Pedagogy is often, wrongly, seen as ‘the art and science of teaching’. Mark K. Smith explores the origins and development of pedagogy and finds a different story – accompanying people on their journeys. Teaching is just one part of what they do.

contents: introduction · the nature of education · pedagogues and teachers · the growing focus on teaching · the re-emergence of pedagogy · pedagogy as accompanying, caring for and bringing learning to life · the process of pedagogy · conclusion · further reading and references · acknowledgements · how to cite this piece

See also: haltung, pedagogy and informal education

A definition for starters:

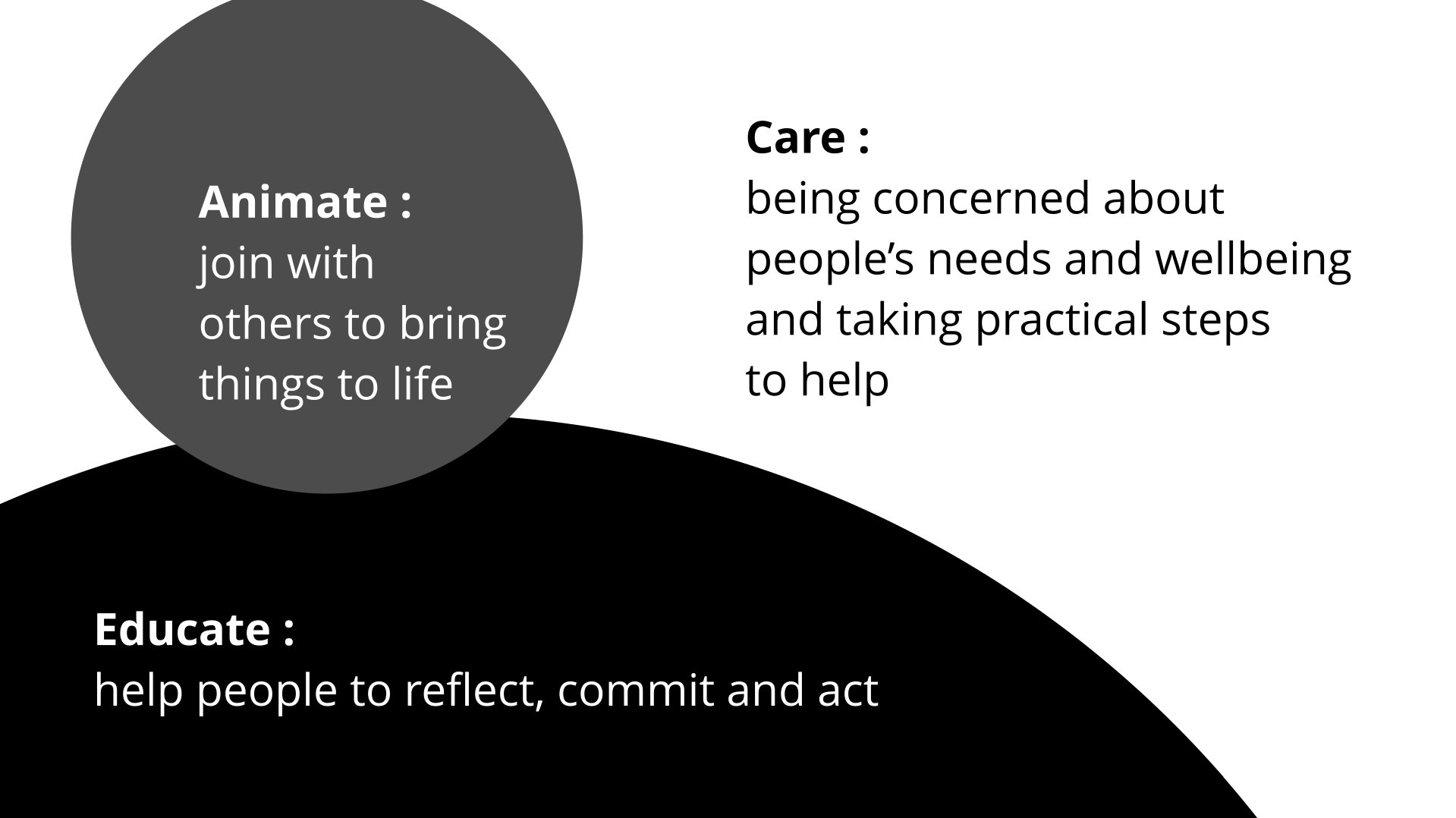

Pedagogy is a way of being and interacting that involves:

• joining with others to bring flourishing and relationship to life (animation)

• being concerned about their, and other’s, needs and wellbeing, and taking practical steps to help (caring);

and

• encouraging reflection, commitment and change (education).

See Animate, care, educate.

Introduction

In recent years interest has grown in ‘pedagogy’ within English-language discussions of education. The impetus has come from different directions. There have been those like Paulo Freire seeking a ‘pedagogy of the oppressed’ or ‘critical pedagogy’; practitioners wanting to rework the boundaries of care and education via the idea of social pedagogy; and, perhaps most significantly, governments wanting to constrain the activities of teachers by requiring adherence to preferred ‘pedagogies’.

A common way of approaching pedagogy is as the art and science (and maybe even craft) of teaching. As we will see, viewing pedagogy in this way both fails to honour the historical experience, and to connect crucial areas of theory and practice. Here we suggest that a good way of exploring pedagogy is as the process of accompanying learners; caring for and about them; and bringing learning into life.

The nature of education

Our starting point here is with the nature of education. Unfortunately, it is easy to confuse education with schooling. Many think of places like schools or colleges when seeing or hearing the word. They might also look to particular jobs like teacher or tutor. The problem with this is that while looking to help people learn, the way a lot of teachers work isn’t necessarily something we can properly call education.

Often teachers fall or are pushed, into ‘schooling’ – trying to drill learning into people according to some plan often drawn up by others. Paulo Freire (1972) famously called this ‘banking’ – making deposits of knowledge. It can quickly descend into treating learners like objects, things to be acted upon rather than people to be related to. In contrast, to call ourselves ‘educators’ we need to look to acting with people rather on them.

Education is a deliberate process of drawing out learning (educere), of encouraging and giving time to discovery. It is an intentional act. At the same time, it is, as John Dewey (1963) put it, a social process – ‘a process of living and not a preparation for future living’. As well being concerned with learning that we set out to encourage – a process of inviting truth and possibility – it is also based on certain values and commitments such as respect for others and for truth. Education is born, it could be argued, of the hope and desire that all may share in life and ‘be more’.

