Mark K Smith explores how, in the context of the ‘new normal’, educators, pedagogues and practitioners need to work to create the conditions for education, learning and change. This article is part of a series: dealing with the new normal • offering sanctuary • offering community • offering hope]

contents: introduction • dealing with the new normal • children and young people • offering sanctuary • offering community • offering hope • our approach • conclusion – how do schools and organizations change? • further reading and references • acknowledgements • how to cite this piece

Creating places of sanctuary, community, and hope for children and young people.

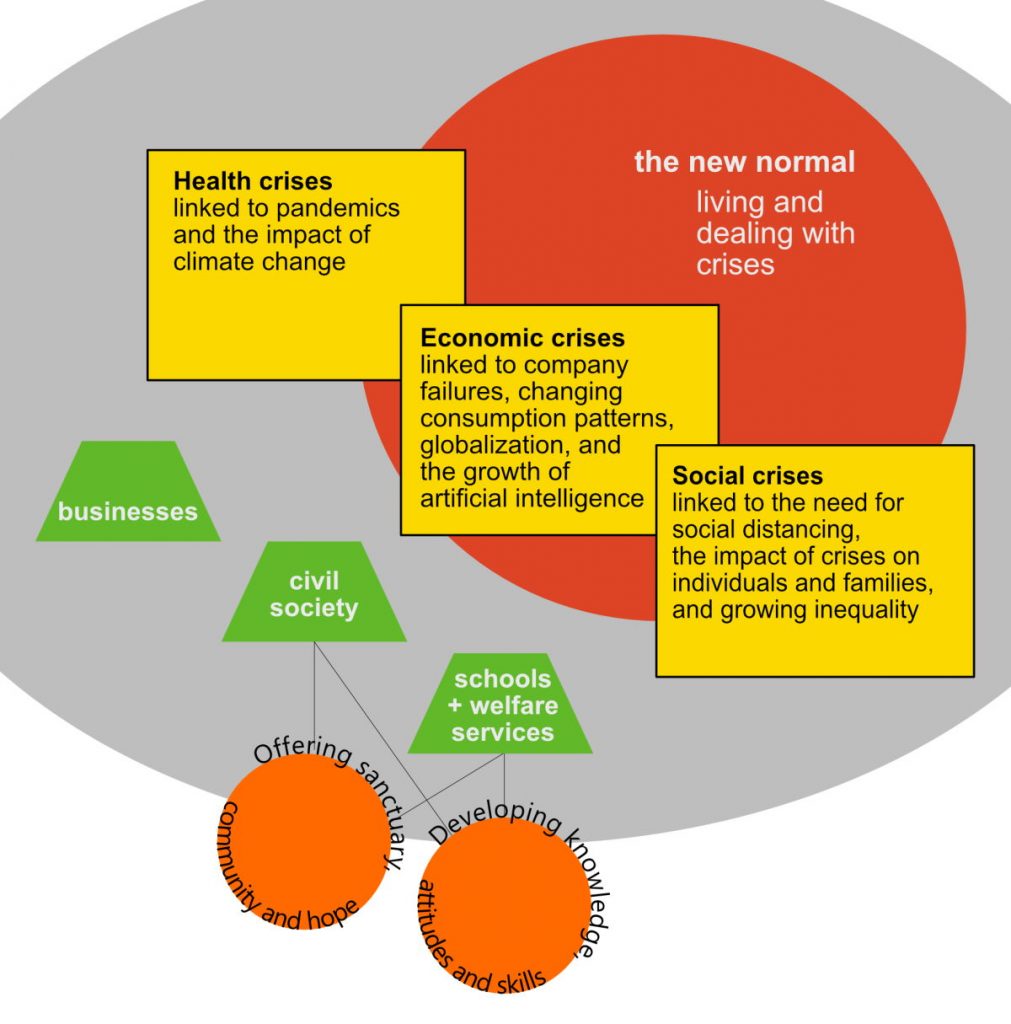

The emergence of COVID-19 – and the pandemic that followed – changed the lives of many millions of people. It also brought home the scale of crises we already knew about but have often chosen to ignore. Climate and ecological change, deepening inequality and transformations in the way economies work have both helped to create the conditions for the pandemic and are part of the ‘new normal’ that we must address as educators, pedagogues and practitioners.

In this piece, I want to set out what is involved in working with children and young people so that they have space to begin to explore these fundamental issues, to contain their worries, and develop their capacity to create change. Schools, colleges and many civil society organizations will have to alter the way in which they work and the focus for their activities. Here we examine three, crucial, areas for intervention – offering sanctuary, community and hope.

