family, and upon a scientific approach provided a key foundation for the development of social work as profession in Britain.

The Charity Organization Society came into being in large part as a response to the competition and overlap occurring between the various charities and agencies in many parts of Britain and Ireland. The general lack of cooperation between organizations not only led to duplication, it also involved what was seen at the time as indiscriminate giving. Not enough detailed attention was given to examining the claims and needs of potential clients. The Society had its first offices at 15 Buckingham Street.

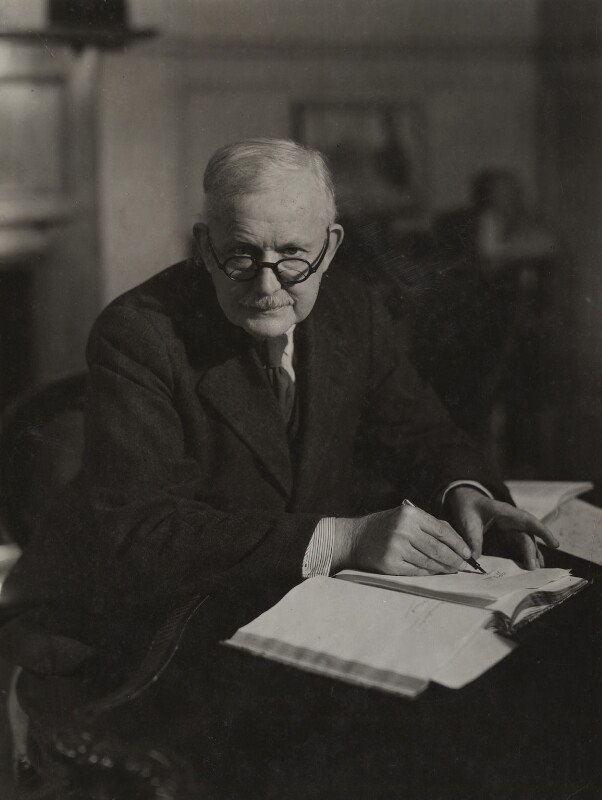

Albert Mansbridge (1876-1952) and the Workers’ Educational Association, 24 Buckingham Street. Albert Mansbridge was a key figure in the development of adult education in Britain. In many respects, he was a classic example of working-class self-education. He became involved in the developing adult education movement – in part through the Cooperative Movement, and also through the developing university extension movement and argued for change (see Jennings 2002: 18). ‘[C]heered on’ by his wife Francis (Mansbridge in Harrison 1959: 262), he, decided in his words, ‘to take action by becoming the first two members of “An Association to Promote the Higher Education of Working Men,” and at that symbolic meeting by democratic vote I was appointed Hon. Secretary pro tem)’ (Mansbridge 1920: 11-12). The Workers’ Educational Association as it became known two years later, looked to deepen working class involvement in education beyond the ‘hard veneer’ of elementary education (Mansbridge 1944: 1-12). It set its sights on ‘university standards’ and saw voluntary and democratic organization as its means (see adult education and Toynbee Hall).

The first office of the new Association was the Mansbridges’ home in Ilford. It moved to two small rooms at 24 Buckingham Street in 1907 (and then on to Adam Street and to 14 Red Lion Square) (Jennings 2002: 73). The need for increased space (which spurred these moves) was a reflection of the growth of the Association. The first branch was in Reading in 1904; two years later there were 13 branches and 110 by 1912 (Fieldhouse 1996: 170). There were over 900 branches by the end of the Second World War.

Go up Buckingham Street and cross John Adam Street to York Place (this was formely known as Of Lane). The building that Quentin Hogg’s Of Lane ragged school used is no longer there – but we can still get some sense of what the alley was like.

Hogg was later to open the Youth’s Christian Institute (see below) (1870) and to pioneer the Polytechnic movement (following the establishment of the Regent Street Polytechnic in 1882).

Return to John Adam Street and turn left. Up the slope on your right you will see The Adephi. Turn left down Robert Street until it meets Adelphi Terrace.

The Adelphi – the current building was erected in 1938 and replaced a beautiful riverside development of 24 houses built from 1772 on by John, Robert, James and William Adam (Adelphoi is Greek for brothers). Among its occupants were David Garrick (1717-79) at No. 6 Adelphi Terace (1772-79), George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) at No. 10 (1899-1927) and Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) (he worked at No. 8 for Arthur Bloomfield, the architect from 1862 to 1867).

Sunday schooling – Robert Raikes and Hannah More, No.6 Adelphi Terrace and Victoria Embankment Gardens). There is some debate concerning the origins of Sunday Schools. As Sutherland (1990: 126) has commented, Robert Raikes (1735-1811) is traditionally credited as pioneering Sunday Schools in the 1780s; ‘in fact teaching Bible reading and basic skills on a Sunday was an established activity in a number of eighteenth-century Puritan and evangelical congregations’. In Wales, the circulating schools offered one model of such activity (see the development of adult schools). That said, Robert Raikes made a notable contribution to the development of Sunday schooling. Robert Raikes started his first school for the children of chimney sweeps in Sooty Alley, Gloucester (opposite the city prison) in 1780. (In Victoria Embankment Gardens below The Adephi we can find a statue of Robert Raikes. It bears the inscription ‘Robert Raikes. Founder, Sunday Schools 1780. Erected by the Sunday School Union with contributions from grateful teachers and scholars. July 1880’).

This missionary cum social worker, a working class woman drawn from the neighbourhood to be canvassed, was to provide the “missing link” between the poorest families and their social superiors… Given a three month training… in the poor law, hygiene, and scripture, Mrs Ranyard agents sought to turn the city’s outcast population into respectable, independent citizens through an invigoration of family life. (Prochaska 1988: 49)

By 1867 234 Bible women were working in London. They were, effectively, the first group of paid social workers in Britain.

Return up Robert Street and turn right onto John Adam Street. On your left you will see the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, 9 John Adam Street WC2. Founded in 1754 by William Shipley (with Viscount Folkestone and Lord Romney), the Society aimed to ’embolden enterprise, to enlarge science, to refine art, to improve manufacture and to extend our commerce’. It was the first organization set up in Britain with a similar aim. The first meetings of the Society were held over a circulating library just off Fleet Street. Its offices were situated in Covent Garden. In 1774, the Society moved to the present house, built as part of the Adelphi development. By 1762 there were some 2,500 members or Fellows. Joshua Reynolds and Benjamin Franklin were early members. The Society was given a royal charter in 1847 (Prince Albert was its President from 1843 to 1861). In 1908, the Society was granted the right to call itself the Royal Society of Arts. Today, there are some 30,000 fellows.

The Society continues its work today through various schemes and initiatives. In the education field, this currently includes the Campaign for Learning, Opening Minds: education for the 21st Century, Redefining Schooling, and Redefining Work. It also hosted a large initiative seeking to foster better home-school relations.

The London School of Economics, 9 John Street, Adelphi, 10 Adelphi Terrace, then Clare Market and Houghton Street, was founded in 1895 ‘to promote the study and advancement of Economics, Political Science or Political Philosophy, Statistics, Sociology, History, Geography and any subject cognate to any of these’. The School was established thanks to a bequest by Henry Hunt Hutchinson (a member of the Fabian Society). He left instructions to Sidney Webb and four other trustees to dispose of what remained of his estate for socially progressive purposes.

The School began at 9 John Street (opposite the RSA), then moved around the corner to 10 Adelphi Terrace (later the home of George Bernard Shaw). The British Library of Political and Economic Science was founded in 1896 at No. 19. In 1900 the School became part of the University of London. Two years later it moved to Clare Market.

