Pierre Bourdieu’s exploration of how the social order is reproduced, and inequality persists across generations, is more pertinent than ever. We examine some key lessons for educators and pedagogues.

_______

contents: introduction • Pierre Bourdieu – life • habitus • field • capital • exploring reproduction • developing practice • conclusion • references and further reading • acknowledgements • how to cite this piece

Introduction

Pierre Bourdieu’s (1930-2002) theorizing has become a major focus for exploration within sociology. His work, and that of Michel Foucault, is amongst the most frequently cited of the late twentieth-century social theorists. New generations of researchers have continued to look to him (see, for example, Thatcher et. al. 2018) and with justification. Bourdieu’s exploration of how the social order is reproduced, and inequality persists across generations, is more pertinent than ever. The concepts he marshals shed considerable light, for example, on the dynamics at work for educators and pedagogues. Schooling, academic institutions and local structures were of great interest to him.

Here we examine three key notions informing his labour’s – habitus, field, and capital. We also explore their role in the reproduction of the social order, and in structuring people’s experience of education. As well as deepening our understanding, they can help us to develop practice. Sadly, the power of these ideas is often be lost in the abstraction and posturing of the academic industry that has grown up around Pierre Bourdieu. He was dismissive of grand theory and of theory for its own sake. Instead, he looked as he once commented, to developing ‘thinking tools visible through the results they yield’ (Wacquant 1989: 50). Fundamentally concerned with change and practice, Bourdieu’s efforts only make sense in the world when those that engage with them look to praxis – informed, committed action (even if he disliked the word – see below).

The notions of habitus, field, and capital are intricately connected so there is danger in approaching them separately. As Loic Wacquant put it, his ‘work which is so catholic and systematic in both intent and scope has typically been apprehended in “bits and pieces” and incorporated piecemeal’ (op. cit.: 27). This had been especially the case in the United States and in Britain. However, as Michael Grenfell (2014) has argued, by looking at the concepts one by one we can approach the whole – ‘how ultimately all of them are of one and the same epistemology’. More importantly, though, they are born of a coherent, critical, and committed stance or attitude to the world (what has been discussed as haltung within social pedagogy).

Before we turn to these ideas, we look briefly at Pierre Bourdieu’s life and the contexts in which he was operating. His experiences of schooling and local life when growing up had a profound impact on his focus and thinking, as did the time he spent in Algeria.

Pierre Bourdieu – life

One of the common ways of describing Pierre Bourdieu is as an outsider who became an insider. Whether he did become an insider is questionable. Richard Nice, who translated a lot of Bourdieu’s work, has suggested that there are ‘two versions of Bourdieu’s past. One is the mythical one in which he is the peasant boy confronting urban civilization, and the other, which he actually thought more seriously, is what it’s like to be a petit bourgeois and a success story’ (quoted by Silverstein and Goodman 2009: 6). His talent and disposition certainly enabled him to climb through the French education system. Being a ‘success story’ is not, however, the same as being an ‘insider’. Pierre Bourdieu described upwardly mobile students as “oblats miraculés,” or ‘dedicated servants of the academic cult, who achieve a miraculous trajectory but nonetheless feel like outsiders to the consecrated educational elite’ (Medvetz and Sallaz 2018: 2).

Homelife and schooling

Bourdieu was born in 1930 a small village in southern France – Denguin in the Béarn region (Pyrénées-Atlantiques). His grandfather had been a sharecropper but his father, who did not complete his schooling, had become a postman and then a postmaster. Bourdieu’s mother had remained in school until she was 16. Gascon, a regional dialect of Occitan which has now nearly disappeared, was spoken in the home. Looking back, Bourdieu talked about his petit-bourgeois family and rural background, and how it had made him ill at ease with class-based privilege and reluctant to separate himself from the “rank and file” (quoted in Silverstein and Goodman 2009: 8).

We know little or nothing about Pierre Bourdieu’s private life and his experiences at home and school. He went to the local elementary school and gained entry to the lycée in Pau – some 15 kilometres from his home in Denguin. Like many other students from distant villages, he had to board – and he has written briefly about this experience. As ‘a rural boarder in the lycée he was forced to wear a grey smock while the day pupils arrived in the latest attire’ (Grenfell 2014). They also made fun of his Gascon accent (see Bourdieu 2002). However, such was his academic ability and his commitment to studying that he was entered for – and passed – the entrance exam for the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris. The Lycée was one of the main feeders for the elite Parisian schools – the ‘Grandes Écoles’ and in 1951 he entered the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) to study philosophy. Louis Althusser and Jacques Derrida were there at the same time.

Pierre Bourdieu’s experiences of the schooling system, and the pressures and prejudices, focused around those from poorer backgrounds within elite educational institutions were significant both in terms of the foci of his work and his concern to generate tools for change. ‘A lot of what I’ve done has been in reaction to the École Normale,” he said in an interview with The New York Times. ‘I think if I hadn’t become a sociologist, I would have become very anti-intellectual. I was horrified by that world’ (quoted in Riding 2002).

Algeria

After graduating, Pierre Bourdieu worked as a lycée teacher before being conscripted into the French Army and deployed to Algeria in late 1955. There he was initially assigned to guarding military facilities and then to clerical work in the French document and information service in Algeria. Interestingly, this reassignment came following his parents making a request to a senior official in Algeria who came from their local, Béarn, region (Silverstein and Goodman 2009: 9). Bourdieu was opposed to colonialism and supported Algerian nationalist efforts to gain independence (their war had begun in 1954 and was to last until 1962). He was also concerned about the ‘blind submission’ of soldiers to authority, and increasingly interested in Algerian society. The move to the document and information service allowed him to follow this growing interest. He was both able to meet leading scholars and access the government’s Algerian library.

Paris

On his return to France, Pierre Bourdieu became an assistant to Raymond Aron who was known both as a writer and journalist, and as a social scientist (at this time he held a professorship in political science at the Sorbonne in Paris). However, as Bourdieu put it, ‘First, I went to Lille, where I gave this strange kind of course on the history of sociological thought: Marx, Durkheim, Weber, Pareto –outrageous, an insane job’ (Bourdieu, P., Schultheis, F. and Pfeuffer, A. 2011). He was at University of Lille from 1961 to 1964 and during this period he married Marie-Claire Brizzard (1936-2014) (in November 1962).

