Animate, care, educate – the core processes of pedagogy. Pedagogy can be viewed as a process of accompanying people and bringing flourishing and relationship to life (animation); caring for, and about, people (caring); and drawing out learning (education). Here Mark K Smith explores these core processes.

contents: introducing pedagogy • accompanying • core processes • animating • caring • educating • in conclusion • references • acknowledgements • how to cite this piece

Introducing pedagogy and social pedagogy

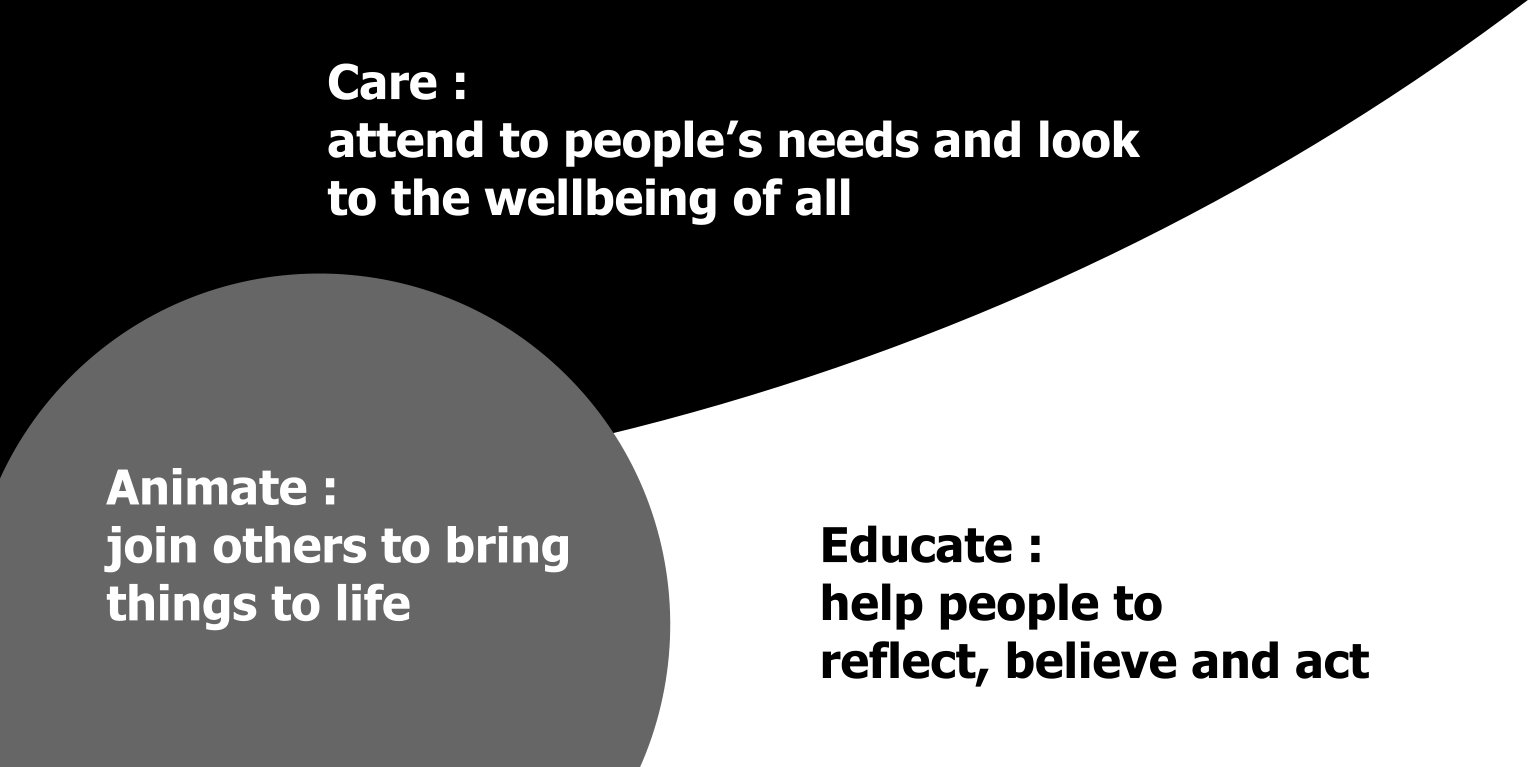

Pedagogy can be seen as a process of accompanying people and:

- working to bring flourishing and relationship to life (animation)

- caring for, and about, people (caring); and

- drawing out learning (education).