Training for social work and youth work. The first social work training course in the UK was run by the Women’s University Settlement (Blackfriars – now linked to Mary Ward House) (with the Charity Organizations Society). Some women’s settlements followed offering one-year training courses linked to the Charity Organizations Society’s School of Sociology. The School of Sociology was incorporated in 1912 into the London School of Economics. In 1925 the first specialist professional training course for youth work in Great Britain was established. Before this, uniformed organizations had instituted rigorous training programmes for their volunteers, however, no sustained training programme existed for the small, but growing number of full-time leaders and organizers. The first youth leadership course was designed and organized by the National Council of Girls Clubs and the London School of Economics (Evans 1965: 112).

Continue east along John Adam Street and the junction with Adam Street turn left and walk up to The Strand.

The Strand

At the Strand turn right – walking eastwards. Ahead of you in the distance is The Aldwych.

The street, as we know it now, owes much to the work of John Nash (1752-1835) who planned the improvements to the western end carried out in the 1830s. Among its residents have been William Goodwin (1756-1836) (191 The Strand), George Eliot (at No. 142 between 1851 and 1855) and William Blake (3 Fountain Court, 103-4 The Strand). Blake lived here from 1821 until he died in 1827. His rooms were described by a contemporary as ‘a squalid place of but two chairs and a bed’. The building would have been close to where the entrance to the Savoy is now.

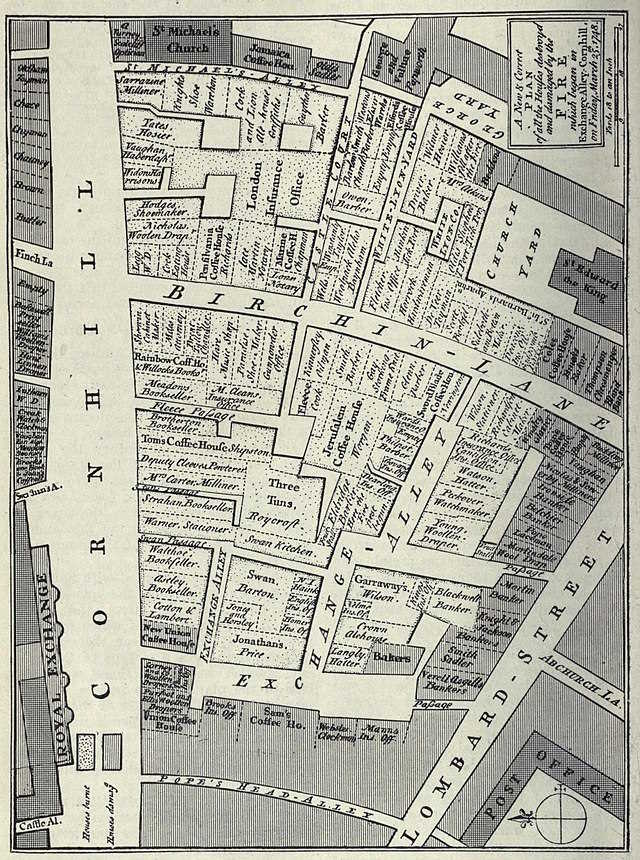

Coffee Houses, The Strand. Coffee houses, as places of news, debate and discussion, played an important part in the general diffusion of knowledge and ideas (Kelly 1970: 82). The first is said to have appeared in Oxford in 1650 and the second in London in 1652. By the turn of the century, there were over 2000 in London alone. As Ellis (1956) puts it, ‘Every trade and every profession had… its favourite meeting place. Sometimes coffee houses were used for more formal educational activities such as lectures, more commonly they provided a base for clubs and societies – including debating clubs. The first of these is supposed to have been based at Mile’s Coffee House, at the sign of the Turk’s Head in New Palace Yard in 1659. William Lovett noted that around a quarter of the 2000 London coffee houses had libraries – some of which had as many as 2000 volumes. Coffee Houses also, traditionally, supplied newspapers for customers to read.

In the eighteenth century, there were several well-known coffee houses on The Strand at the eastern end opposite the law courts. They included the Grecian Coffee House, 19 Devereux Court (which had many members of the Royal Society such as Isaac Newton [1642-1727] as patrons) and Toms.

Opposite the Savoy, on the site now occupied by the Strand Palace Hotel, was Exeter Hall.

Exeter Hall, evangelism and the YMCA, The Strand. Exeter Hall was a famous, nonsectarian hall that hosted many important evangelical meetings and gatherings and that later became part of the YMCA. Built in 1829-31 on what had been the gardens of Exeter House, this building was designed as a hall for religious and scientific meetings and gatherings. It was also to be used by various philanthropic organizations such as the Ragged School Union, the Bible Society, the Anti-Slavery Society, The Temperance Society and the YMCA. The Hall was to have a particular connection to evangelicalism. As well as the organizations and activities already mentioned, many famous preachers such as Charles Spurgeon, could be heard there.

The Hall has a particular place in YMCA history. It represented for George Williams, ‘all that is best in the outside world’. From 1845 for twenty years or more, it was the setting for an annual winter course of lectures (The Exeter Hall Lectures). Attended by very large numbers, these lectures found a much larger audience through publication. When the Hall hit problems, and it looked like it might be turned into a music hall, the lease was purchased by the YMCA (1880). For Williams this was a triumph, for others such as Morley, the Hall was a white elephant that would be a continuing diversion (Binfield 1973: 304). The refitted building opened in April 1881. The large hall was retained but with additional facilities. In the basement, there was a double gymnasium (this was to transfer to a building in Long Acre seven years later). While the building had great symbolic value to the movement and beyond, making full use of it was a problem. It also cost a great deal to maintain. However, it did host some great occasions such as the fiftieth-anniversary celebrations of the YMCA (in 1894) and was the starting point for Williams’ funeral procession on 14th November 1905. For nearly two hours there was an almost continuous line of carriages as far as St Pauls (ibid.: 380).

With changes required by new building regulations and continuing questions of finance and suitability, the decision was taken by the YMCA to leave Exeter Hall and build new premises in Tottenham Court Road. The new Central YMCA was to be a memorial to George Williams. As Binfield (1970: 340) comments, ‘It cannot of escaped shrewd observers that his memorial replaced what many regarded as his most cherished mistake’. Demolition followed in 1907.

Cross the Strand to the northern side (there is a crossing just past the entrance to the Shell building – opposite Southampton Street).

Walk up Southampton Street.

Southampton Street was built between 1706 and 1710 as a residential street. It stayed that way until in the nineteenth century a number of the houses were taken over by newspapers or societies. For example, William Cobbett (1763-1835) published The Porcupine from No. 3. The Strand magazine founded in 1891 by George Newnes (1851-1910) was based at Nos 7-12 (both on your right as you walk up the street). Newnes’ was also famous as publisher of the Sherlock Holmes stories and of P. G. Woodhouse. Another illustrious title published from here was Tit-Bits. (Look out for the wonderful clock designed by Lutyens for the offices).

Stop at the corner of Maiden Lane.

Halfway up Southampton Street, you will see Maiden Lane on your left. This was an old track that went through the convent garden (hence Covent Garden) to St Martin’s Lane. Houses began to be built along it from around 1631. Just down the street on the left is Corpus Christi Catholic Church (1873-4). You can see two ‘blue plaques’ on the street. The first is dedicated to Joseph Turner (1775-1851) the English landscape painter (21 Maiden Lane WC2). He was born here above his father’s barbershop. The second marks Voltaire’s (1694-1778) stay here from 1727 to 1728. He lodged at the White Wig Inn which stood on the site of No.10. Voltaire, (as the plaque says, ‘the French philosopher, playwright and satirist’) had to leave France because of his advocacy of religious toleration and his his attacks on royalty. He had twice been imprisoned in the Bastille. Later he was to have various disputes with Rousseau. Andrew Marvell (1621-78) lived on the site of No. 9 in 1677.