Raymond Aron, like Bourdieu, was interested in Max Weber’s work. However, ‘it soon became clear to me that Aron and I had very different ways of looking at things: my Weber was opposed to Aron’s Weber. It is staggering that Aron was hardly familiar at all with Weber’s Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft’ (op. cit.). One also wonders how Bourdieu managed more generally around Aron. Didier Eribon, who also came from a non-elite background, had described Aron as follows:

I only met him once in my life, and immediately felt a strong aversion towards him. The very moment I set eyes on him, I loathed his ingratiating smile, his soothing voice, his way of demonstrating how reasonable and rational he was, everything about him that displayed his bourgeois ethos of decorum and propriety, of ideological moderation. In reality, his writings are filled with a violence that those at whom it is directed would not be able to avoid feeling were they ever to come across it. It suffices to read—but there are other choices too—the pages he wrote about the working-class strikes in the 1950s. People have praised his lucidity because he was anti-communist while others still blindly supported the Soviet Union. But this is wrong! He was anti-communist because of his hatred of the working class, and he set himself up as the political and ideological defender of the bourgeois establishment, defending against anything having to do with the aspirations or the political activities of the working class. Basically, his pen was for hire: he was a soldier in the service of those in power helping them to maintain their power. (2018: 520)

… many of the seemingly personal choices of everyday life—what to wear, to eat, to display on one’s walls, or to make of the latest blockbuster movie—could be explained through reference to the overall class structure (in particular, the overall volume of one’s capital and the relative composition of cultural and economic capital). (op. cit.)

Many of Bourdieu’s books at this time were published by Les Editions de Minuit. Somehow, alongside the writing, Pierre Bourdieu also managed to edit one of their book series – Le Sens Common. Amongst the books were translations of key texts including work by Erving Goffman. He also had three sons – Jérôme, Emmanuel, and Laurent!

Bourdieu became Chair in Sociology at the Collège de France in 1981 – and was awarded the gold medal of the CNRS – the French national research centre (Grenfell 2014: 25). Landmark texts followed including Homo academicus (1984) and Raisons pratiques. Sur la théorie de l’action (Practical Reason. On the theory of action) (1994 | 1998).

In this later period, Pierre Bourdieu became more heavily involved in political debates. During the 1980s this included being a member of a committee set up by the Socialist government under François Mitterand to review the direction and curriculum of the French education system. However, he became best known as a public intellectual via his critique of the rise of neoliberalism and the impact it had upon economic and social policies and debates (see, for example, Bourdieu 2008).

Pierre Bourdieu died from cancer on January 23, 2002. He was 71. His death was the lead story on French TV news and ‘ran with expressions of grief and loss from France’s president, prime minister, trade union leaders, and a host of other dignitaries and scholars’ (Calhoun 2002).

Habitus

To begin our journey through some of the key elements of Pierre Bourdieu’s thinking it is worth starting with four key points.

First, Bourdieu was steeped in the work of the founding theorists of sociology such as Durkheim and Weber, and in the changing currents of philosophy and social theory more broadly. He could draw upon philosophers such as Edmund Husserl (1939 | 1973), anthropologists like Durkheim’s nephew – Marcel Mauss (1950 | 1966), and social theorists concerned with the ‘civilizing process’ like Norman Elias (1994).

Second, his approach involves developing not so much a theory, as a method. This consisted ‘essentially in a manner of posing problems, in a parsimonious set of conceptual tools and procedures for constructing objects and for transferring knowledge gleaned in one area of inquiry into another’ (Wacquant 1992: 5).

Third, he saw the task of sociology as uncovering ‘the most profoundly buried structures of the various social worlds which constitute the social universe, as well as the “mechanisms” which tend to ensure their reproduction or their transformation’ (Bourdieu 1989: 7).

Fourth, rather than debating the priority of structure or agent, or system or actor, Bourdieu, ‘affirms the primacy of relations. In his view, such dualistic alternatives reflect a common-sensical perception of social reality of which sociology must rid itself’ (Wacquant 1992: 15).

These capacities and orientations, combined with his concern to understand the forces that lead to the reproduction of social inequality, meant that he both identified the significance of habitus and could develop it as a ‘thinking tool’ that might lead to change.

The Latin word habitus can be translated as habit. However, that narrows its meaning and makes it passive. It is better approached via the Ancient Greek notion of hexis. Hexis is an active condition and something more than a disposition (diathesis) according to Aristotle. It entails a readiness to sense and know (Sachs 2001) that in everyday life is often constrained. This leads to a narrowing perception of what is possible for people within different social groups and helps to explain, for example, ’how working-class kids’ working-class jobs’ (Willis 1977). It is to this that Bourdieu pays special attention.

Experientially, we often feel we are free agents, yet base everyday decisions on assumptions about the predictable character, behaviour and attitudes of others. Sociologically, social practices are characterized by regularities… Bourdieu asks how social structure and individual agency can be reconciled, and (to use Durkheim’s terms) how the “outer” social and “inner” self, help to shape each other. (Maton 2014: 48)

As Kark Maton also comments, habitus is central to Bourdieu’s approach, and to his originality and contribution to social science. ‘Yet habitus is also one of the most misunderstood, misused and hotly contested of Bourdieu’s ideas’ (2014: 48).

Bourdieu defines habitus as ‘a property of actors (whether individuals, groups or institutions) that comprises a “structured and structuring structure” ‘(1987|1994: 131). It is a system of dispositions.

The word disposition seems particularly suited to express what is covered by the concept of habitus… It expresses first the result of an organizing action, with a meaning close to that of words such as structure; it also designates a way of being, a habitual state (especially of the body) and, in particular, a predisposition, tendency, propensity or inclination. (Bourdieu 1972|1977: 214, n l)

There are five things to note here.

First, Bourdieu is looking at habitus as a habitual state, not a habit. It is a way of being.

Second, ‘being’ (and habitus) are relational concepts. Being involves relationships with others and the environments we are part of.

Third, we come back to hexis and the readiness to sense and know. While there may be powerful forces acting to contain this, there is always the chance that it will shine through. The ‘structuring structure’ is not total. There is the possibility of learning and change, as Jürgen Habermas argued. In dialogue, there is ‘a gentle but obstinate, a never silent although seldom redeemed claim to reason’ (1979: 3).

Fourth, this system of dispositions points and pushes us towards certain perceptions, appreciations, and practices. Defined by such a social trajectory, habitus can be considered as:

… a subjective but not individual system of internalized structures, schemes of perception, conception, and action common to all members of the same group or class and constituting the precondition for all objectification and apperception: and the objective coordination of practices and the sharing of a world-view could be founded on the perfect impersonality and interchangeability of singular practices and views. (Bourdieu 1972|1977: 86)

Bourdieu’s concern to overturn binary thinking within social theory – especially around agency/structure and subjectivism/objectivism – provides an important and debated dynamic. Objective structures, as Graham Schambler (2015) has suggested, constrain thought, action, and interaction – and the way we represent the world. ‘People’s representations, in turn, affect objective structures.’ These tensions or dialectics are at play in all that Bourdieu writes about the emergence of practice (see below). Unfortunately, the way in which Bourdieu has presented these ideas has meant that some commentators interpreted his efforts as an attempt to defuse these tensions rather than recognize their relational significance (see Martin 2003).

