Mark K Smith explores how, in the context of the ‘new normal’, educators, pedagogues and practitioners need to offer hope to children and young people. This article is part of a series: dealing with the new normal • offering sanctuary • offering community • offering hope]

contents: introduction • what is hope? • being hopeful • building hope • four key concerns • conclusion • further reading and references • how to cite this piece

I think that of all the attributes that I would like to see in my children or in my pupils, the attribute of hope would come high, even top, of the list. To lose hope is to lose the capacity to want or desire anything; to lose, in fact, the wish to live. Hope is akin to energy, to curiosity, to the belief that things are worth doing. An education which leaves a child without hope is an education that has failed. (Mary Warnock 1986: 182)

Sanctuary allows people space, community a sense of belonging and networks to use and contribute to. And hope…?

The meaning of hope is something that philosophers have argued over for centuries and our understanding of it is ever-changing. Some, even seem to argue within themselves.

What is hope?

Hope is something more than optimism. It is not simply looking on the bright side or believing that ‘everything was, is, or will be fine’ (Solnit 2016: 12). For a start, hope can be for things that we judge to be unachievable. Furthermore, ‘looking on the bright side’ can work against working to make things better. It both warps our view of reality and reduces the motivation to act. There is no need to change if things will change anyway.

John Macquarrie (1978) has given us a starting point for thinking about what hope might be. For him hope was:

An emotion. Hope, he says, ‘consists in an outgoing and trusting mood toward the environment’ (op. cit.: 11). We do not know what will happen but take a gamble. ‘It’s to bet on the future, on your desires, on the possibility that an open heart and uncertainty is better than gloom and safety. To hope is dangerous, and yet it is the opposite of fear, for to live is to risk’ (Solnit 2016: 21).

A choice or intention to act. Hope ‘promotes affirmative courses of action’ (Macquarrie 1978: 11). Hope alone will not transform the world. Action ‘undertaken in that kind of naïveté’, wrote Paulo Freire (1994: 8), ‘is an excellent route to hopelessness, pessimism, and fatalism’. Hope and action are linked. Rebecca Solnit (2016: 22) put it this way, ‘Hope calls for action; action is impossible without hope… To hope is to give yourself to the future, and that commitment to the future makes the present inhabitable’.

An intellectual activity. Hope is not just feeling or striving, according to McQuarrie it has a cognitive or intellectual aspect. ‘[I]t carries in itself a definite way of understanding both ourselves – and the environing processes within which human life has its setting’ (op. cit.).

This provides us with a starting point and language to help make sense of things; a ‘vocabulary of hope’ to imagine change for the better. However, it does leave some questions.

On reason and life after death

John MacQuarrie was concerned with Christian hope. This is hope which goes, in the end, beyond evidence – and looks to the possibility of a life after death. It is wrapped up with, but different from, faith and love (see Augustine of Hippo circa 420 and Aquinas circa 1270). This orientation worried many philosophers. First, there were those who did not like the disconnect from reason; second, those who questioned the existence of God and an afterlife.

The disconnect from reason: ‘For what may I hope?’ was, for Immanuel Kant (1787), up there with ‘What can I know’ and ‘What should I do?’ as one of the central questions of philosophy. The task was to be clear on the connection between hope and reason. In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant focuses on hope as an attitude ‘that allows human reason to relate to those questions which cannot be answered by experience’ (Bloeser and Stahl 2017). It is fundamentally concerned with happiness and there were three primary objects of hope:

- one’s own happiness (as part of the highest good);

- one’s own moral progress; and

- the moral improvement of the human race as a whole (op. cit.).

His argument was that while we may lack evidence for life after death, reason makes it necessary to assume it is possible (Kant 1788). Others were less tolerant of this position.

God and life after death. ‘Stay true to the earth and do not believe those who talk of over-earthly hopes’ wrote Friedrich Nietzsche (1883/5|2005: 7). He disputed Kant’s approach and conclusions and called hope ‘the worst of all evils because it prolongs the torments of man’ (Nietzsche 1878|1994 ). However, after earlier doubts, he did look to hope as a strong earthly emotion. This view of hope was grounded in trust in people’s capacity to bring about desired outcomes (Bloeser and Stahl 2017) rather than in an afterlife. ‘For that humanity might be redeemed from revenge: that is for me the bridge to the highest hope and a rainbow after lasting storms’ (Nietzsche (1883/5|2005: 82).