For many concerned with education, it is also a matter of grace and wholeness, wherein we engage fully with the gifts we have been given. As Pestalozzi constantly affirmed, education is rooted in human nature; it is a matter of head, hand and heart (Brühlmeier 2010). We find identity, meaning, and purpose in life ‘through connections to the community, to the natural world, and to spiritual values such as compassion and peace’ (Miller 2000).

To educate is, in short, to set out to create and sustain informed, hopeful and respectful environments where learning can flourish. It is concerned not just with ‘knowing about’ things, but also with changing ourselves and the world we live in. As such education is a deeply practical activity – something that we can do for ourselves (what we could call self-education), and with others. This is a process carried out by parents and carers, friends and colleagues, and specialist educators.

It is to the emergence of the last of these in ancient Greece that we will now turn as they have become so much a part of the way we think about, and get confused by, the nature of pedagogy.

Pedagogues and teachers in ancient Greek society

Within ancient Greek society, there was a strong distinction between the activities of pedagogues (paidagögus) and subject teachers (didáskalos). The first pedagogues were slaves – often foreigners and the ‘spoils of war’ (Young 1987). They were trusted and sometimes learned members of rich households who accompanied the sons of their ‘masters’ in the street, oversaw their meals etc., and sat beside them when being schooled. These pedagogues were generally seen as representatives of their wards’ fathers and literally ‘tenders’ of children (pais plus agögos, a ‘child-tender’). Children were often put in their charge at around 7 years and remained with them until late adolescence.

The roles and relationships of pedagogues

Plato talks about pedagogues as ‘men who by age and experience are qualified to serve as both leaders (hëgemonas) and custodians (paidagögous)’ of children (Longenecker 1983: 53). Their role varied but two elements were common (Smith 2006). The first was to be an accompanist or companion – carrying books and bags, and ensuring their wards were safe. The second and more fundamental task concerning boys was to help them learn what it was to be men. This they did by a combination of example, conversation and disciplining. Pedagogues were moral guides who were to be obeyed (Young 1987: 156)

The pedagogue was responsible for every aspect of the child’s upbringing from correcting grammar and diction to controlling his or her sexual morals. Reciting a pedagogue’s advice, Seneca said, “Walk thus and so; eat thus and so, this is the proper conduct for a man and that for a woman; this for a married man and that for a bachelor’. (Smith 2006: 201)

Employing a pedagogue was a custom that went far beyond Greek society. Well-to-do Romans and some Jews placed their children in the care and oversight of trusted slaves. As Young (1987) notes, it was a continuous (and ever-widening) practice from the fifth century B.C. until late into imperial times (quoted in Smith 2006). He further reports that brothers sometimes shared one pedagogue in Greek society. In contrast, in Roman society, there were often several pedagogues in each family, including female overseers for girls. This tradition of accompanying and bag carrying could still be found in more recent systems of slavery such as that found in the United States – as Booker T Washington recounted in his autobiography Up from Slavery (1963).

The relation of the pedagogue to the child is a fascinating one. It brings new meaning to Friere’s (1972) notion of the ‘pedagogy of the oppressed’ – this was the education of the privileged by the oppressed. It was a matter that, according to Plato, did not go unnoticed by Socrates. In a conversation between Socrates and a young boy Lysis, Socrates asked, ‘Someone controls you?’ Lysis replied, ‘Yes, he is my tutor [or pedagogue] here.’ ‘Is he a slave?’ Socrates queried. ‘Why, certainly; he belongs to us,’ responded Lysis, to which Socrates mused, ‘What a strange thing, I exclaimed; a free person controlled by a slave!’ (Plato 1925, quoted by Smith 2006).

Pedagogues and teachers

Moral supervision by the pedagogue (paidagogos) was significant in terms of status

He was more important than the schoolmaster because the latter only taught a boy his letters, but the paidagogos taught him how to behave, a much more important matter in the eyes of his parents. He was, moreover, even if a slave, a member of the household, in touch with its ways and with the father’s authority and views. The schoolmaster had no such close contact with his pupils. (Castle 1961: 63-4)

However, because both pedagogues and teachers were of relatively low status they were could be disrespected by the boys. There was a catch here. As the authority and position of pedagogues flowed from the head of the household, and their focus was more on life than ‘letters’, they had advantages over teachers (didáskalos).

The distinction between teachers and pedagogues, instruction and guidance, and education for school or life was a feature of discussions around education for many centuries. It was still around when Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) explored education. In On Pedagogy (Über Pädagogik) first published in 1803, he talked as follows:

Education includes the nurture of the child and, as it grows, its culture. The latter is firstly negative, consisting of discipline; that is, merely the correcting of faults. Secondly, culture is positive, consisting of instruction and guidance (and thus forming part of education). Guidance means directing the pupil in putting into practice what he has been taught. Hence the difference between a private teacher who merely instructs, and a tutor or governor who guides and directs his pupil. The one trains for school only, the other for life. (Kant 1900: 23-4)

The question we need to ask, then, is how did ‘pedagogy’ become focused on teaching?

The growing focus on teaching

In Europe, concern with the process and content of teaching and instruction developed significantly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was, however, part of a movement that dated from 300-400 years earlier. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries we see, for example:

- A growing literature about instruction, and method, aimed at schoolteachers.

- The grouping together of different areas of knowledge in syllabi which set out what was to be instructed.

- A focus on the organisation, and development, of schools (Hamilton 1999: 138).

There was a ‘the separation of the activity of “teaching” from the activity of defining “that which is taught” (ibid: 139). This led in much of continental Europe to a growing interest in the process of teaching and the gathering together of examples, guidance and knowledge in the form of what became known as didactics.

Didactics

One of the important landmarks here was the publication of John Amos Comenius’s book The Great Didactic [Didactica Magna] (first published in Czech in 1648, Latin in 1657 and English in 1896). For Comenius,

the fundamental aims of education generate the basic principle of Didactica Magna, omnis, omnia, omnino – to teach everything to everybody thoroughly, in the best possible way, Comenius believed that every human being should strive for perfection in all that is fundamental for life and do this as thoroughly as possible…. Every person must strive to become (l) a rational being, (2) a person who can rule nature and him or herself, and (3) a being mirroring the creator. (Gundem 1992: 53)

He developed sets of rules for teaching and set out basic principles. His fundamental conclusions, according to Gundem (1992: 54) remain valid:

- Teaching must be in accordance with the student’s stage of development…

- All learning happens through the senses…

- One should proceed from the specific to the general, from what is easy to the more difficult, from what is known to the unknown.

- Teaching should not cover too many subjects or themes at the same time.

- Teaching should proceed slowly and systematically. Nature makes no jumps. (op. cit.)