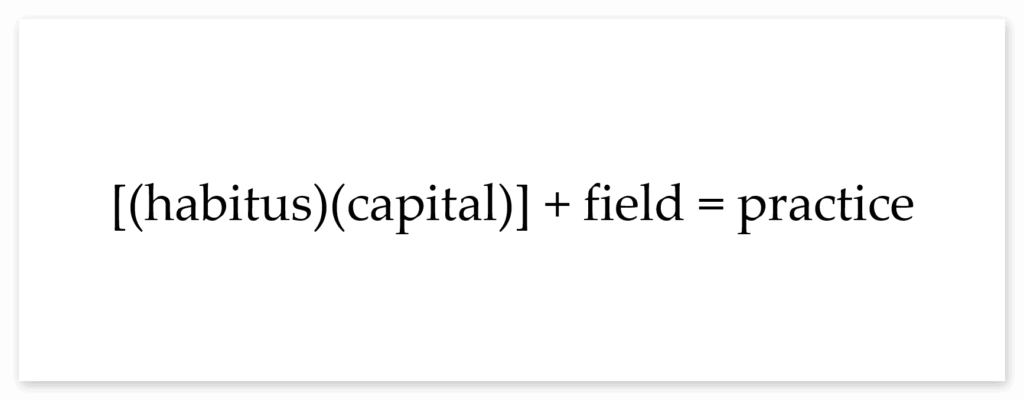

Last, and certainly not least, habitus only makes sense when it is related to his other concepts – field, capital, and practice. It does not stand on its own. Bourdieu was later to express this in a formula in Distinction (1977|1984: 101). This was probably included more as a way of inviting people to think about the relationship between the phenomena than as a summation of an actual theory of practice. In fact, Bourdieu does not take us much further forward concerning the relationship in the book, but the formula certainly invites discussion.

Maton comments, ‘This equation can be unpacked as stating: one’s practice results from relations between one’s dispositions (habitus) and one’s position in a field (capital), within the current state of play of that social arena (field) (2014: 51).

Field

Bourdieu approaches the notion of field as a social space in which interactions, transactions and events take place. Patricia Thomson comments:

In English, the word “field” may well conjure up an image of a meadow. Perhaps it is early summer, and the meadow is a profusion of wildflowers and grasses surrounded by a dark mass of trees. In French, the word for this kind of field is le pré. However, Bourdieu did not write about pretty and benign les prés, but rather le champ, which is used to describe, inter alia, an area of land, a battlefield, and a field of knowledge. There are many analogies for Bourdieu’s champ: (1) the field on which a game of football is played (le terrain in French); (2) the field in science fiction, (as in “Activate the force-field, Spock”); or even (3) a field of forces in physics. Bourdieu’s concept of champ, or field, contains important elements of all of these three analogies, while equating to none of them.

If we follow this through, we can see that Pierre Bourdieu – as before – is developing a tool for thinking. Like a football pitch a field it is something with boundaries. However, within it shapes change, and different forces are at play. Field in this way is different from a system, but an idea that we can use to help us make sense of different situations.

Kurt Lewin had made a significant prior contribution to field theory. For him, a ‘field’ was ‘the totality of coexisting facts which are conceived of as mutually interdependent’ (Lewin 1951: 240). Individuals were seen to behave differently according to the way in which tensions between perceptions of the self and of the environment were worked through. The whole psychological field, or ‘life space’, within which people acted had to be viewed to understand behaviour (see Smith 2001). Bourdieu and his various collaborators shared significant concerns with Lewin. They focused on space – whether social or physical – as a relational phenomenon. They questioned ‘the existence of an absolute (social or physical) space and consequently of individual objects or agents existing independently of a set of relations’ (Hilgers and Mangez 2015: 4-5). However, while Lewin broadly looked to social psychology, Bourdieu was concerned with stratification and domination. He was interested in the nature of social space and the relation between different fields and any relative autonomy and power they might have.

A great deal of Bourdieu’s later work involved the exploration of contrasting fields of practice – and fields within fields. This included investigations of schools and universities, cultural industries, science, and housing. One study, on television, contained this oft-quoted summation of his understanding of field. It is:

a structured social space, a field of forces, a force field. It contains people who dominate and people who are dominated. Constant, permanent relationships of inequality operate inside this space, which at the same time becomes a space in which various actors struggle for the transformation or preservation of the field. All the individuals in this universe bring to the competition all the (relative) power at their disposal. It is this power that defines their position in the field and, as a result, their strategies. (Bourdieu 1998b: 40–41)

Bourdieu also pointed to the steps that needed to be taken to explore a field:

First, one must analyze the position of the field vis-a-vis the field of power….

Second, one must map out the objective structure of the relations between the positions occupied by the agents or institutions who compete for the legitimate form of specific authority of which this field in the site.

And, third, one must analyze the habitus of agents, the different systems of dispositions they have acquired by internalizing a determinate type of social and economic condition, and which find in a definite trajectory within the field under consideration a more or less favorable opportunity to become actualized. (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992: 105-6)

Various criticisms have been made of field theory – and Pierre Bourdieu’s reading of it. Here we just need to note three further things about the approach he takes.

First, as Patricia Thomson (2014) and John Levi Martin (2003) have noted, this approach can yield many fields, often with very fuzzy boundaries. However, it is easy to fall into the trap of seeing a field as a representation of a formal system rather than an analytical approach.

Second, ‘field’ is a tool for thinking. Bourdieu both wants to explore, and encourage, reflexivity. In this case, he is concerned with the capacity of people (agents) in different fields to see the various forces at work in their socialization and how they may either change their situation and/or the social structure itself. It is also about something more – and this is linked to habitus – the disposition to strive for change.

Third, and linked to the above, Pierre Bourdieu was interested in the relative autonomy of agents and field within fields. Having more control might well be linked to social characteristics such as class, ethnicity, and gender, and to the location and nature of the field. Here, the third of our components – capital – is of special importance.