Looking to learning

John Dewey (1919) similarly placed hope in the human capacity to learn from life – and believed there is enough goodness in life to allow us to make things better. This contrasts with Macquarrie’s approach in several respects.

First, Dewey did not look to what is immutable or ultimate (whether it be God, nature, reason or ends). That said, he did turn to nature in the sense that he believed that the impulse to hope is innate. ‘Humans have a native sense that their activities will yield positive rather than negative results’ (Fishman and McCarthy 2007: 15).

Second, John Dewey’s focus on learning from life and experience does not start with an end or aim.

It is not propositions, not new dogmas and the logical exposition of the world that are our first need, but to watch and continually cherish the intellectual and moral sensibilities and woo them to stay and make their homes with us. Whilst they abide with us, we shall not think amiss. (Waldo Emerson quoted by Dewey 1903)

Rather, hope is to take a path, cultivate understanding and to see where it leads us. Learning of this kind is informed by an attitude or haltung (see below). In Dewey’s case this was an orientation to the well-being of all and to the process of learning from, and engaging with, experience.

Third, Dewey’s view of learning (and living) involved cooperation and conversation. He saw dialogue as being, at heart, a hopeful activity. It involved listening to oneself and others, exploring, and coming to some sort of shared understanding. For Richard Rorty (1999: 145), what was being offered was hope rather than truth. Some years later, Jürgen Habermas’ (1984, 1987) theory of communicative action shared a similar logic. [We explore the nature of conversation and dialogue on another page].

For Dewey, as for Habermas, what takes the place of the urge to represent reality accurately is the urge to come to free agreement with our fellow human beings – to be full participating members of a free community of inquiry. Dewey offered neither the conservative’s philosophical justification of democracy by reference to eternal values nor the radical’s justification by reference to decreasing alienation. He did not try to justify democracy at all. He saw democracy not as founded upon the nature of man or reason or reality but as a promising experiment engaged in by a particular herd of a particular species of animal – our species and our herd. He asks us to put our faith in ourselves – in the utopian hope characteristic of a democratic community – rather than asking for reassurance or backup from outside. (Rorty 1999: 142)

The ecology of hope

Dewey’s concern with nature and interaction links to modern-day explorations of systems and ecology. As humans, we can be seen as part of what Fritjof Capra (1996) has described as the web of life – and it is out of interactions within that web that hope arises. It is not something that happens ‘within’ an individual (see self, selfhood and understanding).

This perspective involves viewing the world around us as an integrated whole rather than a collection of separate parts. Often when people talk about ‘nature’ they are referring to a world where humans are left out, separate from nature. Rather than discussing our impact on nature, we can look at our role in nature. Sometimes called ‘deep ecology’, this orientation looks to ‘the intrinsic value of all living beings and views humans as just one particular strand in the web of life’ (Capra 1996: 6). Such awareness can also flow into the spiritual or religious for those who see God in nature.

With, for example, the development of bio-ecological theory, we can also see how different environments influence child development (and how children impact on those environments) (Brofenbrenner 1979). In the process, we may also gain a better understanding of hope. Sophie C. Yohani has highlighted three aspects that link to the discussions by John Dewey and Richard Rorty. These are that hope is:

- contextualized, often embedded in our personal experiences. As Marcel (1962) has argued, hope allows people to find meaning, begin to see a future and cope with losses and other life challenges.

- a relational process. It develops in relationships where there are trust and care.

- a dynamic, active process (Yohani 2008: 312)

So, what is hope?

In answer to our question, ‘What is hope?’, we can say it is a process of us:

- learning from our experiences and conversations,

- thinking about what we would like to happen and steps we might need to take, and

- believing in the possibility of it happening.

These three elements connect with what John MacQuarrie was proposing but are not dependent on there being ‘ultimate ends’ and look to learning and cooperation – with each other and the world of which we are a part. There is an ‘us’ in hope as well as an ‘I’.