Dealing with the ‘new normal’

The COVID-19 ‘pandemic is a health crisis, social crisis, and economic crisis of unprecedented and permanent implications for our society’ (Scottish Government 2020). When added to existing currents of change, the ‘permanent implications’ are going to be profound. There is a deep need to ‘advance equality and protect human rights in everything we do’ (op. cit.).

The ‘new normal’ goes well beyond keeping two metres away from others in shops and on the street. It entails living and dealing with the underlying forces creating the crises, such as climate and ecological change. We are faced with existential risk. Arguably, safeguarding humanity’s future has become the challenge of our time (Ord 2020: 14). ‘The ultimate purpose is to allow our descendants to fulfil our potential, realising one of the best possible futures open to us’ (op. cit.: 33).

This has far-reaching consequences for state services, civil society and business. On the one hand, there appears to have been a significant rise in local civil action to support health and welfare activity. On the other, we have seen a major focus on, and extension of, surveillance activity such as the COVID-19 tracking apps (and associated changes in mobile operating systems by Apple and Google/Android). To this must also be added an emphasis on remote activity, whether it be working, leisure activities and shopping. As Naomi Klein (2020) has put it:

Something resembling a coherent pandemic shock doctrine is beginning to emerge. Call it the Screen New Deal. Far more hi-tech than anything we have seen during previous disasters, the future that is being rushed into being as the bodies still pile up treats our past weeks of physical isolation not as a painful necessity to save lives, but as a living laboratory for a permanent – and highly profitable – no-touch future.

There are special implications in all this for children and young people – and schooling. Talk of ‘reimagining education’ and of ‘working smarter’ has spread. The New York state governor, Andrew Cuomo is a classic example of this:

“So, it’s not about just reopening schools,” Cuomo said at his daily coronavirus briefing. “When we are reopening schools, let’s open a better school, and let’s open a smarter education system. … Bill Gates is a visionary in many ways, and his ideas and thoughts on technology and education he’s spoken about for years, but I think we now have a moment in history where we can actually incorporate and advance those ideas.” (Blad 2020)

The concern is to develop more remote ways of working with children and young people – and to reduce the cost of teaching and physical plant. The beneficiaries of this are dominant technology companies such as Amazon, Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook; companies that are part of the existential threat we face. Schools and civil society organizations need to change. There is a place for more individualized and self-directed learning – but this can only take place in the context of in-person encounter and group activity if children and young people are to grow and flourish. Being physically present – unmediated by servers and screens – is fundamental to our development and flourishing (see, for example, Turkle 2017). Reduced face-to-face contact among young people and their friends during the pandemic could have damaging long-term consequences according to some neuroscientists (Orbin et. al. 2020).

This piece argues that children and young people need sanctuary, community and hope – and that schools must develop as places where these can be experienced directly – person to person. There are other fundamental changes needed in the content and direction of the curriculum in schools and colleges, which we will not deal with here.

infed

Children and young people

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic many children and young people did not have high hopes about their future and were not that satisfied with their current experience (WHO 2016; UNICEF 2016). Climate change had become both a focus for political action by some children and young people – and there were ‘worrying levels of environment-related stress and anxiety’ among young people and children (Taylor and Murray 2020). Economically, as a group in the UK, it looked like they would be poorer at every stage of their life than their parents (O’Connor 2018; Bialek and Fry 2019). Younger generations were also having to pay significantly more to support the pensions and healthcare of those approaching, or already in, older age. John Lancaster (2019) explains:

When the retired generation is bigger than the working generation, there are obvious problems with making the sums work. You end up with different versions of the welfare state being experienced by different generations. A huge body of social science has been done on this subject, and you can sum it up in seven words: the baby boomers ate all the pies.

This combined with college loan debt, rising home prices (whether renting or buying) and more limited work opportunities mean growing financial inequality between generations.

Many also faced a further problem – widening inequality between rich and poor. Children and young people in less well-off families have been disproportionately affected by both austerity policies since the banking crisis of 2007-8 and the growing gap in income and wealth before that. The Resolution Foundation (Clarke 2019) has described the 2008-11 group in the UK as the ‘crisis cohort’. Now Covid-19 is, according to Will Hutton (2020), creating a ‘super-crisis cohort’, ‘about to experience the same effect, only worse. Unless government, business and society collectively act, what lies ahead will be unfairness heaped upon unfairness’.

Some children and young people feel that they have nothing to live for. Around one in ten children and young people aged 5-16 suffer from a diagnosable mental health disorder (Hagell 2012). Increasing numbers of children and young people suffer from severe depression. Child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) operating under reduced budgets have been unable to respond and increasing numbers are being turned away.