There has been a growing interest in pedagogy and social pedagogy in the UK and North America. Social pedagogy is often used to describe work straddling social work, social care and education. It embraces, for example, the activities of youth workers, residential and daycare workers (with children or adults), informal and specialist educators within schools, community educators and workers, and play and occupational therapists.

More holistic and group-oriented than dominant forms of social work and schooling, social pedagogy (sozial pädagogik) has its roots in German progressive education, and in action to tackle social problems in Britain and the United States. The development of work with young people, and the emergence of university and social settlements, are classic nineteenth-century examples of this. It also draws on the work of educational thinkers and philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, John Dewey and Maria Montessori (Eriksson, and Markström 2003).

These traditions of practice have led to ways of working that focus on flourishing, relationships and the integrity of pedagogues. Along with this has been an emphasis upon pedagogues taking their place alongside people, and accompanying them on their journeys.

Social pedagogy locates these processes in awareness of the social nature of living. It looks to the experiences and relationships of the everyday. This entails exploring people’s lifeworld (Lebenswelt). Here, following Jürgen Habermas (1987), we use ‘lifeworld‘ to describe the taken-for-granted practices, roles, social meanings that allow for shared understanding and interaction. Crucially, social pedagogy also makes sociality – connection, community and mutual aid – a core aim. (For more on social pedagogy see Social pedagogy: the development of theory and practice).

Accompanying

The original pedagogues in ancient Greece walked alongside their charges, sat with them in classrooms, and joined in with their activities. In many ways what they were doing connects directly with the experiences of many care workers, youth workers, support workers, social pedagogues and informal educators today. They spend a lot of time being part of other people’s lives – sometimes literally walking with them to some appointment or event or sitting with them in meetings and sessions. They can, also, be a significant person for someone over a long period of time – going through difficulties and achievements with them. Green and Christian (1998: 21) have described this as accompanying.

The greatest gift that we can give is to ‘be alongside’ another person. It is in times of crisis or achievement or when we have to manage long-term difficulties that we appreciate the depth and quality of having another person to accompany us… It is our opinion that the availability of this sort of quality companionship and support is vital for people to establish and maintain their physical, mental and spiritual health and creativity.

It is easy to overlook the sophistication of this relationship and the capacities needed to be ‘alongside another’. It entails ‘being with’ – and this involves attending to the other. Pedagogues have to be around for people; in places where they are directly available to help, talk and listen. They also have to be there for people: ready to respond to the emergencies of life – little and large (Smith and Smith 2008:18).

Core processes

We can see animation, caring and educating at work in different roles. As a practitioner there may be times when we seek to animate situations; to encourage participation or stimulate action. At others, we may focus on drawing out learning: helping people to attend to experiences and feelings, reflect, and develop understandings that allow them to act in more informed and committed ways. There will also be times when we assist people with the practical tasks of living because, for some reason, they are unable to do things themselves, or we should take care of them. Often all three elements are present in situations.

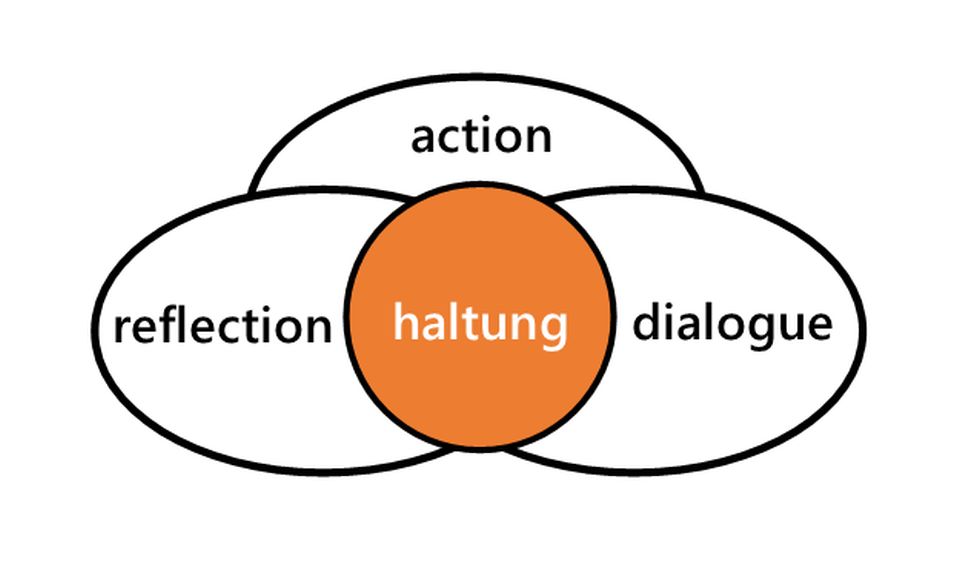

These three processes are, in turn, informed and guided by the mindset of the practitioner.