Being hopeful

Within psychology, there has been significant work around what might make people hopeful and how that might impact on physical and mental health and the way in which we function (Gallagher and Lopez 2018). We have already noted the contribution of bio-ecological theory (Brofenbrenner 1979) and developmental psychology, and to this, we can add work within positive, educational, and counselling psychology. Sophie Leontopoulou (2020) sums its significance up as follows:

Hope lies at the core of the human psyche. It has a unique power to propel individuals, groups, organizations, and communities to action and can sustain their energies on the road to achieve everything they value. Interventions and programs developed with a view to instil and maintain hope can significantly aid the promotion of mental and physical health, the enhancement of well-being and positive development and adaptation, and the reduction of psychopathology.

One of the most interesting contributors has been Rick Snyder, a professor whose own battle against chronic pain was part of the reason he researched hope. He has focussed on the psychology of creating pathways. Snyder and his colleagues argued that hopeful thought ‘reflects the belief that one can find pathways to desired goals and become motivated to use those pathways’ (2002: 257-76). He also stressed the importance of agency – the belief that we have the capacity to act to change things. Snyder also proposed that such hope serves to drive the emotions and well-being of people.

Rick Snyder focused on cognitive processes, others – especially those linked to ‘positive psychology’ – have looked to hope as a character strength (see Peterson and Seligman 2003; Seligman 2003). While there is a great of interest in this work – and evidence it can be helpful (see the review by Sophie Leontopoulou 2020) – they are largely set within a ‘treatment framework’ and are based in ‘interventions’. This is a rather different orientation to our focus here. In what follows I have drawn upon Snyder’s approach – but placed it within ways of thinking about hope that looks to being hopeful rather than just hopeful thinking (important as it is). Not surprisingly, given our focus here, it looks to the question ‘how am I to best live my life?’.

It is also important to bear in mind that pedagogues, workers and educators, act in hope. Underpinning our actions is an attitude or virtue – hopefulness (Halpin 2003b). As bell hooks (2003: xiv) put it, ‘we believe that learning is possible, that nothing can keep an open mind from seeking after knowledge and finding a way to know’. In other words, we invite people to learn and act in the belief that change for the good is possible. This openness to possibility is not blind or over-optimistic. It looks to evidence and experience and is born of an appreciation of the world’s limitations (Halpin 2003a: 19-20).

an orkney greenhouse | infed

Building hope

The approach we are discussing here is not goal-oriented in the way that many self-help books and state curricula are. You set a goal, then plan how to achieve it, and test to see whether it has been achieved. Instead, it flows from what we discussed earlier. As pedagogues, workers and educators we invite people to reflect, commit and act. It is a process that we can do for ourselves and encourage others to develop.

Alison Gopnik (2016) has provided a helpful way of understanding this orientation. It is that educators, pedagogues and practitioners need to be gardeners rather than carpenters. A key theme emerging from her research over the last 30 years, is that children learn by actively engaging their social and physical environments – not by passively absorbing information. They learn from other people, not because they are being taught – but because people are doing and talking about interesting things. The emphasis in a lot of the literature about parenting (and teaching) presents the roles much like that of a carpenter.

You should pay some attention to the kind of material you are working with, and it may have some influence on what you try to do. But essentially your job is to shape that material into a final product that will fit the scheme you had in mind to begin with.

Instead, Gopnik argues, the evidence points to being a gardener.

When we garden, on the other hand, we create a protected and nurturing space for plants to flourish. It takes hard labor and the sweat of our brows, with a lot of exhausted digging and wallowing in manure. And as any gardener knows, our specific plans are always thwarted. The poppy comes up neon orange instead of pale pink, the rose that was supposed to climb the fence stubbornly remains a foot from the ground, black spot and rust and aphids can never be defeated.