Following Kant and Comenius, another significant turning point in thinking about teaching came through the growing influence of one of Kant’ successors in the Chair of Philosophy at Königsberg University: Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776-1841).

Theories of teaching

As Hamilton (1999: 143) has put it, Herbart sought to devise, from first principles, an educational system and thus worked towards a general theory of pedagogics (see, for example, Allgemeine pädagogik – General Pedagogics, 1806 and Umriss Pädagogischer Vorlesungen, 1835 – Plan of Lectures on Pedagogy and included in Herbart 1908).

At the centre of his theory of education and of schooling is the idea of ‘educational teaching’ or ‘educating instruction’ (erzieinder Unterricht). Hilgenheger (1993: 651-2) makes the following observations:

Like practical and theoretical educationalists before him, Herbart also makes a distinction between education (Latin: educatio) and teaching (Latin: instructio). ‘Education’ means shaping the development of character with a view to the improvement of man. ‘Teaching’ represents the world, conveys fresh knowledge, develops existing aptitudes and imparts useful skills….

Before Herbart, it was unusual to combine the concepts of ‘education’ and ‘teaching’. Consequently, questions pertaining to education and teaching were initially pursued independently… Herbart… took the bold step of ‘subordinating’ the concept of ‘teaching’ to that of ‘education’ in his educational theory. As he saw it, external influences, such as the punishment or shaming of pupils, were not the most important instruments of education. On the contrary, appropriate teaching was the only sure means of promoting education that was bound to prove successful.

In Herbart’s own words, teaching is the ‘central activity of education’.

What Herbart and his followers achieved with this was to focus consideration of instruction and teaching (didactics) around schooling rather than other educational settings (Gundem 2000: 239-40). Herbart also turned didactics ‘into a discipline of its own’ – extracting it from general educational theory (op. cit.). Simplified and rather rigid versions of his approach grew in influence with the development of mass schooling and state-defined curricula.

This approach did not go unchallenged at the time. There were those who argued that teaching should become part of the human rather than ‘exact’ sciences (see Hamilton 1999: 145-6). Rather than seeking to construct detailed systems of instruction, the need was to explore the human experience of teaching, learning and schooling. It was through educational practice and reflection upon it (‘learning by doing’) and exploring the settings in which it happens that greater understanding would develop. In Germany, some of those arguing against an over-focus on method and state control of curricula looked to social pedagogy with its focus on community and democracy (see below).

Education as a science

These ideas found their way across the channel and into English-language books and manuals about teaching – especially those linked to Herbart. Perhaps the best-known text was Alexander Bain’s Education as a Science (first published in 1879 – and reprinted 16 or more times over the next twenty years). However, its influence was to prove limited. Brian Simon (1981) in an often-cited chapter ‘Why no pedagogy in England?’, argued that with changes in schooling in the latter years of the nineteenth century and growing government intervention there was much less emphasis upon on intellectual growth and much more on containment. In addition the psychology upon which it was based was increasingly called into question. Simon (1981: 1) argued:

The most striking aspect of current thinking and discussion about education is its eclectic character, reflecting deep confusion of thought, and of aims and purposes, relating to learning and teaching – to pedagogy.

As a result, education as a science – and its study – is ‘still less a “science” and has little prestige (ibid.: 2). He continued, ‘The dominant educational institutions of this country have had no concern with theory, its relation to practice, with pedagogy’ (he defined pedagogy as the science of teaching). More recently, educationalists like Robin Alexander (2004: 11) have argued that it is the prominence of the curriculum in English schooling led to pedagogy (as the process of teaching) remaining in a subsidiary position. This was especially so in the arguments around introducing a National Curriculum in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (established in the Education Reform Act 1988) – and the implementation of the curriculum in its first twenty years. The focus was upon ‘delivering’ certain content and testing to see whether it had been retained.

The re-emergence of pedagogy

In continental Europe interest in didactics and pedagogy remained relatively strong and there were significant debates and developments in thinking (see Gundem 2000: 241-59). Relatively little attention was paid to pedagogy in Britain and North America until the 1970s and early 1980s. But this changed.

Writing about pedagogy

Initially, interest in pedagogy was reawakened by the decision of Paulo Freire to name his influential book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (first published in English in 1970). The book became a key reference point on many education programmes in higher education and central to the establishment of explorations around critical pedagogy. It was followed by another pivotal text – Basil Bernstein’s (1971) ‘On the classification and framing of educational knowledge’. He drew upon developments in continental debates. He then placed them in relation to the different degrees of control people had over their lives and educational experience according to their class position and cultures. Later he was to look at messages carried by different pedagogies (Bernstein 1990). Last, we should not forget the influence of Jerome Bruner’s discussion of the culture of education (1996). He argued that teachers need to pay particular attention to the cultural contexts in which they are working and of the need to look to ‘folk theories’ and ‘folk pedagogies’ (Bruner 1996: 44-65). ‘Pedagogy is never innocent’, he wrote, ‘It is a medium that carries its own message’ (op. cit.: 63).

Pedagogy as a means of control

A fundamental element in the growing interest in pedagogy was a shift in government focus in education in England. As well as seeking to control classroom activity via the curriculum there was a movement to increase the monitoring of classroom activity via regular scrutiny by senior leadership teams and a much enhanced Ofsted evaluation schedule for lesson observation (Ofsted 2011; 2012). Key indicators for classroom observation included a variety of learning styles addressed, pace, dialogue, the encouragement of independent learning and so on (Ofsted 2011). A number of popular guides appeared to help teachers on their way – perhaps the best received of which was The Perfect Ofsted Lesson (Beere 2010). While the language sounded progressive, and the practices promoted had merit, the problem was the framework in which it was placed. It was, to use Alexander’s words, ‘pedagogy of compliance’. ‘You may be steeped in educational research and/or the accumulated wisdom of 40 years in the classroom, but unless you defer to all this official material your professional judgements will be ‘uninformed”’ (Alexander 2004: 17)

Pedagogy or didactics

Unfortunately, the way pedagogy was being defined still looked back to the focus on teaching that Herbart argued for nearly 200 years ago. For example, the now-defunct General Teaching Council for England, described it thus:

Pedagogy is the stuff of teachers’ daily lives. Put simply it’s about teaching. But we take a broad view of teaching as a complex activity, which encompasses more than just ‘delivering’ education. Another way to explain it is by referring to:

- the art of teaching – the responsive, creative, intuitive part

- the craft of teaching – skills and practice

- the science of teaching – research-informed decision making and the theoretical underpinning.

It is also important to remember that all these are grounded in ethical principles and moral commitment – teaching is never simply an instrumental activity, a question just of technique.