Within social pedagogy, this bundle of commitments and orientations is known by the German word ‘Haltung’. Social pedagogues look to situations, and the experiences of those involved, and then try to work out with people what the best course of action might be. They guide their actions by reference to their Haltung (Eichsteller 2010) rather than to a predefined curriculum or programme. Haltung is central to what they do. (You can read more about this in haltung, pedagogy and informal education).

Animating

Animation is often thought of as ‘making things move or happen’ – much as animators do of cartoon pictures. As pedagogues and educators, we can think of it as the process of stirring others into action, of helping them to find the motivation to change something in themselves, their relationships and in the world generally. This is the realm of the French tradition of animateurs (animatore in Italy), practitioners who lead and encourage participation in activities – especially in a cultural or artistic activity (see Smith 1999, 2009).

Go deeper, and we find practitioners working with others to engage with, and explore, the process of bringing things to life. Rather than just participating in an activity, the focus turns to the process of joining with others to organize. We move from encouraging someone to run with an interest or enthusiasm, for example, into bringing people together so that can they engage with an issue. This takes animation into the arena of community development and community organization.

Deeper still, animation involves facilitating a search for meaning in life and, indeed, a zest for life. This is a central concern for educators and pedagogues working within religious organizations and, more generally, for those facilitating well-being and mindfulness programmes. In the case of the latter it entails practitioners encouraging people to engage in practices that enable them to be:

… fully awake to the myriad different experiences that are going on around and within us all the time; delighting in things we had never noticed before – the subtle colours, aromas and textures of all we encounter; even waking up fully to the thought processes that are constantly going on in our minds. (Stead 2016: 19).

At all three levels, the process involves, as Larry Parsons (2002) has said, looking for a ‘spark’, nurturing it, and then fanning it into flame. Practitioners nurture possibility and hope, and open doors into different ways of doing and seeing things. But how do they do this? They look to two principles. First, and to rework Tim Stead’s work, you can teach about animation:

… and your hearers (if they don’t get bored) will acquire an intellectual knowledge that is almost entirely useless to them – because what they really need is to experience [it] for themselves (2016: 20).

Second, practitioners need to foster an atmosphere of ‘openness and non-judging compassion’ (op. cit.). And compassion, according to Karen Armstrong (2011: 11) means enduring something with another person and entering ‘generously into her point of view’. [To be fair to Karen Armstrong she also talks about standing in the other person’s shoes and feeling their pain as they do – but I am omitting that here largely because I do not believe that is possible, nor necessarily helpful as the scale of the pain involved could impair our ability as pedagogues to respond appropriately – see Smith 1994: 33-6]. The language of caring seems more useful.

Caring

As practitioners, we are concerned about people’s needs and well-being and giving direct help with the practical and emotional tasks involved in daily life. In other words, caring is an essential element of our practice.

Care and caring are words that appear straightforward, but after a few moments thought can dissolve into something complex. In social work ‘care’ is often linked to being looked-after. The two obvious examples here are children in care, and the care of older and frailer people both in their own homes and in care homes and day centres. If we take the latter we can quickly see this care is both practical – help with washing, toileting, getting dressed, shopping and cooking – and social and emotional. It can provide a space for people to talk about their worries and much needed everyday contact with others.

Caring goes well beyond being ‘looked-after’ however. A helpful way of thinking about this has been provided by Nel Noddings (2013). She distinguishes between ‘caring about’ and ‘caring for’.

‘Caring-for’ someone involves sympathy – what Nel Noddings describes as ‘feeling with’. We must be open to what the other person is saying and might be experiencing and reflecting upon it. Crucially, when caring for another we are concerned with their interests. Carers respond to the cared-for in ways that are, hopefully, helpful.

For this to be called ‘caring’ a further step is needed. There must also be some understanding on the part of those being cared-for that an act of caring has happened. Caring involves a relationship between the carer and the cared-for, and a degree of reciprocity. Both gains from the relationship in different ways and both give (Smith 2004).

‘Caring about’ ‘expresses some concern but does not guarantee a response to one who needs care’ (2013:14). Caring-about is something more general – and takes us more into the public realm. We learn first what it means to be cared-for. ‘Then, gradually, we learn both to care for and, by extension, to care about others’ (Noddings 2002: 22). This caring-about, Noddings argues, is almost certainly the foundation for our sense of justice.