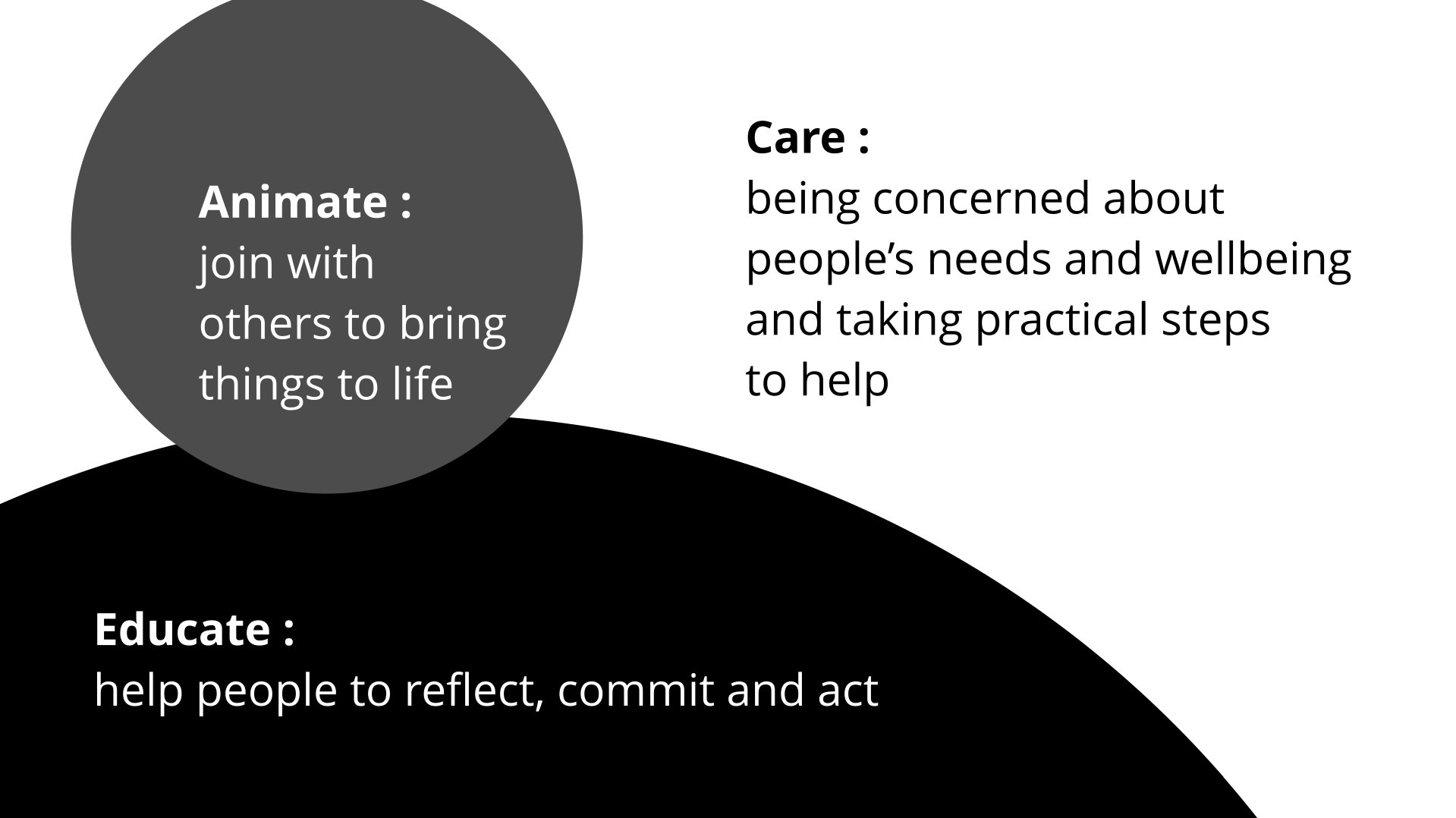

The image of gardening connects nicely with that of pedagogy, which can be viewed as a process of accompanying people, and:

- bringing flourishing and relationship to life (animation)

- caring for, and about, people (caring); and

- drawing out learning (education) (Smith 2012; 2019a).

We find this focus right from the start in the distinction made within ancient Greek society between the activities of pedagogues (paidagögus) and subject teachers (didáskalos). The latter, as Kant (1900: 23-4) put it, ‘train for school only, the other for life’. In short, pedagogues set out with the idea that all should share in life, and an appreciation of what people may need to flourish. In many ways we are also asking the same questions as Kant (1787) – What can I know? What ought I to do? What may I hope?