While we can welcome the warnings against viewing teaching as an instrumental activity – whether it is satisfactory to describe it as pedagogy is a matter for some debate. Indeed Hamilton (1999) has argued that much of what passes for pedagogy in UK education debates is better understood as didactics. We can see this quickly when looking at the following description of didactics from Künzli (1994 quoted in Gundem 2000: 236).

Simplified we may say that the concerns of didactics are: what should be taught and learnt (the content aspect); how to teach and learn (the aspects of transmitting and learning): to what purpose or intention something should he taught and learnt (the goal/aims aspect

Perhaps because the word ‘didactic’ in the English language is associated with dull, ‘jug and mug’ forms of teaching, those wanting to develop schooling tended to avoid using it. Yet, in many respects, key aspects of what is talked about today as pedagogy in the UK and North America is better approached via this continental tradition of didactics.

Pedagogy as accompanying, caring for (and about) and bringing learning to life

A third element in the turn to pedagogy flowed from concerns in social work and youth work in the UK that the needs of many children were not being met by existing forms of practice and provision. Significantly, a number of practitioners and academics looked to models of practice found in continental Europe and Scandinavia and focused, in particular, on the traditions of social pedagogy (see Lorenz 1994; Smith 1999; Cameron 2004 and Cameron and Moss 2011). In Scotland, for example, there was discussion of the ‘Scottish pedagogue’ (after the use of the term ‘Danish pedagogue) (Cohen 2008). In England, various initiatives and discussions emerged around reconceptualising working with children in care as social pedagogy and similarly the activities of youth workers, teachers, mentors and inclusion workers within schools (see, for example, Kyriacou’s work 2010). Significantly, much of this work bypassed the English language discussion of pedagogy – which was probably an advantage in some ways. However, it also missed just how much work in the UK was undertaken by specialist pedagogues drawing upon thinking and practice well-known to social pedagogues but whose identity has been formed around youth work, informal and social education and community learning and development (Smith 1999, 2009).

If we look to these traditions we are likely to re-appreciate pedagogy. Here I want to suggest that what comes to the fore is a focus on flourishing and of the significance of the person of the pedagogue (Smith and Smith 2008). In addition, three elements things out about the processes of the current generation of specialist pedagogues. First, they are heirs to the ancient Greek process of accompanying. Second, their pedagogy involves a significant amount of helping and caring for. Third, they are engaged in what we can call ‘bringing learning to life’. Woven into those processes are theories and beliefs that we also need to attend to (see Alexander 2000: 541). To reword and add to Robin Alexander (2004: 11) pedagogy can be approached as what we need to know, the skills we need to command, and the commitments we need to live in order to make and justify the many different kinds of decisions needed to be made.

A focus on flourishing

The first and obvious thing to say is that pedagogues have a fundamentally different focus to subject teachers. Their central concern is with the well-being of those they are among and with. In many respects, as Kerry Young (1999) has argued with regard to youth work, pedagogues are involved for much of the time in an exercise in moral philosophy. Those they are working with are frequently seeking to answer in some way profound questions about themselves and the situations they face. At root these look to how people should live their lives: ‘what is the right way to act in this situation or that; of what does happiness consist for me and for others; how should I to relate to others; what sort of society should I be working for?’ (Smith and Smith 2008: 20). In turn, pedagogues need to have spent some time reflecting themselves upon what might make for flourishing and happiness (in Aristotle’s terms eudaimonia).

In looking to continental concerns and debates around pedagogy, a number of specialist pedagogues have turned to the work of Pestalozzi and to those concerned with more holistic forms of practice (see, for example, Cameron and Ross 2011). As Brühlmeier (2010: 5) has commented, ‘Pestalozzi has shown that there is more to [education] than attaining prescribed learning outcomes; it is concerned with the whole person, with their physical, mental and psychological development’. Learning is a matter of head, hand and heart. Heart here is a matter of, ‘ spirit– the passions that animate or move us; moral sense or conscience– the values, ideals and attitudes that guide us; and being– the kind of person we are, or wish to be, in the world (Doyle and Smith 1999: 33-4).

The person of the pedagogue

This is a way of working that is deeply wrapped up with the person of the pedagogue; their disposition toward flourishing, truth and justice (what many with the tradition of social pedagogy call haltung); and their readiness and ability to reflect, make judgements and respond (Smith and Smith 2008: 15). They need to be experienced as people who can be trusted, respected and turned to.

[W]e are called upon to be wise. We are expected to hold truth dearly, to be sincere and accurate… There is also, usually, an expectation that we have a good understanding of the subjects upon which we are consulted, and that we know something about the way of the world. We are also likely to be approached for learning and counsel if we are seen as people who have the ability to come to sound judgements, and to help others to see how they may act for the best in different situations, and how they should live their lives. (Smith and Smith 2008: 19)

At one level, the same could be said of a ‘good’ subject teacher in a school. As Palmer (1998: 10) has argued, ‘good teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher’ (emphasis in the original). However, the focus of pedagogues frequently takes them directly into questions around identity and integrity. This then means that their authenticity, and the extent to which they are experienced as wise, are vital considerations.

Accompanying

The image of Greek pedagogues walking alongside their charges, or sitting with them in classrooms is a powerful one. It connects directly with the experiences of many care workers, youth workers, support workers and informal educators. They spend a lot of time being part of other people’s lives – sometimes literally walking with them to some appointment or event, or sitting with them in meetings and sessions. They also can be a significant person for someone over a long period of time – going through difficulties and achievements with them. Green and Christian (1998: 21) have described this as accompanying.

The greatest gift that we can give is to ‘be alongside’ another person. It is in times of crisis or achievement or when we have to manage long-term difficulties that we appreciate the depth and quality of having another person to accompany us. In Western society at the end of the twentieth century this gift has a fairly low profile. Although it is pivotal in establishing good communities its development is often left to chance and given a minor status compared with such things as management structure and formal procedures. It is our opinion that the availability of this sort of quality companionship and support is vital for people to establish and maintain their physical, mental and spiritual health and creativity.

It is easy to overlook the sophistication of this relationship and the capacities needed to be ‘alongside another’. It entails ‘being with’ – and this involves attending to the other.

It is our relationship with a young person upon which most of our work, as a practitioner, hinges. And this is a relationship that can ‘develop only when the persons involved pay attention to one another’ (Barry and Connolly 1986: 47). What effective workers with individual young people do is highly skilled work, drawing on, through different stages in the process, a range of diverse roles and capacities. Done well the practitioner moves seamlessly through the stages, but the unifying core is the relationship between young person and the worker. (Collander-Brown 2005: 33)

Pedagogues have to be around for people; in places where they are directly available to help, talk and listen. They also have to be there for people: ready to respond to the emergencies of life – little and large (Smith and Smith 2008:18).