The ‘new normal’ involves us all, both because there is a huge clearing up job and the need to address the far-reaching and continuing health, economic and social crises creating a ‘super-crisis cohort’ of children and younger people. Schools, religious groups and community organizations must respond to this post-COVID-19 situation.

sweet peas, spring 2020 | infed

Offering sanctuary

Churches, schools and community groups have often looked to provide safe, friendly places where children, young people and adults can be with their peers; can broaden horizons and learn; and even organize things for themselves. Many have sought to create sanctuaries – spaces away from the pressures of daily life where children and young people are able to breathe and be themselves (see, for example, McLaughlin, Irby and Langman 1994). A lot of the stories we may hear about significant moments in people’s lives involve experiencing such ‘space’ – being in a place and having time to give room to experience and feelings.

In recent times sanctuary is often used to describe a place of safety and of refuge – a space from. Its older meaning denotes a shrine or sacred place. A sanctuary garden, for example, is a place for retreat in which we can be rejuvenated emotionally and spiritually. It is a place where inner harmony may be reclaimed (Curl and Wilson 2015) – a space for.

Most children and young people do not experience great problems whilst growing up: their relationships with their parents or carers are relatively harmonious and caring, and the transitions that they make are accomplished without vast storm and stress. Yet while some flourish, most just get by. A small but significant group, however, experience serious personal troubles. A growing number suffer a diagnosable mental disorder. All require sanctuary in some form, but a sizeable group require specialist provision in institutions like schools to get away from daily pressures and have time for themselves. They need to be in settings where they are not subjected to constant demands and where they can escape, or at least contain, stress and anxiety. They may want special spaces – times and places – that allow them to feel safe and connected.

To explore sanctuary – to appreciate what it is – we should look at what children and young people need space from, and what they need space for. These questions link to something like the distinction popularized by Isaiah Berlin (1958) between negative liberty – which he initially defined as freedom from – and positive liberty or freedom to. The former involves a relative absence of constraints imposed by others; the latter the ability and opportunity to achieve their goals (as defined by themselves) for themselves. Most need space reasonably clear of interference and compulsion if they are to think and act for themselves (one reason why schools can fail as educational environments). In a similar way, the ability to think critically helps us to recognize why certain forms of freedom are necessary. ‘Space for’ and ‘space from’ are related.

Pedagogues, workers, and educators have traditionally been troubled by the negative elements of local cultures, family life, schooling, and work-life. The situation has been exacerbated in recent years by several further factors but here note two: the sheer level of routine surveillance that children and young people experience in many countries; and impact of materialism and secularization. Taken together these can depress the spirit, stunt development, and get in the way of children and young people being at home with themselves and others.

[For a full discussion of what is involved in offering sanctuary go to Offering sanctuary to children and young people in schools and local organizations.]

Offering community

Alongside sanctuary, one of the striking things about work with children, young people, and adults in the first half of the twentieth century is the number of times we stumble across the idea of ‘fellowship’. The word has remained a part of the vocabulary of many practitioners but has also been joined, or replaced, by ‘community’. In religious and local groups, and institutions like homes and schools, we often find concern that many feel alienated and that they do not belong. Not surprisingly, those within these settings look to work with them to cultivate relationship and a sense of ‘community’.

Many are also focused on offering a sense of belonging and the chance to build networks to use and contribute to. But the work we do moves well beyond this. It also involves creating environments in which friendship can flourish, social capital is developed, and associational life and social change encouraged (see Gilchrist 2019).

‘Community‘ can be used as a way of describing: a place; groupings of people who share a common characteristic other than place; and a sense of belonging (Smith 2013). All three meanings are part of the experience of religious and community groups. They are based in place, share certain beliefs or practices and look to koinonia or fellowship). Pedagogues, educators and workers with children and young people offer the chance to join others, to be a part of something. We ask people to participate, to share in activity and to make some sort of commitment to each other. At a basic level, this involves sharing interests and working toward some goal.

When we ‘offer community’ we are inviting people to develop an attachment to a group and that involves:

- Building a group identity and clear boundaries. People need to know what they are belonging to, and what the limits are.

- Joining networks of relationships that offer provide support, information and access to opportunities.

- Developing shared norms and habits such as tolerance, reciprocity and trust. (Smith 2013)

Through this, we create a context for the development of friendship, social capital and the bedrock of civil society – associational life. To offer community, we create the space and support to do these things and to open the opportunity to participate in social change.

For a full discussion of what is involved in offering community go to: Offering community to children and young people in schools and local organizations]

Offering hope

Sanctuary allows people space, community a sense of belonging and networks to use and contribute to. Hope, the third of our themes, looks to creating environments where people can start to move forward and to sense that flourishing is possible.