Walk on up to the top of the Street. Ahead you will see Covent Garden.

Covent Garden

Once at Covent Garden. Turn left. Henrietta Street is straight ahead. On your right is an open space where there are often performance artists and the church of St Paul, Covent Garden.

Covent Garden originates from ‘Convent Garden’. It was land owned by the Benedictine Abbot of Westminster that found its way into the hands of the 1st Earl of Bedford in 1550. The fourth earl began to develop Covent Garden in the 1630s. Arcaded terraces were built on the north and east sides of the piazza – and became very fashionable. The fruit and vegetable market was established in the central area in the 1670s. As the market grew, and other fashionable developments appeared westward, the area became rather rundown. The current central market buildings were designed by Charles Fowler and were completed at some expense in 1830.

St Paul – the church facing Covent Garden was designed by Indigo Jones and completed in 1633 as part of the development. It was rebuilt after a fire in the early 1800s (the columns and pillars are from the original building). John Wesley (1703-91) and many other famous preachers have given sermons here. It has a long association with the theatre and you can see a large number of commemorative plaques on its inside walls. Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) set the opening scenes of Pygmalion in the portico facing the market.

Walk down Henrietta Street. This also was a favourite site for publishers including Victor Gollancz (number 14) and Duckworth (number 3)

Go to 33 Henrietta Street WC2 (on your right next to the National Westminster Bank and currently the offices of Hempsons, Solicitors) for Robert Baden-Powell.

Robert Baden-Powell (1857-1941) was an accomplished soldier and first came to wide public notice as the ‘hero of the Siege of Mafeking’. In 1885 he started collecting material for a book on army scouting, which was eventually published in 1899 and, because of his celebrity status, became an instant bestseller. The ideas were seized upon by a number of people working with boys and young men and he was encouraged to write a version for boys. He was also working on his own ideas about education. His concern was that boys should learn to be good citizens (rather than soldiers as some have argued – see Jeal (1989: 365) and that they should learn to act on their own initiative. He placed a special emphasis on adventure, cheerful upbringing (‘children should be brought up as cheerfully and as happily as possible’); and happiness (‘in this life one ought to take as much pleasure as one possible… because if one is happy, one has it in one’s power to make all those around happy’). (From a speech made in 1902 and reported in the Johannesburg Star July 10, 1902 – quoted by Jeal 1989).

In July 1907 he conducted the famous Brownsea Island Experimental Camp. He wanted to test out the ideas he had been working on for a scheme of work for ‘Boy Scouts’. He had completed the first draft of Scouting for Boys. Convinced of his scheme he began a long series of promotional lectures around the country arranged with the YMCA (Reynolds 1942: 147-8). On January 15, 1908, the first part of Scouting for Boys was published. Like modern-day ‘bit-parts’ it appeared at fortnightly intervals (6 parts) priced at 4d each. It quickly appeared in book form (May 1). Sales were extraordinary and quickly groups of young men (and women) were approaching suitable adults to form troupes Springhall 1977). The involvement of Pearson had given the whole enterprise an unedifying commercial edge – and one that was not to profit the Scouts. Baden-Powell had unwisely entered into a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ with him. Considerable efforts were thus made to set up a separate organization and to limit the publisher’s power. The headquarters moved to 116-188 Victoria Street SW1 – but the popular journal The Scout continued to be published out of this office.

Scouting for Boys was also read and taken up by a significant number of middle-class girls on a self-organized basis (Kerr 1936: 16). In September 1908 at Crystal Palace the first big rally was held with some 10,000 Boy Scouts as well as a number of self-organized Girls Scouts attending (Reynolds 1942: 150). Baden Powell was approached by some Girl Scouts asking him to do something for them also. In the second edition of Scouting for Boys, he suggested a uniform for Girl Scouts – blue, khaki or grey shirt (as with the boys) and blue skirt and knickers. However, he had decided to set up a separate organization and scheme.

Continue down Henrietta Street. Look for the plaque commemorating Jane Austen above No. 10.

Jane Austen (1775-1817) lived for a time at 10 Henrietta Street. She stayed with her brother in a house on this site between 1814 and 1815. (In fact, it was in her brother’s flat above the bank he owned). She described the building as ‘all dirt and confusion, but in a very interesting way’. Pride and Prejudice was published in 1813, Mansfield Park appeared in 1814 and Emma in 1816.

Turn left down Bedford Street. 50 metres down the road you will come to a junction of Maiden Lane and Chandos Place.

At the turn of the century Bedford Street was the home of many publishing houses were based here – including Heinemann (1889-1911) Macmillan and Co (1864-97) who published Maud Stanley’s work as we will see later; and Edward Arnold (1891-1905). The street was originally built between 1633 and 1640.

Turn right down Chandos Place.

At the end of Chandos Place (at the junction with William IV Street cross over to Adelaide Street.

Then turn quickly right down the pathway by the market in the yard of St Martin in the Fields. Ahead of you is Trafalgar Square, to your right, is the old St Martin’s National School.

Trafalgar Square

The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. In 1699 the newly formed Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge proposed the establishment of a charity school to the parish. (The High School later moved to Tulse Hill SW2). The Society was formed in 1688 ‘to promote religion and learning’ – and had a significant early focus on the education of children through the founding of charity schools such as the High School. However, there was also some early concern with adults. As Kelly (1970: 65) has argued the founding of the Society and the development of this work marked a new phase in religious adult education in Britain. While Puritan ministers had been involved in teaching adults to read (so that they could engage directly with the bible), this was the first time that the Church of England as an institution (albeit through an agency) contributed to the area. SPCK also provided a model of organization that many later charities followed

Schooling. A concrete reminder of educational efforts can be seen to the left of St Martin’s – running the length of the church to Adelaide Street is what was the Vicar’s House, the Vestry Room and the National School. The present building was erected in around 1830.

Youth work and work with homeless people. After the school closed the building was put to various uses including youth work. It also was to house The London Connection – a large agency concerned with the needs of homeless and roofless young people. It provided various services including drop-in provision, washing and other amenities, educational activities, and an advice and bed-finding service. A significant number of detached workers worked well into the night from here, especially in the Leicester Square, Soho and Embankment areas. The church had become well known for its work with homeless people from just after the First World War when Dick Sheppard (the vicar from 1914-1927) established a relief centre in the crypt (Northcott 1937). Sheppard was a popular preacher and pioneer of religious broadcasting. He was also a pacifist and founded the Peace Pledge Union in 1936. The St Martin-in-the-Fields Social Care Unit (which worked with rough sleepers and other vulnerable homeless people) and the London Connection merged in 2003 to form The Connection.

Trafalgar Square and popular education, WC2. The National Gallery (built 1832-8) is to the north of the Square; Admiralty Arch (1910) and The Mall to the west; and St Martin in the Fields to the east. The Square itself was not so named until 1835 and arose out of the redevelopment of the Charing Cross area. The design was by John Nash – famed for his planning of Regent’s Park and Regent Street, the redevelopment of Buckingham House into Buckingham Palace, and the design of Marble Arch and Carlton House Terrace. The Square is on the site of the King’s Mews (Chaucer was once their clerk). By 1500 they were used as stables and later some of the buildings were used as lodgings for Court officials and as barracks for the Parliamentary army during the Civil War (detail from Weinreb and Hibbert 1983).

The Square has long political associations – as a for public meetings and demonstrations. The Chartists began their march here in 1848 (nowadays they tend to end here – such as the famous CND marches of the 1950s and 1960s). As such it has earned itself a place in the annals of popular education. People could come to the Square to hear important (and not so important) political speakers – and to meet other activists.