Caring for and caring about

In recent years our understanding of what is involved in ‘caring’ has been greatly enhanced by the work of Nel Noddings. She distinguishes between caring-for and caring-about. Caring-for involves face-to-face encounters in which one person attends directly to the needs of another. We learn first what it means to be cared-for. ‘Then, gradually, we learn both to care for and, by extension, to care about others’ (Noddings 2002: 22). Such caring-about, Noddings suggests, can be seen as providing the foundation for our sense of justice.

Noddings then argues that caring relations are a foundation for pedagogical activity (by which she means teaching activity):

First, as we listen to our students, we gain their trust and, in an on-going relation of care and trust, it is more likely that students will accept what we try to teach. They will not see our efforts as “interference” but, rather, as cooperative work proceeding from the integrity of the relation. Second, as we engage our students in dialogue, we learn about their needs, working habits, interests, and talents. We gain important ideas from them about how to build our lessons and plan for their individual progress. Finally, as we acquire knowledge about our students’ needs and realize how much more than the standard curriculum is needed, we are inspired to increase our own competence (Noddings 2005).

For many of those concerned with social pedagogy, it is place where care and education meet – one is not somehow less than the other (Cameron and Moss 2011). For example, in Denmark ‘care’ can be seen as one of the four central areas that describe the pedagogical tasks:

Care (take care of), socialisation (to and in communities), formation (for citizenship and democracy) and learning (development of individual skills)… [T]he ”pedagogical” task is not simply about development, but also about looking after… [P]edagogues not only put the individual child in the centre, but also take care of the interests of the community. (BUPL undated)

What we have here is a helping relationship. It ‘involves listening and exploring issues and problems with people; and teaching and giving advice; and providing direct assistance; and being seen as people of integrity’. (Smith and Smith 2008: 14)

Bringing learning to life

In talking about pedagogy as a process of bringing learning to life I want to focus on three aspects. Pedagogy as:

- Animation – bringing ‘life’ into situations. This is often achieved by offering new experiences.

- Reflection – creating moments and spaces to explore lived experience.

- Action – working with people so that they are able to make changes in their lives.

Animation. In their 1997 book Working with experience: Animating learning David Boud and Nod Miller link ‘animating’ to ‘learning’ because of the word’s connotations: to give life to, to quicken, to vivify, to inspire. They see the job of animators (animateurs) to be that of ‘acting with learners, or with others, in situations where learning is an aspect of what is occurring, to assist them to work with their experience’ (1997: 7). It is a pretty good description of what many social pedagogues, youth workers and informal educators do for much of the time. They work with people on situations and relationships so that they are more stimulating and satisfying. However, they also look to what Dewey (1916) described as enlarging experience and to making it more vivid and inspiring (to use Boud and Miller’s words). They encourage people to try new things and provide opportunities that open up fresh experiences

Reflection. Within these fields of practice, there has been a long-standing tradition of looking to learning from experience and, thus, to encouraging reflection (see, for example, Smith 1994). Conversation is central to the practice of informal educators and animators of community learning and development. With this has come a long tradition of starting and staying with the concerns and interests of those they are working with, while at the same time creating moments and spaces where people can come to know themselves, their situations and what is possible in their lives and communities.

Action. This isn’t learning that stops at the classroom door, but is focused around working with people so that they can make changes in their lives – and in communities. As Lindeman put it many years ago, this is education as life. Based in responding to ‘situations, not subjects’ (1926: 4-7), it involves a committed and action-oriented form of education. This:

… is not formal, not conventional, not designed merely for the purpose of cultivating skills, but… something which relates [people] definitely to their community… It has for one of its purposes the improvement of methods of social action… We are people who want change but we want it to be rational, understood. (Lindeman 1951: 129-130)

In short, this is a process of joining in with people’s lives and working with them to make informed and committed change.