Educating

Practitioners facilitate or encourage learning about things that matter. Classically we do this by encouraging people to return to past experiences, reflect and to try out new ways of handling situations. A major part of that task is working with people to explore just what matters.

Education is taken here to mean a process of inviting truth and possibility, of encouraging and giving time to discovery. The task is to educe (related to the Greek notion of educere), to bring out or develop potential. It is a process that is:

- Deliberate and hopeful. It is learning we set out to make happen in the belief that people can ‘be more’;

- Informed, respectful and wise. A process of inviting truth and possibility.

- Grounded in a desire that at all may flourish and share in life. It is a cooperative and inclusive activity that looks to help people to live their lives as well as they can.

In short, it can be defined as ‘the wise, hopeful and respectful cultivation of learning undertaken in the belief that all should have the chance to share in life’ (Smith 2015). [For more on the nature of education see What is education? A definition and discussion]

In conclusion

Social pedagogues and informal educators work in very different settings and have a range of titles – community sports worker, support worker, outdoor educators, youth worker, social pedagogue, specialist educator, youth pastor, community development worker, residential worker – the list goes on.

What most of us share is that we try to offer opportunities and experiences that help people to grow, relate to one another and live happier and more fulfilling lives. We try to build relationships where children, young people and adults:

- Learn more about themselves, others and the world we share.

- Talk about things that matter to them, are heard, and helped.

- Act to improve their lives, relationships and communities.

To do this we have to animate, care and educate (ACE).

References

Armstrong, K. (2011). Twelve steps to a compassionate life. London: The Bodley Head.

Christian, C. and Green, M. (1998). Accompanying Young People on Their Spiritual Quest. London: The National Society/Church House Publishing.

Eriksson, L. and Markström, A-M (2003). ‘Interpreting the concept of social pedagogy’ in Anders Gustavsson, Hans-Erik Hermansson and Juha Hämäläinen (eds.). Perspective and theories in social pedagogy. Göteborg: Daidalos.

Green, M. and Christian, C. (1998). Accompanying Young People on Their Spiritual Quest. London: The National Society/Church House Publishing.

Gustavsson, A., Hermansson, H.-E., & Hamalainen, J. (eds.) (2003). Perspectives and theory in social pedagogy. Go?teborg: Daidalos.

Habermas, J. (1987). The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. II: Lifeworld and System. T. McCarthy (trans.). Boston: Beacon.

Kant, I. (1900). Kant on Education (Ueber paedagogik). Translated by A. Churton. Boston: D.C. Heath. [http://files.libertyfund.org/files/356/0235_Bk.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012].

Noddings, N. (2002). Starting at Home. Caring and social policy. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Noddings, N. (2005). ‘Caring in education’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [ https://infed.org/dir/caring-in-education/. Retrieved: May 27, 2019].

Noddings, N. (2013). Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. 2e. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Parsons, L. (2002). Youth work and the spark of the divine. London: Rank Foundation/YMCA George Williams College. [http://www.infed.org/christianyouthwork/spark_of_the_divine.htm. Retrieved; May 27, 2019]

Smith, H., & Smith, M. (2008). The art of helping others: Being around, being there, being wise. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Smith, M. J. (2006). ‘The Role of the Pedagogue in Galatians’, Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 115. Liberty University. [http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/115. Retrieved January 23, 2012].

Smith, M. K. (1994). Local Education. Community, conversation, praxis. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Smith, M. K. (1999, 2009) ‘Animateurs, animation and fostering learning and change’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [www.infed.org/mobi/animateurs-animation-learning-and-change. Retrieved May 27, 2019]

Smith, M. K. (2012). ‘What is pedagogy?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/what-is-pedagogy/. Retrieved: March 16, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2015). What is education? A definition and discussion. The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/what-is-education-a-definition-and-discussion/. Retrieved: May 27, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2019). Haltung, pedagogy and informal education, Developing Learning. [https://infed.org/dir/haltung-pedagogy-and-informal-education/]

Stead, T. (2016). Mindfulness and Christian Spirituality. Making space for God. London: SPCK.

Young, N. H. (1987). ‘Paidagogos: The Social Setting of a Pauline Metaphor’, Novum Testamentum 29: 150.

Acknowledgements: Photo by Tegan Mierle on Unsplash

This piece uses some material from Smith, M. K. (2012). ‘What is pedagogy?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/what-is-pedagogy/].

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2016, 2019, 2025) Animate, care, educate. The core processes of pedagogy, infed.org [https://infed.org/dir/animate-care-educate-the-core-processes-of-social-pedagogy/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K Smith 2016, 2019, 2025.

updated: January 3, 2026