One of the striking features of galleries and museums in Britain is the extent to which they appear to be concerned with exhibition rather than education. Indeed, compared to North America, there has been relatively little discussion of museums and galleries as sites of popular and informal education. Yet as the 1919 Report on Adult Education put it:

The museum should be at once the workshop of study of the pupil, and a place of regular resort for the general public, attracted there by the variety of its interests and the periodical regrouping of its exhibits. The museum thus conceived, is an educational institution of the highest value and should play an important part in the educational life of the community. (Ministry of Reconstruction 1919: 147)

There is some tradition of museum and gallery education, but it has been largely directed at children. As a result, museum education has not engaged with adult, informal and community education thinking and practice, and a significant resource has lain underdeveloped (see Chadwick and Stannett 1995)

At Trafalgar Square turn right – walk northwards up St Martin’s Place, The National Portrait Gallery (established in 1856, this building opened in 1895) should be on your left. Also on your left is a memorial to Edith Cavell (1865-1915).

St. Martin’s Lane and Five Dials

Walking north we find St. Martin’s Lane. Previous residents of the lane have included Thomas Chippendale at number 60 (the furniture maker) and Sir Joshua Reynolds. Louis Francois Roubiliac, the sculptor had his first studio here in St Peter’s Court (numbers 110-11 on the west side). It was taken over by William Hogarth who founded the St Martin’s Academy in them (1735). This was later to become the Royal Academy. Before the building of Trafalgar Square, it was a narrow street running down to the Strand.

Continue up St Martin’s Lane (The Coliseum Theatre will be on your right).

The area to your right is Covent Garden (bounded by St Martin’s Lane, Drury Lane, Long Acre and a line running roughly parallel with The Strand.

Opposite the Duke Of Yorks Theatre, you will find the Friend’s Meeting House.

Friends Meeting House, adult schools and lifelong learning, St Martin’s Lane WC1. This meeting house opened in 1883, was damaged during the Second World War, and reopened in 1956 (Lee and Lee 1983). The first London meeting house was in Westminster close to the abbey on a site now occupied by Church House and included a school and library (1666 – 1776). The Meeting moved to St Martin’s Lane in 1779 (to a new building close by St Peter’s Court – a site now occupied by or close to the Duke of York’s Theatre).

The influence of Friends on the development of the Adult School Movement – and later the Educational Settlements was significant. In the development of non-conformist Christianity from John Wycliffe and the Lollards, direct access for all to the Bible has been stressed. With it came the need for the ability to read. This was a key concern of the SPCK and of the pioneering work of the Welsh Circulating Schools under the influence of Rev Griffith Jones. They grew with some speed in the first half of the eighteenth century and could be attended by adults as well as young people. Adults could come on weekday evenings or to Sunday Schools.

The first ‘adult school’ is said to have begun in Nottingham in 1798 to meet the needs of young women in lace and hosiery factories. It was independent of any other organization and run by William Singleton (a Methodist) and Samuel Fox (a Quaker) (Rowntree and Binns 1903: 10-11; 26-28). The main focus was on reading the Bible, and then writing from dictation or copies – but there was also a social side to many schools. In London specifically, adult schools appear to have been founded in 1814 in Southwark and 1815 in the City of London (inaugural meeting held at the New London Tavern, Cheapside on July 11). We know this from what is arguably the first study of ‘adult education’ by Thomas Pole (another Quaker) (1816). As the schools developed they developed institutions such as savings funds and coffee carts.

This particular meeting house hosted a range of educational activities. For example, the 1884 annual report listed a Sunday School, Band of Hope, Mutual Improvement Union for Young Women, an Adult School (for men) and a Mother’s Meeting. While the Society may now have a rather middle-class image, at that time ‘tradesmen and handicraftsmen were the chief upholders of Westminster Meeting (Beck and Ball 1869: 249).

Continue walking up St Martin’s Lane. On your left, you will pass Goodwin’s Court and New Row. The White Swan (1 New Row) is mentioned by Charles Dickens in several of his books and Nell Gwyne is said to have been a customer here and supposedly lived close by.

When you come to the junction with Cranbourn Road and Long Acre, look to your left for the site of Slaughters.

Old Slaughter’s Coffee House, 77 and later at 74-75 St Martin’s Lane WC1 . The original Slaughters was established in 1692. It was demolished in 1843 to make way for Cranbourn Street – rather appropriately it would be situated between the Pret A Manger and the Spaghetti House).

Slaughters has several claims to fame. It attracted many artists including Hogarth and Roubiliac; it was a lively house for discussion – Goldsmith wrote in 1765 ‘If a man be passionate he may vent his rage among the old orators at Slaughter’s Chop Shop and damn the nation because it keeps him from starving’ (Weinreb and Hibbert 1983: 561); and it played host to the inaugural meeting of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1824.

Turn right onto Long Acre and right again immediately down Garrick Street, left into Floral Street.

The dark stone building on Garrick Street opposite Floral Street is the Garrick Club (No. 15). The club was established in 1831 by actors. They were being refused membership of the Pall Mall clubs. In 1998 the club was paid £50 million by the Disney Corporation for the rights to Winnie the Pooh which A. A. Milne, a club member, had bequeathed.

The gothic-style building on the corner of Garrick Street and Floral Street was a mission house and school (1860) but soon became a stained glass manufacturer (1864).

Just beyond this building is Rose Street. John Dryden, the poet laureate, was famously attacked here in 1679 by a gang paid by the Earl of Rochester. They (wrongly) believed that Dryden had written an essay satirizing Rochester and the King.

This area was one of the poorest slums in London. It appeared in various guises in the work of Charles Dickens. The area was also an important target for social reformers and workers. Maud Stanley (1833-1915) was an important example of these workers – setting up a refuge, developing Sunday Schools, night classes and a ‘club’. Her work grew out of ‘district visiting’.

Walk a little way up Floral Street, and stop just past Rose Street (it is just a matter of walking a few metres). On your right is Lazenby Court. This is close by one of the main ‘rookeries’ in which Maud Stanley worked.

Stanley, who was the third daughter of the 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley, had been involved in district visiting in St Annes, Soho (the forerunner of the casework element of social work). She lived in Smith Square (No. 32) close to the Houses of Parliament. A co-worker with Octavia Hill (Steman Jones 1984: 204), she argued that more people should be involved in the sort of work and that visiting undertaken by the Charity Organisation Society. In the Five Dials area she was again involved in home visiting – and could bring an ‘exact and critical knowledge of the existing agencies for the relief of poverty and suffering Eager 1953: 66).

A lively account of her work is given in Work About the Five Dials (1878) and it included setting up a refuge, developing Sunday Schools, night classes and a ‘club’. She set out to involve local people as teachers and helpers; and made contact with young men and women on the streets and in the courtyards – as they talked and played cards and gambled.

Now walk through Lazenby Court and under the pub arch (the Lamb and Flag). Ahead of you is Garrick Street. Turn right onto Garrick Street and return to the junction with St Martin’s Lane.

A diversion up Long Acre (if you have time): Walk up Long Acre. On your right, you will find a wonderful 1930s building designed for St Martin’s School of Art (Nos 27-29).

On Long Acre, you will find what was St Martin’s School of Art (27-29 Long Acre, also 16-17 Greek Street and Charing Cross Road WC2). Thought to be one of the oldest art schools in London – originating from one of the mid-eighteenth-century art academies in the district. It was sponsored by St Martin in the Fields in the 1850s but became independent in 1859.

Close by Covent Garden Station – at 48-49 Long Acre we find the building that originally housed the Youth’s Christian Institute. Founded by Quentin Hogg (1845-1903) in 1870 (and developed out of a nearby ragged school). It aimed at providing fellowship, accommodation and an educational programme that included trade classes. The building is currently occupied by Santander.