The process of pedagogy – a summary

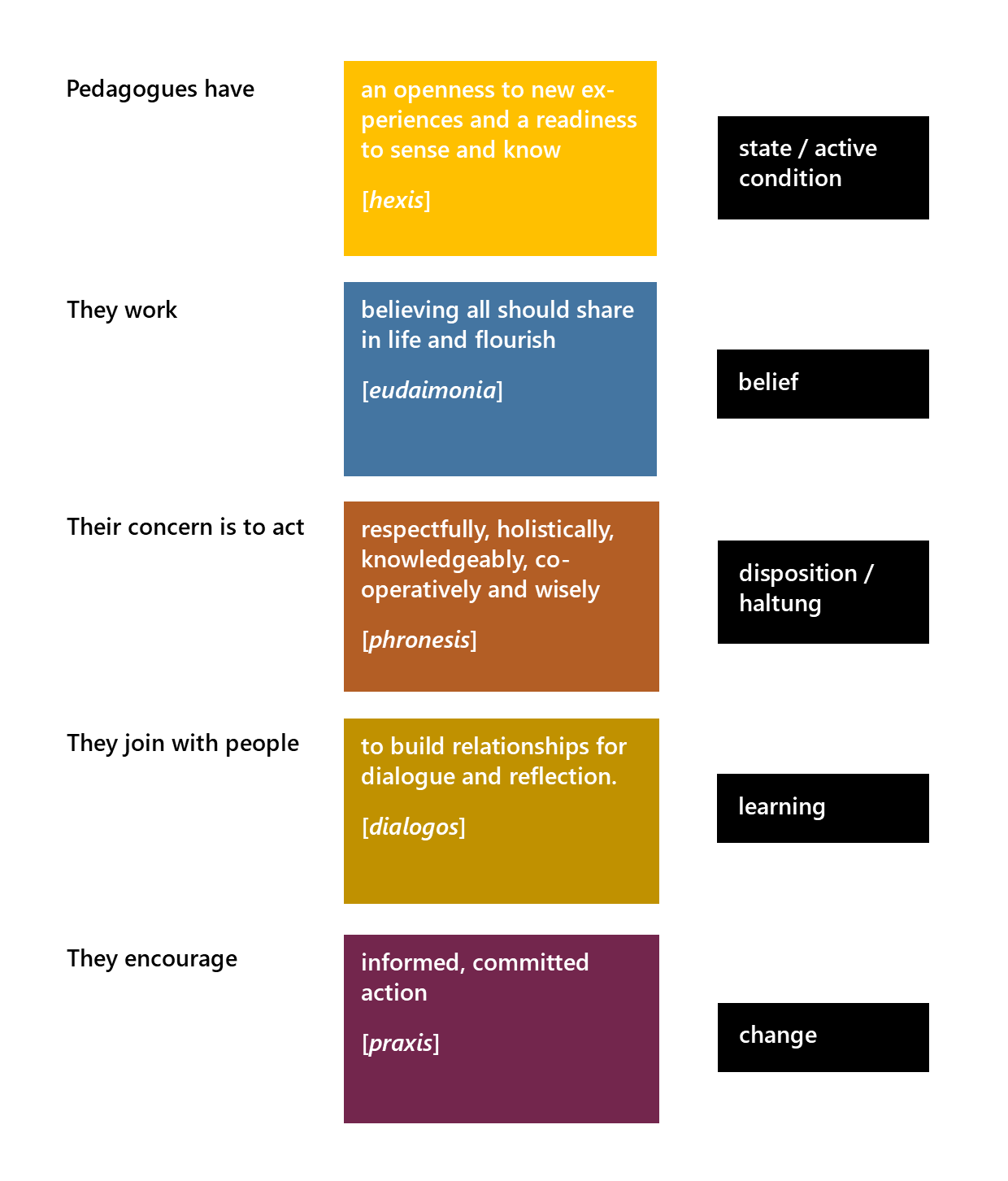

In Aristotle’s terms pedagogy comprises a leading idea (eidos); what we are calling haltung or disposition (phronesis – a moral disposition to act truly and rightly); dialogue and learning (interaction) and action (praxis – informed, committed action) (Carr and Kemmis 1986; Grundy 1987). In the following summary, we can see many of the elements we have been exploring here (Smith 2019).

To this, we need to add what Aristotle discusses as hexis – a readiness to sense and know. This is a state – or what Joe Sachs (2001) talks about as an ‘active condition’. It allows us to take a step forward – both in terms of the processes discussed above, and in what we might seek to do when working with learners and participants. Such qualities can be seen as being at the core of the haltung and processes of pedagogues and informal educators. There is a strong emphasis upon being in touch with feelings, of attending to intuitions and seeking evidence to confirm or question what we might be sensing. A further element is also present – a concern not to take things for granted or at their face value (See, also, Pierre Bourdieu on education, Bourdieu 1972|1977: 214 n1).

Conclusion

The growing interest in social pedagogy and specialist pedagogues in some countries, when put alongside developments in thinking about the nature of learning –means that we are at one of those moments where there might be movement around how the term is used in English-language contexts. Here I just want to highlight three areas of debate:

- Is pedagogy tied to age?

- Can the notion of pedagogy be unhooked from the discourse of schooling and returned to something more like its Greek origins?

- Where are we to stand in the debate around whether it is an art, science or craft?

Just for children?

As we have seen, etymologically, ‘pedagogy’ is derived from the Greek paidag?ge? meaning literally, ‘to lead the child’ or ‘tend the child’. In common usage, it is often used to describe practice with children. Indeed, much of the work that ‘social pedagogy’ has been used to describe has been with children and young people. While Paulo Freire (1972) and others talked about pedagogy in relation to working with adults, there are plenty who argue that it cannot escape its roots is bound up with practice with children. For example, Malcolm Knowles (1970) was convinced that adults learned differently to children – and that this provided the basis for a distinctive field of enquiry. He, thus, set andragogy – the art and science’ of helping adults learn – against pedagogy. While we might question whether children’s processes of learning differ significantly from adults, it is the case that educators tend to approach them differently and employ contrasting strategies. The question we are left with is whether it is more helpful to restrict usage of the term ‘pedagogy’ to practice with children or whether it can be applied across the age range? There is a fairly strong set of arguments for the former position – the word’s origin; organisational and policy concerns that tend separate children (up to 18 years old) from adults; and current usage of the term. Against restricting it to children are that learning isn’t easily divided along child/adult lines; and via writers like Freire, it is possible to draw on traditions of thinking and practice regarding pedagogy that apply to both adults and children. While recognizing the strength of the arguments for using ‘pedagogy to describe practice across the lifespan, there may be pragmatic reasons for retaining a focus on children and young people. In part, this flows from the organizational context of schooling, welfare and education service; in part from etymology.

Can pedagogy be unhooked from schooling?

There are also questions around the extent to which, in the English language at least, the notion of pedagogy has been tainted by its association with schooling. When we use the term to what extent are we importing assumptions and practices that we may not intend? ‘At the heart of this language’, wrote as Street and Street (1991: 163), ‘in contemporary society, there is a relentless commitment to instruction’. While didactics may be the most appropriate or logical way of thinking about the processes, ideas and commitments involved in teaching, there is some doubt that the term ‘pedagogy’ can take root in any sensible way in debates where English is the dominant language.

In Britain and Ireland there is some hope that pedagogy can be rescued. That possibility rests largely on the extent to which social pedagogy and its associated forms become established – especially in social work and community learning and development. If this professional identity takes root, and academic training programmes follow, then there is a chance that a counter-culture will grow and offer a contrasting set of debates. There is some evidence that this is beginning to happen with jobs with the social pedagogue title appearing in both care settings and schools, and new degree programmes being established in the UK.

Art, science or craft?

While there are many who argue that pedagogy can be approached as a science (see, for example, the discussions in Kornbeck and Jensen 2009), others look to it more as an art or craft. Donald Schön’s (1983) work on reflective practice and his critique of the sort of ‘technical rationality’ that has been crudely employed within more ‘scientific’ approaches to practice has been influential. Elliot Eisner’s (1979) view of education and teaching as improvisatory and having a significant base in process has also been looked to. He argued that the ability to reflect, imagine and respond involves developing ‘the ideas, the sensibilities, the skills, and the imagination to create work that is well proportioned, skilfully executed, and imaginative, regardless of the domain in which an individual works’. ‘The highest accolade we can confer upon someone’, he continued, ‘is to say that he or she is an artist whether as a carpenter or a surgeon, a cook or an engineer, a physicist or a teacher’

The idea of pedagogy and teaching as a craft got a significant boost in the 1990s through the work of Brown and McIntyre (1993). Their research showed, that day-to-day, the work of experienced teachers had a strong base in what is best described as a ‘craft knowledge’ of ideas, routines and situations. In much the same way that C Wright Mills talked of ‘intellectual craftsmanship’, so we can think of pedagogy as involving certain commitments and processes.

Scholarship is a choice of how to live as well as a choice of career; whether he knows it or not, the intellectual workman forms his own self as he works toward the perfection of his craft; to realize his own potentialities, and any opportunities that come his way, he constructs a character which has as its core the qualities of a good workman.