Capital

There are often problems when one imports a concept born of one setting into another where there are rather different forces and concerns. Taking ‘capital’ from the economic sphere and using it to describe things like networks and relationships (social capital) and familiarity with ‘valued’ cultural forms (cultural capital) can smuggle in unhelpful meanings and be taken too literally. As John Field (2017) has suggested, the central idea of social capital is that ‘social networks are a valuable asset’. It is a metaphor implying that ‘connections can be profitable; like any other form of capital, physical or financial, you can invest in it, and you can expect a decent return on your investment’ (op. cit.: 13). Some tried to make it more concrete and measurable – much as economists did with human capital in the 1960s (see, for example, Becker 1964). The result was often rather crude and unhelpful ‘bean-counting’ that both tended to dehumanize and to ignore the meaning of social behaviour and processes.

Thankfully, Bourdieu stayed focused on the use of different forms of ‘capital’ as a tool for thinking. He saw ‘capital’ as a helpful metaphor to shed light on the continual process of remaking of the social order.

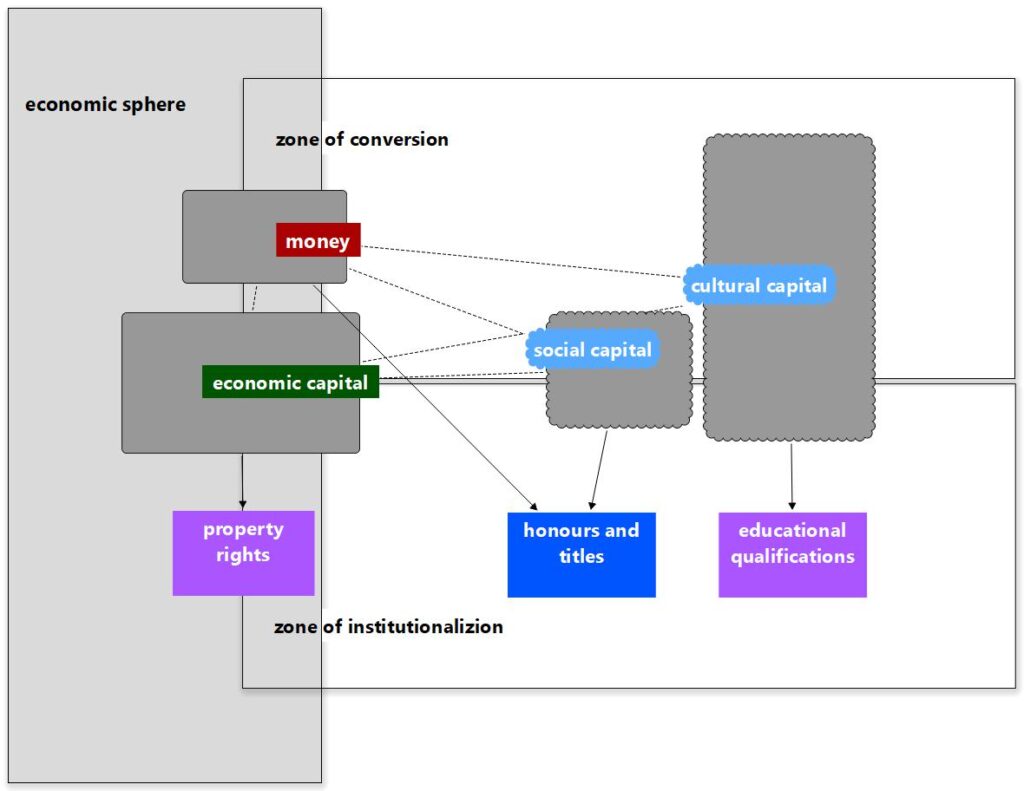

[C]apital can present itself in three fundamental guises: as economic capital, which is immediately and directly convertible into money and may be institutionalized in the forms of property rights; as cultural capital, which is convertible, on certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalized in the forms of educational qualifications; and as social capital, made up of obligations (‘connections’), which is convertible, in certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalized in the forms of a title of nobility. (Bourdieu 1986: 242]

Three things need noting here.

First, the possession or not, of different forms of ‘capital’ could be a significant factor in the ways that people experience education and access to opportunities in general.

Second, Bourdieu is highlighting two key processes – conversion and institutionalization.

- Economic capital institutionalized in the form of property rights and can be converted into money (and used, for example, to buy private schooling which in turn builds cultural capital which in turn is institutionalized in educational qualification. It can also buy honours and titles.

- Social ‘capital’ can be converted via the membership of the ‘right’ networks and the use of ‘connections’ into economic capital and money and institutionalized in the form of honours and titles.

- Cultural ‘capital’ can be institutionalized in the form of educational qualifications and, similarly, converted into economic capital and money.

Third, economic capital is not metaphorical in the way that social and cultural ‘capital’ are. It is made up of concrete things like gold and diamonds, and paper or electronic items like shares and bank accounts. Their worth can be measured in currencies such as the dollar, yen and euro. Economic capital is, in short, money that has been invested or held to retain wealth or to generate income. Perhaps, the easiest way to remind us of this is to use quotation marks around social ‘capital’ and cultural ‘capital’. In the diagram, it is represented as being part of the economic sphere.

Social and cultural ‘capital ‘

The growth of interest in the notion of ‘social capital’ over the last three decades can be attributable to the very different work of three writers: Pierre Bourdieu, Robert Putnam (2000) and James Coleman (1988). Bourdieu, while not being the first to use the term, was the first to ‘produce a systematic conception of social capital’ in (see, for example, Bourdieu 1977) (Field 2017). He refined his thinking over the years – and he came to see social ‘capital’ as: ‘the sum of resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual or a group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992: 119).

Pierre Bourdieu suggests that cultural ‘capital’ is probably best understood as ‘informational capital’ if we are to understand its full reach. Cultural ‘capital’ is ‘primarily legitimate knowledge of one kind or another’ (Jenkins 1992 – Chapter 4). In his 1986 paper, The forms of capital, Bourdieu suggests that cultural capital can exist in three forms:

… in the embodied state, i.e., in the form of long-lasting dispositions of the mind and body; in the objectified state, in the form of cultural goods (pictures, books, dictionaries, instruments, machines, etc.), which are the trace or realization of theories or critiques of these theories, problematics, etc.; and in the institutionalized state, a form of objectification which must be set apart because, as will be seen in the case of educational qualifications, it confers entirely original properties on the cultural capital which it is presumed to guarantee. (Bourdieu 1986: 242)

Bourdieu (1979, 1984) had earlier argued that ‘taste’ in a society is largely determined by those with a high level of cultural capital.

One of the areas that Bourdieu focused on was schooling. Children enter the school system with different amounts of capital; they do not start and continue within the system with the same resources and advantages. The result is, as Bourdieu argues, that the system then largely reproduces advantage. Those with the ‘luck’ of being born into families with money and the right cultural capital, progress further than those who are not. They do not have an inherent ability and advance on merit, but start out with, and are supported by those possessing the right mix of economic and cultural capital.