The Institute was the forerunner to the Regent Street Polytechnic, 309 Regent Street W1. Founded by Hogg in 1892 it was an institution ‘for the promotion of industrial skill, general knowledge, health and well being of young men belonging to the poorer classes’. Kinnaird went on, with T. W. H. Pelham (who was also involved with Hogg and the Institute), to form the Homes for Working Boys in London (1870) (Eagar 1953: 244). Pelham (1847 – 1916) had been called to the Bar and later worked as a senior civil servant. He also wrote the first significant introduction to boys club work (1889) placing a distinctive emphasis on small, local institutions characterised by friendly relationships. Pelham was also the first chair of the London Federation of Working-boys Clubs and Institutes – formed in 1888.

Turn back and walk west past the tube station – and down Long Acre. Then walk along Great Newport Street.

Great Newport Street was built in the early 1600s. In the eighteenth century, it began to be a centre for artists. Joshua Reynolds (1723-92) lived there from 1754 to 1760 (on the site of Nos 10-11 – now the Photographer’s Gallery) having moved from 104 St Martin’s Lane, George Romney (1734-1802) lived there in 1768-9 and Josiah Wedgewood (1730-95) had a showroom on the corner of Upper St Martin’s Lane and Great Newport Street.

The Unicorn Youth Theatre used to be found next to the Photographers Gallery but it has now moved to a major theatre space on Tooley Street close to City Hall. Whilst here they put on children’s theatre for around 8 months of the year, having taken the theatre over in 1967. It was previously the Arts Theatre (a club theatre formed in 1927 and known for putting on new, Avante Garde and often unlicenced plays.

You can also see a plaque to Ken Colyer (1928-88) the English jazz musician at 11-12 Great Newport Street. He played regularly in the basement here – Studio 51 (1950-73).

Soho

Cross St Martin’s Lane, turn left and walk a few metres. Then turn right down Little Newport Street. On your left, just past the Hippodrome, turn down Leicester Court.

The Chinese Community Centre and Community Associations, 2 Leicester Court WC2, formerly at 44 Gerrard Street. There is some debate about what counts as the first community association. The Pettits Farm Association, Dagenham by 1929 had three characteristics linked to community associations: social provision, the development of groups with an educational purpose, and efforts to co-ordinate neighbourhood services (Clarke 1990: 29). However, other possibilities include the Watling Estate Association, Middlesex and the Wilbraham Estate, Manchester. By the late 1930s there were known to be community centres in over 320 towns or new estates (Broady 1979: 5).

As with other community centres, the programme of work that has been based at the Chinese Community Centre was wide – including youth groups, a women’s and elders’ group, and various cultural activities.

The roots of community associations such as this are varied – but the immediate lineage can be traced back through the work of educational settlements such as West Central (featured on the extension to this walk) and residential settlements such as Toynbee Hall, Oxford House and Mansfield House. An emphasis on democracy and participation came strongly through the educational settlements. An interest in social work and social welfare came from the residential settlements. Both settlement movements had a concern with education and the needs of local people. Both made use of clubs and groups as well as more formal educational activities. To these roots must be added the development of village halls. (See Clarke et al 1990).

Walk back up Leicester Court, cross Little Newport Street and walk up Newport Place. Turn left onto Gerrard Street. (This is all a matter of a few metres).

Gerrard Street and Chinatown. Soho is rich in examples of current, recent and older informal education and welfare initiatives. The area around Newport Place was the location of the old Newport Market. By the 1850s it had become a particularly pernicious slum. The old market house was turned into the Newport Market Refuge (Gladstone was one of the committee members). As well as being a refuge there were also training programmes for boys and girls.

Gerrard Street was built in 1677-85 and was initially distinguished by its aristocratic inhabitants. From the mid-eighteenth century, it was better known for its taverns and coffee houses. In the first half of the twentieth century, it became well known for its night clubs, in the 1950s for its striptease clubs and, from the mid-1960s on, as a centre for Chinese cuisine and culture. clubs – see below.

Look to your right, marked by a green plaque – and currently occupied by the Loon Moon Supermarket – you will find: The Literary Club.

The Literary Club. The club was held at the Turks Head Tavern, 9 Gerrard Street, W1. The Club was founded by Joshua Reynolds and Samuel Johnson in 1764 and was probably the most famous of the literary and theatrical clubs in London. Members include Oliver Goldsmith and Edmund Burke. The Club met on Monday evenings at 7.00 – the only matter of conversation excluded being politics. Similar clubs and societies had appeared since the early 1700s – many of those outside London had rather more of an overt educational agenda.

Edmund Burke (1729-97) lived at No. 37 (from 1787-90). He wrote his famous critique of the French Revolution here: Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790). John Dryden (1631-1700) lived in a house at the site of No. 43 between 1687 and 1700 and James Boswell (1740-95) lodged with a tailor at No. 22 in 1775.

The basement of 39 Gerrard Street was the original setting for Ronnie Scott’s jazz club (it opened on October 31, 1959 – and cost 2/6 to get in).

Carry along Gerrard Street. At the junction with Macclesfield Street turn right (north). At the top of Macclesfield Street (a matter of a few yards), you will find Shaftesbury Avenue.

Completed in 1886, Shaftesbury Avenue was part of the redevelopment that flattened the infamous ‘rookeries’. It was named after the social reformer who had so much to do with child protection, ameliorating the conditions of the poor in the area and the development of ragged schooling.

Lord Shaftesbury and the Ragged Schools, Shaftesbury Avenue W1, WC2. Shaftesbury Avenue was named in memory of the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-1885). The Avenue opened in 1886, and while using the route of existing streets, it entailed the demolition, to the east of here, of some of the appalling slums that Shaftesbury sought to eliminate. Whilst known as Lord Ashley, he became involved in factory reform and was responsible for taking three factory acts through Parliament (1847; 1850 and 1859); and the Coal Mines Act (1842) which stopped the employment underground of women and children under 13. He also piloted the Lunacy Act (1845); helped Florence Nightingale with her army welfare and nursing work, and was centrally involved in the YMCA and YWCA. He was concerned with improving housing conditions for poor people.

Shaftesbury was one of the founders of the Ragged Schools Union (which had its headquarters on Shaftesbury Avenue for many years) and was its president for 40 years. The ragged school movement grew out of a recognition that charity, denominational and dames schools were not providing for significant numbers of children in inner-city areas. As the schools developed, many gained better premises and broadened their clientele (age-wise), opened club rooms and hostel and shelter accommodation, and added savings clubs and holiday schemes to their programmes of classes. A good indication of the widening of the work is given by S. E. Hayward’s illustration The Ragged School Tree (an illustration in Montague 1904).

Along the branches, we find coffee and reading rooms, Bands of Hope, Penny Banks, refuges, men’s clubs and sewing and knitting classes. This stood in stark contrast to the narrow focus on the 4 ‘R’s that remained, for example, in the voluntary National Schools. Some of the ragged schools developed into Evening and Youths’ Institutes – such as that established by Hogg, Pelham and others in Long Acre, London in 1870. Other Institutes developed from scratch. Early Institutes like the one established in Dover in 1858, utilized a mix of opportunities for reading, recreation and education.

Reference: Turnbull, R. (2010). Shaftesbury. The Great Reformer. London: Lion.

Crossing Shaftesbury Avenue we find Dean Street and at number 57 the old home of St. Anne’s – and the origins of some important youth work initiatives of the 1960s – Centrepoint, New Horizons and The Rink.

St Anne’s has long been a centre for social action in Soho (certainly since the 1880s). The church was severely damaged in the Blitz but was rebuilt in 1991 and includes flats, a community centre and offices. These buildings and the church tower lie behind No. 57.