What this means is that you must learn to use your life experience in your intellectual work: continually to examine and interpret it. In this sense craftsmanship is the center of yourself and you are personally involved in every intellectual product upon which you work. (Mills 1959: 196)

There is a significant overlap between what Schön talks about as artistry and Mills as craftsmanship – and many specialist pedagogues within the UK would be much more at home with these ways of describing their activities, than as a science. Certainly, it is difficult to see how the environments or conditions in which pedagogues work can be measured and controlled in the same way that would be normal in what we might call ‘science’. It is also next to impossible on a day-to-day basis to assess in a scientific way the different influences on an individual and group, and the extent to which the work of the pedagogue made a difference.

We need to move discussions of pedagogy beyond seeing it as primarily being about teaching – and look at those traditions of practice that flow from the original pedagogues in ancient Greece. We have much to learn from the thinking and practice of specialist pedagogues who look to accompany learners, care for and about them, and bring learning into life. Teaching is just one aspect of their practice.

Further reading

Brühlmeier, A. (2010). Head, Heart and Hand. Education in the spirit of Pestalozzi. Cambridge: Sophia Books.

Hamilton, D. (1999). ‘The pedagogic paradox (or why no didactics in England?)’, Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 7:1, 135-152. [http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14681369900200048. Retrieved: February 10, 2012].

Smith, H., & Smith, M. (2008). The art of helping others: Being around, being there, being wise. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

References

Alexander, R. (2000). Culture and Pedagogy. International comparisons in primary education. Oxford: Blackwell.

Alexander, Robin (2008). Essays on Pedagogy. London: Routledge.

Atherton, C. (1998). ‘Children, animals, slaves and grammar’, in Y. L. Too & N. Livingstone (eds.) Pedagogy and Power: rhetorics of classical learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barry, W. A. and Connolly, W.J. (1986). The Practice of Spiritual Direction. New York: Harper and Collins.

Beere, J. (2010). The perfect Ofsted lesson. Bancyfelin: Crown House Publishing.

Bernstein, B. (1971). ‘On the classification and framing of educational knowledge’, in M. F. D. Young (ed.) Knowledge and Control: new directions for the sociology of knowledge. London: Collier-Macmillan.

Bernstein, B. (1990). The structuring of pedagogical discourse. Class, codes and control, Volume 4. London: Routledge.

Board of Education (1944). Teachers and Youth Leaders. Report of the Committee appointed by the President of the Board of Education to consider the supply, recruitment and training of teachers and youth leaders, London: HMSO. [Part 2 is reproduced in the informal education archives, www.infed.org/archives/e-texts/mcnair_part_two.htm. Retrieved October 23, 2012].

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1972|1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First published in French as Esquisse d’une théorie de la pratique, précédé de trois études d’ethnologie kabyle, (1972).

BUPL (Børne- og Ungdomspædagogernes Landsforbund) – The Danish National Federation of Early Childhood Teachers and Youth Educators (undated). The work of the pedagogue: roles and tasks. Copenhagen: BUPL. [http://www.bupl.dk/iwfile/BALG-7X4GBX/$file/The%20work%20of%20the%20pedagogue.pdf. Retrieved: October 16, 2012].

Brühlmeier, A. (2010). Head, Heart and Hand. Education in the spirit of Pestalozzi. Cambridge: Sophia Books.

Bruner, J. (1996). The Culture of Education. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Cameron, C. (2004). ‘Social Pedagogy and Care: Danish and German practice in young people’s residential care’, Journal of Social Work. Vol. 4, no 2, pp. 133 – 151.

Cameron, C. and Moss, P. (eds.). (2011). Social Pedagogy and Working with Children and Young People: Where Care and Education Meet. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research. Lewes: Falmer.

Castle , E. B. (1961). Ancient Education and Today. Harmondsworth: Pelican.

Christian, C. and Green, M. (1998). Accompanying Young People on Their Spiritual Quest. London: The National Society/Church House Publishing.

Cohen, B. (2008). ‘Introducing “The Scottish Pedagogue”‘ in Children in Scotland Working it out: Developing the children’s sector workforce. Edinburgh: Children in Scotland.

Collander-Brown, D. (2005). ‘Being with another as a professional practitioner: uncovering the nature of working with individuals’ Youth and Policy (86) pp. 33-48.

Comenius, J. A. (1907). The Great Didactic, translated by M. W. Keatinge. London: Adam & Charles Black. [http://archive.org/details/cu31924031053709. Accessed October 4, 2012]

Dewey, J. (1963). Experience and Education, New York: Collier Books. [First published in 1938].

Dewey, J. (1966). Democracy and Education. An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: Macmillan. First published 1916.

Doyle, M. E. and Smith, M. K. (1999). Born and Bred? Leadership, heart of informal education. London: The Rank Foundation. [http://www.rankyouthwork.org/bornandbred/index.htm. Retrieved October16, 2012].

Doyle, M. E. and Smith, M. K. (2002). ‘Friendship and informal education’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [http://www.infed.org/biblio/friendship_and_education.htm. Retrieved October 23, 2012].

Eisner, E. W. (1979, 1985, 1994). The educational imagination: on the design and evaluation of school programs. New York: Macmillan.

Eisner, E. W. (2002). ‘What can education learn from the arts about the practice of education?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [www.infed.org/biblio/eisner_arts_and_the_practice_or_education.htm. Retrieved October 23, 2012].

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Green, M., & Christian, C. (1998). Accompanying young people on their spiritual quest. London: National Society/Church House Publishing.

Grundy, S. (1987). Curriculum. Product or praxis. Lewes: Falmer.

Gundem, B. B. (1998). Understanding European didactics – an overview: Didactics (Didaktik, Didaktik(k), Didactique). Oslo: University of Oslo. Institute for Educational Research. It is also reprinted in B. Moon, S. Brown and M Ben-Peretz (eds.) (2000) Routledge International Companion to Education. London: Routledge. Pp. 235-262.

Gundem, B. B. (December 07, 1992). Vivat Comenius: A Commemorative Essay on Johann Amos Comenius, 1592-1670. Journal of Curriculum and Supervision, 8, 1, 43-55.

Hamilton, D. (1999). ‘The pedagogic paradox (or why no didactics in England?)’, Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 7:1, 135-152.

Hamilton, D. & Gudmundsdottir, S. (1994). ‘Didaktik and/or curriculum’, Curriculum Studies, 2, pp. 345–350.

Hamilton, M. (2006). Just do it: Literacies, everyday learning and the irrelevance of pedagogy in Studies in the Education of Adults Vol. 38, No.2, Autumn pp.125-140.

Herbart, J. F (1892). The Science of Education: its general principles deduced from its aim and the aesthetic revelation of the world, translated by H. M. & E. Felkin. London: Swann Sonnenschein.