Somewhat worryingly, the English school inspection framework has appropriated the term to make judgements about the performance of schools.

As part of making the judgement about the quality of education, inspectors will consider the extent to which schools are equipping pupils with the knowledge and cultural capital they need to succeed in life. Our understanding of ‘knowledge and cultural capital’ is derived from the following wording in the national curriculum:

It is the essential knowledge that pupils need to be educated citizens, introducing them to the best that has been thought and said and helping to engender an appreciation of human creativity and achievement. (Ofsted 2019: 43)

Not only is this requirement what Diane Reay called ‘a crude, reductionist model of learning, both authoritarian and elitist’, it also misses the point that Bourdieu was making. ‘The key elements of cultural capital are entwined with privileged lifestyles rather than qualities you can separate off and then teach the poor and working classes’ (Reay quoted by Mansell 2019. See, also, Reay 2017). Schooling has historically worked to strengthen inequality and it will take rather more than ‘cultural capital lessons’ to alter that.

Symbolic capital

Before leaving this brief discussion of capital, it is necessary to highlight one further use Bourdieu makes of it: the notion of symbolic capital. As we have seen, the term ‘capital’ is usually associated with exchanges within the economic sphere. Bourdieu is interested in a wide range of cultural exchanges and it is in this context he uses the notion of symbolic capital. Symbolic capital is the result of what the Roman Catholic church has called transubstantiation. Economic capital changes into symbolic capital. In turn, social, and cultural capital can be viewed as sub-types of symbolic capital – and have been joined by the discussion of other forms found in different fields such as linguistic capital, and scientific and literary capital.

Rob Moore (2015: 114) has helpfully highlighted a key difference between economic and symbolic capital. In the first:

… the instrumental and self-interested nature of the exchange is transparent. Mercantile exchange is not of intrinsic value, but is always only a means to an end (profit, interest, a wage, etc). Bourdieu contends that this is also true for other forms of symbolic capital, but that they, in their distinctive ways, deny and suppress their instrumentalism by proclaiming themselves to be disinterested and of intrinsic worth.

The significance of the approach that Bourdieu takes to symbolic capital is that it allows him to explore the differences between social groups and ‘qualitative differences in forms of consciousness within different social groups’ (op. cit.: 113).

Exploring reproduction

… schooling operated to sort and sift children and young people into various educational trajectories – employment, training and further education, and various kinds of universities. The practices of differentiation included antidemocratic pedagogies, taken-for-granted use of elite discourse and knowledges, and a differentiated system of selection and training of teachers. Education was, he suggested, a field which reproduced itself more than others, and those agents who occupied dominant positions were deeply imbued with its practices and discourses. (Thompson 2014: 89)

As Pierre Bourdieu’s progress through the French educational system shows, some individuals from outside dominant classes and wealthy groups can get through, and the offspring of some in the upper echelon do not. Historically, the latter might well have ‘inherited’ progression but now they must demonstrate achievement in the schooling system. However, they start with a tremendous advantage in terms of economic, social and cultural capital.

[W]ealthy families … first convert their material capital into cultural capital, whose display is then rewarded by success in the system of elite schools. While the informal varieties of cultural capital that the children of the upper class acquire at home early in life (such as a particular accent or knowledge of the arts) serve them well in the school system, true hard work is required of these inheritors, and many in fact fail to reconvert their family’s cultural capital into material capital (via prestigious degrees leading to top jobs in the state or private sector). (Medvetz and Sallaz 2018: 2).

The task of sociology, Pierre Bourdieu argued, is ‘to uncover the most profoundly buried structures of the various social worlds which constitute the social universe, as well as the “mechanisms” which tend to ensure their reproduction or their transformation’ (1989: 7. Also quoted in Bourdieu and Wasquant 1992: 7). We could add that one of the central tasks of pedagogues and educators should be to similarly work with people to:

- Explore the buried structures of the social worlds and activities they participate in.

- Recognize the ways in which their dispositions and experiences are replicating inequalities and constraining their ability – and that of others – to flourish.

- Develop ways of thinking and acting that allow them to change the situations and systems there are involved in.

The possibility of this creating major change is limited. In part, this is because of the reproductive power of the schooling and college systems already noted, but also as those systems are just one, albeit important, element of the making and remaking of inequality. This doesn’t mean that we should not try.

Developing practice

Bourdieu viewed the notion of praxis as, overall, ‘pompously theoretical’ (at least in French) and talked of ‘practice’ (1987|1994: 22). Unfortunately, there is no straightforward answer as to what he meant by ‘practice’. As a starting point, we can think of practices as being acts embodying shared rules and processes. Examples here would include everyday things like greeting people, queuing for, and getting on, a bus etc. Certainly, one of the things that Pierre Bourdieu was interested in here was knowing how to ‘play the game’ or what he called ‘practical sense’ (his work The Logic of Practice [1990] had the original title Le Sense pratique [1980]).

This equation can be unpacked as stating: one’s practice results from relations between one’s dispositions (habitus) and one’s position in a field (capital), within the current state of play of that social arena (field)… Practices are thus not simply the result of one’s habitus but rather of relations between one’s habitus and one’s current circumstances. Put another way, we cannot understand the practices of actors in terms of their habituses alone – habitus represents but one part of the equation; the nature of the fields they are active within is equally crucial.

Alan Warde (2004: 5-6) has argued that Bourdieu never really got to grip with ‘practice’. In Distinction, for example, Bourdieu uses practice in three senses:

- In contrast to theory. ‘Practical conduct neither requires nor exhibits the level of conscious reflexive thought characteristic of theoretical reason’.

- To identify an entity formed around an activity – much like Praktik (‘a coordinated, recognizable, and institutionally supported practice’).

- The performance or carrying out of some action or other.

In Logic of Practice (Bourdieu 1990) Warde identifies six different uses (op. cit.: 30). Rather than being a clarification of his thinking in this area, he suggests it might rather indicate the extent to he appears to have lost interest in practice as an organizing idea. This is a shame both as the notion of practice can be helpfully reclaimed – and it strengthens the ‘thinking tool’ Pierre Bourdieu has created.