Hope is something more than optimism. It is not simply looking on the bright side or believing that ‘everything was, is, or will be fine’ (Solnit 2016: 12). For a start, hope can be for things that we judge to be unachievable. Furthermore, ‘looking on the bright side’ can work against working to make things better. It both warps our view of reality and reduces the motivation to act. There is no need to change if things will change anyway.

John Macquarrie (1978) has given us a starting point for thinking about what hope might be. For him hope was:

An emotion. Hope, he says, ‘consists in an outgoing and trusting mood toward the environment’ (op. cit.: 11). We do not know what will happen but take a gamble. ‘It’s to bet on the future, on your desires, on the possibility that an open heart and uncertainty is better than gloom and safety. To hope is dangerous, and yet it is the opposite of fear, for to live is to risk’ (Solnit 2016: 21).

A choice or intention to act. Hope ‘promotes affirmative courses of action’ (Macquarrie 1978: 11). Hope alone will not transform the world. Action ‘undertaken in that kind of naïveté’, wrote Paulo Freire (1994: 8), ‘is an excellent route to hopelessness, pessimism, and fatalism’. Hope and action are linked. Rebecca Solnit (2016: 22) put it this way, ‘Hope calls for action; action is impossible without hope… To hope is to give yourself to the future, and that commitment to the future makes the present inhabitable’.

An intellectual activity. Hope is not just feeling or striving, according to McQuarrie it has a cognitive or intellectual aspect. ‘[I]t carries in itself a definite way of understanding both ourselves – and the environing processes within which human life has its setting’ (op. cit.).

This provides us with a starting point and language to help make sense of things; a ‘vocabulary of hope’ to imagine change for the better. Here we look at it is a process of us:

- learning from our experiences and conversations,

- thinking about what we would like to happen and steps we might need to take, and

- believing in the possibility of it happening.

These three elements connect with what John MacQuarrie was proposing but are not dependent on there being ‘ultimate ends’ and look to learning and cooperation – with each other and the world of which we are a part. There is an ‘us’ in hope as well as an ‘I’.

[For a full discussion of what is involved in offering hope go to What is hope? How can we offer it to children and young people in schools and local organizations?]

Our approach

The approach we advocate here is not goal-oriented in the way that many self-help books and state curricula are. You set a goal, then plan how to achieve it, and test to see whether it has been achieved. Instead, it flows from what we discussed earlier. As pedagogues, workers and educators we invite people to reflect, commit and act. It is a process that we can do for ourselves and encourage others to develop.

Alison Gopnik (2016) has provided a helpful way of understanding this orientation. It is that educators, pedagogues and practitioners need to be gardeners rather than carpenters. A key theme emerging from her research over the last 30 years, is that children learn by actively engaging their social and physical environments – not by passively absorbing information. They learn from other people, not because they are being taught – but because people are doing and talking about interesting things. The emphasis in a lot of the literature about parenting (and teaching) presents the roles much like that of a carpenter.

You should pay some attention to the kind of material you are working with, and it may have some influence on what you try to do. But essentially your job is to shape that material into a final product that will fit the scheme you had in mind to begin with.

Instead, Gopnik argues, the evidence points to being a gardener.

When we garden, on the other hand, we create a protected and nurturing space for plants to flourish. It takes hard labor and the sweat of our brows, with a lot of exhausted digging and wallowing in manure. And as any gardener knows, our specific plans are always thwarted. The poppy comes up neon orange instead of pale pink, the rose that was supposed to climb the fence stubbornly remains a foot from the ground, black spot and rust and aphids can never be defeated.