Kenneth Leech (1939-2015) and St Anne’s, 57 Dean Street. Leech was, for some years (1967-1974), the curate at St Anne’s, Soho. Whilst there he initiated, and was involved in, several key projects around working with young people. At that time, as now, the area attracted a large number of young people. Many lived in and around London and were drawn to the various clubs and networks that could be found in the area. Perhaps the two most significant issues were drug usage and crime. However, there was also a growing number of young people drawn to London by the prospect of employment from Scotland and Northern England – and who were unable to find places to live. Kenneth Leech believed that a significant aspect of his ministry should be devoted to the needs of these young people. The house became the centre for several influential detached and project work initiatives in the second half of the 1960s and early 1970s. Leech lived in the flat above – along with several young youth workers. The following initiatives developed from, or were associated with them:

- Centrepoint-Soho began in December 1969 and was initially aimed at young ‘drifters’ newly arrived in London. It comprised emergency accommodation, food, advice and referral to other agencies. The charity took its name from Richard Seifert’s office tower on Tottenham Court Road – Centre Point – which had remained empty for a long time to exploit a legal loophole, and in the process make a considerable amount of money for the developer. The first emergency accommodation was in the basement of St Anne’s House. The project took off – and other centres were opened

- New Horizons (now on Chalton Street) a project for young homeless people also began on the ground floor here as an open-door advice centre.

- The Rink (a Salvation Army project) was developed by the young workers who lived at St Annes, and was an experimental all-night club on Oxford Street (273) which provided music and food. They were also involved in The Crypt (St Martin in the Fields) – a day shelter offering basic sleeping facilities; and in street and detached work in and around the coffee bars, clubs and other meeting places in the area. The Rink was a Salvation Army youth project. It then merged with another local youth work initiative – the Soho Project (started in 1957) – which, in turn, was to become part of the London Connection.

Kenneth Leech has also been a significant contributor to the literature of both work with young people and those with problems around drug usage, Christian Socialism, and debates around the role of the church and Christians in contemporary society. His books include Youthquake (1973), The Social God (1981), and Soul Friend (1994). In 1974, after he left St Anne’s to become Rector of St Matthew’s Church, Bethnal Green, he helped to found the influential Jubilee Group ‘a loose network of socialist Christians who stand mainly within the Catholic Tradition of Anglicanism’ (see Leech 2001).

Walk on up Dean Street. Go past Romilly Street and Compton Street. On your right you will see the Quo Vadis Restaurant (number 28) founded in 1926.

The rooms at 28 Dean Street were rented by Marx at £22 a year. He described it as a ‘hovel’. A Prussian agent who visited them there reported that they lived:

in one of the worst, and hence the cheapest quarters of London. He has two rooms, the one with the view of the street being the drawing-room, behind it the bedroom. There is not one piece of good, solid furniture in the entire flat. Everything is broken, tattered and torn, finger-thick dust everywhere, and everything in the greatest disorder; a large, old fashioned table, covered with waxcloth, stands in the middle of the drawing-room, on it lie manuscripts, books, newspapers, then the children’s toys, bits and pieces of the woman’s sewing things, next to it a few teacups with broken rims, dirty spoons, knives, forks, candlesticks, inkpot, glasses, dutch clay pipes, tobacco-ash, in a word all kinds of trash, and everything on one table; a junk-dealer would be ashamed of it. When you enter the Marx flat your sight is dimmed by tobacco and coal smoke so that you grope around at first as if you were in a cave, until your eyes get used to these fumes and, as in a fog, you gradually notice a few objects. Everything is dirty, everything covered with dust; it is dangerous to sit down. Here is a chair with only three legs, there the children play kitchen on another chair that happens to be whole; true — it is offered to the visitor, but the children’s kitchen is not removed; if you sit on it you risk a pair of trousers. But nothing of this embarrasses Marx or his wife in the least; you are received in the friendliest manner, are cordially offered a pipe, tobacco, and whatever else there is; a spirited conversation makes up for the domestic defects and in the end you become reconciled because of the company, find it interesting, even original. This is the faithful portrait of the family life of the communist leader Marx. (quoted by Summers 1991: 120 – 121)

While living in Dean Street, Marx gave lectures in a room above the Red Lion pub on Great Windmill Street. However, his time in London will be best remembered for his association with the British Library Reading Room. There he began the research that led to his great works of political and economic analysis: Grundrisse der Kritik der politischen Ökonomie (1857-58) Zur Kritik der politischen Ökonomie (1859) and Das Kapital (Volume 1 1867 – two further volumes were added in 1884 and 1894). Later in 1855, Jenny received two small inheritances – and they were able to move to a small terraced house near Primrose Hill. For an assessment of Marx’s contribution to education see Barry Burke’s piece: Karl Marx and education.

Turn back down Dean Street and left into Bateman Street. On your right, you will pass the Chinese Workers Association and then you will find Frith Street.

Turn left (north) up Frith Street. Immediately on your right at number 8, you will find the former home of Lily Montagu’s West Central Club.

Lily Montagu and club work, 8 Frith Street (1873-1963), with Maud Stanley, is one of the key figures in the development of girls’ clubs and work with young women. Her contribution was fourfold. First, she was a committed worker with young people. As a young woman (19) in 1893 she set up the club with her cousin in two rooms at 71 Dean Street W1 (the club was later to move to 8 Frith Street, then 8 Dean Street). The character of her work can be gauged from her comments: ‘A club worker must enter on her career in the learning spirit. She must not attempt to foist her standards on the girls among whom she intends to work. She must study their standards, and exchange her point of view with theirs’ (Montagu 1954: 24). She emphasized sharing the government of the club with members; and on educational endeavours. The latter included discussions around various moral questions, citizenship, and citizenship. There was also a flourishing drama group. Second, Montagu placed a particular emphasis on campaigning and working for the improvement of young women’s working conditions – and this she carried into the political arena via organisations such as the Women’s Industrial Council. Third, she was central to the formation and development of the National Organization of Girls Club (later to become Youth Clubs UK). Last, she has left several important additions to the literature of youth work – including the account of her work at West Central (Montagu 1904; 1954).

In 1919 Lily Montagu and her sister set up the West Central Club and Settlement in Alfred Place (the site is now occupied by a rather undistinguished office building – Remax House used by University College Department of Economics). Tragically, on the night of April 16, 1941, the building was hit in an air raid and completely demolished. 27 lives were claimed. The club then occupied 5 different premises for ten years before moving into premises in Hand Court, Holborn WC1. For a full biography see Lily Montagu by Jean Spence.

Look to your left and you will see the former home of William Hazlitt (number 6).

Having looked at numbers 6 and 8 walk south (over Bateman Street). Further down Firth Street (on your left opposite Ronnie Scott’s), you can see where Mozart lived (number 20), and where John Logie Baird gave the first demonstration of television (number 22). The building now has the Bar Italia on the ground floor.

John Logie Baird (1888 – 1946) – television and self-education, 22 Frith Street. Baird was an electrical engineer who when forced by ill-health into early retirement, pursued a long-held interest in transmitting pictures. In the summer of 1924, he rented a two-room attic at 22 Frith Street and set it up as a laboratory. For the next 18 months, he conducted a series of experiments that led to his demonstrating his “noctovision” to members of the Royal Institution at his laboratory on January 27th, 1926 – the first public demonstration of the medium. Several people were working on picture transmission at the time. Baird’s system used infrared rays to communicate pictures from a darkened room. From there he went on to transmit pictures between London and Glasgow using telephone lines in 1927. A year later he used radio waves to transmit pictures between London and New York. His company, Baird Television Development Company, made the first programme for the BBC (broadcast on September 30, 1929). His mechanical system was only to have a short lifespan – it was replaced by an electronic system developed by Marconi and EMI.