Practice and praxis

Andreas Reckwitz has provided us with a starting point – the distinction between ‘practice’ and ‘practices’ (drawing on the German Praxis and Praktik):

’Practice’ (Praxis) in the singular represents merely an emphatic term to describe the whole of human action (in contrast to ’theory’ and mere thinking). ‘Practices’ in the sense of the theory of social practices, however, is something else. A ‘practice’ (Praktik) is a routinized type of behaviour which consists of several elements, interconnected to one other: forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, ‘things’ and their use, a background knowledge in the form of understanding, know-how, states of emotion and motivational knowledge. (2002: 249-50)

Focusing on practice as Pratik when looking to the relationship between it and field, habitus and capital would seem to be a sensible way forward. Pratik provides both historical force and relationship – as Alistair Macintyre recognized regarding virtue and moral theory:

To enter into practice is to enter into a relationship not only with its contemporary practitioners but also with those who have preceded us in the practice, particularly those whose achievements extended the reach of the practice to its present point. It is thus the achievement and, a fortiori, the authority, of a tradition which I then confront and from which I have to learn. (1985: 194).

Macintyre goes on to argue that no practices can survive for any time unless underpinned by institutions. These institutions, in turn, can corrupt practice unless practitioners have the space to organize, understanding and analysis, and a disposition that involves virtues like justice, courage and truthfulness. All of which sounds like praxis in a sense other than ‘an emphatic term’ – informed, committed action.

What, then, are we to do as educators?

Ourselves, others and the world of which we are a part

Education is here taken to mean ‘the wise, hopeful and respectful cultivation of learning undertaken in the belief that all should have the chance to share in life’ (Smith 2015, 2020). Bearing this in mind, there are clearly different aspects of Bourdieu’s thinking that we need to work on. Making sense of educational practice entails both looking to habitus, field and capital – and to:

- Ourselves – and the process of becoming more reflective and reflexive practitioners.

- Others – changing the way we work with learners, participants and significant others like parents, siblings and peers, and with immediate colleagues and managers.

- Wider systems – engaging with local networks and more distanced professional, policy-making, and political systems.

In this way, we can make a start – and highlight some initial areas for development.

Exploring reproduction in the practice of education

The first, and obvious, point to make is that the reproduction of the social order needs to be a focus when reflecting on our own practice and processes – and that of the institutions we function within. It should feature within staff training, discussions of policy and practice, and how organizations are managed. Furthermore, it must also be a key focus for exploration by and with learners, students and other participants. Within schools, for example, it should be a central element of curricula, and something that is part of conversations in tutor groups, on corridors and other, more informal, spaces. The former is less a case of introducing new curricula elements, so much as problematizing existing ones. The latter does entail shifting, and making the case for new, resources to create spaces where children and young people can experience much-needed sanctuary, community, and hope. This also involves recognizing that teachers often lack the capacity, orientation, and skills to do this – and that it is necessary to employ and value specialist educators and pedagogues.

Second, Bourdieu’s discussion of habitus (and hexis) does have some profound implications for the practice of teachers, specialist educators and pedagogues. Within informal education and social pedagogy, there has long been an emphasis on the bearing and attitude of the worker. The German term for this is Haltung. It is also translated as stance, posture or mindset. Pedagogues act in the belief that, as Bertold Brecht put it some time ago, ‘When taking up a proper bearing, truth …will manifest itself.” (BBA 827/07, ca. 1930, in Steinweg 1975: 101).

When looking at what pedagogues and informal educators do, it involves – in Aristotle’s terms – a leading idea (eidos); what Bourdieu refers to as disposition and we have discussed as ‘haltung’ (here it is phronesis – a moral disposition to act truly and rightly, and the ability to reflect upon, identify and decide on ends that cultivate flourishing); dialogue/interaction; and praxis (informed, committed action) (Carr and Kemmis 1986; Grundy 1987).

Pedagogy in this form is largely a non-curricula practice – it is informal education. Teaching is an interlude rather than a defining feature. The challenge for formal education and teachers is how to embrace the first two elements above – and to allow it to guide the way in which curricula are addressed, and learning facilitated. [See What is curriculum? This article explores different models that may be required].

Bourdieu’s appreciation of hexis – a readiness to sense and know – allows us to take a further step forward – both in terms of the processes discussed above, and in what we might seek to do when working with learners and participants. Such qualities can be seen as being at the core of the haltung and processes of pedagogues and informal educators. There is a strong emphasis upon being in touch with feelings, of attending to intuitions and seeking evidence to confirm or question what we might be sensing. A further element is also present – a concern not to take things for granted or at their face value. Many teachers also have these qualities, but it could be a stronger feature of training, and of non-managerial supervision within schooling. The reason why this is necessary is not just to improve their practice, but to be able to work with children, young people, and adults to cultivate hexis themselves. It is a vital part of the process of coming to recognize just how their lives are being channelled in particular directions, to question ‘structuring structures’ – and sense another way is possible.

Third, we need to recognize the usefulness of field and capital as tools to explore the processes we, and those we are working with, are living through. In the case of the former, it is a case of exploring our, and others’, capacity, and readiness (disposition) to recognize and do something about the various forces of socialization at work in different areas of life and identity. More specifically, it involves recognizing shared experiences and exploring how to join with others so that all may flourish. Here there is an obvious and a direct connection here with what Bourdieu discusses as social capital. In addition, there are questions around the sorts of cultural capital that schools, colleges and local organizations cultivate. These were laid bare – once again – by the way in which qualifications authorities in the UK employed algorithms to review and change estimated grades for students in 2020. In England, Ofqual’s data revealed substantial differences between school types in the grades awarded.

The proportion of A* and As awarded to independent schools rose by 4.7 percentage points, more than twice as much as state comprehensive schools. State sixth form colleges did even worse with a rise of 0.6 percentage points, compared with the increase of 2.3 points in England as a whole. (Adams and McIntyre 2020)

The algorithm favoured, for example, students in small classes taking less popular courses such as Latin, which are more common in private schools (Adams 2020).

As Dominic Rushe (2020) has written in the context of Covid-19:

“We are all in this together” may be the rallying cry for the pandemic but the truth is the poor, and particularly people of color, have been devastated by coronavirus and its attendant recession while the wealthy have weathered it and in some cases made huge gains.

We need to see schooling as a profoundly political and divisive experience.

Conclusion

As Ritzer (2003) put it, one of the impressive things about Pierre Bourdieu’s work is that he ‘not only built bridges between theory and research, he crossed the bridges he built to test their strength and durability’. His concern with social reproduction in schooling and college systems remains deeply relevant. It is no accident, for example, that the big expansion of higher education in recent years has coincided in the UK and many other countries with a reduction in social mobility (Major and Machin 2018). Bourdieu’s focus on developing tools for thinking such as habitus, field and capital allow us to think about taking tentative steps to unsettle the automatic reproduction of the social order.

It may be, in the end, that as Bourdieu often appears to be saying, we might not have much room for agency. However, as we have seen, the ‘structuring structure’ is not, and cannot be, total. We could not call ourselves educators if we do not try to work so that all should have the chance to share in life.