Four key concerns

From our discussion, we can see that we need to be doing at least four things.

Picking up on questions or situations with a concern for flourishing. We encourage people to look to questions or situations that an individual or group want exploring. We foster reflection: going back to experiences, attending to, and connecting with feelings, developing understandings.

We also need to think about how we approach this reflection and – indeed – the rest of our journey. We need to think about our disposition – or what German social pedagogues call Haltung. It is sometimes translated as mindset or attitude, but it is more about how actions are influenced and guided by what we believe in. Here we are going to turn back to Aristotle and the ancient Greeks and use what they called phronesis. This is a moral disposition to act truly and rightly, a concern for flourishing.

Thinking about what might be good. We all come to situations and questions with some idea of what might make us or others happy in life. Over time we reflect on our experiences, and the situations that others have faced, and gain some insights. Sometimes, perhaps because of the way we are feeling or because we want to avoid looking at some aspect of our or other’s behaviour, we get things wrong or appreciate only half a situation. As pedagogues, workers and educators we can listen and learn from the experiences of others. We can also look at research on what people say makes them happy.

When researchers talk to people about what makes them happy, and what causes them pain, a pretty consistent set of answers emerge. For example, Robert E. Lane’s (2000) influential study showed strong links between subjective feelings of well-being and companionship (by which Lane meant family solidarity and friendship). We gain happiness through our relationships with other people. He argued, ‘it is their affection or dislike, their good or bad opinion of us, their acceptance or rejection that most influences our moods’. To all this we can add what we know of the significance of relationship and attachment in the early years of human life – particularly in the home. Lane found that once people rise above the poverty level happiness tends to lie in the quality of friendships and of family life. Increased income and the possession of more and more material goods have little impact on feelings of well-being.

Other writers have used a range of published research and have come to broadly the same conclusions. According to Richard Layard (2011), for example, when we look at happiness certain factors stand out: the quality of family relationships, financial situation, work, community and friends and health. He also argued that personal values and freedom as also key. Recent work has highlighted the importance of health (especially mental health) alongside family life and life at work (Layard with Ward 2020: 34) and the extent to which inequality creates social anxiety and social withdrawal (Wilkinson and Pickett 2018).

Looking for pathways to action. Snyder and his colleagues stressed the importance of ‘pathways thinking’. People need to view themselves as being able to generate routes to what they want. They need to be able to generate at least one, and often more, usable pathway. There is obviously an emotional dimension here, but there are also big questions about the access they have to the resources and opportunities they need. One of the classic things that pedagogues, workers and educators do in their work with young people is helping them to access and to find a path through, remote systems. This can range from dealing with social workers to making an application for housing. Another is to foster and open up networks and alternative forms of support and access.

Encouraging people to believe in themselves. Being hopeful requires believing in ourselves – particularly believing that we can make use of the pathway chosen. It helps, of course, if there are people around you who believe in you, and that you can see people making use of pathways and gaining happiness in some way.

This is one of those areas that pedagogues, workers and educators often struggle with. Just how much should we intervene? When do we step back and leave things to the individual or group concerned? We can get in the way of people taking responsibility, on the other hand, if we do not give support at times, then people may not be able to take the first few steps.

Conclusion

Hope helps us to critique the world as it is and our part in it, and not to just imagine change but also to plan it (Moltman 1967, 1971). It also allows us, and others, to ask questions of our hopes, to request evidence for our claims.

Expectation makes life good, for in expectation man can accept his whole present and find joy not only in its joy but also in its sorrow, happiness not only in its happiness but also in its pain… That is why it can be said that living without hope is like no longer living. Hell is hopelessness, and it is not for nothing that at the entrance to Dante’s hell there stand the words: ‘Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.’ (Moltmann 1967, Introduction)

Further reading and references

The new normal series

Dealing with the ‘new normal’. Offering sanctuary, community and hope to children and young people in schools and local organizations. This provides an overview of the context, and an outline of the way forward for schools and local organizations.

What is sanctuary? How can we offer it to children and young people in schools and local organizations.

Offering community to children and young people in schools and local organizations.

What is hope? How can we offer it to children and young people in schools and local organizations?