Not surprisingly, television has become the central means by which many people educate themselves. Through news and current affairs coverage, educational programming, documentaries and drama it has allowed us to expand our knowledge of the world and other cultures. It is a powerful socializing force and, as a result, is a central focus for politicians, business people and others who want to influence large numbers of people. It is hardly surprising that in most countries television channels have either become arms of the state or fiercely guarded as commercial properties – cash cows fed by advertising. In Britain, the main terrestrial channels have had to operate within a legislative framework that has sought a strong public service orientation. Their task has been not only to entertain but also to inform and to educate.

Return to Bateman Street and carry on down to Greek Street. Ahead of you on Greek Street is the facade of the St James and Soho Working Men’s Club.

Greek Street and Soho Square

Running parallel with Dean Street is Greek Street. Greek Street has always had a colourful air. Indeed, a police inspector reported to Royal Commission in 1906 that it was ‘the worst street in the West End’. Casanova stayed here in 1764, Thomas De Quincey (writer of Confessions of an Opium Eater) lived here in the early 1800s. Josiah Wedgewood had his London showrooms at numbers 12-13 from 1774-1797 (marked by a plaque). Next door (and opposite the end of Bateman Street) you will see a wonderful facade from the St James and Soho Working Men’s Club – erected when it moved here from Gerrard Street. The Club was an early and important example of the movement in London.

Solly argues that the Colonnade Working Men’s Club, Clare Market, WC2. was the first institute to use ‘club’ in its title (Solly 1867). It opened in 1852 to provide wholesome and constructive amusement, newspapers, books and later refreshment (strictly temperance). The club format was seen by its supporters as the right milieu for more subtle forms of education. It offered recreation (Solly thought this to be a basic need of social welfare) but it also provided ‘an informal teaching situation into which more serious matters could be gradually introduced’ (Baily 1987: 120). Everyday talk could lead to regular classes (here political economy was stressed) – but that should not be the only fare.

Many of the early attempts such as the Colonnade were not very successful. In 1859 its premises were opened as the Colonnade Boys’ Home and Club. It included lodgings for 18 boys and eighteen young women; bible classes and night schools for both sexes, educational classes; a soup kitchen; and a laundry (Eagar 1953: 155). The site is now occupied by the London School of Economics. Initially, these institutes and clubs were temperance – which was a source of some contention. They were a middle-class initiative aimed at working-class men – however, with the promotional power of Solly and the Union, a significant number of clubs were established (55 alone in its the CIU’s second year). The London clubs, in particular, began to attack patronage, there was a strong campaign for the sale of beer. Through these efforts in the 1870s middle class influence waned (see Tremlett 1987).

There were several working men’s clubs in this district (Soho and St. Giles). This particular club was said to have 550 members in 1883. For various reasons, the clubs were a base for radical political activity. They were mutual aid institutions that gave great opportunities for debate. Especially important here were the Sunday evening meetings where various political and practical questions were debated (Shipley 1987). But they also provide a site for recruitment and organization such as was the case with the Manhood Suffrage League in the early 1880s. See Henry Solly and the Working Men’s Club and Institute Union.

Turn left up Greek Street. On your left you will find The Soho Club and Home, 59 Greek Street W1. Check the plaque by the side of the door.

The Soho Club and Home, 59 Greek Street W1. Maud Stanley founded the Soho Club for Girls in 1880. It had originally begun in three rooms in Porter Street, Newport Market. A refuge had been set up there in some old market buildings that also provided training and meals for boys.

59 Greek Street was built in 1883 as the Soho Club and Home for Working Girls. In the 1920s it became the Theatre Girls Club, a home for women working in the theatre and later a hostel for homeless women.

In some respects, the Club and Home resembled the earlier efforts by workers at the Colonnade Home and Club (see above). However, the nature of much girls club work at that time tended to emphasize relationships and gentle improvement so that girls may ‘ennoble the class to which they belong’ (Stanley 1890: 48). This could be contrasted with the talk of character-building and muscular Christianity that could be found around some boys work. It was open every evening of the week. Its programme included classes in drawing, French, singing, needlework, music, gymnastics and mathematics. The club had a library, canteen and a low-cost medical dispensary for its members. The short and long-term lodgings it provided for ‘Young Women engaged in business, and students’ could be had for between 3s and 7s 6d per week (depending on whether they slept in a dormitory or had a private room). This price included the use of a sitting room, gas fire and clean bed linen (see Summers 1989: 123-4).

Stanley’s significance for youth work is great. She wrote the first substantial text on clubs for girls (1890); and took some efforts to facilitate inter-club links – establishing the Girls Club Union in 1880. It later became known as the London Girls’ Club Union and, along with the Federation of Girls Clubs (run under the auspices of the YWCA) and the Social Institutes Union, was reconstituted in the late 1930s as the London Union of Girls (now Youth) Clubs.

You now walk back a couple of steps and turn up Manette Street (almost opposite the Soho Club and hostel). Under the archway, on the wall of ‘The Pillars of Hercules’ you will see a notice outlining the history of the pub and the street. On your left, you will see the chapel of St Barnabas in Soho. on your right is Foyles Bookshop.

Look through the arch opposite and you will find Manette Street. On our left is the chapel associated with The House of St Barnabas (see below). On our right is Foyles Bookshop – one of many along Charing Cross Road – and a reminder of the expansion of book ownership at the turn of the century.

The House of Charity (The House of St Barnabas-in-Soho), 1 Greek Street WC1. The shell of the house was built in 1746 as part of a speculative development and stood empty for eight years until Richard Beckford took it over (his brother William Beckford, the Lord Mayor of London lived a few doors away at 22 Soho Square). In under three months the house was completed and boasts what is said to be one of the finest English rococo-style interiors in London. Of particular interest is the drawing room of the house (known now as the Council Room). This is on the first-floor corner of the house and overlooks Greek Street and Soho Square. It has a very elaborate ceiling – and a very fine fireplace (sold in 1864 to help pay for the chapel on Manette Street).

Soho became a far less fashionable place – and the house proved hard to sell. In 1811 it became the offices of the Westminster Commissioner for Works for Sewers (later known as the Metropolitan Board of Works – the first metropolitan-wide local government for London – established in 1855). Under Sir Joseph Bazalgette (the chief engineer) the Commissioners not only set about one of the most significant engineering feats of the nineteenth century – the construction of the sewage system and the bringing of piped water to houses to replace the infamous system of street water pumps – it was also to oversee the development of Charing Cross Road, Shaftesbury Avenue and other major streets.

In 1862 the house was taken over by The House of Charity. It had been established in 1846 to provide temporary accommodation for homeless poor people. A distinguished group of Anglicans were responsible for setting up and running the house. These included: Dr Henry Munro (of Bethlehem Hospital – ‘Bedlam’) W. E. Gladstone (then Colonial Secretary and later Prime Minister) and F. D. Maurice (Professor of Theology at Kings College and later known as a key Christian Socialist and founder of the Working Men’s College). Their first property was round the corner at 9 Manette Street (then Rose Street). It was a former workhouse designed by James Paine Jnr. in 1770. The House of Charity was one of the first hostels in London – and helped over 300,000 people. The concern was to provide short-term accommodation while people got on their feet. Daily church attendance was expected – hence the fine little chapel (on Manette Street). There were plans to build a substantial community here – but these had to be left on one side as money got short. Charles Dickens used the house and gardens as a model for the London lodgings of Dr Manette and Lucy in Tale of Two Cities. There has been some debate about when and how he came to know the house. It might be that he visited the house while the Board of Works occupied it. Another version has him staying there for a while after he broke up with his wife – and that he wrote some of Tale of Two Cities while there.