References and further reading

Introducing Bourdieu

If you have not encountered the work of Pierre Bourdieu before, then listening to this BBC Radio 4 programme on his work in the Thinking Aloud series presented by Laurie Taylor is a good place to begin. It includes contributions by Diane Reay, Derron Wallace, and Kirsty Morrin (2016). Download: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07gg1kb.

Graham Schambler also provides another brief and helpful starting point in his blog:

Schambler, Graham (2015). Sociological Theorists: Pierre Bourdieu. [http://www.grahamscambler.com/sociological-theorists-pierre-bourdieu/. Retrieved: July 22, 2020].

For an introduction of key themes within Bourdieu’s work try:

Grenfell, Michael ed. (2014). Pierre Bourdieu. Key Concepts. Abingdon: Routledge. One of the best starting points for approaching Bourdieu’s thinking. The book looks at each of Bourdieu’s central ideas.

Lastly, Didier Eribon’s Returning to Reims provides a great example of a conversation with Bourdieu’s ideas – and reflection on a parallel trajectory through a French class system:

Eribon, D. (2018). Returning to Reims. Translated by Michael Lucey. London: Allen Lane. First published in French in 2009 as Retour à Reims. Paris: Fayard.

References

Adams, R. (2020). GCSEs: 2 million results set to be downgraded, researchers warn, The Guardian, August 14. [https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/aug/14/gcses-2-million-grades-set-to-be-downgraded-researchers-warn. Retrieved August 14, 2020].

Adams, R. and McIntyre, N. (2020). England A-level downgrades hit pupils from disadvantaged areas hardest. The Guardian August, 13. [https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/aug/13/england-a-level-downgrades-hit-pupils-from-disadvantaged-areas-hardest. Retrieved August 15, 2020].

Atkinson, W. (2017). Beyond Bourdieu. Cambridge: Polity.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1958). Sociologie de l’Algérie. (Revised edition, 1961.) Paris: Que Sais-je.

Bourdieu, Pierre., Darbel, A., Rivet, J. P. and Seibel, C. (1963). Travail et travailleurs en Algérie. Paris: Mouton.

Bourdieu, Pierre and Sayad, A. (1964). Le déracinement, la crise de l’agriculture traditionelle en Algérie. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

Bourdieu, Pierre., Passeron, Jean-Claude. and Chamboredon, Jean-Claude. (1968). Le Métier de sociologue, préalables épistémologiques. Paris, Mouton: Bordas.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1972|1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First published in French as Esquisse d’une théorie de la pratique, précédé de trois études d’ethnologie kabyle, (1972).

Bourdieu, P. (1977). ‘Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction’, in J. Karabel and A. H. Halsey (eds), Power and Ideology in Education. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 487–511.

Bourdieu, Pierre. and Passeron, Jean-Claude (1979) The Inheritors, French Students and their Relation to Culture. Richard Nice (trans.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. First published in 1964 as Les héritiers, les étudiants et la culture. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1979|1984). Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translation by Richard Nice. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. First published in French as La Distinction. Critique sociale de judgment. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit (1979).

Bourdieu, Pierre (1980|1990). Logic of Practice. Richard Nice (trans.). Cambridge: Polity Press. First published in French as Le sens pratique. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1986a). The forms of capital in J. Richardson (ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (New York, Greenwood), 241-258. [https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/fr/bourdieu-forms-capital.htm. Retrieved September 23, 2019].

Bourdieu, Pierre (1986b). The Production of Belief: Contribution to an Economy of Symbolic Goods, Media, Culture and Society: A Critical Reader, R. Collins, J. Curran, N. Garnham & P. Scannell (eds). London: Sage.

Bourdieu, P. (1987|1994). Choses dites. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit. In Other Words: Essays Towards a Reflexive Sociology, M. Adamson (trans.). Cambridge: Polity.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1988). Homo Academicus, P. Collier (trans.). Cambridge: Polity. Originally published in 1984 as Homo academicus. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1989). La noblesse d’Etat. Grands corps et Grandes écoles. Paris: Editions de Minuit.

Bourdieu, Pierre and Passeron, Jean-Claude. (1990a). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture (Theory, Culture and Society Series) 2e. London: Sage. (First published in French in 1970 as: La Reproduction. Éléments pour une théorie du système d’enseignement. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit) and in English in 1977.

Bourdieu, Pierre with others (1990b). Photography. A Middle-brow Art, S. Whiteside (trans.). Cambridge: Polity. Originally published in 1965 as Un Art moyen, essai sur les usages sociaux de la photographie. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

Bourdieu, Pierre and Alain Darbel and Dominique Schnapper., A. (1990c). The Love of Art. European Art Museums and their Public, C. Beattie & N. Merriman (trans.). Cambridge: Polity. Originally published in 1966 as L’Amour de l’art, les musées d’art et leur public. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

Bourdieu, Pierre and Wacquant, Loic J. D. (1992). An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1998). Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action. Translation by Randal Johnson. Cambridge: Polity. Originally published in French in 1994 as Raisons pratiques. Sur la théorie de l’action. Paris: Seuil.

Bourdieu, Pierre (2002). “Pierre par Bourdieu”. Le Nouvel Observateur (31 January): 30–31.

Bourdieu, Pierre (2008). Political Interventions: Social Science and Political Action. Edited by Franck Poupeau and translated by David Fernbach. London: Verso. First published in 2001 as Interventions, 1961 -2001. Science sociale and actions politique by Paris: Editions Agone.

Bourdieu, P., Schultheis, F. and Pfeuffer, A. (2011). With Weber against Weber: In Conversation with Pierre Bourdieu in Susen, S. and Turner, B. S. (Eds.), The Legacy of Pierre Bourdieu: Critical Essays. (pp. 111-124). London, UK: Anthem Press. [http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/18955/1/3.%20CRO%20(Accepted%20Version)%20P.%20Bourdieu,%20F.%20Schultheis,%20A.%20Pfeuffer%20(2011)%20%E2%80%98With%20Weber%20Against%20Weber.%20In%20Conv%20with%20PB%E2%80%99.pdf. Retrieved September 28, 2019].

Carhoun, Craig (2002). On learning of the death of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. [Pierre Bourdieu in Context] [http://www.nyu.edu/classes/bkg/objects/calhoun.doc. Retrieved: September 30, 2019].

Coleman, J. C. (1988) ‘Social capital in the creation of human capital’ American Journal of Sociology 94: S95-S120.