For those new to social pedagogy or to the way in which we are talking about pedagogy here there are a number of articles on infed that may be helpful.

The core processes of social pedagogy – animation, care and education – are discussed in a new article: Animate, care, educate – the core processes of social pedagogy.

Within informal education and social pedagogy, the character and integrity of practitioners are seen as central to the processes of working with others. The German notion of ‘haltung’ draws together key elements around this pivotal concern for pedagogues and informal educators. Explore this in another infed article: Haltung, pedagogy and informal education.

For an overview of developments in theory and practice: social pedagogy.

Many discussions of pedagogy make the mistake of seeing it as primarily being about teaching. Rather pedagogy needs to be explored through the thinking and practice of those educators who look to accompany learners; care for and about them; and bring learning into life. Teaching is just one aspect of their practice: What is pedagogy?

References

Andre, E. (2015). The need to talk about despair in A. T. Brei (ed). Ecology, Ethics and Hope. London: Roman and Littlefield.

Aquinas (2006). Summa Theologica, Part I-II (Pars Prima Secundae) / From the Complete American Edition. Project Gutenberg. [http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17897].

Augustine of Hippo, Enchiridion: On Faith, Hope, and Love. With a New Introduction by Thomas S. Hibbs. Washington DC.: Gateway Editions.

Bloeser, C. and Stahl, T. (2017). Hope in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 Edition). [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hope/. Retrieved May 25, 2020].

Bonneuil, C. and Fressoz, J-B. (2016). The shock of the Anthropocene: the earth, history, and us. London: Verso.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press.

Buber, M. (1958). I and Thou 2e, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark and (1947) Between Man and Man, London: Kegan Paul (new edition 2002 – London: Routledge).

Capra, F. (1996). The Web of Life. New York: Anchor.

Dewey, J. (1903). Emerson-The Philosopher of Democracy, International Journal of Ethics, 13, 4 (July 1903) pp. 405-413. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2376270. Retrieved June 9, 2020]

Dewey, J. (1915). Democracy and Education. An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: Macmillan. [Available from Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/446].

Dewey, J. (1920). Reconstruction in philosophy. New York: Henry Holt & Co. [Available from Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/446].

Doyle, M. E. and Smith, M. K. (1999). Born and Bred? Leadership, heart and informal education. London: YMCA George Williams College/Rank Foundation.

Fishman, S. and McCarthy, L (2007). John Dewey and the Philosophy and Practice of Hope. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Freire, P. (1994) Pedagogy of Hope. Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. With notes by Ana Maria Araujo Freire. Translated by Robert R. Barr. New York: Continuum.

Gallagher, M. W. and Lopez, S. J. (eds.) (2018). The Oxford Handbook of Hope. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gopnik, A. (2016). The Gardener and the Carpenter. What the new science of child development tells us about the relationship between parents and children. London: Random House.

Habermas, J. (1984). The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. I: Reason and the Rationalization of Society, T. McCarthy (trans.). Boston: Beacon. [German, 1981, vol. 1]

Habermas, J. (1987). The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. II: Lifeworld and System, T. McCarthy (trans.). Boston: Beacon. [German, 1981, vol. 2]

Hagell, A. (ed.) (2012). Changing adolescence. Social trends and mental health. Bristol: Policy Press.

Halpin, D. (2003a). Hope and Education. The role of the utopian imagination. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Halpin, D. (2003b). Hope, utopianism and educational renewal, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/hope-utopianism-and-educational-renewal/. Retrieved June 22, 2019].

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching Community. A pedagogy of hope. New York: Routledge.

Illich, I. (1974). Tools for Conviviality. London: Fontana.

Kant, I. (1787). The Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by J. M. D. Meiklejohn. Part II. [http://www.fullbooks.com/The-Critique-of-Pure-Reason11.html. Retrieved April 28, 2020].

Kant, I. (1788 | 2015). Critique of Practical Reason. Revised Edition. Translated by Mary Gregor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kant, I. (1900). Kant on Education (Ueber paedagogik). Translated by A. Churton. Boston: D.C. Heath. [http://files.libertyfund.org/files/356/0235_Bk.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012].