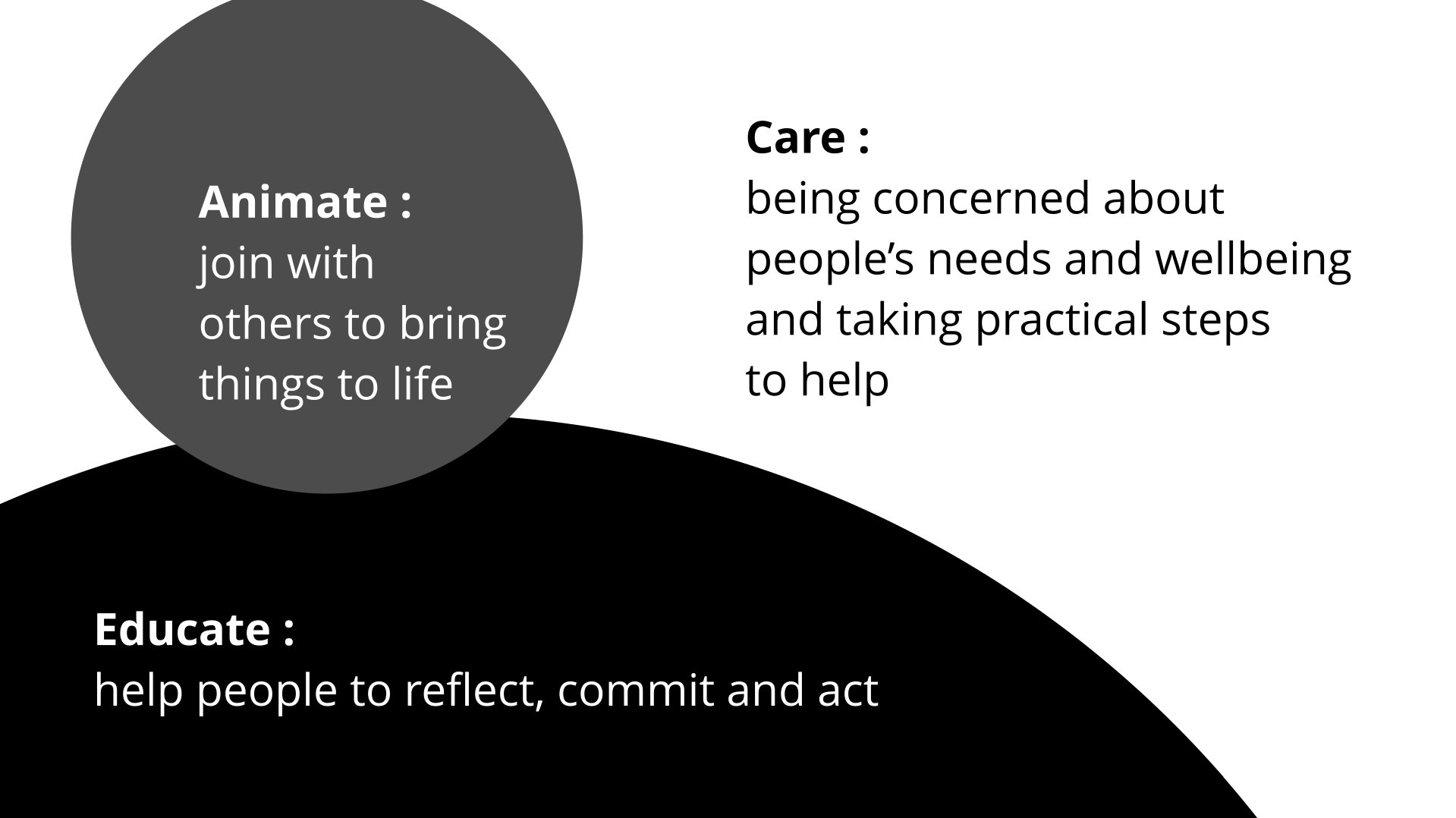

The image of gardening connects nicely with that of pedagogy, which can be viewed as a process of accompanying people, and:

- bringing flourishing and relationship to life (animation)

- caring for, and about, people (caring); and

- drawing out learning (education) (Smith 2012; 2019a).

We find this focus right from the start in the distinction made within ancient Greek society between the activities of pedagogues (paidagögus) and subject teachers (didáskalos). The latter, as Kant (1900: 23-4) put it, ‘train for school only, the other for life’. In short, pedagogues set out with the idea that all should share in life, and an appreciation of what people may need to flourish. In many ways we are also asking the same questions as Kant (1787) – What can I know? What ought I to do? What may I hope?

Conclusion – how do schools and organizations change?

What practical steps can schools and local organizations take to create places of sanctuary, community and hope? There are some basic things to bear in mind in the short run:

- Start small and avoid grand plans. This will involve a way of thinking and working based in organic growth (which might be quite quick) and diverse solutions.

- Look around at the spaces, activities and practices you have – and consider how they may be used or strengthened as places of sanctuary, community and hope.

- Release the inner pedagogue – this is not a didactic way of working and has to run alongside more traditional forms of teaching.

- Encourage the development of clubs and groups that are organized and managed by their members. In schools this means, in particular, attending to lunchtime and after school activity, and to the significance of music and art.

- Consider what specialist provision you might need for different groupings of children and young people.

Three more fundamental tasks for those working in schools are to:

- Let go of the idea that schools are fundamentally about teaching a curriculum. They are also places of pedagogy – of animation, care and education. There is a real sense in which we need to reinvent the school if it is to properly address the needs of children and young people.