Herbart, J. F., Felkin, H. M., & Felkin, E. (1908). Letter and lectures on education: By Johann Friedrich Herbart ; Translated from the German, and edited with an introduction by Henry M. and Emmie Felkin and a preface by Oscar Browning. London: Sonnenschein.

Hilgenheger, N. (1993). ‘Johann Friedrich Herbart’, Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education. Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXIII, no. 3/4, 1993, p. 649-664. [http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/archive/publications/ThinkersPdf/herbarte.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2012].

Jeffs, T. and Smith, M. K. (2005). Informal Education. Conversation, democracy and learning, Ticknall: Education Now.

Kansanen, P. and Meri, M. (1999). ‘The didactic relation in the teaching-studying-learning process’ in B. Hudson et. al. (eds.) Didaktik/Fachdidaktik as Science(s) of the Teaching Professions. Umea?: Thematic Network on Teacher Education in Europe.

Kant, I. (1900). Kant on education (Ueber pa?dagogik). Translated by A. Churton. Boston: D.C. Heath. [http://files.libertyfund.org/files/356/0235_Bk.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012].

Kelly, A. V. (2009). The Curriculum: Theory and Practice 6e. London: Sage.

Kyriacou, C. (2009). ‘The five dimensions of social pedagogy within schools’, Pastoral Care in Education: An International Journal of Personal, Social and Emotional Development Volume 27, Issue 2. [http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02643940902897681?journalCode=rped20. Retrieved June 23, 2011].

Kornbeck, J. And Jensen, N. (eds.) (2009). The diversity of social pedagogy in Europe. Bremen: Europäischer: Hochschulverlag.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow. London: Allen Lane.

Kennell, N. M. (1995). The gymnasium of virtue: Education & culture in ancient Sparta. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Kornbeck, J. And Jensen, N. (eds.) (2011). Social Pedagogy for the Entire Lifespan: Volume I. Bremen: Europäischer: Hochschulverlag.

Künzli, R. (1994). Didaktik: Modelle der Darstellung. des Umgangs und der Erfahrung. Zurich: Zurich University, Didaktikum Aarau.

Lindeman, E. C. (1926). The Meaning of Adult Education. New York: New Republic, republished in 1989 by Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education. [Online version from: http://archive.org/details/meaningofadulted00lind. Retrieved October 23, 2012].

Lindeman, E. C. (1951). ‘Building a social philosophy of adult education’ in S. Brookfield (ed.) (1987) Learning Democracy: Eduard Lindeman on adult education and social change. Beckenham: Croom Helm.

Longenecker, R. N. (1982). ‘The Pedagogical Nature of the Law in Galatians 3:19-4:7’, Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 25.

Lorenz, W. (1994). Social Work in a Changing Europe. London: Routledge.

Miller, R. (2005). Holistic Education: A Response to the Crisis of Our Time. Paper was presented at the Institute for Values Education in Istanbul, Turkey in November, 2005. [http://www.pathsoflearning.net/articles_Holistic_Ed_Response.php. Retrieved: March 7, 2012].

Mills, C. W.(1959) The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press. The appendix ‘On intellectual craftsmanship’ can be read here.

Murphy, P. (1996). ‘Defining pedagogy’, in P. Murphy & C. Gipps (eds.) Equity in the Classroom: towards effective pedagogy for boys and girls. London: Falmer Press. [Also reprinted in Hall, K., Murphy, P., & Soler, J. (2008). Pedagogy and practice: Culture and identities. London: Sage. It can be downloaded from: http://www.corwin.com/upm-data/32079_Murphy%28OU_Reader_2%29_Rev_Final_Proof.pdf. Retrieved: February 12, 2012].

Noddings, Nel (2002). Starting at Home. Caring and social policy, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Noddings, N. (2005). ‘Caring in education’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, [www.infed.org/biblio/noddings_caring_in_education.htm. Retrieved October 16, 2012]

Ofsted (2011). Lesson observation – key indicators. London: Ofsted. [https://www.ncetm.org.uk/public/files/725865/Ofsted+key+indicators.pdf. Retrieved October 10, 2012].

Ofsted (2012). The framework for school inspection from September 2012. London: Ofsted. [http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/resources/framework-for-school-inspection-september-2012-0. Retrieved October 10,2012].

Pestalozzi, J. H. (2010). Leonard and Gertrude (from the 1885 edition published by D. C. Heath). Memphis: General Books.

Plato (1925). Lysis 208 C, trans. W. R. M. Lamb, Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rogers, C. (1967). ‘The interpersonal relationship in the facilitation of learning’ reprinted in Howard Kirschenbaum and Valerie Land Henderson (eds.) (1990) The Carl Rogers Reader. London: Constable, pages 304-311.

Sachs, J. (2001). Aristotle: Ethics, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (https://www.iep.utm.edu/aris-eth/. Retrieved: July 19, 2020).

Schön, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner. How professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith.

Simon, B. (1981). ‘Why no pedagogy in England?’ in B. Simon and W. Taylor (eds.) Issues for the 80’s. London: Batsford. Also reprinted in J. Leach and B. Cole (eds.) (1999). Learners and Pedagogy. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Smith, H., & Smith, M. (2008). The art of helping others: Being around, being there, being wise. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Smith, M. J. (2006). ‘The Role of the Pedagogue in Galatians’, Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 115. Liberty University. [http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/115. Retrieved January 23, 2012].

Smith, M. K. (1994). Local Education. Community, conversation, action, Buckingham: Open University Press.

Smith, M. K. (1999, 2007, 2009). ‘Social pedagogy’ in The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, [http://www.infed.org/biblio/b-socped.htm. Retrieved October 16, 2012].

Smith, M. K. (2016, 2019) Animate, care, educate. The core processes of social pedagogy, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/animate-care-educate-the-core-processes-of-social-pedagogy/. [ Retrieved: August 28, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2019). Haltung, pedagogy and informal education, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/haltung-pedagogy-and-informal-education/. Retrieved: August 28, 2019].

Washington, B. T. (1963). Up from slavery: An autobiography. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday.

Young, K. (1999). The Art of Youth Work. Lyme Regis: Russell House.

Young, N. H. (1987). ‘Paidagogos: The Social Setting of a Pauline Metaphor’, Novum Testamentum 29: 150.

Acknowledgements: The picture is by Luke Ellis-Craven and was sourced from Unsplash.

This piece includes material from another piece on infed.org: Smith, M. K. (2012, 2021). ‘What is education?’ in The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [www.infed.org/mobi/what-is-education/].

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2012, 2021). ‘What is pedagogy?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-pedagogy/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K. Smith 2012, 2015, 2019, 2021