In March 2006 the House stopped providing residential accommodation. The Charity continues to provide a range of training and educational opportunities for those who have experienced homelessness.

Foyles Bookshop and the diffusion of knowledge, 119-125 Charing Cross Road, WC2. Opened here in 1906 by two brothers William and Gilbert Foyle (but traded elsewhere beforehand). It was said to be the biggest bookshop in London – but for many years was a source of severe irritation to many customers owing to its organization! Charing Cross Road has long been known for its booksellers and immortalized in the book by Helen Hanff 84 Charing Cross Road – based on her correspondence with Marks and Co (now demolished).

Independent and direct access to books has been of fundamental importance to the diffusion of knowledge and the development of thinking. With Willam Caxton’s introduction of the printing press to England in 1476 cheaper books became possible. (He set up his first press in a shop in the precincts of Westminster Abbey). As the technology developed, and costs reduced, evangelists such as John Wesley and Hannah More, and radicals such as William Lovett sought to promote the use of books. We see the emergence of those like Charles Knight (1791-1873) and his Society for the Diffusion of Popular Knowledge who developed new, popular, reading materials. However, it was with the introduction of mass production that bookshops such as Foyles came into being. Of particular significance was the development of popular series based on cheap reprints: Nelson’s New Century Library (1900), World Classics (1901), Collins Pocket Classics (1903) and Dent’s Everyman’s Library (1906) (Steinberg 1961: 348-361). Such series included classic novels, works of antiquity and key philosophers and political thinkers. They allowed people to own, rather than borrow, texts. In the 1930s we see the introduction of 6d paperbacks (Penguins and Pelicans) which further enhanced access.

Turn back and walk up the rest of Greek Street. We walk past Milroys at No 3 – the best shop for whiskey in London (and the only remaining example of a Georgian shop front in Soho)’ At the top of the street on the right (east side), we find the main entrance to The House of St Barnabas. On entering Soho Square cross and walk through the gardens in the centre of the square.

Soho Square. Soho Square was originally designed by Gregory King and laid out in the 1680s. Richard Frith – a speculative builder (who soon went bust) put up the first houses. It was designed to be a grand place to attract nobility. However, most had left for Mayfair and Picadilly by the 1770s. The gardens at its centre were set out around a statue of Charles II by Caius Gabriel Cibber. The statue is still there – but much diminished. The large stone fountain which it topped was removed in the 1870s. The small half-timbered building at its centre was built in 1876 and is a garden shed. The Square was the haunt of publishers (A. C. Black at No. 2 – now occupied by Bloomsbury Books; George Routledge at No. 36) and is now the home of the British Board of Film Classification (No. 3). No. 8 became a school, and Crosse and Blackwell’s the sauce makers occupied No. 21 (and later Nos. 20 and 18). They had a factory and warehouse to the rear. On the eastern side of the square, Mrs Theresa Cornelys (who had a daughter by Casanova) ran a well-known club at Carlisle House in the 1760s and 1770s (the site is now occupied by St Patrick’s Church – built in 1893).

To the north of the square close to Soho Street, you will find a blue plaque honouring Mary Seacole.

Mary Seacole (1805-1891) and nursing, 14 Soho Square W1. Mary Seacole’s work nursing and caring for injured soldiers during the Crimean War was, at the time, almost as well known as that of Florence Nightingale. She had applied to join Nightingale’s team but had been rejected (even though she was highly experienced in dealing with cholera. Having been successful in business in Jamaica, Seacole funded her passage, set up the British Hotel close to the battlefront and used the money she made to treat soldiers from both sides on the battlefield (Nightingale’s hospital was some miles from the front).

Leave Soho Square and walk up Soho Street. On your left is Gorvinda’s – an excellent value Hare Krishna cafe.

Cross over Oxford Street and go up Hanway Street (slightly to your right). Hanway Street is a shabby, but engaging street with a mix of specialist shops. Our interest here is that one of the shops housed William Godwin’s juvenile library/children’s bookshop.

Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road

William Godwin, alternative education and the juvenile library, Hanway Street, 191 The Strand and 27 The Polygon. William Godwin (1756 – 1836) was the first person ‘to give a clear statement of anarchist principles’ (Marshall 1993: 191). He was

He gained a great deal of fame (and some notoriety) at the time of the French Revolution through his philosophical work (most notably An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice 1793) and his novels (especially The Adventures of Caleb Williams 1794). His educational thinking was distinguished by:

- A respect for the child’s autonomy which precluded any form of coercion.

- A pedagogy that respected this and sought to build on the child’s own motivation and initiatives.

- A concern about the child’s capacity to resist an ideology transmitted through the school.

He gradually became a rather forgotten figure – although he continued to write. After Mary Wollstonecraft’s death Godwin married again – Mary Jane Clairmont, a neighbour. Together they set up a Juvenile Library in Hanway Street in 1805. They produced a series of pioneering children’s books – some by Godwin, many by other writers and published from the shop in Hanway Street. Later they were to move the business to Holborn – but they were continually beset by financial problems – and the debts rose. He died in 1836 and was buried, at his request, next to Mary Wollstonecraft.

Continue up Hanway Street. As you come in sight of Tottenham Court Road you will see a turning on your left – Hanway Place. Walk a few metres up the turning and before you is the old Westminster Jew’s Free School.

Return to Hanway Street, turn left and continue to Tottenham Court Road.

Across Tottenham Court Road we find the concrete towers of what was built as the Central YMCA (on the site of an older YMCA built in 1911-12). One of the founders of the YMCA, George Williams (1821-1905) lived close by on Russell Square (the site of the house is now marked with a blue plaque).

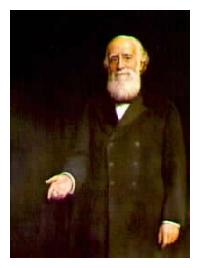

Cross Tottenham Court Road and take a few steps up Great Russell Street. On your left, you will find the doors of the Central YMCA. Just step in and admire the portrait of George Williams.

The original, Central, YMCA on the corner of Great Russell Street was built in 1911-12 (architect R Plumbe). It had all the distinctive features of a large urban YMCA – halls for meetings, restaurants, a gymnasium, swimming baths, social rooms, a boys’ department and 240 bedrooms. It provided a wide range of recreational and educational activities. The new building opened in 1976 (designed by the Ellesworth Sykes Partnership), had a similar range of facilities, although greatly extended, and became particularly well known for its various fitness programmes. It closed in February 2025. Rising costs, demographic changes, shifts in social habits and other factors led to the closure of the Central YMCA after 180 years of work.

From 1857 George Williams (1821-1905) lived close by – first at 30 Woburn Square, then at 13 Russell Square WC1. The Russell Square House was given by the Williams family to be the headquarters of the National Council of YMCAs for England, Ireland and Wales. Neither of these properties remains, although since 1994, there has been a blue plaque on the north side of Russell Square commemorating Williams.

You can either continue up Great Russell Street for the extension to the walk (in preparation) – or return to Tottenham Court Road and turn left (south). The underground station is just a few metres away on the corner with Oxford Street

References

Ackroyd, P. (1994). Dickens, London: Mandarin.

Avery, D. (1995, 1999). The House of St Barnabas-in-Soho. London: The House of St Barnabas-in-Soho.

Baden-Powell, R. S. S. (1899). Aids to Scouting for N. C. O.s and Men. Aldershot: Gale and Polden.

Baden-Powell, R. S. S. (1908). Scouting for Boys (in six parts). London: Horace Cox. (A complete set of the six parts was republished in 1935 by the Scout Book Club). The first book edition details are as follows: R. S. S. Baden-Powell (1908) Scouting for Boys. A Handbook for instruction in good citizenship. London: Horace Cox. A substantially revised edition was published by Pearson in 1909.