- Value the work of specialist pedagogues, educators and care givers. A common characteristic of occupational groups is to look down on other occupational groups – and to think they know best. This is especially the case where one group (in this case teachers) is dominant in an institution.

- Work to convince funders (and in particular state funders) that resources are needed to employ a much wider range of practitioners.

The work and commitment of many of those involved in work with children, young people and communities is powerful. While the institutional environment within which they work is significant, it is the integrity, faith and critical engagement of practitioners that, in the end, carry the potential to foster flourishing. We need educators, pedagogues and workers who are disposed and able to journey in hope, join in community with others, and create with children and young people space for relationship, reflection and experience.

Further reading and references

The new normal series

Dealing with the ‘new normal’. Offering sanctuary, community and hope to children and young people in schools and local organizations. This provides an overview of the context, and an outline of the way forward for schools and local organizations.

Offering community to children and young people in schools and local organizations.

What is hope? How can we offer it to children and young people in schools and local organizations?

For those new to social pedagogy or to the way in which we are talking about pedagogy here there are a number of articles on infed that may be helpful.

The core processes of social pedagogy – animation, care and education – are discussed in a new article: Animate, care, educate – the core processes of social pedagogy.

Within informal education and social pedagogy, the character and integrity of practitioners are seen as central to the processes of working with others. The German notion of ‘haltung’ draws together key elements around this pivotal concern for pedagogues and informal educators. Explore this in another infed article: Haltung, pedagogy and informal education.

For an overview of developments in theory and practice: social pedagogy.

Many discussions of pedagogy make the mistake of seeing it as primarily being about teaching. Rather pedagogy needs to be explored through the thinking and practice of those educators who look to accompany learners; care for and about them; and bring learning into life. Teaching is just one aspect of their practice: What is pedagogy?

References

Barnett, L. (1962). Adventure with Youth: a handbook for church club leaders, London: Methodist Youth Department.

Beem, C. (1999) The Necessity of Politics. Reclaiming American public life, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Bell, S. and Coleman, S. (1999). ‘The anthropology of friendship: enduring themes and future possibilities’ in S. Bell and S. Coleman (eds.) The Anthropology of Friendship, London: Berg.

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A. and Tipton, S. M. (1996). Habits of the Heart. Individualism and commitment in American life 2e. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Berlin, I. (1958). Two Concepts of Freedom. Oxford: Clarendon Press

Bialik, K and Fry, R. (2019). Millennial life: How young adulthood today compares with prior generations, Pew Research Center. [https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/essay/millennial-life-how-young-adulthood-today-compares-with-prior-generations/. Retrieved February 28, 2019].

Blad, E. (2020). New York State Teams With Gates Foundation to ‘Reimagine Education’ Amid Pandemic, Education Week May 13. [https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/campaign-k-12/2020/05/new-york-gates-coronavirus-education.html. Retrieved May 13, 2020]

Brew, J. Macalister. (1957). Youth and Youth Groups, London: Faber & Faber.

Buber, M. (1958). I and Thou 2e, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark and (1947) Between Man and Man, London: Kegan Paul (new edition 2002 – London: Routledge).

Clarke, C. (2019). Growing Pains: the impact of leaving education during a recession on earnings and employment. London: The Resolution Foundation. [https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/growing-pains-the-impact-of-leaving-education-during-a-recession-on-earnings-and-employment/. Retrieved April 28, 2020].

Cowan, M. A. and Lee, B. J. (1997) Conversation, Risk and Conversion. The inner and public life of small Christian communities. New York: Orbis.

Curl, J. S. and Wilson, S. (2015). The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. 3e. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davies, W. (2005) Modernising with Purpose. A Manifesto for a Digital Britain, London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Denworth, L. (2020). Friendship. The evolution, biology and extraordinary power of life’s fundamental bond. London: Bloomsbury.

Doyle, M. E. and Smith, M. K. (1999). Born and Bred? Leadership, heart and informal education. London: YMCA George Williams College/Rank Foundation.

Edwards, M. (2014) Civil Society 3e. Cambridge: Polity.

Elsdon, K. with Reynolds, J. and Stewart, S. (1995) Voluntary Organizations. Citizenship, learning and change, Leicester: NIACE.

Field, J. (2017). Social Capital 3e. Abingdon: Routledge. [Page numbers refer to the Adobe epub version).

Freire, P. (1994) Pedagogy of Hope. Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. With notes by Ana Maria Araujo Freire. Translated by Robert R. Barr. New York: Continuum.