Dendasck, C. V. and Lee, G. F. (2016). Concept of Habitus in Pierre Bourdieu and Norbert Elias. Multidisciplinary Core scientific journal of knowledge. Vol. 3, 1 Year. May 2016. P. 1-10. ISSN 24480959

Elias, N. (1994) The Civilizing Process. Sociogenetic and Psychogenetic Investigations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Field, J. (2017). Social Capital 3e. Abingdon: Routledge. [Page numbers are from the epub version).

Goodman, J. E. and Silverstein, P. A. (eds.) (2009). Bourdieu in Algeria. Colonial politics, ethnographical practices, theoretical developments. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Grenfell, M. ed. (2014). Pierre Bourdieu. Key Concepts. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hilgers, M. and Mangez, E. (eds.) Bourdieu’s Theory of Social Fields. Abingdon: Routledge.

Husserl, E., (1939|1973). Erfahrung und Urteil. Untersuchungen zur Genealogie der Logik. Hamburg: Claassen. Experience and Judgement. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

Macintyre, A. (1985). After Virtue. A study in moral theory. 2e. London: Duckworth.

Major, L. E. and Machin, S. (2018). Social mobility and its enemies. London: Pelican Books.

Mannheim, K. (1936). Ideology and Utopia, translated by Louis Wirth and Edward Shils. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Mannheim, K. (1940). Man and Society in an Age of Reconstruction, translated by Edward Shils. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Mansell, W. (2019). Ofsted plan to inspect ‘cultural capital’ in schools attacked as elitist, The Guardian September 3. [https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/sep/03/ofsted-plan-inspect-cultural-capital-schools-attacked-as-elitist. Retrieved June 25, 2020].

Martin, L. J. (2003). What is field theory? American Journal of Sociology 109.1: 1–49. [https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/375201. Retrieved July 22, 2020].

Maton, K. (2014) Habitus in M. Grenfell ed. (2014). Pierre Bourdieu. Key Concepts. Abingdon: Routledge. [The page numbering is from a epub edition).

Mauss, M. (1950 | 1966). Essai sur le don in sociologie et anthropologie (The Gift: forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France | London: Cohen and West.

Medvetz, T. and Sallaz, J. J. (2018). Pierre Bourdieu, a Twentieth-Century Life in Thomas Medvetz and Jeffrey J. Sallaz eds. The Oxford Handbook of Pierre Bourdieu. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199357192.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199357192-e-1. Retrieved September 23, 2019].

Moore, R. (2014). Capital in M. Grenfell ed. Pierre Bourdieu. Key Concepts. Abingdon: Routledge. [Page numbers are from the epub version).

The Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) (2019). School Inspection Handbook. Manchester: The Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills. [https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/814756/School_inspection_handbook_-_S5_4_July.pdf. Retrieved: July 22, 2020]

Parkin, F. (1979). Marxism and Class Theory. A bourgeois critique. London: Tavistock.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone. The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Putnam, R. D. (2015). Our Kids. The American Dream in crisis. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Reay, D. (2017). Miseducation. Inequality, education and the working class. Bristol: Policy Press.

Reckwitz, A. 2002 ‘Toward a theory of social practices: a development in culturalist theorizing’, European Journal of Social Theory 5(2): 243-63. [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/13684310222225432. Retrieved July 22, 2020].

Riding A. (2002). Pierre Bourdieu, 71, French Thinker and Globalization Critic, The New York Times. [https://www.nytimes.com/2002/01/25/world/pierre-bourdieu-71-french-thinker-and-globalization-critic.html. Retrieved September 28, 2019].

Ritzer, G (2003). Contemporary Sociological Theory and its Classical Roots: The Basics. New York; McGraw-Hill.

Robbins, D. (1990). The Work of Pierre Bourdieu: Recognising Society. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Robbins, D. (2014). Theory of practice in M. Grenfell ed. (2014). Pierre Bourdieu. Key Concepts. Abingdon: Routledge.

Ross, A. (2000). Curriculum. Construction and critique. London: Falmer Press.

Rushe, D. (2020). Making billions v making ends meet: how the pandemic has split the US economy in two, The Guardian August 15. [https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/aug/16/us-inequality-coronavirus-pandemic-unemployment. Retrieved: August 15, 2020].

Sachs, J. (2001). Aristotle: Ethics, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (https://www.iep.utm.edu/aris-eth/. Retrieved: July 19, 2020).

Sapiro, G. (2015). Habitus: History of a concept, International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioural Sciences 10: 484-9. Oxford: Elsevier.

Schambler, Graham (2015). Sociological Theorists: Pierre Bourdieu. [http://www.grahamscambler.com/sociological-theorists-pierre-bourdieu/. Retrieved: July 22, 2020].

Smith, M. K. (2001). ‘Kurt Lewin, groups, experiential learning and action research’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/kurt-lewin-groups-experiential-learning-and-action-research/. Retrieved: July 20, 2020].

Smith, M. K. (2015, 2020). What is education? A definition and discussion. The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/what-is-education-a-definition-and-discussion/. Retrieved: August 15, 2020].

Thatcher, J., Ingram, N., Burke, C. and Abrahams, J. eds. (2018). Bourdieu, The Next Generation- The Development of Bourdieu’s Intellectual Heritage in Contemporary UK Sociology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Thomson, P. (2014). Field in M. Grenfell ed. (2014). Pierre Bourdieu. Key Concepts. Abingdon: Routledge.

Wacquant, L. J. D. (1989). Towards a Reflexive Sociology: A Workshop with Pierre Bourdieu, Sociological Theory 7. [https://loicwacquantorg.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/lw-1989-a-reflexive-sociology-a-workshop-with-pb.pdf. Retrieved July 17, 2020]

Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). Toward a Social Praxeology: The Structure and logic of Bourdieu’s Sociology in P. Bourdieu and L. J. D. Wacquant An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Wacquant, L. J. D. (2004). Following Bourdieu into the Field. Ethnography 5(4): 387–414.

Warde, A. (2004). Practice and Field. Revisiting Bourdieusian concepts. CRIC Working Paper, Discussion Paper and Briefing Paper Series. Manchester: University of Manchester. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238096928_Practice_and_Field_Revising_Bourdieusian_Concepts. Retrieved: July 23, 2020]

Willis, P. E. (1977). Learning to Labour. How working class kids get working class jobs. Farnborough: Saxon House.

Acknowledgements: Photograph: PITR “Pierre Bourdieu” @ Parigi giugno 2010 by Strifu | flickr ccbyncsa2

© Mark K Smith 2020

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2020). Pierre Bourdieu on education: Habitus, capital, and field. Reproduction in the practice of education, the encyclopaedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/dir/pierre-bourdieu-habitus-capital-and-field-exploring-reproduction-in-the-practice-of-education. Retrieved: insert date].

updated: August 11, 2025