Lane, R. E. (2000) The Loss of Happiness in Market Economies, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Layard, R. (2011). Happiness. Lessons from a new science 2e. London: Penguin.

Layard, R. with Ward, G. (2020). Can we be Happier? Evidence and ethics. London: Pelican Books.

Lear, J. (2006). Radical Hope. Ethics in the face of cultural devastation. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Leontopoulou, S. (2020). Hope Interventions for the Promotion of Well-Being Throughout the Life Cycle, Oxford Research Encyclopedia, Education [DOI:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.765. Retrieved June 8, 2020]

MacQuarrie, J. (1978). Christian Hope. Oxford: Mowbray.

Marcel. G. (1962). Homo viator: Introduction to a metaphysic of hope. New York: Harper & Row, Harper Torch books (First published in 1951 by Victor Gollanz).

Moltmann, J. (1967). Theology of hope: On the ground and the implications of a Christian eschatology. New York: Harper & Row. Available on-line: http://www.pubtheo.com/page.asp?PID=1036.

Nietzsche, F. (1878 | 1994). Human, All Too Human. Translated by Marion Faber. London: Penguin.

Nietzsche, F. (1883–85 | 2005). Thus spoke Zarathustra.A Book for Everyone and Nobody. Translated by Graham Parkes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nouwen, H. (1975). Reaching Out. New York: Doubleday.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A classification and handbook. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pieper, J. (1997). Faith, Hope, Love. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

Rorty, R. (1979). Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton NJ.: Princton University Press.

Rorty, R. (1999). Philosophy and Social Hope. London: Penguin.

Scrutton. R. (2001). Kant. A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seligman, M E P. (2003). Authentic Happiness. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Smith, M. K. (2012). ‘What is pedagogy?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-pedagogy/. Retrieved: March 16, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2019a). Animation, care and education – the core processes of social pedagogy, Developing Learning. [https://infed.org/mobi/animate-care-educate-the-core-processes-of-social-pedagogy/. Retrieved: May 28, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2019b). Haltung, pedagogy and informal education, infed.org. [https://infed.org/mobi/haltung-pedagogy-and-informal-education/. Retrieved: April 28, 2020].

Snyder, C. R. (1994). The Psychology of Hope. You can get there from here. New York: Free Press.

Snyder, C.R. (2000). Hypothesis: There is hope, in C.R. Snyder (ed.), Handbook of Hope Theory, Measures and Applications. San Diego: Academic Press.

Snyder, C. R., Rand, Kevin L., Sigmon, D. R. (2002). ‘Hope theory: A member of the positive psychology family’ in C. R. Snyder and S. J. Lopez, Shane J. (eds.). (2002). Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. pp. 257-276. Available: http://teachingpsychology.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/hope-theory.pdf. Retrieved April 2, 2016].

Solnit, R. (2016). Hope in the Dark. Untold histories, wild possibilities. 3e. Edinburgh: Canongate. [Page numbers refer to the epub version].

Tillich, P. (1952). The Courage to Be. New Haven CT.: Yale University Press.

Warnock, M. (1986). The Education of the Emotions. In D. Cooper (ed.) Education, values and the mind. Essays for R. S. Peters. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul.

Wilkinson, R and Pickett, K. (2018). The Inner Level. How more equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and improve everyone’s well-being. London: Penguin.

Yohani, S. C. (2008). Creating an Ecology of Hope: Arts-based Interventions with Refugee Children, Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 25:309-323. [DOI 10.1007/s 10560-008-0129-x. Retrieved June 11, 2020]

Young, K. (2006). The Art of Youth Work. 2e. Lyme Regis: Russell House Publishing.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. London: Profile Books. [Pages details refer to Adobe digital numbering].

Acknowledgements: The material here on sanctuary and hope grew out of some work undertaken by Michele Erina Doyle and myself on Christian youth work for the Joseph Rank Trust some years back (see Doyle and Smith 1999) – and from recent work with Giles Barrow and others on the development of the role of the pedagogue within specialist education.

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2020). What is hope? How can we ofer it to children and young people in schools and local organizations? The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-hope?-how-can-we-offer-it-to-children-and-young-people-in-schools-and-local-organizations?/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K Smith 2020