Gallagher, M. W. and Lopez, S. J. (eds.) (2018). The Oxford Handbook of Hope. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gilchrist, A. (2019). The Well-Connected Community: A networking approach to community development 3e. Bristol: Policy Press.

Gopnik, A. (2016). The Gardener and the Carpenter. What the new science of child development tells us about the relationship between parents and children. London: Random House.

Hagell, A. (ed.) (2012). Changing adolescence. Social trends and mental health. Bristol: Policy Press.

Halpin, D. (2003a). Hope and Education. The role of the utopian imagination. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Halpin, D. (2003b). Hope, utopianism and educational renewal, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/hope-utopianism-and-educational-renewal/. Retrieved June 22, 2019].

Hemmings, H. (2011). Together. How small groups achieve big things. London: John Murray.

Hirst, P. (1994). Associative Democracy. New forms of economic and social governance. Cambridge: Polity Press.

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching Community. A pedagogy of hope. New York: Routledge.

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee (2019). Impact of social media and screen-use on young people’s health. Fourteenth Report of Session 2017-19. [https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmsctech/822/822.pdf. Retrieved February 12, 2020].

Hutton, W. (2020). Young Britons have been hit hard. We owe them a future they can believe in, The Guardian April 19. [https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/19/young-britons-have-been-hit-hard-we-owe-them-a-future-they-can-believe-in. Retrieved April 19, 2020].

Illich, I. (1974). Tools for Conviviality. London: Fontana.

Jeffs, T. J. and Smith, M. K. (2020). Informal Education. Conversation, democracy and learning 4e.

Kant, I. (1787). The Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by J. M. D. Meiklejohn. Part 11. [http://www.fullbooks.com/The-Critique-of-Pure-Reason11.html. Retrieved April 28, 2020].

Kant, I. (1900). Kant on Education (Ueber paedagogik). Translated by A. Churton. Boston: D.C. Heath. [http://files.libertyfund.org/files/356/0235_Bk.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012].

Klein, N. (2000). No Logo. London: Flamingo.

Klein, Naomi. (2019). On Fire: The burning case for a green new deal. London: Allen Lane.

Klein, N. (2020). Screen New Deal. Under Cover of Mass Death, Andrew Cuomo Calls in the Billionaires to Build a High-Tech Dystopia, The Intercept. May 8. [https://theintercept.com/2020/05/08/andrew-cuomo-eric-schmidt-coronavirus-tech-shock-doctrine/. Retrieved: May 13, 2020].

Lancaster, J. (2019). Climate change is the deadliest legacy we will leave the young, The Guardian, February 6. [https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/feb/06/climate-change-deadliest-legacy-baby-boomers-young-people. Retrieved February 8, 2019].

Lane, R. E. (2000) The Loss of Happiness in Market Economies, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Layard, R. (2011). Happiness. Lessons from a new science 2e. London: Penguin.

Layard, R. with Ward, G. (2020). Can we be Happier? Evidence and ethics. London: Pelican Books.

Lear, J. (2006). Radical Hope. Ethics in the face of cultural devastation. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press.

McLaughlin, M. W., Irby, M. A., and Langman, J. (1994). Urban Sanctuaries. Neighbourhood organizations in the lives and futures of inner-city youth. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

MacQuarrie, J. (1978). Christian Hope. Oxford: Mowbray.

Moltmann, J. (1967). Theology of hope: On the ground and the implications of a Christian eschatology. New York: Harper & Row. Available on-line: http://www.pubtheo.com/page.asp?PID=1036.

Nouwen, H. (1975). Reaching Out. New York: Doubleday

O’Connor, S. (2018), Millennials poorer than previous generations, data show, Financial Times February 23. [https://www.ft.com/content/81343d9e-187b-11e8-9e9c-25c814761640. Retrieved April 10, 2019].

Orbin, A., Tomova, A., and Blakemore, S-J. (2020). The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health, The Lancet June 12. [https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanchi/article/PIIS2352-4642(20)30186-3/fulltext. Retrieved June 12, 2020].

Ord, T. (2020). The Precipice. Existential risk and the future of humanity. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Pahl, R. (2000). On Friendship. Cambridge: Polity.

Palmer, P. J. (1983, 1993). To Know as We are Known. Education as a spiritual journey. San Francisco: HarperSan Francisco.

Palmer, P. J. (2017). The Courage to Teach. Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. San Francisco: John Wiley. First published in 1998.

Pieper, J. (1997). Faith, Hope, Love. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone. The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Rogers, C. (1967) ‘The interpersonal relationship in the facilitation of learning’ reprinted in H. Kirschenbaum and V. L. Henderson (eds.) (1990) The Carl Rogers Reader, London: Constable.

Scottish Government (2020). COVID-19. A framework for decision making. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government. [https://www.gov.scot/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-framework-decision-making/. Retrieved April 23, 2020]

Smith, M. K. (2000, 2012) ‘Association, la vie associative and lifelong learning’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education [www.infed.org/mobi/association-la-vie-associative-and-lifelong-learning. Retrieved: June 16, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2001, 2002, 2013). ‘Community’ in The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/community/. Retrieved: April 25, 2020].

Smith, M. K. (2012). ‘What is pedagogy?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-pedagogy/. Retrieved: March 16, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2015). What is education? A definition and discussion. The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-education-a-definition-and-discussion/. Retrieved: May 27, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2016, 2018). ‘What is teaching?’ in The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-teaching/. Retrieved: May 31, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2019a). Animation, care and education – the core processes of social pedagogy, Developing Learning. [https://infed.org/mobi/animate-care-educate-the-core-processes-of-social-pedagogy/. Retrieved: May 28, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2019b). Haltung, pedagogy and informal education, infed.org. [https://infed.org/mobi/haltung-pedagogy-and-informal-education/. Retrieved: April 28, 2020].

Smith, M. K. (2020). Naomi Klein: globalization, capitalism, neoliberalism and climate change, infed.org. [https://infed.org/mobi/naomi-klein-globalization-capitalism-neoliberalism-and-climate-change/. Retrieved: April 27, 2020].

Snyder, C. R. (1994). The Psychology of Hope. You can get there from here. New York: Free Press.

Snyder, C.R. (2000). Hypothesis: There is hope, in C.R. Snyder (ed.), Handbook of Hope Theory, Measures and Applications. San Diego: Academic Press.

Snyder, C. R., Rand, Kevin L., Sigmon, D. R. (2002). ‘Hope theory: A member of the positive psychology family’ in C. R. Snyder and S. J. Lopez, Shane J. (eds.). (2002). Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. pp. 257-276. Available: http://teachingpsychology.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/hope-theory.pdf. Retrieved April 2, 2016].

Solnit, R. (2016). Hope in the Dark. Untold histories, wild possibilities. 3e. Edinburgh: Canongate. [Page numbers refer to the epub version].

Tawney, R. H. (1953). The Attack and Other Papers. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Taylor, M. and Murry, J. (2020). ‘Overwhelming and terrifying’: the rise of climate anxiety, The Guardian February 6. [https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/feb/10/overwhelming-and-terrifying-impact-of-climate-crisis-on-mental-health. Retrieved February 11, 2020]

Terrill, R. (1973). R. H. Tawney and His Times. Socialism as fellowship. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Tillich, P. (1952). The Courage to Be. New Haven CT.: Yale University Press.

Turkle, S. (2015). Reclaiming Conversation. The power of talk in a digital age. New York: Penguin.

Turkle, S. (2017). Alone Together. Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. 3e. New York: Basic Books.

UNICEF (2016). Fairness for Children. A league table of inequality in child well-being in rich countries. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti.

Warnock, M. (1986). The Education of the Emotions. In D. Cooper (ed.) Education, values and the mind. Essays for R. S. Peters. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul.

Wilkinson, R and Pickett, K. (2018). The Inner Level. How more equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and improve everyone’s well-being. London: Penguin.

Woolcock, M. (2001). ‘The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes’, Isuma: Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1).

World Health Organisation (2016). Growing up unequal: gender and socioeconomic differences in young people’s health and well-being. Health behaviour in school-aged children (HSBC) Study. Health Policy for children and adolescents No 7. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/303438/HSBC-No.7-Growing-up-unequal-FULL-REPORT.pdf?ua=1. Retrieved: March 28, 2017].

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. London: Profile Books. [Pages details refer to Adobe digital numbering].

Acknowledgements: The material here on sanctuary and hope grew out of some work undertaken by Michele Erina Doyle and myself on Christian youth work for the Joseph Rank Trust some years back (see Doyle and Smith 1999) – and from recent work with Giles Barrow and others on the development of the role of the pedagogue within specialist education. The interest in community and education comes from much further back – work undertaken as part of a Department of Education Science (England) developmental project on political education – and from ongoing work with Tony Jeffs (see Jeffs and Smith 2020).

Picture – Make mine modern swap by Sarah Witherby | flickr ccbyncsa 2 licence.

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2020). Dealing with the ‘new normal’. Offering sanctuary, community and hope to children and young people in schools and local organizations. The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/dealing-with-the-new-normal-creating-places-of-sanctuary-community-and-hope-for-children-and-young-people/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K Smith 2020